Table of Contents

- The Night the Bogside Erupted: August 12, 1969

- Seeds of Unrest: Northern Ireland’s Powder Keg

- The Bogside Community: A Portrait of Resilience and Frustration

- The Apprentice Boys Parade: A Trigger Amidst Tensions

- The Clash Begins: How a Parade Sparked a Riot

- The Role of the Royal Ulster Constabulary: Force and Fury

- The Formation of Free Derry: A Community Takes a Stand

- The Arrival of the British Army: From Peacekeepers to Participants

- Internment and Escalation: The Troubles Deepen

- The Broadening Conflict: Sectarian Divisions Harden

- International Reactions: Attention Turns to Northern Ireland

- The Human Cost of the Battle: Stories from the Frontlines

- Media and Memory: How the Battle Shaped Narratives

- Legacy of the Bogside: Political and Social Ripples

- The Battle in Cultural Imagination: Art, Literature, and Memory

- Reconciliation Efforts: Healing a Divided Community

- Lessons from the Bogside: Reflections on Conflict and Peace

- Conclusion: The Enduring Echoes of August 1969

- Frequently Asked Questions

- External Resource: Wikipedia Link

- Internal Link: Visit History Sphere

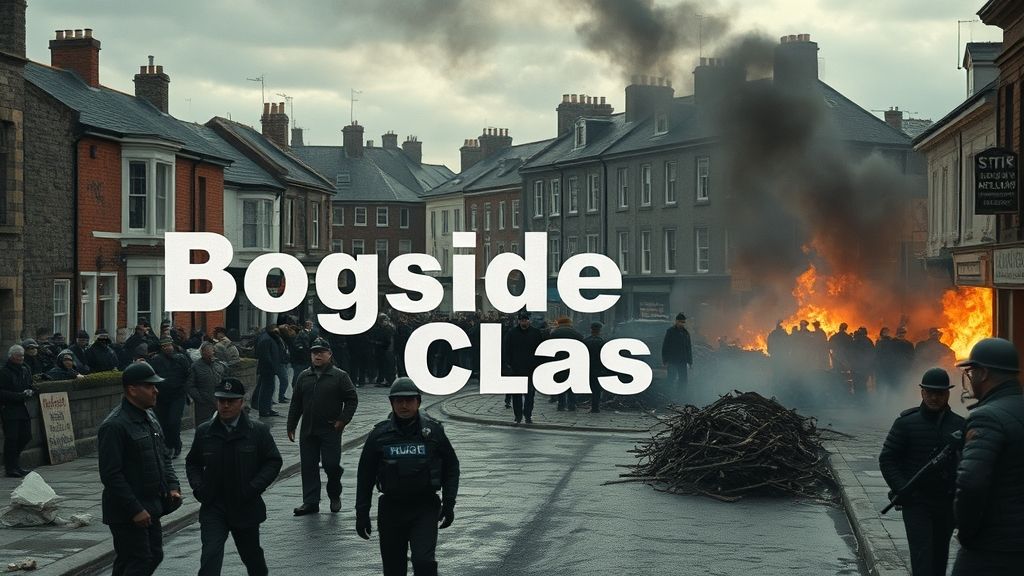

The Night the Bogside Erupted: August 12, 1969

The night was heavy with an ominous stillness, the summer air thick with acrid smoke and the ragged chants of a community on the brink. In the winding streets of the Bogside, Derry’s largest nationalist neighborhood, a powder keg lit—blackened tires blazed, stones flew like hailstones, and the sharp crack of gunfire echoed against red-brick walls stained with fear and defiance. August 12, 1969, was not just another summer night; it was the moment when simmering tensions exploded into the carnivalesque chaos that would mark the beginning of a brutal era known simply as The Troubles.

As barricades went up and the Royal Ulster Constabulary’s heavily armed lines clashed repeatedly with residents, the streets transformed into a battleground where identity, history, and survival intertwined. The Battle of the Bogside, as it would come to be known, was neither spontaneous accident nor mere riot; it was the culmination of long-festering grievances—a desperate cry from a community that had been sidelined for decades.

This was not just a local flare-up; it was a prelude to three decades of sectarian violence that would rend Northern Ireland and echo across the world. But to understand that night, one must first peer into the closely knit mosaic of politics, prejudice, and power struggles that fed the flames.

Seeds of Unrest: Northern Ireland’s Powder Keg

Northern Ireland in 1969 wasn’t a land of peaceful coexistence but a tinderbox stacked with decades of historical grievances and inequality. The roots of conflict burrowed deep into the soil of partition, a political decision forged in 1921 that created a Protestant-majority statelet within the six northeastern counties of Ireland.

