Table of Contents

- Dawn over Ulm: The World into Which Albert Einstein Was Born

- A Quiet House on Bahnhofstrasse: The Scene of an Unlikely Beginning

- The Einstein and Koch Families: Roots in a Changing German Landscape

- Germany in 1879: Empire, Industry, and the Age of Electricity

- The First Cry: Reconstructing the Day of Albert Einstein’s Birth

- Hermann and Pauline: Parents between Tradition and Modernity

- A Fragile Infant in a Hardened World: Myths and Realities of Einstein’s Early Health

- Ulm, Swabia, and Jewish Life in the Newly Unified Reich

- From Ulm to Munich: Why the Einstein Family Did Not Stay

- Childhood Echoes: How Early Surroundings Shaped a Restless Mind

- Electric Currents and Thought Experiments: The Family Business as a Silent Teacher

- The Broader Stage: Science, Empire, and the World Awaiting Young Albert

- Memory, Legend, and the Reconstruction of a Birth

- From Ulm to the Universe: Historical Consequences of a Single Life

- The House That Wasn’t Saved: Ulm’s War, Ruins, and Acts of Remembrance

- Einstein’s Own Reflections on Origins, Identity, and Belonging

- Why Birthplaces Matter: Historians, Monuments, and the Weight of Beginnings

- Conclusion

- FAQs

- External Resource

- Internal Link

Article Summary: On 14 March 1879, in the small city of Ulm on the River Danube, a child entered the world whose name would later reshape humanity’s understanding of space, time, and light: this is the story of albert einstein birth. This article follows the streets of nineteenth-century Ulm, the quiet Jewish household of Hermann and Pauline Einstein, and the newly forged German Empire to reconstruct the world into which he first opened his eyes. It traces the economic hopes and vulnerabilities that surrounded the family, and the social tensions that framed Jewish life in the Reich. Moving chronologically, it explores how the circumstances of albert einstein birth—his parents’ occupations, their moves, the technologies humming in the background—formed the subtle environment in which his mind grew. It examines how historians, biographers, and the city of Ulm have remembered and sometimes mythologized that beginning. The narrative also situates his birth within the broader currents of industrialization and scientific revolution that made his later achievements both possible and necessary. Along the way, it reflects on the emotional weight societies place on the first moments of a “great life,” asking what it really means to say that the universe changed on the day of albert einstein birth.

Dawn over Ulm: The World into Which Albert Einstein Was Born

On a chill March morning in 1879, the town of Ulm rose slowly to life beneath a pale Swabian sky. Smoke from new factories mingled with the older smell of wood fires, drifting between narrow streets and over the pointed roofs of houses that had watched centuries pass along the Danube. Church bells marked the hours, yet they now shared the soundscape with a more modern hum: workshops, railways, small electrical enterprises testing the boundaries of the possible. It was into this landscape of old stone and new steel that the event we now call albert einstein birth quietly unfolded, invisible to all but a few family members and midwives.

Ulm was no metropolis, but neither was it a sleepy backwater. It stood as a node in a rapidly industrializing Germany, newly unified under the Prussian crown less than a decade earlier. Soldiers in spiked Pickelhauben had marched home from the Franco-Prussian War; the iron rails of the railway stitched Ulm to Munich, Stuttgart, and beyond. In coffeehouses and beer halls, men argued about trade tariffs, about Bismarck’s political games, about the promise and perils of a powerful German Empire. Yet upstairs, above a modest shop on Bahnhofstrasse, a different drama was beginning—one that would, in time, defy every established idea of motion, light, and gravity that those same men took for granted.

Births are usually private affairs. The world rarely pauses, and that morning in Ulm was no exception. Barges creaked along the Danube. Apprentices swept wood shavings from workshop floors. Tailors adjusted their spectacles and continued their stitches. No newspaper recorded the arrival of the infant Albert Einstein, no official made a speech, no photograph captured the first exhausted smile of his mother, Pauline. Yet if we trace history backward—from the famous portraits of the wild-haired physicist to this modest house—we can almost feel the sheer improbability of it all: the way this quiet day would become a date whispered in documentaries, carved into plaques, and folded into every schoolchild’s image of genius.

But this was only the beginning. To understand the meaning of albert einstein birth, we must step into that house, into that family, into that empire—and then watch as the circles of consequence ripple outward across decades and continents.

A Quiet House on Bahnhofstrasse: The Scene of an Unlikely Beginning

The house where Albert Einstein was born no longer exists. This fact alone gives his birthplace an odd poignancy: the origin point of a life that would change physics has itself been erased by the very forces that transformed Europe—war, urban renewal, industrial modernity. Yet historians, armed with city records and family recollections, can still reconstruct the building that once stood at Bahnhofstrasse 20, a respectable yet unremarkable property near the railway station in Ulm.

The Einsteins did not own a grand villa. Hermann Einstein, the father, was a small businessman in the electrical trade, and the family’s home combined living quarters with commercial functions, as was common for the aspiring middle class. On the ground floor, there may have been a shop space or office connected with Hermann’s ventures in gas and electrical equipment. Above, on one of the upper floors, a set of rooms held the family’s modest furniture: a bedstead, simple wardrobes, perhaps a polished table that Pauline kept clean with the persistent care so often mentioned by later relatives.

It is here, in a bedroom likely heated by a small stove against the lingering cold of March, that we must imagine albert einstein birth. The city hospital was not the default venue for such events; most children of the German bourgeoisie were still born at home, assisted by midwives whose skills came from a mixture of formal training and long experience. In this room, linen sheets were laid out, water heated, and the tools of the midwife’s trade prepared. Outside, the clatter of carriages over cobblestones and the distant whistles of trains would have broken through the muffled sounds of labor.

We can infer much about the atmosphere from the social norms of the time. Childbirth was both feared and sanctified. Every family knew women who had suffered, even died, in those long hours between contractions. Jewish and Christian families alike might recite prayers, discreetly, under their breath. Even in relatively prosperous circles, anxiety about infection, hemorrhage, or a “weak” infant hovered like an invisible presence. Against this backdrop, the safe arrival of a living child was always a moment of cautious relief before it was a cause for celebration.

