Table of Contents

- A Flash of Light: The Night the Laser Was Born

- Setting the Stage: Mid-20th Century America and the Race for Innovation

- The Spark of Genius: Theodore Maiman’s Early Life and Inspirations

- From Theory to Reality: The Science Behind the Laser

- The Laboratory Crucible: Hughes Research Laboratories, 1960

- May 16, 1960: A Historic Moment in Physics

- The First Laser Pulse: A Triumph of Persistence and Precision

- The Immediate Reaction: Awe, Skepticism, and Scientific Wonder

- The Laser’s Early Applications: From Science Fiction to Practical Tools

- The Arms Race and Lasers: Cold War Imperatives for Innovation

- Commercializing Light: The Laser Enters Industry and Medicine

- Cultural Ripples: Lasers in Popular Imagination and Media

- Scientific Rivalries and Collaborations Around the Laser

- Expanding Horizons: How Laser Technology Shaped Future Research

- The Legacy of 1960: Lasers and the Dawn of the Photonic Age

- Key Figures Beyond Maiman: Other Pioneers in Laser Development

- Ethical Reflections: Power, Danger, and Responsibility in Laser Use

- The Laser in the Global Context: From California to the World

- Stories from the Lab: Anecdotes of Failure, Hope, and Breakthrough

- The Evolution of the Laser: From Ruby to Fiber and Beyond

- Around the World: International Responses and Adaptations

- Modern Lasers: The Pulse of Today’s Technology and Innovation

- Remembering May 16: Commemoration and Historical Memory

- The Future of Laser: Endless Possibilities Illuminated

- Conclusion: Light That Forever Changed the World

A Flash of Light: The Night the Laser Was Born

It was an ordinary evening in early spring in 1960 at the Hughes Research Laboratories in California. Yet inside that unassuming lab, a series of events unfolded that would irrevocably change the trajectory of science and technology. A crimson pulse of coherent light—the world’s first laser—flared to life for one fleeting instant, embodying decades of theoretical triumph and practical endurance. The air was thick with anticipation, the hum of machines intertwining with the hopes of a young physicist named Theodore Maiman. That brief beam of light, just a few millimeters across and lasting less than a second, was a quiet yet revolutionary whisper heard reverberating through the halls of history.

The invention of the laser was not just an isolated moment of brilliance but the culmination of a century’s worth of exploration into the nature of light, matter, and energy. It emerged as the embodiment of human curiosity and ingenuity, a beacon heralding the dawn of the photonic age. But to truly grasp the importance and the drama of that May evening in California, one must delve into the intertwining stories of people, science, and the intense geopolitical context that motivated such a breakthrough.

Setting the Stage: Mid-20th Century America and the Race for Innovation

The 1950s and 1960s in the United States were times of extraordinary scientific excitement and political tension. The cold war shaped much of American technological ambition, as the quest for supremacy in nuclear arms, space, and communication accelerated. The government and private sector poured resources into laboratories and universities that became veins pulsing with innovation.

This era also witnessed remarkable advances in physics — quantum theory was no longer an abstract field but began to suggest practical applications. The maser, an invention that amplified microwaves instead of light, had already been demonstrated by Charles Townes and Arthur Schawlow. Their work ignited a race to transform the maser concept into something more tangible: a device that could harness light itself.

California, with its sun-drenched labs and growing aerospace industry, became a hotbed for cutting-edge research. It was here, against the backdrop of Cold War anxieties and a belief in scientific progress as a form of national defense and prosperity, that the stage was set for the laser to emerge.

The Spark of Genius: Theodore Maiman’s Early Life and Inspirations

Before May 16, 1960, Theodore Harold Maiman was little known outside scientific circles. Born in 1927 in Los Angeles, Maiman demonstrated early an insatiable curiosity and a knack for engineering. After serving in the U.S. Navy and earning degrees in engineering and physics, he joined Hughes Aircraft Company, a private contractor with the resources and vision to push the boundaries of technology.

Maiman was both a brilliant experimentalist and a careful theorist. He was fascinated by the promise of the laser—not just as a scientific curiosity but as a practical device capable of revolutionizing multiple industries. While many scientists were skeptical about the feasibility of a laser, Maiman’s confidence and meticulous approach distinguished him.

His choice of a synthetic ruby crystal as the lasing medium was unconventional. Whereas others had proposed gas or other materials, Maiman believed the solid-state ruby offered a convenient and effective route to achieve stimulated emission—the fundamental principle behind laser operation. This decision would prove decisive.

