Table of Contents

- The Fateful Morning of December 23, 1876: A New Dawn in Istanbul

- The Ottoman Empire on the Brink: Turmoil and Transformation

- Sultan Abdul Hamid II and the Struggle for Absolute Power

- The Tanzimat Reforms: Seeds of Change and Unease

- The Young Ottomans: Intellectuals of Constitutionalism

- The Political Iceberg: Crisis and the Push for Reform

- Drafting the Kanûn-u Esâsî: The Birth of the Ottoman Constitution

- The Role of Foreign Powers: Encouragements and Threats

- The First Ottoman Parliament: Hope and Skepticism

- Reactions from the Provinces: From Constantinople to Cairo

- The Constitution’s Key Articles: Liberty Within Limits

- Press Freedoms and Political Clubs: Voices Awakened

- The Calamities That Followed: Conflict and Repression

- Abdul Hamid’s Suspicious Eye: From Sultan to Autocrat

- How the Constitution Changed Ottoman Society, Briefly

- The International Echo: How Europe Viewed the New Ottoman Order

- The Constitution’s Downfall: Suspension in 1878

- The Legacy of 1876: Seeds for Future Turkish Democracy

- Reflection on Empire and Reform: Lessons from the 19th Century

- Final Thoughts: A Moment of Hope Amid an Empire’s Twilight

The Fateful Morning of December 23, 1876: A New Dawn in Istanbul

As the sun rose over the ancient city of Istanbul, its golden rays glinted off the domes and minarets, casting long shadows upon the Bosphorus. On this December morning, the streets buzzed with an unprecedented energy—not from merchants or pilgrims, but from a populace waiting with bated breath for a proclamation that would forever alter the empire’s destiny. The Ottoman Constitution, known as the Kanûn-u Esâsî, was about to be declared, a monumental leap toward modern governance amidst an empire teetering on the precipice of collapse.

The atmosphere was electric yet fraught with uncertainty. Citizens from diverse cultures, languages, and faiths gathered in whispers and debates, aware that history was being made—but unsure whether it heralded salvation or simply masked impending turmoil. This constitution was not merely a legal text; it was a beacon of hope for reformers, a challenge to entrenched power, and a test for a multi-ethnic empire struggling to survive in a rapidly changing world.

The Ottoman Empire on the Brink: Turmoil and Transformation

The late nineteenth century found the Ottoman Empire grappling with relentless crises—military defeats, internal revolts, economic stagnation, and the ever-looming shadow of European imperial ambitions. Once a dominant Mediterranean power, this vast empire wrapped around three continents now seemed to be an aging giant, weighed down by antiquated institutions and fractured loyalties.

By the 1870s, the empire’s vast expanse—from Arabia to the Balkans—was rife with ethnic unrest and nationalist stirrings. The empire’s millet system, which had allowed a degree of religious autonomy, was strained under pressures for modernization and equality. Economically, the empire found itself in debt and dependent on European banks, while militarily, it faced humiliating setbacks against both internal insurgents and rival states.

Such conditions created fertile ground for reformist ideas. Calls for constitutional governance, legal equality, and civic participation grew louder among intellectual circles, bureaucrats, and frustrated elites. Yet, the empire’s complex mosaic of peoples—with Muslims, Christians, Jews, Turks, Arabs, Greeks, Armenians, Kurds, and others—made consensus elusive.

Sultan Abdul Hamid II and the Struggle for Absolute Power

When Abdul Hamid II ascended the throne earlier in the same year, he inherited a precarious realm. His rule began against a background of both hope and suspicion. Unlike some of his predecessors, Abdul Hamid was deeply shrewd and intensely wary of losing autocratic control.

Initially, he allowed the promise of reform to linger, balancing between conservative forces demanding the preservation of Islamic authority and liberal factions urging modernization. He had survived palace intrigues and political rivalries to claim the sultanate, but he keenly sensed that any loosening of his powers could undermine his rule.