Later anecdotes describe the newborn Albert as a somewhat large-headed, unremarkably ordinary infant. One family story claims that his parents were initially alarmed by the shape of his head, which appeared misshapen or oversized, only to be reassured by doctors that the swelling would subside. It is astonishing, isn’t it, that the moment now mythologized as the birth of a genius was first filtered through such ordinary parental worry? The future theorist of relativity entered the world the way most of us do: fragile, wrinkled, and utterly dependent.

The Einstein and Koch Families: Roots in a Changing German Landscape

Albert’s arrival did not occur in a vacuum. The families into which he was born—Einstein on his father’s side, Koch on his mother’s—carried with them stories of migration, adaptation, and aspiration that mirrored the broader upheavals of nineteenth-century Central Europe. Understanding albert einstein birth means understanding these lineages that converged above a shop in Ulm.

The Einsteins were German Jews with Swabian roots. Hermann Einstein had been born in 1847 in Buchau, a small town in the Kingdom of Württemberg, at a time when Jews were gradually gaining civil rights yet still confronted entrenched prejudice. His father, Abraham Einstein, was a featherbed dealer, and like so many in that era his work combined commerce, travel, and negotiation across cultural lines. Hermann inherited both a sense of mobility and a willingness to take risks in new economic sectors—traits that would shape his son’s childhood.

On the other side stood the Koch family. Pauline Koch, Albert’s mother, came from a more prosperous background in Cannstatt, near Stuttgart. Her father, Julius Koch, was a successful grain merchant, and the family had, by the time of Pauline’s youth, secured a comfortable middle-class status. Pauline herself was well-educated for a woman of her time, with a noted love for music—particularly the piano—that she would later pass on to her son, sometimes sternly, sometimes as an offering of beauty amid financial anxieties.

The marriage of Hermann and Pauline was thus also a marriage of slightly different strata within the Jewish bourgeoisie: an ambitious, technically minded man and a cultured, musically inclined woman. This blend of practicality and aesthetic sensibility finds an uncanny echo in the adult Albert, who once remarked that if he were not a physicist, he might have been a musician. When historians sift through such parallels, they sometimes risk reading too much inevitability into the past. Yet it is difficult not to see, in this pairing, some of the early ingredients of his later character.

Socially, both families moved within the small but significant Jewish communities of southern Germany. Legal emancipation in the German lands had opened new professions and educational pathways, but doors did not swing open evenly for everyone. Restrictions lingered, and antisemitic attitudes persisted beneath the polished surface of bourgeois life. For families like the Einsteins and Kochs, education and technical skill were not just virtues—they were survival strategies. To thrive in a world that tolerated them uneasily, they had to excel. The child born in Ulm would grow up with this unspoken imperative surrounding him like air.

Germany in 1879: Empire, Industry, and the Age of Electricity

To truly grasp the significance of albert einstein birth, we must zoom out from the small house on Bahnhofstrasse to the sprawling map of the German Empire in 1879. This was a nation newly forged in war and iron. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 had ended with German troops entering Paris, and the proclamation of the German Kaiser in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. Under Otto von Bismarck’s Realpolitik, a patchwork of kingdoms, duchies, and free cities had been stitched into a single empire whose economic and military weight disturbed the balance of Europe.

In 1879, the empire was less than a decade old, but its transformative energy was unmistakable. Railways expanded, linking factory towns and ports in a dense web of steel. Coal output climbed, feeding blast furnaces and the dark lungs of locomotives. Urbanization accelerated as peasants left villages, their lives uprooted by mechanization in agriculture and the promise of wages in industrial centers. The hum of new technologies began to reshape not only landscapes but expectations: the assumption that progress—faster, brighter, more efficient—was the natural path of history.

One of the most striking innovations of the period was the rapid advance of electrical technology. The 1870s saw the emergence of practical dynamo machines for electricity generation, experiments in electric lighting, and the first public electrical installations. Germany, alongside Britain and the United States, pushed forward in what historians sometimes call the “second industrial revolution,” in which electricity and chemistry took center stage alongside steam and iron.

This matters for our story because Hermann Einstein was not simply a shopkeeper; he was involved in precisely this burgeoning field. With his brother Jakob, he later founded the electrical engineering company J. Einstein & Cie, which dealt in dynamos and lighting systems. The fact that albert einstein birth took place in the household of an aspiring electrical entrepreneur is more than a neat biographical detail. It placed the newborn, quite literally, in the currents of a technological transformation that would later inspire some of his most famous thought experiments about light, energy, and motion.

Politically, the year 1879 also marked a shift. Bismarck, concerned about economic competition, pressed for protective tariffs, signaling a turn toward more conservative, protectionist policies. Conflicts over culture and identity simmered: the Kulturkampf—a clash between the state and the Catholic Church—still echoed in provincial politics. And though the fiercest waves of modern antisemitism were yet to crest, early currents were already visible in public discourse, foreshadowing the darker chapters of German history that would intersect so tragically with Einstein’s later life.

Into this empire—industrializing, ambitious, restless—came a child whose later work would challenge the very foundations on which the age’s self-confidence rested: its faith in absolute time, immutable space, and mechanical predictability.

The First Cry: Reconstructing the Day of Albert Einstein’s Birth

What actually happened on 14 March 1879? We know the date with certainty, and the place—Ulm, in the Kingdom of Württemberg. Beyond that, details grow thin. Birth certificates do not describe expressions or weather. Family letters seldom dwell on the specifics of labor. Yet historians use the fragments we do have, alongside contextual knowledge, to build a plausible picture of the day on which albert einstein birth became a fact rather than a future biographical note.

Official records in Ulm give us the fundamental information: Albert was born to Hermann and Pauline Einstein, members of the Jewish community, living at Bahnhofstrasse 20. The date, 14 March, would later lend itself to numerological play (physics students like to note that π-day, 3/14 in the American notation, coincides with his birthday), but in 1879 it was simply a Friday in late winter. Temperatures in southern Germany that week hovered between cold and damp, with occasional snow, a minor hardship that would have weighed on those tasked with heating the house and fetching supplies for the birthing room.