The Unionist government, dominated by Protestants, held disproportionate power in every sphere of life—housing, employment, policing—while the Catholic minority, the nationalists, were marginalized systematically. Gerrymandering skewed electoral boundaries, ensuring Protestant control despite nationalist majorities in areas like Derry. Discrimination in housing led to overcrowded and substandard living conditions for Catholics, entrenching poverty and despair.

By the late 1960s, civil rights marches inspired by the American movement were gaining momentum, demanding reforms that challenged the status quo. The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) organized protests against electoral injustice, police brutality, and housing discrimination. What began as peaceful demonstrations faced violent responses — particularly from hardline loyalists and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), a police force seen by nationalists as a symbol of oppression.

The tension in Derry was palpable, a city split along invisible fault lines between nationalist and loyalist communities. The Bogside, a Catholic working-class enclave, embodied both hope and grievance—a place defined by resilience but scarred by systemic exclusion. August 1969 would bring these building pressures to a head.

The Bogside Community: A Portrait of Resilience and Frustration

The Bogside was more than a neighborhood: it was a tightly woven fabric of families, stories, and traditions. Generations of Catholics had lived here, trapped by economic stagnation but rich in cultural identity and political awareness. The community bore the brunt of discrimination—housing was cramped, jobs scarce, and opportunities systematically denied.

Yet beneath the surface of hardship was a simmering pride. Local activists, young and old, channeled their frustration into political awareness. Songs, murals, and stories recounted the history of an oppressed people yearning for equality. The sense of shared struggle created a profound solidarity, even as it seeded a fierce determination to resist injustice.

Tensions were inflamed further by the sectarian divide just across the city's “peace walls,” where Protestant loyalists celebrated their own identity with parades and flags. Nationalists often felt besieged, caught between a hostile security apparatus and encroaching敌意 from unionist neighbors.

The summer of 1969 saw an escalation in street violence, with frequent skirmishes between residents and the police. The Bogside was a tinderbox waiting for a spark.

The Apprentice Boys Parade: A Trigger Amidst Tensions

On August 12, 1969, the already fraught atmosphere in Derry became combustible as the Protestant fraternal order, the Apprentice Boys, marched through the city. The annual parade commemorated the 1689 Siege of Derry, a historical event deeply symbolic for unionists.

For many in the Bogside, the parade wasn’t just a cultural event—it was a provocation. The route passed perilously close to the nationalist neighborhood, and tensions had been mounting for days. Nationalists viewed the march as an assertion of dominance, a reminder of centuries-old grievances.

Police presence was heavy but ineffective at curbing escalating provocations. Stones were thrown, and minor scuffles erupted—yet none anticipated the level of violence the night would unleash. As the parade ended, what began as isolated confrontations spiraled into a full-scale battle between residents and the RUC.

The Clash Begins: How a Parade Sparked a Riot

The initial sparks of violence soon mushroomed into an intense conflict lasting three days. The Royal Ulster Constabulary attempted to disperse gathered crowds with batons and water cannons, but their tactics, perceived as brutal and indiscriminate, only inflamed passions.

Bogside residents responded with stone-throwing and improvised barricades made from burning tires, furniture, and debris, sealing off entry points into the neighborhood. For the first time in recent memory, a part of the city was effectively declared autonomous—“Free Derry” was born.

The sights were surreal: tear gas drifting over narrow lanes; children fleeing smoke and noise; shadows of armed men silhouetted against burning barricades. The sectarian undertones were unmistakable, as clashes intensified along ethno-political lines.

Though the police formally claimed to maintain order, their tactics alienated many nationalist citizens, who saw the force not as neutral enforcers but as aggressors. The battle exacerbated existing fault lines and deepened distrust that would fuel decades of violence.

The Role of the Royal Ulster Constabulary: Force and Fury

The Royal Ulster Constabulary was more than a police force—it was an institution entwined with unionist power. Its overwhelmingly Protestant membership was accused of collusion with loyalist groups and widespread discriminatory practices.

During the Bogside Battle, the RUC’s response to unrest was characterized by aggressive measures—armed patrols, baton charges, and indiscriminate use of force against protesters and innocent civilians alike. International observers would later condemn the handling of the riots as heavy-handed.

Statements by RUC officers revealed a belief they were maintaining essential order in a city descending into chaos—but their actions only deepened nationalist alienation. Rumors of collusion with loyalist militants fueled speculation of an orchestrated crackdown on the Catholic community.

This troubled relationship between the RUC and Catholic residents remained a continual source of friction throughout The Troubles, underscoring the charged nature of policing in a divided society.

The Formation of Free Derry: A Community Takes a Stand

Among the ashes and flames of conflict rose a powerful symbol of resistance: Free Derry. Days before, a local activist, John “Caker” Casey, painted the famous “You are now entering Free Derry” slogan on a gable wall as a declaration of self-governance.

The barricades which residents erected were more than defensive structures; they were a refusal to accept state control deemed illegitimate and oppressive. For many, Free Derry signified hope—a space where the community could assert their identity and autonomy.

