Table of Contents

- From Nara to Heian‑kyō: A Kingdom on the Move

- The Sacred Landscape of Early Japan

- Nara’s Splendor and the Shadow of the Monasteries

- Court Intrigues and the Longing for Escape

- Kammu’s Vision: Choosing the Site of Heian‑kyō

- Designing a New Imperial City

- 794: The Procession into Heian‑kyō

- Rituals, Omens, and the Spiritual Foundations of the New Capital

- Life in Early Heian‑kyō: Streets, Markets, and Mansions

- Reordering Power: Aristocrats, Monks, and the Emperor

- Women, Letters, and the Birth of a Courtly Culture

- From Political Center to Cultural Icon: The Making of Heian Japan

- The Hidden Costs: Peasants, Soldiers, and Peripheral Provinces

- Heian‑kyō Under Threat: Rebellions, Disease, and Fire

- The Long Echo: From Heian‑kyō to Kyoto and Modern Memory

- Historians’ Debates: Why the Capital Move Mattered

- Conclusion

- FAQs

- External Resource

- Internal Link

Article Summary: In the year 794, when the capital of Japan moved to Heian‑kyō under Emperor Kammu, it marked not just a change of address but a profound reordering of power, belief, and everyday life across the archipelago. This article follows the story from the sacred landscapes of early Japan and the Buddhist-dominated court of Nara to the carefully chosen river basin that would become Heian‑kyō. It explores why the capital of japan moved, how geomancy, politics, and fear of monastic power combined to drive the decision, and what it meant for aristocrats, monks, soldiers, and peasants alike. Through narrative reconstructions of the great procession of 794, the planning of the new grid city, and the flowering of courtly letters and poetry, we see how a political maneuver became the cradle of classical Japanese culture. Yet behind the elegance of the Heian age lay heavy burdens: forced labor, harsh provincial realities, and recurring disasters that tested the city’s endurance. Historians still debate whether the move truly freed the throne from religious domination or merely shifted the balance among aristocratic clans. By tracing these tensions across centuries, the article shows how the day the capital of japan moved to Heian‑kyō continues to echo in Kyoto’s streets, shrines, and in Japan’s collective memory today.

From Nara to Heian‑kyō: A Kingdom on the Move

When the capital of Japan moved to Heian‑kyō in 794, the sound that first announced the change was not the scratch of a brush on imperial edicts, but the creak of carriage axles, the clop of oxen’s hooves, and the low murmur of thousands of people abandoning a city. The air between Nara’s temple roofs and the wooded hills trembled with departure. Courtiers in layered silks watched their own mansions disassembled beam by beam, lacquer chests loaded onto carts, family shrines tenderly packed away. Monks in great monasteries, who had grown accustomed to summoning emperors with scripture and ritual, gazed after the receding procession and understood, with a stab of apprehension, that the world they had dominated for nearly a century was slipping southward.

The decision that the capital of japan moved from Nara to Heian‑kyō was the climax of decades of anxiety. Official proclamations spoke of auspicious omens and the need for a righteous, well-situated capital. But behind the elegant calligraphy lay fears of political stagnation, divine displeasure, and the encroaching power of the Buddhist institutions that ringed Nara like a spiritual fortress. Emperor Kammu, the man who ordered the move, was not content to reign in the shadow of those tiled roofs. He wanted light, air, and distance: distance from meddlesome monks, distance from ancestral curses thought to cling to certain places, and distance from the constraints of precedent.

It is astonishing, isn’t it, how a single decision to relocate the center of government radiated outward into every corner of Japanese life? When the capital of japan moved, it uprooted court families who traced their presence in Nara over generations, but it also pulled in labor from distant provinces, conscripted to build roads, halls, and walls in a muddy valley still more forest than city. It altered trade routes as caravans and boat traffic shifted from old arteries to new ones. It redrew maps in the minds of poets and pilgrims alike, who now calculated distance not from Nara’s pagodas but from the nascent palaces of Heian‑kyō.

Yet this was only the beginning. The city that rose from stakes and surveyors’ cords would become the stage for the flowering of Japan’s classical culture, later remembered simply as “Heian” culture—as if the age itself had fused with the city. The capital of japan moved once, but the mental geography of the nation would be permanently re-centered.

The Sacred Landscape of Early Japan

Long before any emperor dreamed of Heian‑kyō, the Japanese archipelago was a woven tapestry of sacred places. Mountains, rivers, and ancient trees were inhabited by kami—spirits whose moods could bring bountiful harvests or withering disaster. Power was as much about knowing how to speak to these unseen presences as it was about commanding men in armor. When the early Yamato rulers began to claim supremacy over rival clans, they did so not only with iron and horses, but through ritual: by presenting themselves as the intermediaries between people and the kami.