We can assume Pauline was attended by at least one midwife, perhaps also by a doctor if complications were anticipated or if the family’s means permitted it. First births were always occasions for heightened concern. The testimony of later relatives suggests that the delivery was not unusually traumatic, but that initial alarm about the infant’s cranial shape darkened the first hours. As the story goes, Albert’s grandmother, seeing the newborn for the first time, is said to have exclaimed in dismay at his misshapen head, leading to a consultation with a physician who assured the family that the appearance was temporary. Whether this anecdote is precisely true or family folklore polished over time, it conveys the same essential truth: no one in that room saw a genius. They saw a vulnerable baby.

After the crisis of delivery passed, routine rituals would have followed. In a Jewish household, thoughts naturally turned to the upcoming brit milah, the circumcision ceremony traditionally held on the eighth day after birth, if the child was healthy. Names, in this context, were not casual choices. The name “Albert”—from the Germanic for “noble” and “bright”—was common enough, yet in retrospect it seems eerily apt. Alongside the religious customs, civil requirements demanded that the birth be registered with local authorities, adding the newborn to the administrative ledger of the state while family members considered his place in the lineage of ancestors.

There is little reason to imagine anything outwardly extraordinary about the day. The neighborhood proceeded with its commerce. Factory whistles signaled shifts. Newsboys cried the latest political debates and commercial announcements. Yet behind the walls of that modest house, a story began whose later chapters would be read in dozens of languages. The quiet ordinariness of albert einstein birth only deepens the drama of what came later.

Hermann and Pauline: Parents between Tradition and Modernity

Every birth is also the beginning of a relationship between child and parents. In the case of albert einstein birth, those parents stood at a crossroads between traditional Jewish life and the modern, technologically driven German middle class. Their own personalities and aspirations would leave indelible traces on the boy who grew up above their accounts ledgers and musical scores.

Hermann Einstein was not the stern, authoritarian patriarch sometimes conjured in caricatures of nineteenth-century fathers. Accounts portray him as gentle, somewhat quiet, and deeply invested in his entrepreneurial projects. He did not come from wealth, and his ventures into the electrical trade were bold steps into a volatile market. His willingness to adapt—to move to new cities, to change business models when necessary—shaped the geography of Albert’s childhood. Hermann’s failures, as much as his successes, would impress upon the young boy the instability of material security and the weight of financial risk.

Pauline, by contrast, emerges in recollections as a more forceful presence. She was devoted to order, education, and cultural refinement. Music was her passion, and she ensured that her children—Albert and, later, his sister Maja—received piano lessons. Albert’s own ambivalent relationship to the instrument, sometimes practicing with diligence, sometimes rebelling, unfolded under Pauline’s watchful gaze. Yet even his resistance taught him something about creative discipline and the tension between external rules and inner curiosity.

The couple’s approach to religion was likewise emblematic of their class and era. They maintained ties to the Jewish community, observed key rituals, and gave their son a basic Hebrew education. At the same time, they were far from strictly orthodox; their social world included non-Jewish neighbors and business associates, and they embraced much of the secular culture of the German bourgeoisie. This balance—rooted yet open, traditional yet modern—would later resonate in Albert’s own complex identity as a secular Jew who nonetheless spoke strongly about Jewish solidarity and ethical responsibility.

Financially, the family’s situation at the time of Albert’s birth was cautiously hopeful. The electrical industry promised growth, and Ulm, with its strategic location and emerging infrastructure, offered opportunities. Yet competition was fierce, and the long-term viability of Hermann’s early ventures was far from guaranteed. That fragility lay hidden beneath the baby’s cradle, a quiet rumble that would one day drive the family to leave Ulm behind.

A Fragile Infant in a Hardened World: Myths and Realities of Einstein’s Early Health

Over the decades, albert einstein birth has been surrounded by a halo of myths, many of them focused on his supposed oddities as an infant and child. Some stories claim he was slow to speak, others that he displayed early signs of extraordinary concentration, staring for hours at inanimate objects. Sorting truth from legend is not only a historian’s duty but a way of understanding how societies construct the figure of “genius.”

The most persistent myth is that Einstein did not speak until he was three or even four years old, a tale often used to comfort worried parents of late talkers. The truth appears more nuanced. Family recollections, recorded many years later, indicate that Albert began speaking later than average but not extraordinarily so, and that he sometimes repeated his own sentences softly to himself, as if testing their sound. This behavior, charming and slightly odd, later fed popular narratives that sought to locate his future brilliance in early signs of difference.

Medical accounts of his infancy are sparse. There is no evidence of severe illness in his first months of life, though childhood illnesses were common and often undocumented unless catastrophic. The anecdote about his large head, already mentioned, became emblematic in biographies: the infant whose brain would one day reimagine the cosmos seemingly signaled that destiny by the size of his skull. Yet this is almost certainly coincidence amplified by hindsight. Many newborns have temporarily swollen or oddly shaped heads due to the pressures of birth; most do not revolutionize physics.

The world into which the fragile baby arrived was far less forgiving than the one we know today. Infant mortality rates in the German Empire, while declining, remained high by modern standards. Infectious diseases lurked in every crowded street and poorly ventilated home. A simple fever could turn deadly. Parents, aware of these dangers, watched their children’s development with a mixture of hope and dread. In this context, Albert’s survival from infancy to childhood, though not unusual, was never guaranteed.

Later in life, Einstein himself rarely dwelled on his early physical development. He saw no drama in it worth recounting. That silence is telling. The transformation from vulnerable infant in Ulm to world-famous scientist in Princeton took decades and depended on countless contingencies. To compress that story into a handful of miraculous baby anecdotes is to miss the texture of growth, struggle, and chance that truly defined his path.

