Table of Contents

- A Young Emperor in a Waning Dynasty

- The Eastern Han After the Firestorm: A Fragile Restoration

- Birth of a Prince: Liu Bao’s Early Years in the Shadow of Power

- Court of Masks: Empress Dowager Deng and the Web of Regents

- Testing the Heir: Education, Ritual, and the Making of an Emperor

- The Death of an Emperor and the Quiet Struggle for Succession

- Year 125: The Day Emperor Shun of Han Took the Dragon Throne

- Rituals, Omens, and the Mandate of Heaven

- Behind the Curtain: Factional Politics in the Early Shun Reign

- Life in the Capital: Luoyang Under a New Son of Heaven

- Frontiers on Fire: Qiang Uprisings and the Western Crisis

- Scholars, Memorials, and the Moral Burden of Rule

- Inside the Palace Walls: Family, Consorts, and Silent Tragedies

- The People’s Dynasty? Taxation, Famine, and Everyday Survival

- Portents of Decline: Corruption, Eunuchs, and the Fracturing Court

- The Final Years of Emperor Shun of Han

- Legacy of a Gentle Ruler in an Age of Gathering Storms

- Echoes Through Time: How Later Generations Remembered Emperor Shun

- Conclusion

- FAQs

- External Resource

- Internal Link

Article Summary: In the year 125 CE, as the Eastern Han dynasty stood at a fragile midpoint between past glory and future collapse, a young prince named Liu Bao ascended the throne as emperor shun of han. His rise was not a thunderclap of conquest but a quiet, carefully managed transition orchestrated by powerful regents and an aging empress dowager determined to preserve stability. This article follows his journey from vulnerable child in the palace to a monarch struggling to uphold the Mandate of Heaven while the frontiers burned and the bureaucracy decayed. Through narrative scenes, political analysis, and human portraits, it explores how his reign captured both the earnest hopes and the buried fears of a dynasty already in decline. We trace the social impact of war, famine, and court intrigue on peasants, scholars, soldiers, and palace women whose lives intersected with his. The story shows how emperor shun of han, often labeled a mild and overshadowed ruler, nonetheless left a distinctive imprint on the era’s institutions and memory. It also asks what it means to be a good emperor in a bad time, and how posterity judges such a figure. In doing so, it places his brief, troubled reign within the long arc of Chinese imperial history, where omens in the sky and whispers in the corridors alike could decide the fate of millions.

A Young Emperor in a Waning Dynasty

The story of Emperor Shun of Han begins at dusk, not at dawn. When the twelve-year-old boy ascended the dragon throne in 125 CE, the Eastern Han dynasty had already lived through a century of triumph and trauma. The gleaming façade of imperial power still impressed visitors to Luoyang—the wide avenues, the palaces dripping with vermilion and gold, the solemn drums that marked the hours. Yet beneath the ritual order, nerves were frayed, and confidence in the future was ebbing away.

The dynasty had been restored in 25 CE by Liu Xiu, Emperor Guangwu, after the collapse of the Western Han. His descendants had tried to blend stern legal administration with the ethical ideals of the Confucian classics. But each generation paid a price in blood and legitimacy to hold the empire together. By the time emperor shun of han entered the world, the dynasty was dealing with a tangled web of problems: powerful landlord clans squeezing the peasantry, endlessly recurring rebellions on the northwestern frontier, and a court increasingly dominated by regents, empresses dowager, and eunuchs.

The new emperor was born Liu Bao, a child of the imperial clan, raised behind carved screens and silk curtains. His step into power was not the triumph of a conquering hero, but the elevation of a boy whose name had been whispered in corridors and discussed in closed council meetings. At the moment he received the imperial seal, he inherited not just vast territories and millions of subjects, but also decades of unresolved crisis and a legacy of uneasy compromises. It is this contrast—between the innocence of youth and the heaviness of history—that gives his accession its poignant, almost cinematic tension.

But this was only the beginning. To understand why the ascent of emperor shun of han mattered, we must first walk backward through time, into the corridors of power that shaped him and the empire he came to rule.

The Eastern Han After the Firestorm: A Fragile Restoration

Half a century before Emperor Shun took the throne, the Han world had already survived a cataclysm. The usurpation of Wang Mang, the flood of the Yellow River that drowned entire districts, and the massive Red Eyebrows rebellion had ripped apart the old Western Han order. When Liu Xiu reestablished imperial control and founded the Eastern Han in Luoyang, he inherited a land studded with ruined towns, orphaned children, and abandoned fields. His task was to convince a traumatized populace that Heaven still favored the Liu clan and that the Mandate of Heaven had not evaporated into chaos.

Under Guangwu and his immediate successors, the Eastern Han launched a careful project of reconstruction. Taxes were reduced, corvée labor obligations eased, and amnesties announced to win back hearts. Scholars were once more invited to the capital to edit the Confucian classics and to advise on ritual policy. Over time, granaries filled, trade routes reopened, and local garrisons pushed back nomadic raiders. The official histories would later praise this period as a measured restoration of order, a kind of second founding of the dynasty.

Yet behind the celebrations, cracks widened. As central authority worked to recover, regional elites accumulated vast tracts of land and consolidated private militias. The legal distinction between commoners and great clans sharpened. Household registers, in theory used for fair taxation, increasingly reflected the interests of those who could bribe local officials. For every granary built, there was a village quietly slipping out of effective state control.