Volunteer groups organized patrols to manage internal order, while external threats were warded off with makeshift weapons and sheer determination. The area became a no-go zone for the RUC, a radical claim seldom seen in modern Britain.

Yet Free Derry was also a fragile experiment, constrained by limited resources but buoyed by communal solidarity that defined much of the conflict’s grassroots dynamics.

The Arrival of the British Army: From Peacekeepers to Participants

Initially welcomed by many in the Bogside and wider nationalist community as a neutral peacekeeping force, British soldiers rolled into Derry later in August 1969, signaling a new phase in the conflict.

The British Army’s entry came aboard armored personnel carriers, an imposing presence claiming to restore order amid lawlessness. For some residents, soldiers represented hope for impartiality compared to the RUC; for others, an ominous sign of militarization.

But as time passed, British forces found themselves caught between opposing communities, sometimes accused of heavy-handed tactics that fueled further resentment. Incidents like Bloody Sunday in 1972 would mark a tragic turning point, but the seeds were already sown in the earlier confrontations of 1969.

The army’s ambiguous role—peacekeepers yet participants—would characterize much of the Troubles, complicating the narrative of victimhood and authority.

Internment and Escalation: The Troubles Deepen

The unrest sparked by the Battle of the Bogside triggered a cascade of political and security decisions that hardened The Troubles. In 1971, the British government introduced internment without trial, targeting suspected Irish republican activists.

The policy was deeply unpopular in nationalist areas and seen as a tool for mass repression. Thousands were arrested and detained under harsh conditions, further alienating Catholic communities and swelling the ranks of paramilitary organizations like the IRA.

Violence spiraled out of control: bombings, shootings, and sectarian killings became tragically commonplace. The Battle of the Bogside was the opening salvo in what became a complex and protracted conflict, with no easy solutions.

Northern Ireland was locked into decades of turmoil, with countless lives lost and communities torn asunder. To many, the events of August 1969 were a grim prophecy realized—an eruption that highlighted systemic failings and deep divisions.

The Broadening Conflict: Sectarian Divisions Harden

From a local spat in Derry, the Troubles evolved into a regional crisis. Sectarian identity hardened into weapons and ideologies fortified by generational resentments.

Loyalist paramilitary groups—Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and Ulster Defence Association (UDA)—launched retaliatory attacks against Catholic communities. Nationalist republicans escalated their armed campaigns against British state forces and unionist targets.

The city of Derry itself became emblematic of the conflict’s intractability: areas divided by “peace lines,” daily checkpoints, and constant fear. Ordinary citizens often bore the brunt, trapped in cycles of intimidation and violence.

Schools, workplaces, and homes became fragmented along sectarian lines, with social and economic opportunity suffering in the crossfire. The Battle of the Bogside was the spark that ignited these broader wounds.

International Reactions: Attention Turns to Northern Ireland

The images of burning tires and bloodied streets shone far beyond Northern Ireland’s borders. International media coverage introduced the broader public to a conflict widely ignored before the late 1960s.

Irish America rallied in support of nationalists, with fundraising, protests, and lobbying efforts aimed at hastening reforms or British withdrawal. The Irish government itself was pressurized to address the crisis, while London faced growing condemnation.

The United States Congress debated resolutions on Northern Ireland; the United Nations would occasionally weigh in, though with limited effect. The Troubles were no longer simply “local troubles” but part of a global conversation on colonialism, civil rights, and state violence.

Yet international responses often lacked effective intervention, leaving Northern Ireland trapped in a cycle of internal violence.

The Human Cost of the Battle: Stories from the Frontlines

Behind the headlines and political analysis were real people—children caught in crossfire, families displaced by arson, elderly residents too frightened to leave homes.

Jim McLaughlin, a Bogside resident, recalled ducking behind walls as tear gas drifted past while his mother tended to neighbors wounded by baton charges. Mary Kelly, a young mother, spoke quietly of losing friends to the violence and the sense that “no one was coming to rescue us.”

The Battle of the Bogside claimed dozens of injuries and destroyed homes, etching trauma into the community’s collective memory. The psychological scars lingered, feeding resentment and fear, but also a powerful sense of unity and identity amid adversity.

Personal testimonies etched the event into a narrative of resistance and endurance, the human soul wrestling with chaos.

Media and Memory: How the Battle Shaped Narratives

The Battle of the Bogside was among the first moments where television and photography brought the Troubles into living rooms worldwide. Dramatic images of burning barricades and confrontations framed public perceptions.

However, media coverage was often contested. Unionist outlets portrayed the RUC as overwhelmed heroes; nationalist papers decried police brutality and systemic oppression. These conflicting narratives entrenched polarization.