Ulm, Swabia, and Jewish Life in the Newly Unified Reich

Beyond the narrow frame of albert einstein birth lies the broader tapestry of Ulm’s cultural and religious landscape in the late nineteenth century. Ulm was a predominantly Protestant city with a strong Swabian identity: industrious, orderly, proud of its medieval past and its soaring Münster, whose great church spire dominated the skyline. Jews had lived in and around Swabia for centuries, sometimes tolerated, sometimes expelled, always negotiating their place among Christian majorities.

By 1879, legal emancipation had finally granted Jews in Württemberg and the rest of the German Empire equal civil rights on paper. They could attend universities, enter most professions, and participate in public life. In practice, however, social barriers persisted. Subtle exclusions in clubs, universities, and government offices reminded Jewish citizens that their belonging was conditional. Public discourse oscillated between celebration of Jewish contributions and resentment stoked by nationalist and antisemitic agitators.

The Jewish community in Ulm itself was relatively small but socially prominent enough to sustain a synagogue, community institutions, and professional networks. Families like the Einsteins found in this milieu a mixture of security and vulnerability. They could raise their children with a sense of both German and Jewish identity, attend respectable schools, and aspire to the cultural ideals of Bildung—the cultivation of mind and character that the bourgeoisie prized. Yet they could never entirely forget that, in moments of crisis, fault lines might reappear.

For the newborn Albert, these tensions were invisible, yet they surrounded him as invisibly as the air in the nursery. The conversations his parents had over dinner, the way they reacted to newspaper articles about politics, the choices they made regarding religious practice and social circles—all of these would have been shaped by the experience of being Jews in a young empire still defining what “German” truly meant. Decades later, when Einstein was forced into exile by a regime that defined “German” in racial terms explicitly excluding Jews, the irony would be bitter. His birth in Ulm, recorded in neat German bureaucratic script, was in one sense the first entry in a file that another German government would later seek to erase.

At the same time, Jewish life in Ulm and across southern Germany was vibrant. Synagogues hosted not only religious services but lectures and musical events. Jewish merchants, lawyers, and doctors participated in the economic modernization of their cities. The Einsteins’ involvement in electrical technology placed them squarely within this pattern of Jewish engagement with modernity: using scientific and technical knowledge as a bridge between minority status and full participation in the national project.

From Ulm to Munich: Why the Einstein Family Did Not Stay

For all the later significance attached to albert einstein birth in Ulm, the city itself played only a brief role in his life. When he was still an infant, the family left. This swift departure has sometimes puzzled admirers who imagine a deep, formative connection between Einstein and his birthplace. The explanation, however, lies in a familiar nineteenth-century story: the search for better economic prospects.

Hermann Einstein’s early business ventures in Ulm did not thrive as he had hoped. The electrical industry in its infancy was both promising and unstable. Contracts were uncertain, capital requirements high, and competition growing. Within a few years, it became clear that Ulm would not provide the springboard the family needed. Around 1880, the Einsteins moved to Munich, where Hermann and his brother Jakob founded “J. Einstein & Cie,” an electrical engineering company aiming to secure municipal and industrial contracts for lighting and power installations.

Thus, the boy who had taken his first breaths above a shop in Ulm would take his first steps, speak his first words, and attend his first schools in another city entirely. Munich, larger and more cosmopolitan than Ulm, exposed him to a different urban world: grand boulevards, art academies, scientific institutions, and, eventually, the demanding confines of the Luitpold Gymnasium, where his uneasy relationship with rigid schooling began.

Ulm, for the Einstein family, became less a home than a point on a migration map marked by risk and reinvention. In this, they were far from unique. Thousands of families in the German lands in that era followed the same pattern: leaving smaller towns for bigger cities, chasing industrial opportunities, packing up their belongings when ventures failed and hope flickered elsewhere. What distinguishes the Einsteins is not the fact of their movement but the later fame of the child they carried with them.

The briefness of Albert’s stay in Ulm complicates romantic notions of birthplace. If he retained any childhood memories of the city, they were likely faint impressions rather than vivid scenes. And yet the official record would always list Ulm as the location of albert einstein birth, tethering the city to his identity in ways that grew only more prominent as his reputation expanded. The irony is sharp: a city that did not shape his childhood significantly would one day build monuments and museums to celebrate the few months he spent within its boundaries.

Childhood Echoes: How Early Surroundings Shaped a Restless Mind

Although Ulm faded quickly from Albert’s direct experience, the circumstances of albert einstein birth and his earliest years reverberated through his development in subtler ways. The mixture of middle-class stability and entrepreneurial precarity, the fusion of Jewish heritage with secular German culture, and the constant presence of technical devices in the household formed a kind of cradle environment for his growing mind.

In Munich, visitors to the Einstein home later recalled the strange, mesmerizing presence of electrical apparatuses: dynamos, cables, and prototype lighting systems associated with J. Einstein & Cie. In one oft-told episode from his youth, Albert described the “wonder” he felt when his father showed him a simple compass. The mysterious force that guided the needle despite the absence of visible contact fascinated him. He later said that this experience left a “deep and lasting impression,” awakening his curiosity about invisible forces in nature. While the compass episode likely occurred in Munich rather than Ulm, its emotional power rests on the broader environment created by parents who took technology seriously.

The social milieu of the family also mattered. Educated conversation, respect for learning, and exposure to music and books were everyday realities. Albert’s uncle Jakob, involved in the family business, was mathematically inclined and helped introduce the boy to basic arithmetic and geometry beyond what school offered. This informal instruction, layered atop the disciplined musical training Pauline imposed, nurtured both analytical and aesthetic modes of thinking. The child who had once been an anxious subject of medical attention for his large head became a boy quietly working through geometry problems on his own, finding joy in the certainty of mathematical relations.

Even the family’s financial struggles, connected indirectly to the original gamble that had brought them to Ulm, left an imprint. When business contracts failed, when the Italian branch of the firm later collapsed, when debts forced sudden relocations, young Albert witnessed the fragility of adult plans. Stability, he learned, was not guaranteed, and authority could be fallible. This awareness, combined with a temperament suspicious of dogma, would eventually steer him to question not only teachers and priests but Newton himself.