This was the institutional world into which emperor shun of han was born—a recovered yet precarious empire. The palaces of Luoyang gleamed brighter than ever, but the connection between throne and countryside was thinning. The child who would one day rule was destined to sit atop a pyramid whose base was already, invisibly, beginning to crumble.

Birth of a Prince: Liu Bao’s Early Years in the Shadow of Power

Liu Bao entered the world in 115 CE, a time still officially classified by court astrologers as one of Heavenly favor, but already full of anxious omens. Born into the imperial Liu clan, he spent his infancy encircled by women: nurses, attendants, and the formidable figures of the inner court. While the details of his earliest days have been softened by time, the outline is clear. From the moment he could grasp a jade rattle, he was watched—not just with maternal affection, but with political calculation.

In the Eastern Han palace, even toys had meaning. Miniature chariots, ritual vessels, and bamboo slips with simple characters were presented not only as playthings, but as the first steps in an education toward rulership. A boy of the blood was never simply a child. He was a potential pivot of power, a future bargaining chip in the rivalries that raged behind painted screens.

The sources suggest that Liu Bao’s temperament was gentle, reserved, inclined toward reflection rather than command. Later historians would describe Emperor Shun of Han as benevolent but indecisive, a man of good intentions often overwhelmed by events. One can imagine, in those early years, a watchful boy standing by a latticed window, listening silently as distant drums announced changing watches, while conversations among elders fell abruptly quiet whenever he stepped too close.

His birth brought both hope and risk. A prince strengthened the line, but also multiplied possibilities for conflict. Other branches of the clan watched his growth with interest that might, in an instant, turn into fear. Empresses and consorts measured their children against him, calculating who might one day be named heir. The inner palace, outwardly serene, was a landscape of hidden rivalry; every cradle was also a potential fulcrum of political catastrophe.

As Liu Bao learned his first characters, he was also, without yet knowing it, learning to inhabit a role that demanded he be more symbol than person. That tension—between the human child and the imperial sign—would define his entire life.

Court of Masks: Empress Dowager Deng and the Web of Regents

No story of emperor shun of han can be told without Empress Dowager Deng Sui. Widowed consort of Emperor He and then regent to his successor Emperor An, she was the central axis of power during the years when Liu Bao grew from child to adolescent. Intelligent, politically shrewd, and deeply familiar with the rituals of imperial authority, she ruled from behind the curtain, issuing edicts in the name of boy emperors and managing a court seething with ambition.

Deng Sui understood better than most that the Eastern Han throne was no longer an unassailable peak, but a contested seat. Her strategy was both conservative and pragmatic: preserve the authority of the dynasty, curb obvious abuses, and keep the most dangerous factions—whether military commanders, prominent clans, or blocks of eunuchs—from dominating the palace. To do this, she needed pliable emperors, boys who would obey her guidance until they came of age, and ideally beyond.

Within this system, royal princes like Liu Bao occupied an ambiguous position. They were essential to ensure the continuity of the line, but dangerous if their personal networks grew too strong. Under Deng’s watch, the education and placement of such princes were carefully managed. Their visits to the capital were monitored; their tutors were chosen with an eye to loyalty as much as learning.

At court, masks were everything. Deference might hide contempt, and flowery memorials might conceal veiled criticisms. The regent-empress played a delicate game, rewarding some officials to balance others, allowing certain debates to proceed while silencing more radical voices. In this highly orchestrated environment, young Liu Bao learned an early lesson: that the empire was run less by the thunder of imperial decrees than by the quiet choreography of a handful of people around the throne.

It is astonishing, isn’t it, how the fate of millions of peasants plowing their fields depended on the conversations of a few dozen individuals in lacquered halls? Yet this was the reality of Eastern Han governance. And as years passed and emperors sickened and died, it became clear that one day, perhaps sooner than expected, Liu Bao himself might be summoned to sit where they had sat, under the same watchful eyes.

Testing the Heir: Education, Ritual, and the Making of an Emperor

To be groomed as a possible heir in the Eastern Han was to be enrolled in a vast, demanding theater of learning. As Liu Bao grew older, his days followed the rhythm of a Confucian script refined over generations. At dawn, he rose to perform ritual ablutions, dressing in carefully chosen robes that signaled his rank and responsibilities. Before breakfast, there might be recitation: lines from the Classic of Filial Piety, passages of the Analects or the Book of Documents, each line not only a linguistic challenge but a moral imperative.

His tutors drilled him in history, using the stories of sage-kings and failed rulers as stark warnings. The tyrant Zhou of Shang and the decadent rulers of later dynasties were held up as cautionary tales—men whose cruelty or indulgence lost them the Mandate of Heaven. By contrast, ideal monarchs like Yao and Shun were praised for humility and attention to the people’s needs. Later scholars would note the irony that “Shun” would become the reign title of this very prince, framing him, intentionally or not, in the lineage of those mythical paragons.

Beyond text, his education was tactile and performative. He practiced archery, not only as a martial skill, but as a ritual exercise meant to align the body with order and precision. He studied music, understanding that certain harmonies were believed to reflect cosmic balance. He was instructed in sacrifice: how to bow at the altars of Heaven and Earth, how to handle jade tablets and bronze vessels, how to speak the formulaic phrases that acknowledged the ancestors and the spirits of the land.

In quieter hours, he learned the geography of the empire: the fertile plains of the Central Region, the troubled commanderies of the northwest, the humid rice fields of the south. Maps unfurled before him like silent admonitions. Each river and mountain pass represented both a responsibility and a vulnerability. As one later historian wrote in the Hou Hanshu, “An emperor must bear the realm upon his heart as the farmer bears his plow” (a paraphrase of a sentiment common in Han political discourse).