His eventual endorsement of the constitution—the Kanûn-u Esâsî—was neither a full embrace of democracy nor a simple concession. It was a carefully calibrated act meant to quell growing unrest, placate foreign observers, and co-opt reformers while maintaining ultimate authority.

The Tanzimat Reforms: Seeds of Change and Unease

The proclamation of the constitution was the logical culmination of decades of reform known as the Tanzimat (Reorganization) era, which began in 1839 with the imperial edict of Gülhane. This ambitious program sought to modernize the empire—its military, administration, legal system, and society—inspired partly by European models.

The Tanzimat reforms introduced the notion that all Ottoman subjects deserved equal rights under the law, regardless of religion or ethnicity, a radical departure from centuries of privilege and customary rule. Schools, railways, and postal systems expanded; trade was encouraged; and bureaucratic centralization was strengthened.

However, these reforms also sowed tensions. Many conservative Muslims felt uneasy with these European-inspired changes, fearing the erosion of Islamic law and traditions. Non-Muslim minorities, meanwhile, had mixed responses—some welcomed equal treatment, others chafed under new taxation or bureaucratic interference. The empire was becoming a crucible of competing loyalties.

The Young Ottomans: Intellectuals of Constitutionalism

At the heart of the constitutional movement stood a vibrant group of reformers known as the Young Ottomans. These men—writers, politicians, and intellectuals—were inspired by liberal ideas, including constitutional monarchy, parliamentary governance, and civil rights.

Figures such as Namık Kemal and İbrahim Şinasi championed a blend of Islamic values with Western concepts of freedom and justice. They published newspapers, organized political societies, and agitated for limits on the sultan’s powers, arguing that despotism was the root cause of the empire’s woes.

Their advocacy faced brutal crackdowns, but their ideas endured and forced rulers—reluctantly—to consider some form of constitutional reform. The 1876 constitution embodied many of their aspirations, even if imperfectly applied.

The Political Iceberg: Crisis and the Push for Reform

The immediate context of the 1876 constitution’s proclamation was a confluence of crises. Military humiliations in the Balkans against rebellious Slavs and Serbs exposed the empire’s weaknesses. These defeats sparked uprisings and calls for autonomy, challenging the very notion of Ottoman territorial integrity.

The empire’s finances were in ruins after decades of debt and dependence on foreign loans, increasing European involvement in Ottoman affairs. Meanwhile, rumors of palace conspiracies and dissatisfaction among elites created pressure from within.

In this volatile environment, the newly formed Council of Ministers and reformist politicians saw constitutionalism as a necessary balm—and a way to internationalize the empire’s survival, showing Europe that the Ottomans could govern themselves under the rule of law.