Over decades, the Battle became a touchstone for competing histories. The “Free Derry Corner” slogan turned into a pilgrimage site for some, while others viewed it as a monument to violence.

Memory politics—who tells the story, which version prevails—continues to reverberate in Northern Ireland’s delicate peace process and cultural debates.

Legacy of the Bogside: Political and Social Ripples

The battle marked the official ignition point of The Troubles. Politically, it spurred increased demands for civil rights and reform but also radicalized many.

It demonstrated the limits of policing in a deeply divided society and necessitated changes in governance and security tactics. The eventual suspension of Stormont government and direct rule from Westminster were partly responses to these crises.

Socially, the Battle reinforced segregation and mistrust but also galvanized movements for peace, reconciliation, and human rights advocacy.

Decades later, the Bogside still stands as a symbol—both of resistance against oppression and the price of communal violence.

The Battle in Cultural Imagination: Art, Literature, and Memory

Artists, writers, and musicians have long immortalized the Battle of the Bogside. Painters like Willie Doherty capture the haunting urban landscapes of conflict; writers such as Seamus Heaney referenced the violence and hope entwined in the era’s consciousness.

Murals dotting the Bogside preserve memories and narratives, making art a powerful tool for identity and storytelling. The battle also inspired films, documentaries, and music that blend history with emotion to reach new audiences.

Through culture, the trauma and tenacity of that summer night endure, inviting reflection on the costs of division and the desire for peace.

Reconciliation Efforts: Healing a Divided Community

Since the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, communities like the Bogside have embarked on painstaking journeys toward healing. Reconciliation projects address trauma, acknowledge past wrongs, and foster cross-community dialogue.

Initiatives focus on youth education, shared history programs, and memorialization efforts that seek to bridge historical divides rather than entrench them.

Yet challenges remain: deep-seated suspicions, political fracture, and unresolved grievances persist. The Battle’s legacy is a reminder of both the dangers of division and the possibilities of human connection.

Lessons from the Bogside: Reflections on Conflict and Peace

The Battle of the Bogside teaches lessons about identity, power, and the consequences of systemic injustice. When communities feel marginalized, when voices go unheard and grievances ignored, frustration can cascade into violence.

But the Battle also highlights the importance of solidarity, community resilience, and the enduring human spirit amidst adversity. It serves as a cautionary tale and a beacon guiding efforts toward understanding and reconciliation.

As Northern Ireland continues to navigate its complex history, the echoes of that August night remind us all of the fragile nature of peace and the labor it demands.

Conclusion

August 12, 1969, was more than a date—it was a crucible in which the hopes, fears, and fury of a divided society were violently melted together. The Battle of the Bogside was the thunderclap that startled the world and plunged Northern Ireland into a long night of conflict.

Yet, amid the smoke and ruins, there emerged a community that refused to be erased, that declared its own freedom even as the world turned away. The story of the Bogside is not only one of strife but of humanity stretched to its limits—of resilience, pain, and an unyielding search for justice.

Today, as Northern Ireland walks tentative steps toward peace, the memory of the Battle of the Bogside serves as both warning and inspiration. In those flames, we see the dangers of division but also the promise that from destruction, hope can rise anew.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What caused the Battle of the Bogside to erupt in August 1969?

The battle was triggered by the Apprentice Boys parade passing near the nationalist Bogside, coupled with long-standing discrimination and tensions between the Catholic minority and the Protestant-controlled state. Police aggression and loyalist provocations turned a volatile situation into violent riots.

2. Who were the main actors involved in the Battle of the Bogside?

The key actors included the Bogside residents—mainly Catholic nationalists—the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), Protestant loyalist groups, and later the British Army.

3. How did the Royal Ulster Constabulary influence the course of the battle?

The RUC’s heavy-handed and often brutal policing strategies alienated nationalist communities and escalated the violence, contributing to the creation of the self-declared autonomous zone known as Free Derry.

4. What was Free Derry?

Free Derry was a self-declared autonomous nationalist area within the Bogside neighborhood that operated independently of British state control during the clashes of 1969 and early 1970s.

5. How did the Battle of the Bogside affect the broader Northern Ireland conflict?

The battle marked the beginning of The Troubles, an extended period of sectarian conflict, paramilitary violence, and political upheaval in Northern Ireland that lasted for three decades.

6. What role did the British Army play after arriving in Derry?

Initially perceived as neutral peacekeepers, the British Army’s role became more complex and controversial, with some actions inflaming tensions further, leading to events such as Bloody Sunday.

7. What is the legacy of the Battle of the Bogside today?

The battle remains a powerful symbol of resistance, communal identity, and the costs of sectarian division. It informs ongoing peace and reconciliation efforts within Northern Ireland.

8. How is the Battle of the Bogside remembered culturally?

It is commemorated through murals, literature, music, and films that keep alive the memory and lessons of the event in Northern Irish society and beyond.