Thus, while Einstein did not grow up amidst the medieval alleys of Ulm, the very forces that had drawn his parents there at the time of his birth—industry, technology, social mobility—continued to shape his inner world wherever the family moved. The cradle may have stood only briefly in Ulm, but the broader cradle of late nineteenth-century Central European modernity was far larger, and he never truly left it.

Electric Currents and Thought Experiments: The Family Business as a Silent Teacher

Many accounts of Einstein’s life jump quickly from albert einstein birth to his school years and then to his revolutionary papers of 1905. In doing so, they risk overlooking the formative role of a seemingly prosaic element: the family’s involvement with electricity. Long before he developed his famous thought experiments—chasing beams of light, riding trains through space-time—the child’s senses were exposed to the smell of ozone, the buzz of generators, and the warm glow of electric lamps.

Hermann’s and Jakob’s company installed electrical lighting systems in factories and public buildings, navigating the complex world of specifications, tenders, and technological standards. The talk at the dinner table, one imagines, often turned to voltage, current, client demands, and competing designs. It is not difficult to see how a boy growing up amid this conversation would absorb a feeling for electrical phenomena not as abstract textbook curiosities but as tangible parts of daily life.

Einstein himself, in later reminiscences, spoke of the power of “thought experiments”—mental scenarios in which he imagined physical situations and followed their logical consequences. These were not sterile mathematical games; they were vivid, sometimes almost childlike fantasies: imagining what the world would look like if one could ride on a light wave, or how clocks appeared to move when observed from different frames of reference. Such imaginative leaps require both abstraction and an intimate, almost tactile familiarity with physical processes.

Scholars have noted that the Germany of Einstein’s youth was saturated with the rhetoric of electricity as a symbol of modernity. Street lighting projects were unveiled with civic pride. Newspapers trumpeted the dawn of the electrical age. It is in this context that the family’s business activity, starting from their decision to settle in Ulm and then move to Munich, can be seen as an early, unintentional curriculum for the future physicist. Where other children might have seen only mysterious wires, young Albert glimpsed, perhaps, a field of forces waiting to be understood.

In a 1920s lecture, Einstein reflected on the transformation of physics since the days of Faraday and Maxwell, praising the conceptual unification of electricity, magnetism, and optics. Historians reading these lines often hear, beneath the formal gratitude to scientific predecessors, a more personal echo: the boy surrounded by electric devices, the adolescent pondering invisible fields, the adult deriving equations that would show how light, matter, and energy are intertwined. The chain that begins with albert einstein birth thus runs through the humming workshops of his father’s enterprises to the quiet rooms where he later wrote the equations of relativity.

The Broader Stage: Science, Empire, and the World Awaiting Young Albert

When Einstein was born in 1879, the scientific world was already humming with ideas that would pose challenges and offer clues to the work he would eventually undertake. Maxwell’s equations, unifying electricity and magnetism, had been published in the 1860s, laying the mathematical foundation for the electromagnetic theory of light. The Michelson–Morley experiment, which would famously fail to detect the ether wind and thereby unsettle assumptions about absolute space, lay just a few years in the future (1887). Thermodynamics, statistical mechanics, and the kinetic theory of gases were rich, controversial fields pushing the boundaries of understanding.

This scientific ferment unfolded within geopolitical structures that both enabled and restricted inquiry. The German Empire invested heavily in universities and research institutes, seeking prestige through scientific achievement as well as military might. Laboratories in Berlin, Göttingen, and other cities attracted brilliant minds; academic careers, though competitive and restricted by class and, increasingly, antisemitic discrimination, offered some men the chance to devote their lives to research.

Thus, the child whose first nights were spent in Ulm dozed beneath a sky already crisscrossed by invisible theoretical lines drawn by physicists and mathematicians. His future teachers would come from this world; the textbooks he studied would distill these debates; the conceptual puzzles arising from experimental anomalies—such as the behavior of light and the nature of energy—would form the backdrop against which his genius would later stand out.

At the same time, the empire around him was no quiet patron of pure thought. It was an aggressively nationalistic state, jockeying for colonies and economic dominance. Military technology and industrial innovation were tightly linked. The science that would eventually produce Einstein’s mass–energy equivalence, E = mc², was also the science that, in another context, would give birth to nuclear power and nuclear weapons. That tension—the simultaneous liberating and destructive potential of scientific progress—hung, unspoken, over the cradle in Ulm.

In a sense, then, albert einstein birth occurred at a crossroads not only of family histories but of intellectual and political histories. He entered a world where the old Newtonian clockwork universe still reigned in textbooks but was being quietly undermined in laboratories; where empires trusted in railways, telegraphs, and artillery to secure their power; where the question of what light really was—wave, particle, or something else—was more than a philosophical musing. The child would grow into the man who answered that question in ways that reshaped both science and the political uses to which science could be put.