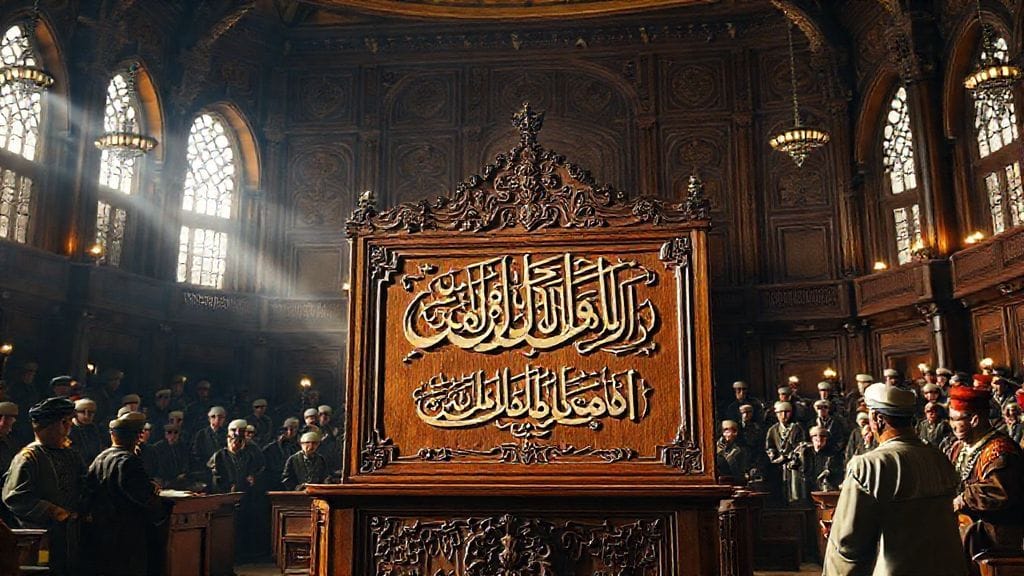

Drafting the Kanûn-u Esâsî: The Birth of the Ottoman Constitution

The Ottoman constitution, the Kanûn-u Esâsî (“Basic Law”), was drafted with urgency and a pragmatic approach. Taking inspiration from European constitutions—particularly the Belgian and French charters—it set out the structure for a bicameral parliament, established civil rights, and defined the limits of executive authority.

Despite being relatively short, the document was radical in the Ottoman context. It emphasized equality for all subjects, the principle of popular sovereignty, and regular elections. Yet it reserved significant powers for the sultan, including the right to dissolve parliament and veto legislation.

The constitution was ratified on December 23, 1876, in a ceremony as much political theater as legal formality, with Abdul Hamid II reluctantly affixing his approval. This event marked the transition from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy—at least on paper.

The Role of Foreign Powers: Encouragements and Threats

European powers—including Britain, France, and Russia—watched the Ottoman developments with intense interest. Their policies often oscillated between support for reform hoping to stabilize the empire, and designs to exploit its weaknesses for territorial gain.

Britain, for instance, saw a constitutional Ottoman Empire as a bulwark against Russian expansion toward the Mediterranean. Russia, conversely, encouraged Slavic uprisings to weaken Ottoman control.

Diplomatically, the proclamation of the constitution altered Ottoman relations. European powers pressured the sultan to uphold reforms and granted the empire breathing space from direct intervention—at least temporarily.

The First Ottoman Parliament: Hope and Skepticism

In early 1877, elections led to the first Ottoman Parliament convening in Istanbul, composed of a diverse assembly representing various ethnic and religious groups. The atmosphere was hopeful but tense.

Parliament debated laws on justice, education, and military reform, and for the first time, Ottoman citizens experienced a semblance of political participation. Journalists and political clubs flourished temporarily, encouraging lively public discourse.

Yet deep divisions existed: many parliamentarians remained loyal to the sultan, some distrusted the notion of Western-style governance, and others pushed for greater reforms. The challenge of uniting such disparate voices within an empire still rife with suspicion was immense.

Reactions from the Provinces: From Constantinople to Cairo

While Istanbul was the pulsating heart of reform, provincial reactions varied widely. In Cairo, the circumstantial autonomy under the Khedives led to ambivalent attitudes toward imperial reforms. Some elites welcomed modernization, while local nationalisms simmered beneath.

In the Balkans, nationalist ambitions overshadowed Ottoman constitutionalism. Many Slavic populations considered the reforms insufficient for their demands for independence or autonomy.

Arab provinces regarded the constitution with cautious curiosity, concerned about its impact on Islamic law and local governance. Across the empire, news traveled slowly, and skepticism often outweighed enthusiasm.

The Constitution’s Key Articles: Liberty Within Limits

The Kanûn-u Esâsî guaranteed several groundbreaking rights: freedom of religion, equality before the law, protection of property, and freedom of the press. It introduced the concept that sovereignty resided in the nation, not solely with the sultan.

However, these liberties were balanced by strong executive powers. The sultan retained command over the army, control of foreign policy, and could dismiss parliament at will. Islam remained the state religion and the shari’a (Islamic law) a reference for legislation.

