Table of Contents

- The Morning the Pacific Roared: March 11, 2011

- A Perfect Storm: The Cascadia Subduction Zone Explained

- The Earthquake That Shook More Than Japan

- Cascadia’s Sleeping Giant: Geological and Historical Context

- Early Warnings and the Challenge of Tsunami Prediction

- Tsunami Waves on the Oregon-Washington Coast: Arrival and Impact

- Communities on the Edge: Human Stories from the Coastline

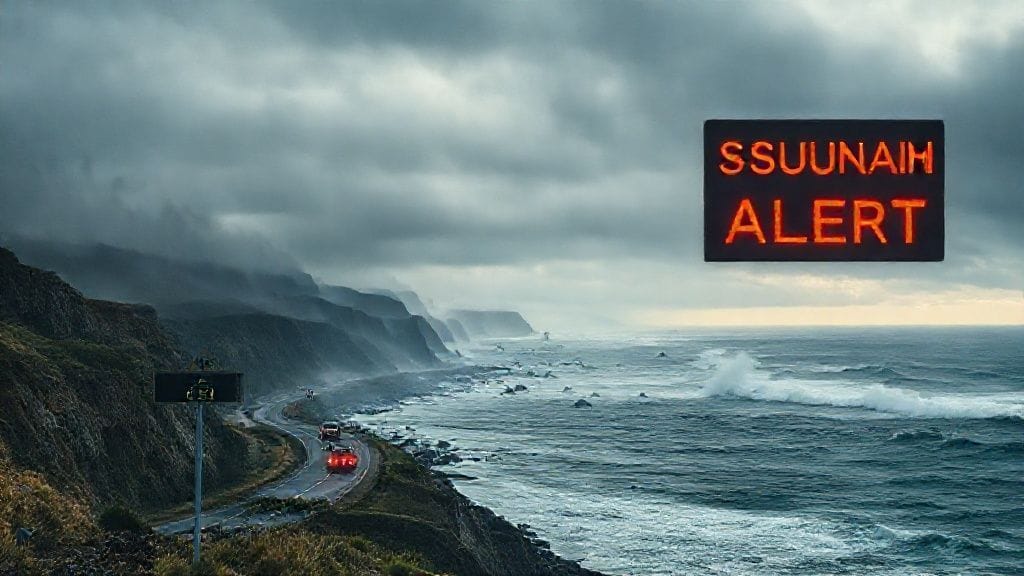

- Emergency Response and Evacuation Efforts

- Infrastructure Shaken: Ports, Roads, and Powerlines

- Environmental Consequences: The Changing Coastal Landscape

- Economic Fallout and Recovery Prospects

- The Role of Technology: Seismic Networks and Tsunami Buoys

- National and Regional Policy Reactions: Lessons Learned

- Comparing 2011 to Past Cascadia Events: A Historical Perspective

- The Psychological Toll: Fear and Resilience

- How 2011 Altered Our View of the Cascadia Threat

- The Science of Prediction: Progress and Limitations

- Coastal Communities Today: Preparedness and Vigilance

- Art, Memory, and Commemoration: The Event in Culture

- A Glimpse Into the Future: Preparing for the Next Big One

- Conclusion: The Pacific’s Reminder of Nature’s Raw Power

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- External Resource

- Internal Link

The Morning the Pacific Roared: March 11, 2011

At 5:46 PM local time in Japan, the Earth erupted with a force so tremendous it was barely conceivable. The 9.0 magnitude Tōhoku earthquake unleashed a tsunami that raced across the Pacific Ocean. While the world’s eyes were riveted on the devastation sweeping across Japan, thousands of miles away along the rugged Oregon and Washington coasts, the waves arrived with their own deadly message — a reminder that the Pacific Rim is a place where the Earth’s fury waits patiently beneath the surface.