From Theory to Reality: The Science Behind the Laser

The term “laser” itself is an acronym: Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. It builds on the quantum mechanical idea that atoms, energized by an external source (pumping), can emit photons coherently and in phase, resulting in a concentrated beam of monochromatic light.

The principle was theorized by Albert Einstein as early as 1917, but practical implementation was elusive for decades. The discovery of the maser gave hope. However, moving from microwave emission to visible light posed immense challenges—materials science, energy sources, engineering precision, and optical design had to come together perfectly.

Maiman’s ruby laser operated by exciting chromium ions within the synthetic ruby crystal using intense flashes of light from a xenon flash lamp. The chromium ions, upon relaxation, emitted photons that bounced between mirrors at each end of the rod, stimulating further emission and ultimately producing the first coherent laser beam.

The Laboratory Crucible: Hughes Research Laboratories, 1960

Hughes Aircraft Company was a powerhouse of research—steeped in secrecy, brilliance, and competition. The laboratories in Malibu, California, were staffed by some of the sharpest minds drawn by the possibility of groundbreaking discoveries.

Within this charged environment, Maiman worked tirelessly, often facing skepticism and limited support. Funding was a challenge, as the laser’s feasibility was questioned. Yet, armed with technical skill and a fierce determination, Maiman assembled his apparatus piece by piece. The ruby rod, precision mirrors, flash lamps, and the puzzling alignment of optical components demanded almost surgical attention.

Despite setbacks and failed attempts, the team’s morale was buoyed by the burgeoning promise. “If it works, everything changes,” Maiman is reported to have said.

May 16, 1960: A Historic Moment in Physics

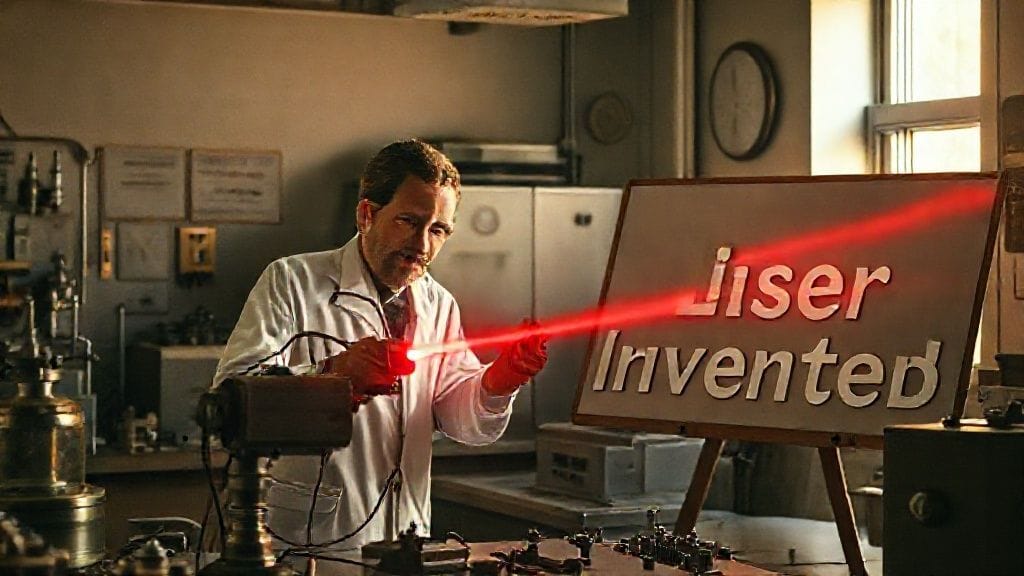

On the day itself, the air inside the laboratory was dense with expectation and quiet apprehension. Maiman and his colleagues prepared the apparatus and activated the xenon flash lamp. When the first pulse of coherent red light was emitted—a brief, brilliant burst—time seemed to pause.

This was not just a scientific milestone, but a moment heavy with symbolic power—a human-made light springing from understanding the quantum nature of atoms. The “light amplification” was no longer a theory; it was a palpable, radiant truth.

Maiman’s concise announcement to his supervisors, “We have a laser,” marked the beginning of a new era.

The First Laser Pulse: A Triumph of Persistence and Precision

That inaugural light pulse was fragile—lasting less than a thousandth of a second—but represented the successful confluence of theory, engineering, and experimental skill. It signified mastery over light’s elusive properties.

Maiman’s laser beam had a wavelength of 694.3 nanometers, producing a deep crimson glow. Unlike the diffuse nature of incandescent light, this beam was narrow, monochromatic, and remarkably coherent—qualities essential for myriad technological uses.

The physical construction—a few pounds of meticulously arranged parts—belied the infinite possibilities contained within that tiny flash of light.

