Table of Contents

- The Dawn of April 25th, 1974: A City Holding Its Breath

- Portugal under Estado Novo: Decades of Authoritarian Rule

- The Seeds of Discontent: Social and Economic Strains

- Salazar’s Legacy and the Rise of Marcelo Caetano

- The Colonial Wars: Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau

- The Armed Forces Movement: From Frustration to Rebellion

- The Conspirators in the Shadows: Planning a Silent Coup

- April 24th to 25th: The Night When Portugal Decided Its Fate

- Carnations and Rifles: The Peaceful Uprising

- António de Spínola’s Role: A General for Change

- The Fall of Estado Novo: Collapse of an Old Order

- The Euphoria of Freedom: Streets Filled with Hope

- International Reactions: A Cold War Puzzle

- The Immediate Aftermath: Revolutionary Councils and Political Flux

- The End of Colonialism: Rapid Decolonization and Its Challenges

- Cultural Renaissance: New Voices and New Freedoms

- The Transition to Democracy: Constitutions and Elections

- Economic Transformations: From Stagnation to Rebirth

- The Human Faces of Revolution: Stories from the Ground

- Myths and Memories: How the Carnation Revolution Lives Today

- Lessons from April 25th: Nonviolence and Change in the 20th Century

- The Revolution’s Legacy in Contemporary Portugal

- Carnation Revolution in Global Context: Echoes Beyond Borders

- Conclusion: A Quiet Revolution that Redrew a Nation

- FAQs: Understanding the Carnation Revolution

1. The Dawn of April 25th, 1974: A City Holding Its Breath

Lisbon awoke to a dawn heavy with the scent of anticipation, the faintest hint of gunfire intermingling with the spring air. The city’s morning light cast long shadows across cobblestone streets, where soldiers and civilians alike prepared for what was to become one of the most extraordinary peaceful revolutions of the 20th century. It was a Sunday like no other. The year was 1974, and Portugal’s Estado Novo—a regime that had ruled with iron resolve for nearly half a century—was about to be swept away, not by storm or bloodshed, but by the gentle bloom of carnations.

As the first notes of a clandestine song transmitted over the radio—“Grândola, Vila Morena” by Zeca Afonso—reached ears far and wide, a signal was given. Portugal, a country long shackled by authoritarianism, colonial wars, and economic isolation, was poised to change forever. It was a revolution unlike any other: led not by rallies, not by violent battles, but by the quiet courage of a small group of soldiers willing to risk everything for freedom.

2. Portugal under Estado Novo: Decades of Authoritarian Rule

To understand the magnitude of the Carnation Revolution, one must trace back to the establishment of the Estado Novo (New State) in 1933 under António de Oliveira Salazar. This corporatist authoritarian regime promised stability and order after years of political chaos and economic hardship in the early 20th century. Yet, that stability came at a steep cost: suppression of civil liberties, censorship, political repression, and a police state overseen by the feared PIDE (International and State Defense Police).

Salazar’s regime imposed a rigid social hierarchy and an economic model isolated from the tides of modernization sweeping through post-war Europe. The press was muzzled, political opposition crushed into silence, and education stifled to prevent critical thought. Portugal had become a country cloaked in shadows, where dissent was dangerous, and hope seemed dim.

3. The Seeds of Discontent: Social and Economic Strains

The veneer of hope offered by Estado Novo increasingly cracked under the strain of economic stagnation and the interminable colonial wars fought across Africa. By the 1970s, Portugal was one of Europe’s poorest countries, burdened by a sluggish industrial sector, low wages, and mass emigration. Young Portuguese men were drafted by the thousands into brutal wars in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau, deeply unpopular among the population.

The cost in human lives and economic resources created fractures within all layers of Portuguese society, from rural peasants to urban workers, intellectuals, and even parts of the military tired of fighting endless overseas conflicts that seemed futile and unjust.

4. Salazar’s Legacy and the Rise of Marcelo Caetano

Salazar’s stroke in 1968 marked the end of an era, as Marcelo Caetano took the helm, inheriting a faltering regime. Although Caetano was viewed by some as a potential reformer, his attempts at liberalization were cautious and ultimately superficial. The old structures held firm, and repression continued unabated.

The regime’s refusal to acknowledge the growing impatience among its citizens, coupled with its inability to end the drawn-out colonial wars, created an atmosphere simmering with unease. The Estado Novo was like a giant machine grinding relentlessly but showing clear signs of rust and corrosion.