The idea of a “capital” in such a landscape was inherently spiritual. A permanent seat of rule was not just an administrative hub; it was a node where human order intersected with cosmic order. The capital had to be sited with care, attentive to mountains that could shield it, rivers that could nourish it, and the direction in which impure winds might blow. Before the capital of japan moved to Heian‑kyō, it had already moved several times in earlier centuries, often in response to death at court. The impurity associated with an emperor’s passing could cling to a palace, or even to a city, making continued residence there spiritually dangerous. Capitals had the fluidity of tents circling a sacred fire.

By the 8th century, however, a more settled pattern emerged. Influenced by Chinese models, Japanese rulers embraced the notion of a fixed, planned capital—a city whose layout echoed the cosmic order of the Tang dynasty’s great metropolises. Nara (Heijō‑kyō), established in 710, was the first enduring experiment, laid out in a strict grid, its imperial palace to the north, facing south like the palace at Chang’an. The city was not simply imposed on the land; it was attached to it through ritual, with ceremonies to pacify local deities, to recognize the power already present in the soil and rivers. To move a capital was to tear and restitch this sacred fabric.

Nara’s Splendor and the Shadow of the Monasteries

Nara dazzled contemporaries. Its avenues were broad, lined with tiled-roof residences, storehouses of grain, and offices for scribes. Envoys from the continent stepped ashore at Kyushu, traveled along government roads, and arrived to find not rustic chiefs but a city that spoke the language of empire. The colossal Great Buddha (Daibutsu) of Tōdai‑ji, cast in bronze and housed in a sprawling temple complex, embodied this ambition. When it was consecrated in 752, the ceremony drew priests from as far as India. The statue’s calm gaze, as tall as a multi-story house, seemed to proclaim that Nara was the spiritual and political pivot of Japan.

But Nara’s splendor had a price. The construction of its temples and palaces consumed enormous resources—timber cut from distant mountains, copper and gold smelted from difficult ores, rice tax collected from villagers whose backs bent in flooded fields. The government kept meticulous records of these flows, but as the 8th century wore on, those records began to reveal a troubling pattern: temples, once instruments of state power, were becoming power centers in their own right. Great monasteries like Tōdai‑ji and Kōfuku‑ji accumulated land and exemptions; monks could appeal directly to the court or, more ominously, threaten to call down divine wrath in the form of curses and rituals.

Court chronicles tell of monks who marched into the capital with portable shrines, carrying the living presence of a kami to the palace gates in protest. These were not quiet men in secluded cloisters; they were political actors, armed with sacred authority. Monks from powerful temples sometimes joined factional struggles, supporting one imperial prince over another, or backing ministers who favored their interests. Japanese historian Mikael Adolphson, in his study of medieval religious conflict, later described this phenomenon as the “temple‑shrine complex” gradually stepping into the same arena as warriors and courtiers (see Adolphson, The Teeth and Claws of the Buddha).

By the time Emperor Kammu came of age, this shadow over Nara was thickening. The very institutions that had helped legitimize imperial authority now seemed to threaten it. When the capital of japan moved, it would be in part an attempt to slip out from under this shadow.

Court Intrigues and the Longing for Escape

Inside Nara’s palaces, beyond the temple bells and market cries, a quieter but equally dangerous game unfolded. The imperial family was large: multiple consorts, numerous princes, and complex webs of maternal relatives. Behind each candidate for the throne stood one or more aristocratic clans, especially the powerful Fujiwara, who sought to bind the emperor to them through marriage and office. Intrigue was a constant hum in the background of daily life. A misplaced word, a failed alliance, or a rumor carefully whispered at the right moment could alter the succession.

Emperor Kammu, born in 737 as Prince Yamabe, did not have the purest lineage in the eyes of all his contemporaries. His mother was from a lower-ranked clan, and his ascent to the throne in 781 was not assumed from birth. Perhaps because of this, he was acutely aware of how fragile imperial authority could be. He had watched predecessors fall ill and die unexpectedly, seen accusations of sorcery and curses swirl around members of the court, and observed how swiftly monks stepped forward to interpret these misfortunes as signs of divine displeasure.

Several scandals in the late 8th century linked specific locations with spiritual pollution and political misfortune. When rebellions erupted in the remote northeast, when disease spread, when harvests faltered, many at court sought explanations not in taxation policies or military logistics, but in the unseen. A capital fixed in one place, no longer moving away from impurity after each imperial death, accumulated these fears like dust. The notion took root that Nara itself had become spiritually burdened—that its proximity to powerful temples, its long association with past crises, and its very stone foundations now weighed upon the throne.

So the longing for escape grew. The idea that the capital of japan moved was not born overnight; it gestated in private conversations, in confidential memorials from trusted advisors, in charts of geomancers and the whispered calculations of those who dared to imagine a different future. Kammu, once he donned the imperial robes, listened carefully. He would not be the first ruler to move a capital, but he intended to be the one who did it decisively, reshaping the political landscape as thoroughly as the physical one.