In the minutes following the Japanese disaster, people in Oregon and Washington were startled by the sudden roar of approaching water. Along cliffs, beaches, and small towns, the tsunami waves, generated thousands of miles away, hammered shorelines with wave heights sometimes reaching several feet — smaller than Japan’s cataclysm, yet enough to flood harbors, capsize boats, and disrupt lives. For many in these coastal communities, it was a moment of reckoning with a geologic threat that had long lurked in silence.

But this tsunami was more than just an echo from Japan. It served as a painful preview of what could happen if the Cascadia Subduction Zone — a massive fault line just offshore — ruptured nearby. This was Nature’s clarion call, an invitation to confront history, geology, and future risk with vigilance and resolve.

A Perfect Storm: The Cascadia Subduction Zone Explained

Beneath the turbulent waters of the Pacific Northwest lies a tectonic boundary known as the Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ). This mysterious seam between the Juan de Fuca plate and the North American plate stretches roughly 1,000 kilometers from Northern California through Oregon and Washington, into southern British Columbia. Over centuries, the oceanic plate slowly slides underneath the continental plate, accumulating stress until it suddenly snaps, triggering massive earthquakes and tsunamis.

Scientists have long understood that this subduction zone poses one of the greatest seismic threats in North America. Its last great rupture, roughly 317 years ago, unleashed an estimated magnitude 9.0 earthquake and tsunami that reshaped coastlines and claimed untold lives among Indigenous communities — a story passed down through oral tradition.

Yet the scale of destruction Japan faced in 2011 struck a profound chord with experts and residents alike. Could Cascadia unleash an earthquake just as devastating, or worse? The tsunami that reached the Oregon and Washington coasts that day was a powerful wake-up call.

The Earthquake That Shook More Than Japan

While Japan bore the brunt of the Tōhoku quake and resultant tsunami, seismic waves propagated through the Earth, registering worldwide. For the Pacific Northwest, the arrival of the tsunami was a stark reminder of shared danger. The tsunami’s journey — spanning nearly 8,000 kilometers — took less than 10 hours to reach the US West Coast.

Oregon and Washington, both equipped with tsunami warning systems, had mere minutes to react. The National Weather Service, in coordination with the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center, alerted local emergency managers, prompting evacuations and the closure of vulnerable ports and marinas. Despite these efforts, the waves inundated low-lying areas, flooding marinas, destroying docks, and damaging critical infrastructure.

The event was a vivid demonstration that in an interconnected geological system like the Pacific Rim, immense events in one place can reverberate across the ocean, with real consequences far from the epicenter.

Cascadia’s Sleeping Giant: Geological and Historical Context

The Cascadia fault is a geological paradox — an interval of relative quiet punctuated by cataclysmic release. For centuries, the subduction zone has been “locked,” with the oceanic plate pushing against the continent. This locked scenario results in the gradual deformation of the crust and enormous buildup of strain energy.

In 1700, on the night of January 26, the last Cascadia megathrust earthquake sent tsunami waves crashing into the western coastline of the Pacific Northwest and caused ground shaking that was felt for hundreds of miles. Indigenous oral histories — stories of “earth shook, and water came up the river” — corroborated geological evidence, as did Japanese records of an “orphan tsunami” striking from unknown origins.

Since then, science has pieced together the rhythm of Cascadia’s giant quakes, estimating a recurrence interval of roughly 300 to 600 years. But the threat remains ever-present, suspended like a ticking clock beneath the waves.

Early Warnings and the Challenge of Tsunami Prediction

One of the greatest difficulties faced on March 11, 2011 — and always in the Pacific Northwest — is the tiny window for warning when a local earthquake generates a tsunami. Unlike distant tsunamis that take hours to arrive, a local Cascadia event would send waves pounding ashore within 15 to 30 minutes, leaving precious little time to evacuate.

The Japanese disaster, initiated far away, offered valuable time for warnings to spread along the North American coast. But it also underscored the urgent necessity to improve real-time seismic monitoring and public education.

Since then, Oregon, Washington, and neighboring British Columbia have invested heavily in early warning systems, integrating seismic detection, real-time communications, and community drills to make sure people understand the cliffhanger scenario they face.