Memory, Legend, and the Reconstruction of a Birth

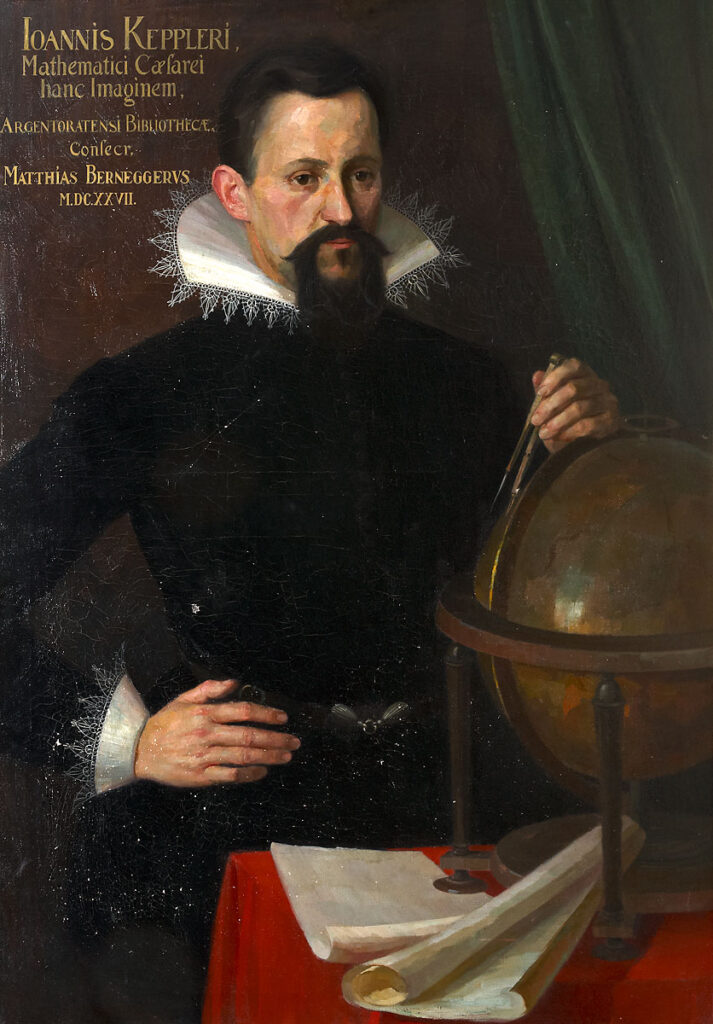

As Einstein’s fame grew in the twentieth century, albert einstein birth itself became a subject of curiosity and, inevitably, embellishment. Biographers scoured archives, interviewed surviving relatives, and compared notes in an effort to reconstruct not only the facts but the atmosphere of his earliest days. Yet the more one looks for drama in those first hours, the more one confronts the fundamental ordinariness of human beginnings.

One influential early biography by Philipp Frank, a physicist and friend of Einstein, emphasized the continuity between Einstein’s childhood curiosity and his mature scientific style. Another, by the journalist and science writer Walter Isaacson many decades later, leaned on family anecdotes to paint a picture of the young Albert as both dreamy and stubborn. In weaving their narratives, each writer treated albert einstein birth as a prologue, a symbolic curtain-raising on the life to come. The temptation to find “signs” of future greatness in every childhood oddity proved almost irresistible.

Yet serious historians caution against this teleological reading. As the historian Gerald Holton has argued in essays on Einstein’s life and work, it is all too easy to project backward a sense of inevitability that did not exist for those living through events in real time. Parents worried about their baby’s health did not know he would one day receive the Nobel Prize. Teachers exasperated by his rebelliousness could not imagine the global icon he would become. The birth recorded in Ulm’s registers was one among many that day, statistically indistinguishable from the city’s other additions to its population.

Still, the urge to commemorate and mythologize births is deeply human, especially when the later life has changed the world. Cities erect plaques; museums recreate rooms; tourists pose for photographs at “birth houses.” The absence of the original building in Ulm only intensified this impulse. In the postwar decades, as the city rebuilt itself from rubble, civic leaders and historians worked to locate precisely where Einstein had been born, to mark the spot, to inscribe on the urban fabric a memory of its most famous son—even if that son’s sojourn there was brief and his own feelings about nationalism complex.

Thus, the story of albert einstein birth is not only a story about what happened in 1879 but also about how later generations chose to remember, forget, or reimagine that moment. Every guidebook description, every school lesson that begins “Albert Einstein was born in Ulm…” participates in this ongoing construction of meaning. The bare fact of birth becomes a symbol: of genius emerging from modest origins, of Jewish contribution to German culture, of the unpredictable ways in which small lives can intersect with vast historical processes.

From Ulm to the Universe: Historical Consequences of a Single Life

If we trace the arc outward from albert einstein birth, the widening circles of consequence soon grow dizzying. A boy born in a modest house in Ulm becomes a student in Switzerland, a patent clerk in Bern, a professor in Berlin, an exile in Princeton. Along the way, he formulates the special and general theories of relativity, contributes crucially to the development of quantum theory, and becomes an international symbol of scientific creativity and moral conscience.

The scientific consequences are, in one sense, easiest to summarize. Special relativity (1905) abolished the notion of absolute time and space, showing that they are woven together in a four-dimensional space-time whose intervals depend on the motion of observers. General relativity (1915) then replaced Newton’s vision of gravity as a force with a geometric picture: matter and energy curve space-time, and free-falling objects follow the straightest possible paths within this curved geometry. These ideas, startling at first, proved extraordinarily successful, predicting phenomena such as the bending of light by gravity and the expansion of the universe—results confirmed by observation and experiment over the following century.

From these theories flowed technologies that now shape daily life: GPS systems, for instance, must account for relativistic time dilation to maintain accuracy. The very satellites circling Earth, whispering coordinates to smartphones, rely on corrections derived from equations written by the man whose first cry startled his family in Ulm. It is an almost surreal chain of causality, linking the intimacy of birth to the abstractions of tensor calculus and then back to the concrete reality of navigation in cars and planes.

There were, of course, political and ethical dimensions as well. Einstein’s public stance as a pacifist, his critique of nationalism, and his advocacy for Zionism and international cooperation made him a prominent voice in the turbulent decades of the early twentieth century. When Nazi antisemitism forced him to flee Germany in 1933, his emigration symbolized a catastrophic brain drain, the loss of a scientific culture that had once considered itself the jewel of Europe. His later involvement, however reluctant, in the chain of events leading to the Manhattan Project—most famously through his 1939 letter to President Roosevelt warning of the possibility of German atomic weapons—gave his name a shadowy connection to the nuclear age.

None of this, of course, was foreseeable on 14 March 1879. Yet the historian cannot help but glance backward, from mushroom clouds and GPS satellites, from gravitational wave observatories and black hole imaging projects, to the fragile infant in Ulm. The point is not to claim that everything followed inevitably from albert einstein birth, but rather to recognize how the unpredictable trajectories of individual lives intersect with the broader evolution of human knowledge and power.