Kammu’s Vision: Choosing the Site of Heian‑kyō

Long before the first stake was driven into the soil of the Yamashiro basin, there were journeys. Kammu dispatched surveyors and officials to scout potential sites. They measured distances, observed river flows, and consulted local shrines to judge the disposition of the land’s kami. A capital could not simply be convenient; it had to be righteous. Early on, Kammu tried moving the capital to Nagaoka in 784, but the project was beset by disasters: flooding, political scandal, and the suspicious death of a key official, Fujiwara no Tanetsugu, who had been instrumental in choosing the site. Rumors of curses and foul play swirled together until the place itself seemed tainted.

Turning away from Nagaoka, Kammu fixed his eyes on a different valley, slightly further northeast. Nestled between the gentle mountains of the Higashiyama and Kitayama ranges, watered by the Kamo River and its tributaries, this basin had been home to small communities and local shrines for centuries. The rivers promised transport and irrigation, but not the catastrophic flooding that had darkened Nagaoka’s prospects. The encircling hills offered both protection and auspicious form; geomancers could readily align their compasses with its contours.

According to later chronicles, Kammu personally toured the region, standing where the future palace would rise, looking southward across fields and woods that, in his mind’s eye, became avenues and compounds. Whether this scene unfolded precisely as described is hard to prove, but it captures the imaginative leap required. When the capital of japan moved to Heian‑kyō, it was not merely following practical logic; it was enacting a vision in which the emperor’s authority radiated out from a carefully choreographed center, in harmony with mountains, rivers, and stars.

The name chosen for the new city encapsulated that aspiration. “Heian‑kyō” can be translated as “Capital of Peace and Tranquility.” In a time of factional intrigue, restless provinces, and spiritual unease, the very act of naming was a wish, almost a prayer. Like all capitals, Heian‑kyō was born of fear as much as hope: fear of Nara’s entanglements, fear of religious overreach, fear of invisible pollution. But on imperial edicts, only the hope was inscribed in black ink.

Designing a New Imperial City

Once the site was chosen, abstraction had to become geometry. Surveyors paced out the basin, planting wooden posts to mark future avenues. The new capital would echo the rectilinear perfection of Chinese models: a great north‑south axis, secondary streets at regular intervals, and a walled palace compound anchoring the northern end. From there, looking south, the emperor would gaze down the length of Suzaku Avenue, the central boulevard, upon which processions of officials, envoys, and religious dignitaries would appear like actors on a stage.

The grid was more than an urban convenience. It was a statement about order. Plotting neighborhoods in neat rectangles, assigning specific districts to ministries, artisans, and foreign traders, the planners inscribed hierarchy into the very soil. At the top, in the palace precinct, stood the Great Hall of State (Daigokuden), where court ceremonies unfolded; nearby, the inner palace housed the emperor and his consorts. To the east and west of the central axis lay the left and right capitals—administrative mirror images that helped balance power and streamline governance.

Yet, even as officials drew straight lines on maps, they had to reckon with the irregularities of lived reality. Existing shrines and sacred groves could not simply be erased. Some were carefully incorporated into the plan; others were moved or ritually pacified. The Kamo shrines, sacred to deities associated with clan ancestors and the fertility of the land, held a special place. Their presence to the northeast—considered a vulnerable, “demon gate” direction in geomantic thought—was interpreted as a form of protection, a spiritual bulwark. The alignment of Heian‑kyō with these powerful shrines would prove crucial to its identity.

As the grid took shape, lists were drawn up to assign plots to aristocratic families. The privileged were granted locations closer to the palace, along important avenues, where a steady flow of information and favor would pass their gates. Lesser officials and artisans were pushed outward, near the city’s edges. In this way, the plan of the capital, even before a single roof tile was laid, encoded the society’s stratification.