Through this long apprenticeship, the boy Liu Bao was gradually reshaped into emperor shun of han: not yet by name, but in expectation. Those around him weighed every reaction—whether he showed mercy to a punished servant, whether his questions betrayed curiosity or indifference. These were not trivial matters. In a polity where personality and policy were intimately linked, the character of a single man could shift the lives of millions.

The Death of an Emperor and the Quiet Struggle for Succession

In 125, the axis tilted. Emperor An of Han, whose reign had already seen mounting troubles on the frontiers and in the capital, fell ill. In the palace, physicians burned herbs and prepared decoctions, but their efforts only seemed to delay the inevitable. Within the inner chambers, Empress Dowager Deng and senior eunuchs conferred in low, urgent tones. They knew as well as anyone that the death of an emperor was the most perilous moment for a dynasty short of outright rebellion.

The question that consumed them was simple and lethal: who would succeed? There was no shortage of Liu princes, each with his own supporters. Some were older and perhaps more experienced than Liu Bao, but came with the baggage of entrenched patronage networks and potential hostility from Empress Deng’s allies. Others were children, malleable but too young to command even the superficial respect of the court.

Liu Bao presented a middle path. Young enough to be guided, old enough to embody a measure of dignity, he was also politically convenient. His branch of the family did not yet possess the kind of power that might alarm Deng’s faction. In the swirl of intrigue, his very relative insignificance became his greatest asset.

Historians would later reconstruct these events through fragmentary memorials and retrospective judgments, but the atmosphere in Luoyang in those weeks must have been electric. Messengers ran between ministries. Clan leaders met privately in their mansions, calculating how to secure their fortunes under whichever prince prevailed. Soldiers at the palace gates stood a little more rigidly, aware that coups had occurred under circumstances not unlike these.

Yet the struggle, for all its intensity, never exploded into open conflict. Through a series of controlled consultations and carefully staged announcements, Empress Dowager Deng maneuvered the process. When Emperor An finally died, the decision had effectively already been made. Liu Bao would be called to ascend the throne.

For the boy himself, the summons must have landed like both an honor and a sentence. The world he knew—structured, supervised, protected—was about to be replaced by one in which every choice he made could ripple through the empire. In a single stroke, childhood was over.

Year 125: The Day Emperor Shun of Han Took the Dragon Throne

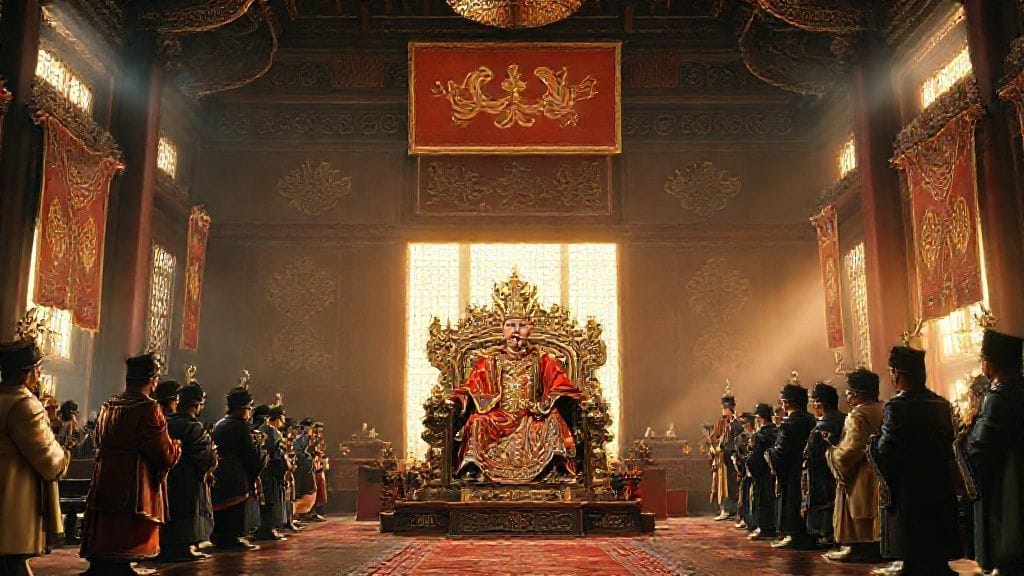

The accession of emperor shun of han unfolded as both ritual pageant and political maneuver, a carefully choreographed performance designed to reassure the cosmos and the populace that the Mandate of Heaven remained intact. In Luoyang, the capital woke before dawn. Gongs sounded from the watchtowers, summoning officials in layered robes to the palace. Dust rose from the hooves of their horses as they converged on the southern gates, where banners bearing the imperial emblem snapped in the morning wind.

Inside, attendants moved with solemn urgency. The boy who was about to become emperor was ceremonially bathed and dressed. Layers of silk—first undergarments, then outer robes embroidered with dragons and mountain motifs—were fitted and tied. Jade ornaments were hung at his waist, clinking softly as he walked. An official held the new reign title ready: “Shun”, evoking docility, smoothness, and the ancient sage-king famed for his humility and virtue.

The core of the ceremony was the transfer of symbols. Before assembled ministers, the imperial seal was presented to Liu Bao. As he extended his hands, the hall seemed to hold its breath. Accepting the seal, he accepted also the crushing abstractions it represented: authority over life and death, the duty to sacrifice for the people, the claim to stand between Heaven and Earth as mediator and guarantor of order. He was barely twelve.