Tsunami Waves on the Oregon-Washington Coast: Arrival and Impact

When the tsunami waves hit the Oregon and Washington shores on March 11, they brought a mixture of calm and chaos. At most beaches, waves measured between 3 to 6 feet, sufficient to flood docks, overturn boats, and drag debris into harbors. In some places, particularly where the shoreline funnels and concentrates wave energy — such as around bays and estuaries — waves were even higher.

Portland and Seattle, inland and shielded by natural features, escaped direct impact, but coastal towns like Newport, Seaside, and Long Beach confronted the force head-on.

At Newport’s harbor, incoming waters surged unpredictably, flooding the docks and forcing fishermen to scramble. Marina owners counted damaged vessels as floating debris drifted ashore. In Washington’s Long Beach Peninsula, the coastline’s intricate geography focused waves into narrow channels, exacerbating flooding and damage. Emergency sirens wailed, evacuations ensued, and residents grappled with the shock of nature’s raw power striking their doorstep.

Communities on the Edge: Human Stories from the Coastline

Behind every statistic are human lives etched with anxiety, courage, and resilience. For coastal residents, tsunami warnings sparked a surge of adrenaline, confusion, and at times, fear.

Mary Larson, a longtime fisherman in Seaside, recounted with a shiver how she and her neighbors evacuated uphill after sirens sounded. “We’ve always known it could happen, but until that day, it was just a story,” she reflected. “Hearing the ocean roar and seeing those waves come in, it hit home hard.”

Some chose to stay and secure property, a risky gamble against what was, relatively speaking, a small tsunami. For emergency workers, the day was a crucible — testing preparedness plans and community bonds.

Stories emerged of neighbors helping strangers uphill, families reunited after frantic searches, and first responders braving uncertain conditions to keep people safe. It was a tapestry woven from fear and solidarity.

Emergency Response and Evacuation Efforts

March 11 also demonstrated the strength — and limits — of regional emergency response. Local officials had drilled for years on tsunami evacuation protocols, and their swift actions undoubtedly saved many lives.

The Oregon Office of Emergency Management and Washington’s Emergency Management Division disseminated alerts quickly, in coordination with federal agencies. Coastal sirens sounded, schools and businesses closed, and evacuation routes filled with residents moving to higher ground.

Yet for some rural or isolated communities, the rapid arrival of the waves made evacuation thrillingly tight. The event stressed the importance of community preparedness, redundancy in communication, and the vital role of individual responsibility.

Infrastructure Shaken: Ports, Roads, and Powerlines

Though the tsunami was much less destructive than Japan’s, critical infrastructure suffered notable setbacks. Floodwaters submerged parts of coastal highways, washed out portions of Oregon’s Highway 101, and inundated port facilities.

Boats moored in harbors experienced damage from turbulent waters, leading to significant economic challenges for commercial fisheries. Several marinas required costly repairs or reconstruction. Powerlines near the shore were sometimes compromised, leading to outages.

These disruptions underscored how vulnerable coastal infrastructure is to sudden natural disasters, sparking conversations about building resilience and reinforcing assets against future tsunamis.

Environmental Consequences: The Changing Coastal Landscape

Beyond immediate human impacts, the tsunami triggered subtle but important environmental shifts. Saltwater inundation affected estuarine ecosystems, with tidal flats and marshlands temporarily flooded and breeding grounds for fish and birds disturbed.

Sediment deposits moved by wave energy altered beaches and underwater topography. Local scientists noted shifts in algal blooms and changes in water chemistry in some bays.

This natural “stirring” carries implications for fisheries, wildlife habitats, and recreation. It also reminds us that geological events ripple through the living fabric of the coast, beyond buildings and roads.

Economic Fallout and Recovery Prospects

Economically, the tsunami’s impact was a shock to local communities whose livelihoods depend heavily on fishing, tourism, and maritime industries.