5. The Colonial Wars: Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau

Perhaps no element defined the Estado Novo’s unraveling more than the colonial wars. From 1961 onwards, Portugal waged a protracted series of conflicts aimed at suppressing independence movements in its African colonies. The battles were brutal, costing thousands of lives and draining the country’s finances.

Soldiers fighting in harsh jungles far from home grew disillusioned quickly. The wars were seen by many as anachronistic and unjust. The weariness of combat, absence of clear military victories, and lack of support from broader society sowed the seeds for discontent within the armed forces.

6. The Armed Forces Movement: From Frustration to Rebellion

Among the critical actors catalyzing change was the Movimento das Forças Armadas (Armed Forces Movement, MFA), a clandestine group of progressive military officers determined to overthrow the regime and end the colonial war. Unlike many other revolutions across history, the MFA was not driven by a single charismatic leader but was rather a collective of junior officers who shared a vision of democracy and peace.

The MFA’s roots lay in frustration — frustration over pointless wars, oppression at home, and the lack of a political future for Portugal. It was this shared discontent that propelled them to plan in utmost secrecy the downfall of a regime that seemed invincible.

7. The Conspirators in the Shadows: Planning a Silent Coup

In the months leading up to April 25th, 1974, clandestine meetings took place in barracks, coffeehouses, and quiet neighborhoods of Lisbon and other cities. The conspirators understood that the success of their plans hinged on avoiding bloodshed and winning public support.

They orchestrated a calculated, nearly flawless operation, relying on coded radio broadcasts, coordinated troop movements, and the tacit approval of many civilians and some political groups who had suffered repression. The atmosphere was tense; any leak could mean massacre and imprisonment.

8. April 24th to 25th: The Night When Portugal Decided Its Fate

As night fell on April 24th, the streets were unusually quiet. The normal Sunday rhythm of Lisbon was disrupted by the hum of military vehicles and whispered orders. At precisely 10 p.m., a secret radio signal—the song “Grândola, Vila Morena”—blared on the airwaves, setting in motion the revolt.

Battalions began seizing key points: government buildings, communications centers, and military installations. Remarkably, there was almost no resistance. Many officers loyal to the regime were disarmed without violence, unwilling or unable to oppose their comrades.

The carnation, a simple red flower bought earlier by civilians and soldiers alike, was placed in the barrels of rifles as a symbol of peaceful change—an image that would be forever etched in history.

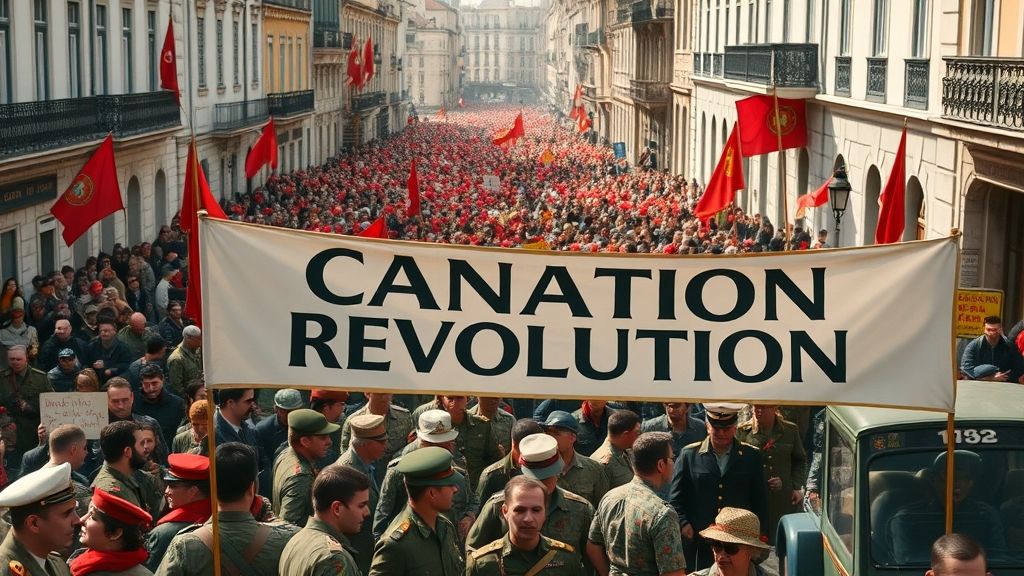

9. Carnations and Rifles: The Peaceful Uprising

What makes the Carnation Revolution truly extraordinary is its near-complete absence of bloodshed. Citizens flooded the streets, cheering the soldiers as liberators. Ordinary people handed out flowers, and resistance melted away before the tide of hope and unity.