Outside the palace, the accession spread through whispers and proclamations. Town criers read out the formal edicts: the mourning for the deceased emperor, the enthronement of the new one, the expected acts of grace that usually accompanied such a transition—reductions in penalties, remissions of certain taxes, the release of some prisoners. In distant villages, peasants heard the news days or weeks later, when local magistrates posted notices on wooden boards and announced that a new “Son of Heaven” now ruled in Luoyang.

For most of them, daily life did not suddenly transform. They still had fields to till, debts to pay, obligations to fulfill. But in the mental universe of Han China, the enthronement of a new emperor was momentous. It meant that the dynastic cycle continued for at least another turn. Whether this turn would be upward, toward renewed prosperity, or downward, toward the chaos that so many remembered from stories of the earlier civil wars, remained to be seen.

Within the palace, as the ceremonies concluded and the last ritual bows were made, emperor shun of han sat, perhaps uncomfortably, on the dragon throne. Below, ministers recited formulaic phrases pledging loyalty. Behind him, unseen by most, stood the shadows of regents and advisors who had made this moment possible and who intended to guide what followed. The boy’s face, recorded only in the vaguest terms by later chroniclers, is left to our imagination: perhaps a mix of fear, determination, and the barely suppressed thrill of someone suddenly elevated above all others.

Rituals, Omens, and the Mandate of Heaven

No accession in Han China was complete without reading the skies. As the new era title was proclaimed and bronze bells rang through the capital, court astrologers turned their eyes toward the heavens, searching for confirmation—or warning—of Heaven’s will. The ideology that underpinned imperial power insisted that cosmic order and human governance were linked. Eclipses, comets, strange halos around the sun: all could be interpreted as commentary on an emperor’s virtue or failings.

In the months surrounding Emperor Shun’s rise, records hint at unusual phenomena: earthquakes in distant commanderies, heavy rains where there should have been light drizzle, perhaps the dim crossing of a comet. Each event prompted memorials from scholar-officials, who used them as platforms to press for moral and administrative reforms. “When Heaven shows its displeasure,” one such writer argued in a memorial preserved in later texts, “it is not the stars themselves that accuse us, but the tears of the people, reflected in the sky.”

As emperor shun of han began his reign, these voices urged him to reduce harsh punishments, to curb the influence of corrupt officials, and to attend more directly to the welfare of the people. Whether the young emperor fully grasped the philosophical weight of these arguments is unknowable, but the institutional machinery ensured that such memorials reached the throne and were read, if not always acted upon.

Meanwhile, rituals multiplied. The new emperor presided over sacrifices to Heaven at the southern suburbs of the capital, to Earth at the northern altar, to his ancestors in the ancestral temple. In each ceremony, he performed precise gestures, recited ancient invocations, and participated in processions meant to manifest harmony between the ruler, the natural world, and the moral order.

These rituals were not mere theater. They were how the Han state imagined itself: as an organism whose center—embodied in the emperor—had to be correctly aligned for the entire body to function. When emperor shun of han stood on the raised altar, incense swirling around him, he was less an individual and more a human node in a cosmic network. If he faltered, or if his government strayed from virtue, the network, it was feared, would twist, and chaos would follow.

Behind the Curtain: Factional Politics in the Early Shun Reign

Although the edicts now went out in Emperor Shun’s name, power remained, for a time, where it had long resided: behind curtains and in side chambers. Empress Dowager Deng continued as regent, exercising effective control over major appointments and policy. Her network of relatives and trusted officials occupied key positions in the Secretariat and the Palace Administration. Eunuchs, increasingly influential as intermediaries between the inner palace and the outer bureaucratic world, also began to assert themselves more forcefully.

In this environment, the young emperor’s wishes could easily be filtered, reshaped, or simply ignored. But he was not entirely without agency. Anecdotes preserved in later histories suggest that even as a teenager, emperor shun of han showed a personal inclination toward clemency and attention to petitions from the wronged. In one case, he reportedly intervened to spare a low-ranking official from execution after being convinced that the man had been unjustly accused—an early sign of the benevolence that would later define his reputation.

Still, factional tensions simmered. Some officials chafed under the dominance of the Deng clan and awaited the day when the emperor could rule in his own right. Others hitched their fortunes to the empress dowager’s chariot, seeing in her regency a guarantee of stability and personal promotion. Eunuchs, whose proximity to the emperor gave them unique opportunities, navigated between these groups, sometimes serving as neutral channels, sometimes as power brokers in their own right.

The court became a kind of pressure cooker. Every death—of a key minister, a princely rival, or an aging dowager—threatened to rearrange the entire political constellation. The accession of emperor shun of han had not ended intrigue; it had simply shifted the stakes. Now, any move at court had to take into account not only the interests of the regent and factions, but also the slow maturing of the emperor himself, who would one day emerge from tutelage and demand his own say in affairs.

Life in the Capital: Luoyang Under a New Son of Heaven

While the highest echelons of power played out their silent dramas, the city of Luoyang breathed and bustled as it always had. For its inhabitants, the enthronement of emperor shun of han was at once distant and palpable. Distant, because most would never set eyes on their ruler, whose world was sealed within palace walls. Palpable, because imperial rituals, edicts, and the flows of money and grain from the state shaped the rhythms of their lives.