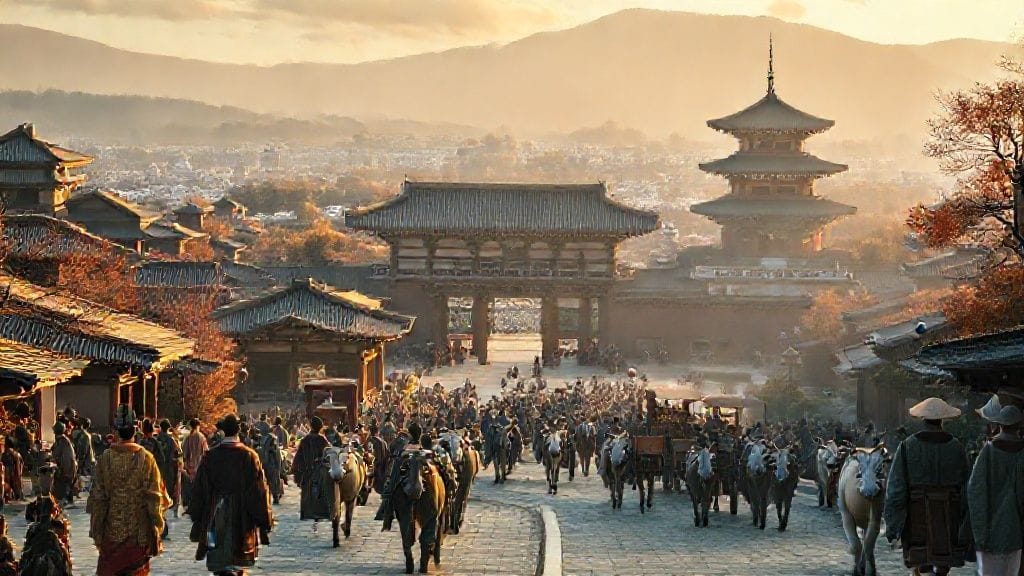

794: The Procession into Heian‑kyō

In the autumn of 794, the plan met its destiny in the form of movement. When the capital of japan moved on that particular day, it did so as a river of bodies and objects, an entire world on the march. The sun rose over Nara, glinting off pagoda tiles and the bronze curve of the Great Buddha’s shoulder, as ox‑drawn carts began to roll out of palace gates. Imperial banners fluttered—vivid reds and purples against the crisp blue sky—announcing the presence of Kammu’s entourage. Behind them came the scrolls and seals of the bureaucracy, carefully packed to ensure that government could resume in the new city without delay.

The road between Nara and the Heian basin threaded through villages that had supplied both capitals with food and labor. Ordinary people stood at the roadside, shading their eyes to watch the procession. They saw not only the emperor’s guards and ministers, but also the paraphernalia of an entire culture: lacquered chests containing ceremonial robes, musical instruments for court ensembles, brushes and inkstones belonging to poets and calligraphers, portable household shrines that linked aristocratic lineages to their ancestral kami. Some saw the moving column with awe; others with quiet resentment, knowing the taxes and corvée labor that had funded the new city would fall on their shoulders.

At the center of the procession, Kammu rode surrounded by guards, perhaps in a carriage, perhaps on horseback—sources differ on the exact detail, but they concur on the symbolism. His very movement was a public performance of authority. As the capital of japan moved, the emperor’s body was the axis around which the rest of the world rotated. Behind him, courtiers murmured speculative conversations: Would the new palace be complete in time? Which aristocratic families had secured the best plots? How far would the influence of Nara’s monks extend into the new order?

On arrival, the city was far from finished. Many streets were still rutted tracks, many plots bare save for boundary markers. Yet a skeleton existed: the palace precinct, basic administrative buildings, and some residences had been hastily raised. Temporary structures of wooden planks and thatch served where tiled halls were planned. The procession wound through this half‑formed landscape to the imperial compound, where rituals awaited to secure the move in both the earthly and heavenly realms.

Rituals, Omens, and the Spiritual Foundations of the New Capital

No capital could be inaugurated without appropriately binding it to the invisible. On arriving in Heian‑kyō, Kammu presided over a lattice of rituals designed to purify the land, appease resentful spirits, and announce to the cosmos that a new center of rule had been set on the earth. Priests recited sutras and Shinto officiants offered sake, rice, and salt to the kami at key shrines. Fires were kindled, and their smoke rose into the crisp air like questions addressed to heaven: Was this move pleasing? Would peace truly dwell in the “Capital of Peace and Tranquility”?

Omens were watched with a careful, anxious attention. A sudden storm, an earthquake tremor, or an ill‑timed eclipse could be read as a sign of displeasure, requiring further ritual. Conversely, the timely appearance of a rare bird, an unseasonably mild breeze, or the smooth course of a ritual boat on the Kamo River might be hailed as confirmation of cosmic favor. Court astrologers and calendrical experts poured over sky charts, aligning coronation and dedication ceremonies with propitious days.

One of the most important spiritual relationships cemented in these early years was with the Kamo deities. Processions to the shrines that guarded the city’s northeast became recurring events in the court’s calendar. Over time, the Aoi Matsuri (Hollyhock Festival) emerged as one of Heian‑kyō’s signature rituals, involving lavish parades from the imperial palace to the Kamo Shrines, with courtiers dressed in archaic costume. Such performances were not merely picturesque; they constantly reaffirmed the pact between city, sovereign, and the land’s ancient powers.

At the same time, Kammu carefully limited the footprint of major Buddhist institutions within the city proper. He encouraged the growth of new schools of Buddhism—such as the Tendai school on Mount Hiei, founded by Saichō—that would be physically and institutionally distinct from the Nara establishments. By fostering powerful but more distant monasteries, the emperor tried to balance his need for religious support with his desire to escape Nara’s suffocating embrace. When the capital of japan moved, the struggle to define its spiritual ecology moved with it.