In essence, the constitution attempted a delicate balancing act—modernizing governance while preserving the empire’s Islamic character and central authority.

Press Freedoms and Political Clubs: Voices Awakened

With constitutionalism came an unprecedented blossoming of the press and political activism. Newspapers, pamphlets, and journals addressed topics previously taboo: critiques of the government, discussions of liberalism, nationalism, and even socialism.

Political clubs formed in Istanbul and other cities—some secretive, others public—where citizens debated reforms and organized platforms. Young Ottomans and emerging intellectuals seized this new sphere to influence public opinion.

This era marked the beginning of Ottoman civic engagement and the public sphere, though it was not without limitations or repression when the regime felt threatened.

The Calamities That Followed: Conflict and Repression

Despite initial enthusiasm, the constitutional period was marred by wars and unrest. The Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878) devastated Ottoman armies, culminating in humiliating defeats and harsh peace terms that carved away Balkan territories.

Internal dissent continued unabated, as nationalist movements gained momentum. The government’s authority faltered, and fears of the empire’s disintegration grew.

Faced with these crises, Abdul Hamid II grew increasingly distrustful of the parliament and reformists, setting the stage for a darker turn.

Abdul Hamid’s Suspicious Eye: From Sultan to Autocrat

Within two years, Abdul Hamid II suspended the constitution and dissolved parliament in 1878, ushering in an era of autocratic rule lasting decades.

He implemented extensive censorship, secret police, and centralized control, suppressing political opposition and curbing freedoms granted by the Kanûn-u Esâsî. His reign became synonymous with “Hamidian absolutism,” balancing modernization with repression.

Yet, he retained the symbolic mantle of reformer and protector of Islam, positioning himself against foreign meddling—and asserting himself as the empire’s sole sovereign.

How the Constitution Changed Ottoman Society, Briefly

Though short-lived, the 1876 constitution left an indelible mark on Ottoman society. It introduced legal and political ideas that lingered in the public imagination and reformist circles.

It fueled debates on citizenship, identity, rights, and governance that carried into the twentieth century, influencing later constitutional experiments and the eventual birth of a republican Turkey.

Importantly, it exposed the tensions within the empire about modernity, tradition, and coexistence in a diverse society—a struggle that defined the Ottoman twilight.

The International Echo: How Europe Viewed the New Ottoman Order

Europe’s reaction was a mixture of hope and skepticism. Western liberal circles applauded Ottoman efforts to join the family of constitutional nations, while imperialists judged skeptically whether such reforms could survive.

The constitution temporarily improved the empire’s image, helping to delay more aggressive interventions. Yet powers like Russia and Austria-Hungary would continue to exploit Ottoman weakness at the first opportunity.

The Ottoman constitutional proclamation also inspired Muslim reformers elsewhere, offering a model—however flawed—of constitutional monarchy in an Islamic context.

The Constitution’s Downfall: Suspension in 1878

The swift suspension of the Kanûn-u Esâsî underscored the fragility of reform in an empire beset by internal and external crises. Abdul Hamid’s decision to dissolve parliament in 1878 demonstrated the limits of political liberalization when faced with war, nationalism, and imperial decline.

For two decades, the empire reverted to autocratic rule, but the ideals of constitutionalism never disappeared. They simmered beneath the surface, preserved in secret societies and intellectual debates.

In hindsight, the First Ottoman Constitution was less a failure and more a prologue to future struggles for democracy.

The Legacy of 1876: Seeds for Future Turkish Democracy

Though overshadowed by Abdul Hamid’s autocratic turn, the 1876 constitution planted crucial seeds that blossomed in the early twentieth century, culminating in the Young Turk Revolution of 1908.

This early constitutionalism created a vocabulary and legal framework that reformers could draw upon. It inspired generations to imagine a political community based on law, rights, and representative government.

Modern Turkey’s democratic aspirations trace parts of their lineage to this unique moment in Ottoman history, when hope briefly flickered in Istanbul’s winter chill.