Luoyang was a city of contrast. Grand avenues lined with official residences cut across warrens of cramped alleyways where craftsmen, porters, and servants crowded into simple dwellings. On certain days, processions of carriages bearing high officials clattered past markets where street vendors shouted the prices of millet, fish, or silk remnants. Buddhist monks, still relatively new but gaining presence, moved among the more traditional temples and shrines, offering a different path to salvation that would one day spread across East Asia.

Under a new emperor, the city’s mood tilted toward cautious optimism. Rumors circulated that the accession would bring lighter punishments and new opportunities at court. Candidates flocked to the capital for examinations and audience, hoping that imperial favor might lift them and their families into comfortable office. Others fretted about the continuity of patronage networks: a change at the top could mean the loss of a patron and with it their position or protection.

For ordinary workers—porters unloading grain at the government warehouses, women weaving cloth in workshops tied to palace supply contracts, children running errands for officials—the change of emperor primarily meant new era names on documents, perhaps a brief remission of certain levies, and the intangible sense that history had moved one notch forward. Yet they, too, were stakeholders in the reign. Their labor sustained the court that taxed them. Whether the policies of emperor shun of han would make their lives harder or easier was not a theoretical question; it would be felt in the weight of their baskets and the emptiness or fullness of their bowls.

Frontiers on Fire: Qiang Uprisings and the Western Crisis

No sooner had Emperor Shun settled on the throne than the empire’s western marches demanded his attention. The Qiang peoples—pastoralist and semi-agricultural communities inhabiting the rugged lands of what is now Gansu and Qinghai—had long been both subjects and adversaries of the Han. For decades, mismanagement by local officials, heavy-handed attempts at resettlement, and the burden of corvée had fanned resentment. By the early second century, uprisings had become a grim routine.

During the Shun reign, these troubles flared dangerously. Posts in Liang Province were attacked, Chinese settlers fled their farms, and garrisons found themselves outnumbered and short on supplies. Military commanders urged urgent reinforcements; court economists warned of the enormous expense that sustained campaigns would entail. For emperor shun of han, still more symbol than strategist, these crises filtered through the lenses of reports, maps, and heated debates among his advisors.

The government’s response oscillated between conciliation and force. Some advocated granting Qiang leaders hereditary titles, integrating them more fully into the imperial hierarchy in exchange for cooperation. Others, steeped in traditional views of frontier management, pushed for punitive expeditions designed to crush resistance and reassert dominance. As usual, the reality on the ground was messier than the arguments at court allowed. In some places, Qiang and Han communities intermarried and traded; in others, raiding and reprisals perpetuated cycles of violence.

The cost of these conflicts was immense. Grain had to be shipped thousands of kilometers to sustain troops; weapons and armor had to be produced in abundance. The burden ultimately fell on taxpayers across the empire, whose labor financed distant wars they would never see. Each new requisition of supplies, each conscription of able-bodied men, tightened the pressure on communities already struggling with natural disasters and economic inequality.

From the perspective of historians, the frontier uprisings of this period were more than local disturbances. They were indicators of a state losing its grip on peripheries, stretching its resources thin for diminishing returns. The reign of emperor shun of han, haunted by these western crises, thus occupies a bittersweet place in the chronicles: a time when the center tried unsuccessfully to hold together a vast, increasingly unmanageable realm.

Scholars, Memorials, and the Moral Burden of Rule

If generals and governors managed the empire’s physical boundaries, scholar-officials attempted to police its moral ones. During Emperor Shun’s reign, memorials from upright Confucian literati poured into the capital. These carefully crafted essays criticized corruption, proposed policy changes, and invoked classical precedents to nudge the throne toward virtue.

The scholars’ relationship with emperor shun of han was complex. On one hand, they saw in him a potentially receptive audience: a young ruler with a reputation for mildness and a stated respect for the classics. On the other hand, they understood that real power remained tangled in the hands of regents, favorites, and eunuchs. Their memorials could be blocked, distorted, or filed away without action. Still they wrote, driven by a belief that to remain silent in the face of misrule was itself a moral failing.

Some of their concerns were concrete. They complained of overburdened peasants, of illegal land seizures by wealthy families, of officials who extorted bribes and manipulated the law. Others aimed at higher principles: they urged reductions in cruel punishments, argued for merit-based promotion, and warned that Heaven’s Mandate could be withdrawn if the government did not correct its course. As the Book of Han and later Hou Hanshu would emphasize, this tradition of critical counsel was considered integral to Han political culture, even if emperors did not always welcome it.

Emperor Shun, according to the annals, sometimes accepted such advice. He ordered investigations into particularly egregious cases of abuse, pardoned certain groups of accused individuals, and made gestures toward lightening the penal code. But his efforts were piecemeal, constrained by factional resistance and the inertia of a vast system. The moral burden of rule weighed on him; yet the tools available to lift it were blunt and often resisted by those whose power would be curtailed.

In this sense, the Shun reign became a stage on which the longstanding tension between Confucian ideals and political realities played out with particular clarity. The scholars held up a vision of humane governance, in which the emperor listened keenly to criticism and rectified abuses. The entrenched interests at court, meanwhile, worked to maintain their positions. The young ruler, sympathetic but limited, stood uncomfortably in between.

Inside the Palace Walls: Family, Consorts, and Silent Tragedies

Beyond edicts and military campaigns, there was another layer to Emperor Shun’s story: the intimate, often painful world of his family and consorts. Like all Han emperors, he was expected to take wives and concubines from prominent clans, weaving a web of alliances that reinforced the dynasty’s social and political foundations. Yet the inner palace was no haven of simple affection. It was a crucible where personal desires were subordinated to calculations of rank, fertility, and clan advantage.