Life in Early Heian‑kyō: Streets, Markets, and Mansions

For all its cosmic pretensions, Heian‑kyō was also a place where people simply lived. In the first decades, the city smelled of fresh‑cut wood, damp earth, and smoke from hearth fires curling into the morning mist. Workers trudged through muddy streets carrying timbers, tiles, and stones. Children of laborers and lower officials played in the vacant lots between building sites, weaving their games through the skeleton of the new urban grid.

Two markets—the Eastern and Western Markets—were laid out near the center of the city, each a bustling rectangle of stalls and storehouses. Here, provincial goods poured in: rice, salt, dried fish, silk, lacquerware, and exotic wares brought by intermediaries who had dealt with Yuan or Tang merchants across the sea. Government officials monitored weights and measures, collected taxes, and ensured that the city’s appetites were fed. For humble vendors, Heian‑kyō offered opportunities that had not existed in scattered rural settlements: a dense concentration of customers, including aristocrats with a taste for rare objects.

Closer to the palace, the aristocratic mansions rose, enclosed by walls of earth and wood. Within them, gardens were sculpted with ponds and miniature hills meant to echo famous landscapes. Bamboo groves whispered in the wind; plum and cherry trees marked the seasons with their blossoms. Interiors were defined by screens and sliding doors rather than permanent walls, their configurations shifting with the needs of ceremonies, visits, and private moments. Light filtered through wooden lattices, playing on lacquered floors and silk curtains.

Life followed the rhythms of the court calendar. Officials rose before dawn to report for duty, their ranks and offices visible in the colors and patterns of their robes. Messengers darted through streets bearing written orders, while scribes hunched over low tables, copying documents with meticulous strokes. At night, torchlight and lamplight flickered in the palace, while in poorer quarters, households huddled around single hearths. The capital of japan moved in 794, but in the years that followed, it settled into a set of daily practices and routines that slowly turned a construction site into a living organism.

Reordering Power: Aristocrats, Monks, and the Emperor

Politically, the move to Heian‑kyō rebalanced an unstable triangle: emperor, aristocracy, and religious institutions. Kammu’s initial goal had been to free the throne from the spatial proximity and entrenched influence of Nara’s monasteries. By physically distancing the court, he hoped to reassert imperial initiative. For a time, this seemed to work. Monks from Nara could still petition the throne, but they did so from a remove; their temples no longer loomed within walking distance of the palace.

However, the void near the throne did not remain empty. Aristocratic families, especially the Fujiwara, seized the opportunity. They invested heavily in their new residences, cultivated close relationships with key officials, and continued the strategy that had served them so well in Nara: providing imperial consorts. Over the 9th and 10th centuries, Fujiwara regents would come to dominate the politics of Heian‑kyō, often ruling in the name of child emperors. As historian George Sansom observed in his survey of early Japanese history, the political center of gravity slipped from the emperor’s direct hand into the grip of these great families (see Sansom, A History of Japan to 1334).

Meanwhile, new Buddhist institutions arose in the hinterland of the capital. Saichō’s Tendai center on Mount Hiei and Kūkai’s Shingon base at Mount Kōya were physically removed from the city yet spiritually influential. Over time, they too accumulated land and followers, and their abbots negotiated with the court for privileges. The tension Kammu had tried to resolve did not vanish; it migrated and evolved. The capital of japan moved, but the dance between throne and temple only adopted new steps.

This reordering of power had human consequences within the city. Patronage networks determined appointments, marriages, and even who might be allowed to retire into religious life with comfort and prestige. For an ambitious young noble in Heian‑kyō, success meant navigating these currents skillfully: studying Chinese classics to pass examinations, cultivating poetic and musical talents to shine in salons, aligning oneself with patrons who could open doors. For those outside the webs of influence, the capital’s brilliance merely highlighted their exclusion.

Women, Letters, and the Birth of a Courtly Culture

In the centuries after the move, Heian‑kyō gave birth to a remarkable flowering of literature and aesthetics, much of it crafted by women of the court. In the corridors and screened chambers of aristocratic mansions, ladies‑in‑waiting composed poems on scented paper, traded diaries, and recorded the subtleties of romance, rivalry, and spiritual yearning. Their words would come to define how later generations imagined the Heian age.

The capital of japan moved not only in physical space but linguistically and culturally. At first, Chinese remained the prestige written language for official documents and learned treatises. Over time, however, a phonetic script derived from simplified Chinese characters—kana—gave Japanese a new written form. Women, often excluded from the most formal classical Chinese education, embraced kana for personal writing. Its curves and flows lent themselves to rapid, intimate expression: the flicker of an emotion during a moon‑viewing party, the ache of a lover’s absence, the melancholy of autumn rain on a palace roof.