This was not just a military coup: it was an uprising of conscience and spirit. The regime’s tanks, once symbols of oppression, became vessels of liberation adorned with blossoms. The quiet determination and the joy of a nation reclaiming its dignity radiated vibrantly through Lisbon’s plazas and alleys.

10. António de Spínola’s Role: A General for Change

General António de Spínola, a respected military figure, emerged swiftly as a key player following the coup. Though not part of the MFA’s inner circle, Spínola’s leadership was crucial in negotiating the regime’s surrender and guiding the transition.

His speeches urging calm and respect for democratic ideals helped channel the revolution’s momentum into a constructive political transition rather than chaos. Spínola symbolized a bridge between the old and new Portugal.

11. The Fall of Estado Novo: Collapse of an Old Order

By late April 25th, the Estado Novo had crumbled. President Marcelo Caetano was captured but accorded respectful treatment, signaling a deliberate move by the MFA and its supporters to avoid revenge and sow reconciliation.

The collapse was swift and dramatic, yet gentle compared to other revolutions—testament to the desire for change without destruction. The regime that had shaped Portugal for decades ended not with a bang, but with a hopeful chorus of birdsong and blossoms.

12. The Euphoria of Freedom: Streets Filled with Hope

In the days and weeks that followed, Lisbon and other Portuguese cities erupted in celebrations. People danced in the streets, sang banned songs, and embraced newfound freedoms. The joy was infectious, as if an invisible weight had been lifted from the nation’s collective shoulders.

Yet beneath the euphoria was an awareness of uncertainty. The path to democracy would not be smooth; old forces lingered, political factions jostled for power, and the challenge of decolonization loomed large.

13. International Reactions: A Cold War Puzzle

The Carnation Revolution occurred amidst the Cold War’s tense atmosphere. Western powers, particularly NATO members, watched nervously as Portugal—one of the few remaining authoritarian regimes aligned with the West—transformed.

Some feared a leftist takeover; others hoped for democratic renewal. The Soviet bloc saw an opportunity to expand influence. Yet the revolution’s uniquely peaceful nature confounded simplistic ideological readings.

14. The Immediate Aftermath: Revolutionary Councils and Political Flux

In the weeks after April 25th, revolutionary councils were established to govern cities and institutions. Political parties banned under Estado Novo returned from exile. Struggles ensued between moderate and radical factions.

Portugal plunged into a whirlwind of activism, strikes, and spirited debate as new visions for the nation were forged. It was a chaotic time, but it also birthed a vibrant democracy that would take root firmly in the years ahead.

15. The End of Colonialism: Rapid Decolonization and Its Challenges

One of the revolution’s most profound consequences was the swift end to Portugal’s colonial empire. Independence was granted to Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe within months.

However, this rapid blowout led to massive migrations, economic upheaval, and regional instability. Former colonies faced civil wars, and Portugal grappled with integrating tens of thousands of retornados (returnees) from Africa.

16. Cultural Renaissance: New Voices and New Freedoms

The Carnation Revolution ignited a cultural renaissance. Censorship was abolished, artists and writers flourished, and Portuguese society experienced a flowering of creativity.

Music, literature, theater, and cinema reflected the newfound openness and engaged boldly with Portugal’s history and identity. This cultural vitality persists today as a testament to the revolution’s enduring impact.

17. The Transition to Democracy: Constitutions and Elections

By 1976, Portugal had adopted a democratic constitution, laying a framework for political pluralism and human rights. Free elections brought a succession of civilian governments.

The transition, while complicated by ideological battles and social tensions, ultimately steered Portugal into the European democratic mainstream, culminating in its 1986 entry into the European Economic Community.

18. Economic Transformations: From Stagnation to Rebirth

Economically, the revolution and subsequent democratic governments faced the arduous task of modernizing a lagging economy damaged by years of authoritarian policies.

Structural reforms, investments, and European integration led to steady growth, rising living standards, and Portugal’s gradual emergence as a dynamic economy by the late 20th century.