Reflection on Empire and Reform: Lessons from the 19th Century

The story of the Ottoman constitution is a study in the challenges of reform within a multi-ethnic, multi-religious empire under pressure from external forces and internal contradictions.

It reveals how modernization and political change often provoke backlash, and how reform can be both a tool of survival and a threat to established power.

This episode invites reflection on the complexities of governance, identity, and the long struggle to reconcile tradition with change—a struggle as relevant today as it was in 1876.

Final Thoughts: A Moment of Hope Amid an Empire’s Twilight

The proclamation of the Ottoman Constitution on December 23, 1876, was more than a legal event—it was a moment of immense hope and profound uncertainty. It symbolized an empire’s desperate yet determined grasp for renewal and survival.

Though quickly overshadowed by autocracy and loss, this brief constitutional experiment ignited a flame of political awareness and civic aspiration that would eventually blaze into the fires of revolution and the birth of a new nation.

It stands as a poignant testament to human yearning for justice, representation, and dignity—universal ideals that transcend the centuries and the borders of empires.

Conclusion

The 1876 Ottoman Constitution represents an extraordinary chapter in the twilight years of one of history’s grandest empires. It was the product of turbulent times, a bold attempt to reconcile deeply entrenched imperial traditions with the pressing needs of modernization and political reform.

Though the constitution’s life was brief and Abdul Hamid II’s reactionary reign followed swiftly, the effort marked a critical departure point. It tested the possibilities and limits of constitutionalism in a deeply complex society and under immense external pressures.

The Kanûn-u Esâsî’s legacy lies not in immediate transformation but in the enduring ideals it embodied—constitutional government, equality before the law, and popular sovereignty. These ideals would continue to inspire reformers within the Ottoman domains and beyond, shaping the trajectory of the modern Middle East and Turkey.

Ultimately, this constitution speaks to the profound human desire to shape one’s destiny through law, community, and shared governance, even in the face of daunting odds. It reminds us that history is often a continuum of hope, struggle, and the quest for a more just political order.

FAQs

Q1: What prompted the Ottoman Empire to introduce a constitution in 1876?

A1: A combination of military defeats, internal unrest, pressures from reformist intellectuals and bureaucrats, and the desire to placate European powers pushing for modernization motivated the introduction of the 1876 constitution.

Q2: Who were the key figures behind the Ottoman constitutional movement?

A2: The Young Ottomans, including thinkers like Namık Kemal and İbrahim Şinasi, were pivotal, advocating for constitutional monarchy blending Islamic values with Western political ideas.

Q3: How much power did Sultan Abdul Hamid II retain under the constitution?

A3: Abdul Hamid II retained considerable power, including military control, the right to dissolve parliament, and veto authority, ensuring the constitution was a limited monarchy rather than a full democracy.

Q4: Why was the Ottoman Constitution suspended just two years after its proclamation?

A4: The empire’s military defeat in the Russo-Turkish War, internal divisions, nationalist uprisings, and the sultan’s mistrust of parliamentary power led to the constitution’s suspension in 1878.

Q5: Did the 1876 constitution influence later political developments in the Ottoman Empire?

A5: Yes, it laid foundational ideas and frameworks that inspired later reform movements, particularly the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 and ultimately the establishment of a constitutional republic.

Q6: How did non-Muslim communities within the empire react to the constitution?

A6: Reactions were mixed; some minorities welcomed legal equality and protections, while others remained skeptical about the implementation amid ongoing discrimination and nationalism.

Q7: What was the international community’s view of the Ottoman constitutional experiment?

A7: European powers viewed it with cautious optimism; it was seen as a step toward European-style governance that might stabilize the empire and protect their strategic interests.

Q8: In what ways did the 1876 constitution reflect both Western influence and Ottoman traditions?

A8: It blended Western constitutional structures like parliaments with Islamic principles and sultanic authority, aiming to modernize without wholly abandoning Ottoman-Islamic identity.