One of the most poignant threads in this tapestry concerns his son, Liu Bing, the future Emperor Chong. Born to Consort Liang, he became the focus of intense hope: a child who would ensure the continuity of the line, a tangible sign that the dynasty’s future extended beyond Emperor Shun’s fragile body. But the lives of such children were perilous. Surrounded by jealousies, watched constantly by those who saw in them either opportunity or threat, their infancy and youth unfolded under pressures we can scarcely imagine.

The emperor’s relationship with his consorts was inevitably entangled with politics. A favored consort’s family might suddenly find itself elevated, its members appointed to coveted posts. A fall from favor, conversely, could doom entire lineages to obscurity or ruin. Every gesture of tenderness, every night spent in one woman’s quarters rather than another’s, could be read as a political signal. Under such conditions, sincerity itself became suspect.

Yet even in this hyper-charged atmosphere, human feelings persisted. We can imagine Emperor Shun of Han, in moments of exhaustion, seeking solace in quiet conversation with a trusted consort, sharing worries he could voice to no minister. Perhaps he spoke of omens that disturbed his sleep, of reports from the provinces that suggested growing unrest, of memorials that accused his own officials of terrible abuses. Perhaps he wondered whether his efforts, however earnest, could truly steer the empire away from the rocks he increasingly sensed ahead.

The palace, for all its grandeur, was also a cage. For emperor, consorts, and children alike, its walls confined as much as they protected. The silent tragedies that unfolded there—illnesses, miscarriages, early deaths, shattered hopes—rarely made it into the official record, which focused instead on lineage and titles. But they are part of the texture of the era: the human cost of carrying the immense expectations of empire.

The People’s Dynasty? Taxation, Famine, and Everyday Survival

From the vantage point of the throne, the empire appeared as a lattice of commanderies, counties, and households, each recorded in registers and summarized in reports. From the ground, it looked very different. For the vast majority of Emperor Shun’s subjects, life was defined not by the nuances of court factions, but by the weight of the tax grain on their backs and the reliability of the next harvest.

In theory, Eastern Han rulers—including emperor shun of han—upheld a paternalistic ideal: the emperor as father of the people, responsible for ensuring they had enough to eat, that taxes were moderate, and that justice, however imperfect, was not utterly absent. In practice, local realities varied wildly. In some regions, conscientious magistrates tried to shield their districts from the worst depredations, opening granaries in times of dearth, remitting certain labor obligations, and mediating disputes fairly. In others, predatory officials squeezed every last coin from the populace, aligning themselves with great landlords to amass fortunes.

The second century was not kind to the peasantry. Floods, droughts, and locust plagues periodically devastated crops. When natural disaster struck, the imperial government was expected to intervene—shipping grain, adjusting taxes, even relocating populations when necessary. Under Emperor Shun, such measures were sometimes taken, but the state’s capacity, drained by frontier wars and internal corruption, was limited. Many communities found themselves on their own.

The result was a slow but relentless process of dispossession. Smallholders unable to meet their tax obligations or repay debts sold their land to larger estate owners, becoming tenants on what had once been their own property. Others fled their registered homes, joining the swelling ranks of “drifters” who roamed in search of work or disappeared into marginal lands beyond effective official oversight. Scholars of later eras would point to this hollowing out of the free peasantry as a key factor in the Eastern Han’s eventual collapse.

Did Emperor Shun of Han understand the full extent of this suffering? Through reports, yes; through direct experience, almost certainly not. The distance between Luoyang’s polished floors and a farmer’s muddy field was not merely physical. It was epistemic, emotional. Yet the policies decided in those distant halls—tax rates, corvée requirements, war expenditures—translated immediately into hunger or relief for countless families. That is the cruel paradox of imperial governance: the more vast and impressive the system, the easier it becomes for the cries of individuals to be muffled by the rustle of documents.

Portents of Decline: Corruption, Eunuchs, and the Fracturing Court

As Emperor Shun’s reign advanced, the sense of a gathering storm intensified. The very mechanisms designed to support the throne—the bureaucracy, the palace service, the networks of noble clans—were increasingly captured by private interests. Corruption, always present in some degree, became endemic. Posts were bought and sold. Cases were decided not by law but by bribes and personal connections.

Eunuchs, whose access to the emperor gave them unique leverage, grew in both number and audacity. Some served honestly, mediating petitions and protecting the emperor’s privacy. Others exploited their positions ruthlessly, forming cliques, manipulating appointments, and amassing wealth. For scholar-officials committed to Confucian ideals, this trend was intolerable. They saw in it a direct affront to the hierarchical, morally grounded order envisioned in the classics.

The resulting tensions sometimes exploded into open conflict. Loyalist officials wrote scathing memorials denouncing particular eunuchs or powerful clans, fully aware that such outspokenness could cost them their careers—or their lives. The so-called “partisan prohibitions” that would later erupt, in which large numbers of scholars were banned from office for opposing eunuch abuses, had their seeds in this era of creeping authoritarianism and mutual suspicion.

Where was emperor shun of han in all this? The record suggests a ruler who was neither tyrant nor puppet, but a constrained monarch whose own temperament—inclined to kindness and caution—left him ill-equipped to crush entrenched corruption. He occasionally moved against notorious offenders, reasserting the law and trying to restore the appearance of just governance. Yet these actions were reactive and selective. The deeper structural problems—land concentration, the autonomy of great clans, the patronage webs binding eunuchs and officials—remained largely unaddressed.