The fishing fleet faced repairs and lost days at sea, while tourist-dependent businesses had to close temporarily or weather cancellations. However, because the damage was relatively contained, recovery was swift compared to other disasters, helped in part by state and federal aid.

Yet the event produced a sober assessment of vulnerabilities — prompting investment in infrastructure upgrades, early warning systems, and community education to safeguard economic futures against “the big one” yet to come.

The Role of Technology: Seismic Networks and Tsunami Buoys

By 2011, an array of advanced technologies was working silently to detect and track seismic events and tsunami waves. Coastal seismic stations and the DART (Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis) buoys collect real-time data critical to issuing warnings.

On this day, these systems lived up to their promise. Tsunami detection buoys alerted the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC), giving emergency agencies precious minutes. Yet the event also highlighted gaps — particularly in the speed and reach of communications to remote communities.

As a result, technological investments accelerated post-2011, pushing for more robust, redundant, and community-friendly systems.

National and Regional Policy Reactions: Lessons Learned

In the tsunami’s aftermath, policymakers at federal, state, and local levels took stock. Reports detailed the effectiveness of warning systems and emergency protocols while identifying areas for improvement.

Funding for the National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program increased. Oregon and Washington legislatures passed enhancements to building codes, land-use planning, and public education programs. The event also intensified cross-border collaboration with Canadian authorities.

At each level, the message was clear: the Pacific Northwest’s geological destiny demands proactive, science-driven governance.

Comparing 2011 to Past Cascadia Events: A Historical Perspective

While the 2011 tsunami’s energy was imported from Japan’s seismic catastrophe, it offered a tangible window into what a nearby Cascadia megathrust event might look like.

Historical reconstructions of the 1700 earthquake reveal shaking up to magnitude 9, with tsunamis tens of meters high in some places — dwarfing 2011’s modest waves on NW shores.

The comparison fuels a mix of dread and determination among scientists and communities. Preparing for the future means learning from history and the present — blending geology, engineering, and human experience.

The Psychological Toll: Fear and Resilience

It’s impossible to measure the earthquake and tsunami only in physical terms. The psychological imprint on residents along the coast was lasting. Many grappled with anxiety over future events, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and uncertainty about safety.

Yet human resilience shone through. Community drills increased, neighbors checked on each other, and emergency preparedness became part of everyday culture. Schools integrated disaster education, and local leaders nurtured a spirit of readiness balanced with hope.

This emotional landscape is as vital to study as any scientific data, because it shapes how societies face and endure disaster.

How 2011 Altered Our View of the Cascadia Threat

The tsunami’s arrival was a clarion call that raised public awareness to new heights. Before 2011, many residents were only vaguely familiar with the Cascadia threat; afterward, it became a topic of urgent conversation.

Media coverage, educational campaigns, and community engagement surged. More people saw the Pacific not just as a place of beauty, but also of profound geological dynamism and peril.

This shift inspired investment and activism — from state governments to grassroots organizations committed to saving lives and preserving communities.

The Science of Prediction: Progress and Limitations

Despite advances, predicting exactly when Cascadia will rupture remains impossible. Scientists rely on geologic records, GPS measurements, and seismic monitoring to assess probabilities, but timing remains a mystery.

The 2011 tsunami highlighted the importance of scenario planning and uncertainty management, teaching a vital lesson: readiness is the best tool we have.

Since then, research into early warning systems, paleo-seismology, and tsunami modeling has advanced substantially — though the specter of the “next big one” still looms.

Coastal Communities Today: Preparedness and Vigilance

Today, Oregon and Washington’s coastal populations have embraced preparedness as a way of life. Public education, evacuation drills, and infrastructure fortification are regular themes.

Community tsunami sirens, clearly marked evacuation routes, and multi-lingual awareness materials are commonplace. Integrating Indigenous knowledge with modern science enriches understanding and foster resilience.

Still, maintaining vigilance is an ongoing challenge as populations grow and climate change introduces new complexities.