The Immediate Reaction: Awe, Skepticism, and Scientific Wonder

News of the ‘laser invented’ moment soon spread through scientific circles. The initial reaction was a mixture of astonishment and disbelief. Some physicists greeted it as the fulfillment of long-standing predictions; others questioned the durability and practicality of the device.

Media coverage was reserved at first, though the term “laser” quickly captured public imagination. Its name alone conjured images of the future, of precision tools and otherworldly beams.

Yet the scientific community embraced this breakthrough as a door to unexplored possibilities. Conferences buzzed with theories on laser applications—communications, medicine, manufacturing, even warfare.

The Laser’s Early Applications: From Science Fiction to Practical Tools

Within a few short years, laser technology transitioned from laboratory curiosity to practical tool. Early adopters included telecommunications companies, which envisioned lasers as replacements for bulky and unreliable signal amplifiers.

In medicine, lasers promised less invasive surgical techniques, with enhanced precision and reduced recovery times. One of the first successful applications was in ophthalmology, correcting vision with unprecedented accuracy.

In industry, lasers were used for cutting and welding materials with finer control than ever before. Even in scientific research, lasers became indispensable tools—from spectroscopy to quantum physics experiments.

But what is striking is how swiftly the laser moved from speculative technology to tangible impact, transforming diverse fields across the globe.

The Arms Race and Lasers: Cold War Imperatives for Innovation

It would be naïve to separate the laser’s evolution from Cold War dynamics. Superpowers quickly recognized potential military applications—ranging from missile defense systems to targeting devices.

Government agencies poured funds into laser research, seeking strategic advantage. The possibility of “death rays” and space weapons became not just science fiction but strategic considerations.

This urgency accelerated developments but also raised ethical concerns about the use of such advanced technology for destructive purposes.

Commercializing Light: The Laser Enters Industry and Medicine

By the late 1960s and 1970s, laser technology had matured sufficiently to spawn a growing range of commercial products. Companies invested in the development of laser printers, barcode scanners, and optical disc readers.

The laser’s unparalleled precision improved manufacturing in electronics and automotive industries. Medical procedures proliferated, while telecommunications benefited from laser-based fiber optics, enabling long-distance data transmission and eventually fueling the internet revolution.

The story of the laser’s invention thus became intertwined with the story of modern technology and everyday life.

Cultural Ripples: Lasers in Popular Imagination and Media

Lasers soon etched themselves into the fabric of popular culture—movies, literature, and television took inspiration from the sleek beams and futuristic potential.

From James Bond’s iconic “laser grid” to Star Wars’ “blaster bolts,” the laser became a symbol of the cutting edge, of power and mystery. It represented the pinnacle of human achievement but also a harbinger of a new technological order.

Interestingly, this cultural fascination often preceded full technological understanding, fueling public fascination and scientific curiosity alike.

Scientific Rivalries and Collaborations Around the Laser

The story of laser invention was not a solitary one. Alongside Maiman, numerous scientists worldwide raced toward similar achievements. Rivalries sharpened competition; collaborations broadened horizons.

While Maiman built the first visible light laser, others pursued gas lasers, semiconductor lasers, and new materials. These efforts sometimes overlapped, competed, or complemented each other.

Intellectual property disputes and patent battles ensued, reflecting the immense economic and strategic stakes associated with laser technology.

Expanding Horizons: How Laser Technology Shaped Future Research

The laser’s invention set off a chain reaction across many research fields. It enabled precision measurements of fundamental constants, tests of quantum electrodynamics, and the exploration of condensed matter physics.

Lasers facilitated unprecedented control over matter at the atomic scale, paving the way for fields such as nanotechnology and optical computing.

More recently, ultrafast lasers have allowed scientists to observe molecular processes in real time, deepening our understanding of chemistry and biology.

The Legacy of 1960: Lasers and the Dawn of the Photonic Age

Maiman’s invention on May 16, 1960, is not just a historical date but the point at which humanity truly began to harness the power of light beyond illumination. The laser inaugurated the photonic age—a new epoch where information, energy, and even matter itself could be manipulated by photons as adeptly as classical electronics controlled electrons.

Economies transformed, industries evolved, and sciences advanced rapidly. The ripple effect of that first pulse is felt in the smartphones we use, the surgeries we trust, and the networks connecting our world.

Key Figures Beyond Maiman: Other Pioneers in Laser Development

Although Theodore Maiman’s name is inscribed in history as the laser’s inventor, many others contributed foundational work. Charles Townes and Arthur Schawlow’s theoretical framework underpinned the laser’s design. Nikolay Basov and Alexander Prokhorov in the Soviet Union independently developed maser and laser theories, earning Nobel Prizes.