To later historians, these years looked, in retrospect, like the prelude to catastrophe. But at the time, life went on. Omens appeared; memorials thundered; emperors aged and died. Only gradually, and unevenly, did the sense crystallize that the Eastern Han was not merely enduring a rough patch, but entering a phase of irreversible decline.

The Final Years of Emperor Shun of Han

By the 140s, emperor shun of han was no longer the wide-eyed boy pushed onto the throne, but a man in his thirties bearing the marks of long responsibility. His reign, extending over two decades, was one of the longer in Eastern Han history. Yet longevity did not translate into secure foundations. The same challenges that had haunted his accession—frontier unrest, internal corruption, social strain—lingered, sometimes flaring into open crisis.

In these final years, Shun took some steps to strengthen the center. He issued edicts condemning abuses by officials and, in certain celebrated cases, ordered severe punishments for those who had preyed on the people. He reaffirmed the importance of the classics in selecting and evaluating administrators, trying to realign the moral compass of the bureaucracy. Certain tax remissions and relief measures earned him local gratitude where they were effectively implemented.

Yet the limits of his power were painfully apparent. Attempts to curb great clans only pushed them to further entrench themselves in their home regions. Efforts to discipline eunuchs were met with quiet resistance and bureaucratic foot-dragging. Every policy the emperor proposed had to pass through a gauntlet of offices, each staffed by men with their own agendas and alliances.

On a personal level, Emperor Shun’s life bore its own scars. The death of beloved consorts, the burden of grooming heirs, the constant awareness that any illness could plunge the dynasty into another dangerous succession—these weighed on him as heavily as any memorial on statecraft. When his son Liu Bing was designated heir, Shun might have felt both relief and anxiety: relief that the lineage would continue, anxiety that a child was once more being placed in the line of fire.

In 144 CE, after roughly nineteen years on the throne, emperor shun of han died. The court dressed in mourning; proclamations of grief were issued; sacrifices were made. Official historians, tasked with appraising his life, would later describe him as benevolent but weak, a ruler whose good intentions collided with the stubborn realities of a decaying system. His posthumous name, Shun, affirmed the image of compliance and docility—an emperor who went along with the currents of his time more than he fundamentally redirected them.

With his passing, the empire did not collapse overnight. But the pillars he had tried, however imperfectly, to reinforce were already riddled with cracks that would soon widen under his successors.

Legacy of a Gentle Ruler in an Age of Gathering Storms

How should we judge Emperor Shun of Han? The question has haunted historians since the Hou Hanshu first set down its verdict, and later scholars like Fan Ye gave their own nuanced assessments. He was not a conqueror, not a reforming titan, not a philosopher-king whose sayings would echo through the ages. Nor was he a monster of cruelty or incompetence. Instead, he stands in the record as a figure of modest virtue, a man of mild disposition caught in a web of historical forces that exceeded his ability to command.

His accession in 125, so carefully engineered by Empress Dowager Deng and her allies, exemplifies both the resilience and the fragility of the Eastern Han system. On one hand, the dynasty managed a smooth transfer of power under dangerous conditions, avoiding the open civil wars that might have erupted. On the other hand, the very need for such manipulation revealed how far the throne had drifted from its ideal of sovereign autonomy.

Under his reign, the empire survived but did not fundamentally heal. Certain policies alleviated suffering; others unintentionally deepened structural imbalances. Shun’s cautious benevolence may have delayed greater upheavals by a few years, offering the people respite in particular regions and moments. Yet the broad trends—land concentration, bureaucratic corruption, frontier volatility—continued to erode the dynasty’s foundations.

And yet, there is something quietly compelling about his story. In a tradition that often celebrates the extraordinary—sage-kings, brilliant founders, ruthless unifiers—emperor shun of han represents a more ordinary, and perhaps more relatable, kind of ruler: one who tried to do good in less than ideal circumstances, whose failures were as much the product of systemic inertia as personal flaw. His life invites us to consider how much agency any one individual truly has when perched atop a complex, aging political order.

To see his legacy clearly is to look not only at court politics and military campaigns, but also at the ways later generations invoked his reign as a moral example or a warning. For some, he became a lamented figure—a “good man, bad time” archetype. For others, a symbol of the dangers of weakness in the face of corruption and factionalism. Both readings, in their different ways, kept his name alive in the long memory of Chinese political thought.

Echoes Through Time: How Later Generations Remembered Emperor Shun

Centuries after his death, Emperor Shun of Han lived on in books, debates, and quiet allusions. Confucian scholars of the Tang and Song dynasties, looking back over the rise and fall of countless regimes, often used the Eastern Han as a case study in the perils of decline. In their discussions, Shun appeared less as a central protagonist than as part of a tragic ensemble cast. Yet his reign was frequently singled out as one of the last moments when a relatively decent emperor still sat on an increasingly unstable throne.

Some later commentators, reading the Hou Hanshu, pointed to isolated acts of clemency and concern for the people as evidence that, given a different environment, emperor shun of han might have been remembered more positively. They saw in him a ruler who listened, at least intermittently, to remonstrating officials and who refrained from the more theatrical cruelties of some later emperors. For such readers, he offered a faint but real model of how personal virtue could persist even in an age of bureaucratic rot.