Art, Memory, and Commemoration: The Event in Culture

The 2011 tsunami’s impact resonates beyond science and emergency response. It has inspired artists, writers, and performers along the Pacific Northwest coast to explore themes of loss, survival, and connection to the natural world.

Murals depict the ocean’s wrath and hope; community events commemorate survival and honor ancestors who faced past shocks.

These cultural expressions keep memory alive, transforming trauma into collective identity and strength.

A Glimpse Into the Future: Preparing for the Next Big One

The Pacific Northwest stands at a crossroads. If Cascadia’s subduction zone ruptures tomorrow, it will dwarf the 2011 event in scope and devastation.

Yet with hard-won knowledge and community resolve, there is hope.

Ongoing investments in early warning networks, resilient infrastructure, and public awareness programs provide a foundation. Every drill and conversation is a brick in a bulwark against devastation.

The ocean’s roar on March 11, 2011 was a wake-up call — humanity’s invitation to respect and prepare for the raw power slumbering beneath the surface.

Conclusion

March 11, 2011, will forever be etched in memory as the day the Pacific Ocean reminded the Oregon and Washington coasts of its incredible might. Born from a distant earthquake in Japan, the resultant tsunami was more than a mere ripple across the sea. It was a powerful herald of a geological future cloaked in uncertainty but illuminated by science and human courage.

This event stitched together the lives of people and places around the Pacific Rim into a tapestry of shared vulnerability and shared resilience. For the communities along the Oregon and Washington shorelines, the lesson was clear: the Pacific is at once a source of life and deep existential challenge.

Yet, as we look to the horizon, we find comfort in the relentless human spirit — one that learns, adapts, and prepares for whatever the Earth’s deep heart may send. The road ahead demands vigilance, compassion, and unity, but also the quiet confidence that we are, at last, listening.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly caused the tsunami that affected Oregon and Washington in 2011?

A1: The tsunami waves that reached the Oregon and Washington coasts originated from the massive 9.0 magnitude earthquake off the coast of Japan (the Tōhoku earthquake). The seismic energy displaced large volumes of water, sending waves across the Pacific Ocean.

Q2: Why did the tsunami waves affect the Pacific Northwest if the earthquake happened near Japan?

A2: Tsunamis travel at high speeds across the ocean. The Pacific acts as a giant basin transmitting these waves. Though the waves lose some energy en route, they can still cause flooding in distant places like the Oregon and Washington coasts.

Q3: How dangerous was the tsunami compared to a potential Cascadia Subduction Zone event?

A3: The 2011 tsunami was relatively small along the Northwest coast compared to what would likely occur if the Cascadia Subduction Zone ruptured nearby. A Cascadia megathrust event could produce much larger, more destructive tsunamis and shaking closer to home.

Q4: How prepared were Oregon and Washington for the tsunami in 2011?

A4: Both states had tsunami warning systems and evacuation plans in place, which were activated effectively. However, the event highlighted areas for improvement, especially in communication and reaching remote communities on short notice.

Q5: How is the threat from the Cascadia Subduction Zone being monitored today?

A5: Scientists use seismic networks, GPS measurements, tsunami detection buoys, and geological research to monitor Cascadia. Ongoing efforts focus on improving early warning times and public preparedness.

Q6: What steps have coastal communities taken to prepare for future tsunamis?

A6: Many coastal towns have developed evacuation plans, installed warning sirens, educate residents and tourists, and worked to harden infrastructure. Community drills and public awareness campaigns are increasingly common.

Q7: What was the human impact of the tsunami on Oregon and Washington?

A7: Although there were no fatalities, property damage, flooding, and emotional trauma affected many communities. It motivated stronger cohesion and commitment to disaster readiness.

Q8: How does this event fit into the larger history of Pacific Northwest seismic activity?

A8: It was a reminder of the constant danger posed by the Cascadia Subduction Zone and other faults. The Pacific Northwest has a documented history of powerful earthquakes and tsunamis, the last major one occurring in 1700.