The House That Wasn’t Saved: Ulm’s War, Ruins, and Acts of Remembrance

By the middle of the twentieth century, the physical space that had cradled albert einstein birth no longer existed. World War II turned many German cities into fields of rubble, and Ulm was no exception. Allied bombing raids in 1944 and 1945 devastated the city center. Amid the ruins, some structures were rebuilt, others cleared away to make room for new roads and modern buildings. The house at Bahnhofstrasse 20, already altered over the years, did not survive intact.

This loss has become part of the story. Visitors to Ulm today cannot enter a preserved “Einstein birth house” furnished with meticulous period detail. Instead, they find markers and plaques indicating where the building once stood, as well as exhibitions elsewhere in the city that commemorate his life and work. The absence of the original walls invites reflection: history, unlike architecture, cannot be rebuilt in brick and mortar, only reimagined through documents, memories, and narratives.

After the war, Ulm found itself in a Germany struggling with guilt, division, and reconstruction. Honoring Einstein, a Jewish scientist driven into exile by the Nazi regime, was both an act of civic pride and a gesture of atonement. The city named streets after him, supported educational initiatives, and worked with historians to clarify the details of his birth and the family’s short residence. In doing so, Ulm joined a broader pattern in postwar Germany of reclaiming Jewish contributions to national culture—contributions which the Nazis had tried to erase.

Yet behind the celebrations lay unresolved tensions. Some residents wondered whether the emphasis on albert einstein birth risked turning a complex life into a tourist brand. Others noted that honoring past Jewish figures did not automatically translate into welcoming contemporary Jewish communities. The politics of memory are rarely simple. Still, each plaque and exhibition stands as a small bulwark against forgetting, a reminder that the city’s most famous native son was not a general or politician but a scientist whose work transcended national borders.

In this way, the vanished house on Bahnhofstrasse 20 has become a kind of negative monument. Its physical absence forces us to confront the fragility of historical traces. All that remains are records, testimonies, and the determination of historians and local citizens to keep the story alive. For those who stand on the spot today, reading the inscription about albert einstein birth, the missing walls invite imagination: to picture the midwife, the anxious parents, the first cry, and the unimaginable future that rested, unknowing, in that small room.

Einstein’s Own Reflections on Origins, Identity, and Belonging

What did Einstein himself think about his origins? Surprisingly little, at least in public writings, focused on the specifics of albert einstein birth or his brief time in Ulm. Yet scattered through his letters and essays are reflections on identity, nationality, and the accidents of birth that shed light on how he understood his own place in the world.

Einstein often described himself as a “citizen of the world.” In a 1929 interview, he remarked, “Nationalism is an infantile disease. It is the measles of mankind.” For a man born in Ulm, educated in Switzerland, employed in Berlin, and exiled to the United States, national identity was indeed a shifting category. His German origins mattered—especially to those who claimed or rejected him as a symbol—but he wore them lightly. When asked about his biography, he sometimes responded with wry brevity, noting that the details of his early life were “not very interesting.”

At the same time, he took his Jewish identity seriously, particularly as antisemitism intensified in Europe. In a 1930 essay, he wrote, “My relationship to the Jewish people has become my strongest human tie, ever since I became fully aware of our precarious position among the nations of the world.” Here, the boy born into a relatively secure Jewish middle-class family in Ulm looked back across decades of mounting hostility to recognize the fragility that had always been there, even if it was not apparent in 1879.

Regarding his birthplace specifically, Einstein responded with grace when Ulm and other German cities sought to honor him in the 1920s and early 1930s. He accepted honorary citizenships and prizes, though he often used such occasions to speak not of personal glory but of the responsibilities of science and the dangers of militarism. After the rise of the Nazi regime, however, his relationship with Germany turned irrevocably sour. He resigned from the Prussian Academy, renounced his German citizenship, and eventually settled in the United States. Whatever sentimental attachment he had to the land of albert einstein birth was overshadowed by the horrors perpetrated in that land’s name.

Still, in moments of quieter reflection, he did not dismiss the role of early environment entirely. In letters to friends, he sometimes referred with affection to the landscapes and languages of his youth: the Swabian accent of his parents, the German songs of his childhood, the music his mother played. These were the textures of a life that began in Ulm and moved on, but never entirely left its first cultural coordinates behind. Even as he signed letters from Princeton with an American address, the registry in Ulm that recorded albert einstein birth maintained its quiet claim on his origins.

Why Birthplaces Matter: Historians, Monuments, and the Weight of Beginnings

Why do we care so much where a person was born? In the case of figures like Einstein, the fascination with origin can seem almost obsessive. Schoolbooks dutifully record “Ulm, 14 March 1879” next to his name. Tourists in Ulm seek out the markers of albert einstein birth as if proximity to that location might confer some insight into his genius. Historians, while more cautious, also devote significant attention to early years, searching for threads that lead from cradle to career.

Part of the answer lies in our narrative instincts. Stories need beginnings. To say “Einstein was born in Ulm” is to lay down a first point on a timeline, to orient the reader in space and time. That the place is a modest town rather than a famous capital adds to the drama: genius emerging from ordinary surroundings, the universal possibility that any unremarkable house might shelter the next transformative mind.

Another part comes from politics. Birthplaces can be claimed. Cities and nations eager for positive symbols latch onto the origins of great figures. Ulm’s embrace of albert einstein birth parallels Salzburg’s pride in Mozart, Pisa’s in Galileo, and Stratford-upon-Avon’s in Shakespeare. Such claims are not neutral; they feed tourism, civic identity, and, sometimes, nationalist myths. When Germany touts its scientific heritage, Einstein inevitably appears—despite the fact that the regime which drove him out would also have denied his Germanness.

For historians, the significance of birthplace is more subtle. It offers an entry point into socioeconomic context, cultural background, and the structures of opportunity that shaped an individual’s path. To study albert einstein birth is to study the German Empire at a particular moment, the status of Jews in Swabia, the rise of the electrical industry, and the everyday realities of middle-class life. The goal is not to draw a straight line from Ulm to relativity but to understand the web of conditions that made Einstein’s later achievements both possible and understandable.