Others, more critical, argued that goodness without firmness was not enough. They contrasted Shun with vigorous reformers and military leaders of other eras, suggesting that his unwillingness or inability to smash corrupt networks had allowed them to deepen their hold. In this reading, his gentleness became indistinguishable from complicity, his reluctance to wield the sword of state a dereliction of duty. “The house was already on fire,” one later scholar paraphrased, “and he hesitated to break down doors for fear of disturbing the furniture.”

Modern historians, armed with archaeology, comparative analysis, and a more skeptical view of imperial ideology, tend to be kinder. They see his reign as part of a structural story: the maturation and overextension of a centralized agrarian empire, the rise of local elites, the limitations of early bureaucratic control. Within that frame, emperor shun of han appears less as a decisive agent than as a barometer of his time. His mild reforms and earnest gestures register the system’s lingering capacity for self-correction; their ultimate inadequacy reveals the depth of the crisis.

And yet, beyond scholarly verdicts, there is value in simply sitting with the human drama. A boy pulled into power before he was ready; a man aging under the weight of impossible expectations; a ruler who, in the end, could not prevent his dynasty from continuing its slow slide toward fragmentation and rebellion. His story is a reminder that history is not only made by great geniuses or villains, but also by those caught in the middle, doing the best they can with what they have, and leaving behind ambiguous, contested legacies.

Conclusion

The accession of Emperor Shun of Han in 125 CE was, on its surface, a triumph of continuity—a successful transfer of power in a sprawling empire that had already survived one great collapse and restoration. Beneath the ceremonial grandeur, however, lay a tangle of unresolved conflicts and structural weaknesses that no single individual, especially not a boy emperor, could untie. His reign unfolded as a fragile balancing act between ideal and reality, compassion and constraint, hope and slow disillusion.

Through his story, we glimpse an Eastern Han dynasty struggling to uphold the Mandate of Heaven in the face of frontier rebellions, bureaucratic corruption, and the steady erosion of its agrarian base. We see how regents, eunuchs, scholars, generals, and great clans all competed to shape policy, sometimes for the common good, often for private advantage. We also see the quieter worlds intersecting with his: the cloistered palace, the noisy markets of Luoyang, the wind-swept fields of distant provinces where peasants bent under taxed backs and watched the skies for omens of change.

Emperor Shun’s legacy resists simple labeling. He was neither a savior nor a destroyer of his dynasty, but a reflective, somewhat hesitant ruler whose personal virtues were outmatched by the historical forces arrayed around him. His accession marks a poignant moment when the possibility of renewal still flickered, even as the long arc of decline bent inexorably downward. To study his life is to confront the limits of individual agency in the face of entrenched systems—and to recognize, in that tension, a pattern that repeats throughout history.

In the end, the significance of emperor shun of han lies less in any single decree or battle than in the atmosphere of his times: an era of gathering storms, in which a well-meaning emperor presided over the slow unravelling of an imperial order. His story invites us to look beyond heroes and villains, and instead to ask how societies might respond when their institutions grow brittle, their elites self-serving, and their rulers, however sincere, are unable to stem the tide.

FAQs

- Who was Emperor Shun of Han?

Emperor Shun of Han, born Liu Bao, was an Eastern Han dynasty emperor who ascended the throne in 125 CE as a young boy and reigned until 144 CE. His rule is remembered for its relative benevolence but also for its inability to reverse the deepening structural problems of the empire. - How did Emperor Shun of Han come to the throne?

He became emperor following the death of Emperor An, after a carefully managed succession process dominated by Empress Dowager Deng Sui and her political allies. Liu Bao was selected because he was young enough to be guided yet old enough to command some respect, and his branch of the imperial clan was politically convenient to the ruling faction. - What were the main challenges during his reign?

His reign was marked by recurrent uprisings on the western frontiers, especially involving Qiang groups, growing corruption within the bureaucracy, the rising power of eunuchs, increasing dominance of great landlord clans, and mounting hardships for the peasantry due to taxes, war burdens, and natural disasters. - Was Emperor Shun of Han considered a good ruler?

Traditional histories portray him as benevolent and personally inclined to clemency, but politically weak. He made some efforts to reduce abuses and listen to remonstrating officials, yet failed to enact deep reforms. Modern historians often see him as a conscientious but constrained ruler operating within a decaying system. - How did his reign affect ordinary people?

For commoners, his reign meant continued tax and labor obligations, occasional relief measures, and the indirect impact of frontier wars and official corruption. While some imperial policies aimed to ease suffering, limited state resources and local abuses meant that many peasants experienced worsening economic pressure and land loss. - What role did Empress Dowager Deng play during his early reign?

Empress Dowager Deng Sui served as regent, effectively governing in his name during his minority. She controlled key appointments, balanced rival factions at court, and sought to maintain stability, making her one of the most powerful political figures of the early Shun era. - Why are frontier uprisings important for understanding his reign?

The Qiang uprisings and other frontier conflicts during his rule exposed the empire’s overstretched military and administrative resources. They consumed enormous amounts of grain and money, exacerbated tax burdens, and highlighted the weakening ability of the central government to integrate or control border populations. - How did later generations view Emperor Shun of Han?

Later scholars offered mixed assessments. Some saw him as a relatively humane ruler trapped in a bad era; others criticized him for not forcefully confronting corruption. Modern scholars typically interpret his reign as a revealing phase in the Eastern Han’s long decline, illustrating the limits of virtuous intent within a failing system.

External Resource

Internal Link

Other Resources

- Encyclopaedia Britannica – general search for the exact subject

- Google Scholar – academic search for the exact subject

- Internet Archive – digital library search for the exact subject