This collective endeavor highlights the international and collaborative nature of scientific progress.

Ethical Reflections: Power, Danger, and Responsibility in Laser Use

Beyond its technological marvel, the laser also raised profound ethical questions. Its potential use in weapons systems, privacy intrusions, and environmental impacts prompted reflection.

Scientists and policymakers grappled with balancing innovation’s benefits against risks. This dialogue continues to this day as laser technology expands into new realms.

The Laser in the Global Context: From California to the World

The invention of the laser in a Malibu lab was a moment of global significance. Scientific communities worldwide adopted and adapted laser technology, integrating it into diverse cultures and economies.

International collaborations flourished, and laser research laboratories sprouted across continents, illustrating how a local breakthrough transcended borders to enrich humanity universally.

Stories from the Lab: Anecdotes of Failure, Hope, and Breakthrough

Behind the polished scientific narrative lie stories of frustration—failed experiments, equipment breakdowns, moments of doubt. Maiman himself faced skepticism and resource constraints. Yet his persistence paid off.

These human moments remind us that scientific progress is as much about character and resolve as about equations and apparatus.

The Evolution of the Laser: From Ruby to Fiber and Beyond

From the crimson ruby laser, development raced forward—helium-neon lasers producing stable red light, semiconductor diode lasers shrinking devices to microscopic scale, and fiber lasers enabling powerful, flexible beams.

Each innovation expanded the laser’s applications and integration into society.

Around the World: International Responses and Adaptations

The Soviet Union, Japan, Europe, and others rapidly embraced laser technology for industry, medicine, and defense. Their approaches reflected differing scientific cultures and priorities, enriching the global innovation tapestry.

Modern Lasers: The Pulse of Today’s Technology and Innovation

Today, laser technology pulses at the core of countless advanced technologies—3D printing, autonomous vehicles, medical diagnostics, telecommunications, and quantum computing.

Its evolution continues, propelled by new materials, artificial intelligence integration, and ever-expanding human ambition.

Remembering May 16: Commemoration and Historical Memory

May 16, 1960, is celebrated in scientific history as the birth of an era. Institutions, museums, and scholars commemorate the laser’s invention as a defining human achievement, inspiring future generations.

The Future of Laser: Endless Possibilities Illuminated

What lies ahead for the laser? Prospects include fusion energy through laser ignition, ultra-precise space communication, revolutionary medical therapies, and potential breakthroughs in quantum information.

The path is as luminous as the beam of light first emitted sixty years ago.

Conclusion

The story of the laser's invention is a testament to human curiosity, determination, and ingenuity. That modest crimson pulse, fleeting and fragile, illuminated not only a laboratory in Malibu but the path toward a future transformed by light itself. From theoretical abstractions to practical marvels, the laser symbolizes the profound power of science to reshape realities and expand horizons. As we look ahead, we are reminded that even the smallest, most precise flash of insight can change the world forever—lighting the way for generations to come.

FAQs

1. What exactly was invented on May 16, 1960?

On this day, Theodore Maiman successfully operated the first functioning laser, producing a pulsed beam of coherent red light from a synthetic ruby rod, marking the first practical realization of laser technology.

2. Why was the laser such a significant invention?

The laser represented a new source of light with unprecedented qualities—monochromaticity, coherence, and directionality—enabling numerous applications across science, medicine, industry, and communication.

3. Who were the key contributors to the development of the laser?

While Theodore Maiman invented the first working laser, foundational theoretical work by Charles Townes, Arthur Schawlow, Nikolay Basov, and Alexander Prokhorov was critical, along with many others advancing the related technologies.

4. What were the first practical applications of lasers?

Early lasers were used in spectroscopy, communications, medical surgeries (such as eye operations), and precision manufacturing processes.

5. How did the Cold War influence laser development?

The Cold War heightened the urgency for technological superiority, resulting in increased funding and interest in advanced weapons, communications, and defense applications involving laser technology.

6. Has the laser invention impacted everyday life?

Absolutely; lasers are at the heart of fiber-optic communications, barcode scanners, laser printers, medical equipment, and even entertainment devices like laser shows.

7. What materials did Maiman use for his laser?

Maiman's laser used a synthetic ruby crystal doped with chromium ions as the lasing medium, pumped by a xenon flash lamp.

8. How is the laser remembered today?

The laser’s invention is celebrated as one of the pivotal scientific achievements of the 20th century, symbolizing human capacity to convert abstract ideas into transformative technologies.