Ultimately, perhaps, we return to the emotional dimension. Standing on the spot where a renowned life began allows us to feel, however briefly, the contingency of history. The thought that, had circumstances been slightly different—had Hermann’s business failed earlier, had illness struck, had migration taken another route—the name “Einstein” might have been lost in the anonymous dust of archival ledgers, is both humbling and strangely reassuring. The world we inhabit is built not only by the great but also by the countless unknowns whose births and deaths passed without plaques or biographies.

In this sense, albert einstein birth in Ulm is both singular and representative. Singular, because the life that followed was extraordinary. Representative, because the mechanisms of that birth—family decisions, economic pressures, cultural contexts—were shared by millions. Historians, standing between those two truths, try to honor both: the uniqueness of Einstein and the common humanity of the child he once was.

Conclusion

On 14 March 1879, in a modest house on Bahnhofstrasse in Ulm, an infant was born whose later work would change humanity’s understanding of the universe. At the time, albert einstein birth was a private event, marked by the usual anxieties and hopes that accompany any arrival into the world. His parents, Hermann and Pauline, stood at a crossroads of Jewish tradition and German modernity, their lives entangled with the rapid industrialization and social tensions of the new German Empire. The city around them, with its medieval spire and emerging factories, offered both opportunities and insecurities that would soon prompt the family to leave for Munich.

Reconstructing that birth and its context has allowed us to see how deeply Einstein’s life was rooted in the forces of his age: the rise of electricity, the shifting status of Jews in Central Europe, the ambitions of a nation determined to prove itself through science and industry. At the same time, attention to albert einstein birth cautions us against teleology. Nothing about the misshapen head that worried his family, the late-blooming speech, or the early fascinations with compasses and geometry guaranteed a future of Nobel Prizes and global fame. Only in retrospect do we draw connections that give shape to the story.

Yet this retrospective meaning-making is itself part of history. Ulm’s postwar commemorations, the debates of biographers, the visitors who seek out the site of the vanished house—all show how societies grapple with greatness and its origins. The absence of the original building has become a metaphor for the fragility of memory and the necessity of narrative. What persists are not walls but words: the registry entries, the recollections, the theories derived in faraway rooms by a man who once lay helpless in that Ulm bedroom.

In following the thread from albert einstein birth to black holes and GPS satellites, from a Jewish infant in the German Empire to a global icon in exile, we see history as a tapestry woven from contingency, context, and creativity. Birthplaces matter not because they predetermine destiny, but because they remind us that every world-changing mind begins in vulnerability, in a specific time and place, shaped by forces far beyond its control. To stand imaginatively in that room in Ulm is to feel both the weight and the lightness of beginnings—and to recognize, perhaps, the quiet, untold potential in every ordinary house where a new life has just begun.

FAQs

- Where and when was Albert Einstein born?

Albert Einstein was born on 14 March 1879 in the city of Ulm, in the Kingdom of Württemberg, part of the German Empire. His birth took place in a house at Bahnhofstrasse 20, a modest building near the railway station that no longer survives. - What do we know about the exact circumstances of albert einstein birth?

Surviving records confirm the date, place, and names of his parents, Hermann and Pauline Einstein. Biographical accounts suggest he was born at home, likely attended by a midwife, and that his family was briefly concerned about the unusually large shape of his head, which doctors reassured them would normalize. Beyond this, details are reconstructed from contextual knowledge of middle-class Jewish life in Ulm at the time. - Did Einstein spend much of his childhood in Ulm?

No. The Einstein family left Ulm when Albert was still an infant, moving to Munich around 1880 in search of better business opportunities in the electrical industry. His formative childhood memories and schooling are associated more with Munich, later Italy and Switzerland, than with Ulm itself. - Why is Ulm still considered important to Einstein’s story?

Despite his brief stay there, Ulm is the official site of albert einstein birth and thus holds symbolic significance as his point of origin. The city has embraced this connection through plaques, exhibitions, and public memory, using his birth to highlight its place in the history of science and to reflect on Germany’s complex relationship with its Jewish citizens. - Is Einstein’s birth house in Ulm still standing?

No. The original building at Bahnhofstrasse 20 was destroyed or heavily altered during World War II and subsequent urban redevelopment. Today, visitors can find markers indicating the approximate location and learn about the house through historical displays, but the original structure has not been preserved. - Did Einstein himself place much importance on his birthplace?

Einstein rarely spoke at length about his birth in Ulm and did not publicly romanticize it. He accepted honors from German cities, including Ulm, in the 1920s, but after the rise of the Nazi regime and his forced emigration, his relationship to Germany became strained. He tended to think of himself more as a “citizen of the world” than as a product of any single city. - How did the historical context of 1879 Germany influence his early life?

Albert was born into a newly unified, rapidly industrializing empire where electricity, railways, and heavy industry were transforming society. His father’s work in the electrical business placed the family at the heart of this transformation, exposing the young Einstein to technological devices and concepts that later resonated with his scientific interests. - Was Einstein really a late talker, and is that connected to his later genius?

Family recollections suggest he spoke somewhat later than average and had the habit of repeating sentences softly to himself, but there is no reliable evidence of an extreme delay. While popular stories link this to his later genius, historians caution that such connections are speculative and risk romanticizing what were likely ordinary developmental quirks. - What role did his Jewish background play from the very beginning?

From the moment of albert einstein birth, his life unfolded within the Jewish communities of southern Germany, which had recently gained civil rights but still faced social prejudice. His parents balanced religious traditions with secular education and participation in German bourgeois culture, shaping his identity as both Jewish and German—a dual belonging that would later be tested by rising antisemitism. - How do historians today view the significance of Einstein’s birth in Ulm?

Historians see his birth in Ulm as an important entry point into understanding his social, cultural, and economic background, rather than as a mystical origin of genius. It highlights the interplay between family migration, industrialization, Jewish emancipation, and educational opportunity that formed the environment in which his exceptional talents could develop.

External Resource

Internal Link

Other Resources

- Encyclopaedia Britannica – general search for the exact subject

- Google Scholar – academic search for the exact subject

- Internet Archive – digital library search for the exact subject