Works like Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji and Sei Shōnagon’s The Pillow Book, written in the early 11th century, are products of this environment. They describe an already somewhat nostalgic Heian‑kyō, one in which the rituals established in Kammu’s time had become the unquestioned stage of life. Through their eyes, the city appears as a network of mansions, gardens, and ceremonial spaces, more than as a fortress or marketplace. Their concern is with the delicate calibrations of status, emotion, and beauty that defined the aristocratic world.

Yet behind the refined brushwork lay vulnerability. A woman’s security depended heavily on the fortunes of her natal and marital families. A change in political favor could see her moved from a lavish mansion to a modest dwelling on the city’s outskirts. Illness could sweep through the capital, turning elegant gatherings into sites of whispered fear. In this sense, the literature of Heian‑kyō is haunted by impermanence. The city that seemed eternal when the capital of japan moved to it in 794 was, in lived experience, always fragile—susceptible to fire, flood, and the fickleness of human hearts.

From Political Center to Cultural Icon: The Making of Heian Japan

By the 10th century, Heian‑kyō had acquired a dual identity. It was, of course, the administrative and ceremonial heart of the realm. Edicts issued from its palace still carried the force of law in distant provinces, and embassies, when they came, were received according to strict protocol. But increasingly, the city also became a symbol—a distilled image of what it meant to be “Japanese” in a new, more self‑conscious sense.

Part of this shift came from changing relations with the continent. Official embassies to Tang China ceased after the late 9th century, partly due to political upheavals in China and partly due to court debates about the costs and benefits of such missions. Freed from the constant pressure to adapt to the latest Chinese norms, Heian‑kyō’s elites turned inward, elaborating a distinctive court culture. They still revered Chinese classics and models, but they also cultivated uniquely local tastes in poetry, clothing, and ceremony.

In this process, the memory of the capital’s movement itself became part of a founding myth. The story that “the capital of japan moved” to a place of peace and refined civilization helped legitimize the city’s symbolic authority. To live in Heian‑kyō was to inhabit the center not only of political power but of an entire world of meaning. Provincial officials, summoned to serve at court, learned its codes eagerly, then carried their impressions back to their home districts. Some tried to recreate miniature Heian worlds in provincial capitals, with small gardens and literary gatherings that echoed the great city. Others simply revered it from afar, offering local products and taxes in the hope of a favorable nod from its distant rulers.

Over time, the term “Heian period” came to encompass the centuries during which the capital remained at Heian‑kyō, from 794 until the late 12th century. Historians debate the exact character of the age, but most agree that the cultural achievements of this era—poetry anthologies like the Kokinshū, prose masterpieces like Genji, delicate painting styles on folding screens—are inseparable from the physical and social environment of the capital. As Andrew Goble and other modern scholars of Heian society have noted (see Goble, Kenmu, for contextual analysis), the city’s grid, its rituals, and its concentration of elites shaped not only politics but sensibility itself.

The Hidden Costs: Peasants, Soldiers, and Peripheral Provinces

While Heian‑kyō glittered, the countryside bore its weight. The capital of japan moved to a new location, but it did not move alone; it dragged with it an expanded appetite for resources. Building and maintaining the city required timber, stone, metals, and above all rice—rice to pay officials, to feed workers, to fill the storehouses that secured the regime against famine. Tax registers swelled with demands on villages hundreds of kilometers away, where farmers lived in houses of packed earth and thatch, far removed from the polished floors of the palace.

The ritsuryō system of codes and land distribution, modeled initially on Chinese precedent, had aimed to bind the empire together through a network of state‑directed fields and tax obligations. By the time Heian‑kyō was several generations old, however, this system was fraying. Powerful local families, some with ties to the court, carved out semi‑autonomous estates (shōen), obtaining tax exemptions and protective charters. Ironically, the need to reward loyal aristocrats and religious institutions with land undermined the very fiscal base that supported the capital.

For peasants absorbed into these estates, the change could be double‑edged. On one hand, they sometimes gained more predictable obligations to a local landlord rather than to distant bureaucrats. On the other, they lost direct recourse to the central government and could be squeezed by local power‑holders. When drought or war struck, the glittering rituals of Heian‑kyō offered little comfort to those watching their fields crack under the sun or their storehouses emptied by raiders.

To defend distant frontiers and suppress rebellions—especially in the northeast, where the court labeled local groups “Emishi”—the government relied increasingly on provincial warriors. These men, adept at mounted archery and rugged campaigning, formed a very different social world from the perfumed courtiers of Heian‑kyō. Yet their successes and failures were tightly bound to the capital’s fate. Victorious warriors sought titles and recognition from the court; their clans eventually realized that their military power could be turned inward, against rival court factions. In this sense, the day the capital of japan moved to Heian‑kyō also set in motion long‑term dynamics that would, centuries later, culminate in the rise of the samurai and the eclipse of the court.