19. The Human Faces of Revolution: Stories from the Ground

Beyond grand narratives stand the personal stories of hope, fear, and courage. Soldiers who risked everything, families who welcomed change, and ordinary citizens who dared to believe in a better future defined the revolution’s heart.

Tales of individuals placing carnations in rifles, shopkeepers opening doors to starving neighbors, and youths singing banned songs capture the human warmth behind political upheaval.

20. Myths and Memories: How the Carnation Revolution Lives Today

Over time, the Carnation Revolution has entered Portuguese collective memory as a symbol of peaceful resistance and democratic victory. Annual commemorations, monuments, and schools bearing its name keep alive the spirit of April 25th.

Yet debates continue about its complexities, the role of various political factions, and the unresolved legacies of colonialism and economic disparity.

21. Lessons from April 25th: Nonviolence and Change in the 20th Century

The revolution stands as a unique case in the 20th century’s turbulent history, demonstrating that authoritarian regimes can fall without violence if courage and strategy unite.

It serves as inspiration for movements worldwide seeking freedom through nonviolent means, underscoring the power of popular will and ethical dissent.

22. The Revolution’s Legacy in Contemporary Portugal

More than four decades later, Portugal’s democracy remains stable, and its society open and vibrant. While challenges persist, the foundations laid in 1974 continue to shape its politics, culture, and identity.

The Carnation Revolution remains a beacon, reminding Portuguese citizens of their collective strength and the fragile beauty of freedom.

23. Carnation Revolution in Global Context: Echoes Beyond Borders

Internationally, the Portuguese experiment contributed to the wave of democratization in Southern Europe—preceding Spain’s transition and influencing Latin American movements.

It challenged Cold War dogmas and illustrated that peaceful change was possible even under the repressive eye of authoritarianism.

24. Conclusion: A Quiet Revolution that Redrew a Nation

The story of the Carnation Revolution is the story of a nation’s awakening—a narrative of resilience, hope, and daring to dream of democracy after decades in the dark. It reminds us that revolutions need not be violent to be profound, that flowers can bloom amid rifles, and that courage often wears quiet smiles rather than bloodied banners.

Portugal’s April 25th stands as a luminous chapter in world history, inspiring all who believe in the peaceful pursuit of freedom.

Conclusion

Looking back on the Carnation Revolution, one is struck by the profound humanity that permeated even the most political of moments—a nation choosing peace over war, dialogue over bloodshed, and hope over despair. It was not merely a military coup, nor a spontaneous uprising, but the expression of a collective yearning for dignity, justice, and renewal. This revolution proves that even in the darkest of regimes, the light of change can be fostered by the quiet courage of ordinary people. Portugal’s peaceful overthrow of Estado Novo in 1974 remains a testament to the enduring human spirit and the timeless quest for freedom.

FAQs

Q1: What were the main causes of the Carnation Revolution?

A1: The revolution was driven by decades of authoritarian rule under Estado Novo, economic stagnation, unpopular colonial wars, and widespread social discontent—including frustrations within the military.

Q2: Who were the key figures behind the revolution?

A2: The Movimento das Forças Armadas (MFA), a group of junior military officers, planned and executed the uprising. General António de Spínola played a crucial leadership role in guiding the transition.

Q3: Why is it called the “Carnation Revolution”?

A3: On the day of the coup, civilians placed red carnations into the muzzles of soldiers’ rifles and on their uniforms, symbolizing peaceful change without bloodshed.

Q4: How did the revolution impact Portugal’s colonies?

A4: The revolution led to rapid decolonization and independence for African colonies, though this caused economic and political challenges both in Portugal and the newly independent states.

Q5: Was the Carnation Revolution violent?

A5: Remarkably, the revolution was almost entirely nonviolent, with virtually no casualties—a rarity among 20th-century revolutions.

Q6: How did the international community react?

A6: Reactions varied; Western nations were cautious due to Cold War tensions, while many hoped for Portugal’s democratization. The Soviet bloc viewed it as an opportunity.

Q7: What is the legacy of the Carnation Revolution today?

A7: It remains a symbol of peaceful transition to democracy and is commemorated annually in Portugal as a cornerstone of its modern identity.

Q8: How did the revolution influence other democratic movements?

A8: It inspired other countries to pursue nonviolent paths to democracy and showed that entrenched authoritarian regimes could be overthrown without widespread violence.