Heian‑kyō Under Threat: Rebellions, Disease, and Fire

No city remains untroubled for four centuries. Heian‑kyō, for all its rituals of protection, was repeatedly tested. Epidemics swept through its dense neighborhoods, carrying off children and venerable ministers alike. In an age before germ theory, these outbreaks were interpreted as signs of cosmic imbalance: perhaps an angry spirit had not been properly placated, perhaps a calendar error had offended the heavens. Exorcists and monks found their services in high demand, staging elaborate rites to drive away unseen demons.

Fire was an even more constant threat. Built largely of wood and paper, the city could go up in flames with terrifying speed. Chronicles record nights when an orange glow turned the sky above the palace into a false dawn, when entire rows of mansions burned, their treasures consumed in hours. Each time, rebuilding had to occur, taxing already strained resources. These disasters stripped away the illusion of permanence that the city’s geometric layout tried to project. Behind every smooth avenue lay the memory of earlier versions of the same district, lost to conflagration.

At the political level, major rebellions shook the capital’s sense of security. The uprisings of Taira no Masakado in the east and Fujiwara no Sumitomo in the west during the 10th century, and later the catastrophic Hōgen and Heiji disturbances in the 12th, revealed that provincial warriors and discontented aristocrats could challenge the court’s authority. Bands of armed men occasionally appeared in Heian‑kyō itself, clashing in streets that had been designed for orderly processions, not for warfare.

By the late Heian period, the Taira and Minamoto warrior clans, originally provincial protectors, were battling for control of the capital. When Minamoto no Yoritomo ultimately prevailed and established a new military government in Kamakura toward the end of the 12th century, the political centrality of Heian‑kyō was fatally wounded. Yet, significantly, even as effective power moved east, the city—now more commonly called Kyoto—retained its imperial and cultural prestige. The capital of japan moved again in a political sense, but not with the same ceremonious finality as in 794; instead, power simply drained away, leaving the city’s palaces as luminous shells of an older order.

The Long Echo: From Heian‑kyō to Kyoto and Modern Memory

Over the centuries, Heian‑kyō shed its original name in daily speech and became Kyoto, simply “the Capital.” Fires, wars, and urban growth altered its layout, and many of Kammu’s original buildings disappeared, but the basic orientation remained. The imperial palace, though rebuilt and relocated slightly within the city, continued to mark a northern anchor. The Kamo Shrines kept watch at the city’s edge. Markets, temples, and later merchant districts filled in the grid’s empty spaces.

Even after the Tokugawa shogunate fixed its military headquarters in Edo (modern Tokyo) in the 17th century, Kyoto remained the seat of the emperor. Poets and pilgrims still treated it as the heart of tradition. When the Meiji Restoration of 1868 formally transferred the capital functions to Tokyo, the move was laden with symbolism: a modernization project that looked eastward, toward the Pacific and beyond, rather than inward to the classical court. Yet Kyoto’s status as a cultural capital only deepened. Its temples and shrines, many of them heirs to Heian‑period foundations, became guardians of “old Japan” in the modern imagination.

In this long perspective, the day the capital of japan moved to Heian‑kyō in 794 stands not just as a discrete event but as the inception of a pattern. Japanese political centers have shifted—Nara to Heian‑kyō, Heian‑kyō to Kamakura, later to Edo/Tokyo—yet each move has had to reckon with the spiritual and cultural weight of its predecessors. Kyoto today, with its festivals, its old streets, and its role as a historical touchstone, still lives in the shadow of Kammu’s decision. Tourists walking down modern avenues may not realize that their steps follow lines first inscribed by 8th‑century surveyors, but the city’s bones remember.

Modern historians, drawing on archeological surveys, court chronicles like the Shoku Nihongi, and comparative urban studies, continue to piece together what Heian‑kyō looked and felt like in various centuries. The city is both a physical artifact and a palimpsest of stories—a place where the abstraction “capital” took corporeal form, then gradually ceded it, leaving behind a unique blend of monument and memory.

Historians’ Debates: Why the Capital Move Mattered

Scholars have long debated how to interpret the significance of the 794 move. Was it primarily a spiritual maneuver, a flight from the perceived pollution and over‑mighty temples of Nara? Was it a calculated political strategy by Kammu to consolidate imperial authority and sidestep entrenched interests? Or was it, more prosaically, a response to practical concerns about geography, resources, and Nara’s limited capacity for further growth?

Most contemporary research suggests a convergence of factors. Archeological evidence indicates that the Yamashiro basin offered better access to river transport and a more flexible urban space than constrained Nara. Textual sources, meanwhile, emphasize both the dangers of Nagaoka’s unlucky omens and Kammu’s unease with Nara’s monasteries. As Conrad Totman and other environmental historians have noted, the choice of capital sites in premodern Japan often reflected subtle calculations about resource flows, not merely court intrigue.

Debate also centers on the long‑term effects. Some historians argue that the move entrenched the ritsuryō system for another century, allowing the court to refine and domesticate imported Chinese models into a distinctively Japanese political culture. Others counter that the same move accelerated the concentration of power in aristocratic hands, laying the groundwork for imperial marginalization and the rise of warrior rule. In either view, the fact that the capital of japan moved to Heian‑kyō is treated as a pivot point—one of those rare dates that resonate far beyond their single year.

Finally, cultural historians highlight how the new capital’s spatial and social arrangements shaped aesthetic ideals. The long, straight avenues offered vistas for processions; the enclosed gardens inspired new metaphors in poetry and painting. A city designed, in part, to escape the crushing presence of religious institutions ended up fostering a softer but no less powerful sacrality of beauty and refinement. In this reading, the true legacy of 794 lies less in politics than in sensibility—the way Japanese writers, artists, and even modern filmmakers imagine courtly grace and tragic impermanence, evoking Heian‑kyō as a dream of what a capital could be.

For further academic perspectives on these debates, readers may consult works such as John Whitney Hall’s chapters in The Cambridge History of Japan, which synthesize political, economic, and cultural analyses of the Nara‑Heian transition, or Karl Friday’s studies of early samurai, which trace how distant military developments were nonetheless entangled with the city born when the capital of japan moved in 794.

Conclusion

When the capital of Japan moved to Heian‑kyō in 794, a wooden stake driven into damp earth became the axis of a new world. From that decision flowed a reconfiguration of power away from Nara’s temples, the construction of a carefully planned city, and the slow evolution of a court culture whose echoes still shape how Japan imagines its classical past. The move was at once highly practical—to a basin with better geography and room to grow—and intensely symbolic, framed as a quest for peace, purity, and righteous rule. Over the centuries, Heian‑kyō would witness splendor and catastrophe, from the composition of The Tale of Genji to the fires and rebellions that heralded the rise of the samurai.

The city’s story reminds us that capitals are never merely coordinates on a map. They are living compromises between terrain, belief, ambition, and fear. Kammu sought to escape spiritual pollution and political stalemate; in doing so, he created a stage on which new tensions—between emperor and aristocrats, between court and provinces—would play out. The move did not solve the fundamental challenges of ruling a diverse archipelago, but it transformed the terms on which those challenges were addressed. Today, Kyoto’s temples, shrines, and street grid still bear silent witness to that transformation.

To say that “the capital of japan moved” in 794 is therefore to compress a vast human drama into a flat phrase. Unfolded, it is a story of processions under autumn skies, of surveyors in misty fields, of peasants filling tax carts, of women at low tables composing lines that would outlive dynasties. It is a reminder that when power decides to relocate itself, it must persuade not only ministers and generals but also the land, the gods, and the imagination of future generations. In that sense, the journey from Nara to Heian‑kyō has never entirely ended; it continues in every attempt to make sense of where Japan’s true “center” lies.

FAQs

- Why did Emperor Kammu move the capital from Nara to Heian‑kyō?

Most historians agree that Kammu moved the capital to escape the growing political influence of Nara’s Buddhist monasteries, to avoid places considered spiritually polluted by past crises, and to take advantage of the more favorable geography and resources of the Yamashiro basin. The move also allowed him to signal a fresh start and reassert imperial authority in a new setting. - Was Heian‑kyō completely new, or did people already live there?

The site of Heian‑kyō was not empty wilderness; it contained small settlements and important shrines, especially the Kamo Shrines. However, the planned grid city, with its palace complex, wide avenues, and administrative districts, was a new construction imposed over this older sacred landscape. - How closely was Heian‑kyō modeled on Chinese capitals?

Heian‑kyō’s basic plan—with a north‑south central avenue, a northern palace compound, and a rectangular grid of streets—was clearly inspired by Tang dynasty capitals like Chang’an and Luoyang. Yet it adapted these models to local topography and spiritual concerns, incorporating existing shrines and paying close attention to geomantic orientations. - Did the move to Heian‑kyō immediately weaken Nara’s temples?

The move reduced the direct spatial influence of Nara’s temples over the court, but it did not instantly strip them of power or wealth. They remained important religious and economic centers, even as Kammu and his successors promoted new Buddhist institutions, such as Tendai on Mount Hiei, to counterbalance them. - How long did Heian‑kyō remain Japan’s capital?

Heian‑kyō, later known as Kyoto, served as the formal imperial capital from 794 until the late 19th century, although real political power shifted to other cities, such as Kamakura and Edo, at various points. The Meiji government’s decision in 1868 to move the emperor and central government to Tokyo marked the end of Kyoto’s role as the active political capital. - What are some good academic sources on the move to Heian‑kyō?

Useful starting points include George Sansom’s A History of Japan to 1334, John Whitney Hall’s contributions to The Cambridge History of Japan, and studies of Nara‑Heian religious politics such as Mikael Adolphson’s The Teeth and Claws of the Buddha. These works draw on court chronicles, archeology, and comparative urban history to analyze why the capital of japan moved and what the change meant.