Table of Contents

- A Storm Gathers over Africa: The Eve of the Berlin Conference

- Europe’s Insatiable Appetite: The Scramble for Africa Begins

- Otto von Bismarck’s Gambit: The Architect of the Conference

- Calling the Powers: Who Entered the Arena?

- The Mapmakers and Diplomats: Participants and Their Motives

- The Conference Opens: November 15, 1884, Berlin in Tension

- The Rules of the Game: Establishing the Groundwork for Colonization

- The Principle of Effective Occupation: Justifying Empire

- Ignoring African Voices: The Silence of the Colonized

- Carving Up a Continent: The Partition of Africa Takes Shape

- The Impact on Indigenous Societies: Disruption and Resistance

- Global Ambitions and Rivalries: The Geopolitical Chessboard

- Economic Imperatives: Resources, Markets, and Industrial Hunger

- The Role of Missionaries and Explorers: Shaping Perceptions

- Violence and Coercion: The Reality Beyond Formal Agreements

- After the Conference: The Rapid Pace of Colonization

- The Long Shadow of Berlin: Legacies in Modern Africa

- Philosophical and Moral Debates: Imperialism’s Critics and Defenders

- African Responses: Early Nationalisms and Movements

- How Berlin Set the Stage for World War: Rivalries Intensify

- Reverberations Through the 20th Century: Decolonization and Borders

- The Conference in Historical Memory: Myths and Realities

- Lessons from 1884: Understanding Colonialism’s Origins Today

- Conclusion: The Berlin Conference’s Enduring Echo

- FAQs: Key Insights into the 1884 Berlin Conference

- External Resource: Wikipedia Link

- Internal Link: Visit History Sphere

A Storm Gathers over Africa: The Eve of the Berlin Conference

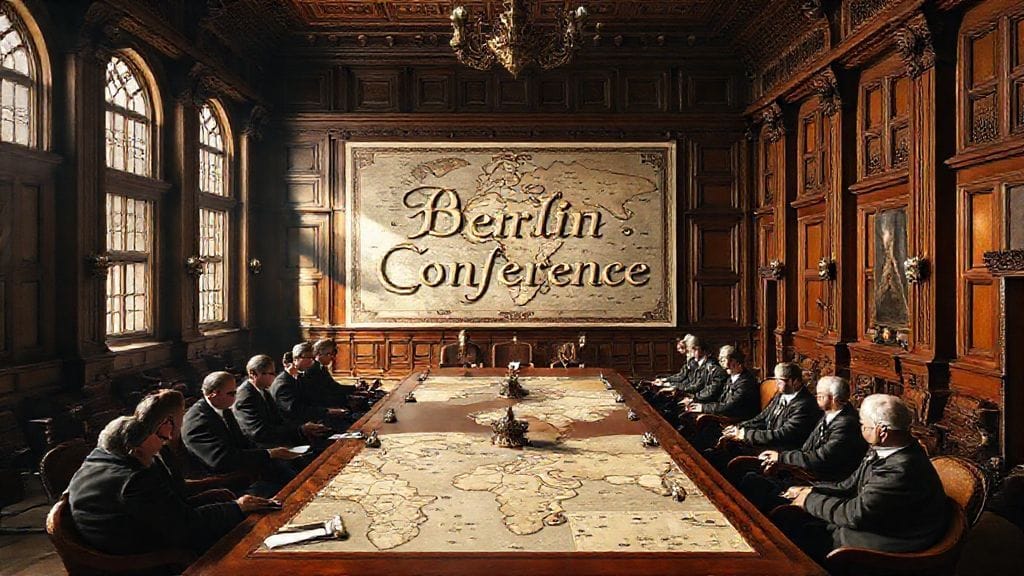

November 15, 1884. Berlin felt charged with an energy that was no mere diplomatic routine. Beneath the grey November sky, diplomats from Europe’s great powers gathered, their polished boots echoing in the packed halls of the Reich Chancellery. Outside, the city hummed with the mechanical rhythm of an empire at its peak, but inside, an invisible map was being redrawn—one that would change the fate of an entire continent forever.

Africa—vast, mysterious, and teeming with untapped riches—became the silent protagonist of this historic drama. The Berlin Conference was not just a meeting; it was the ignition of a global land rush that reverberates to this day. As flags were unfurled and voices rose in debate, the future of millions of Africans was sealed without their presence or consent.

Europe’s Insatiable Appetite: The Scramble for Africa Begins

During the late 19th century, Europe was gripped by an unprecedented wave of imperialistic fervor. Technological advancements—from steamships to the telegraph—pushed the limits of exploration, making Africa’s interior suddenly accessible. Coupled with industrial capitalism’s insatiable hunger for raw materials and new markets, Africa became the prize in a ruthless contest of power.

Nations like Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, Belgium, and Italy could no longer ignore their neighbors’ colonial acquisitions. Competition escalated rapidly, creating a volatile environment where land claims overlapped, alliances were fragile, and military expeditions raced against one another. The so-called “Dark Continent” was about to be plunged into a new kind of darkness—the dark shadow of imperialist partition.

Otto von Bismarck’s Gambit: The Architect of the Conference

Enter Otto von Bismarck, Prussia’s great statesman turned German Chancellor, a man known as the “Iron Chancellor” for his unyielding will and cunning political strategies. Although Germany was a latecomer to the overseas colonial race, Bismarck saw the conference as an opportunity to elevate his country’s status without plunging into costly wars.

Strategically, the Berlin Conference was Bismarck’s masterstroke—positioning Germany as a mediator in imperial affairs and setting rules that would serve European interests under the guise of order and civilization. However, Bismarck’s public rhetoric about “free trade” and “international cooperation” masked the aggressive scramble that would follow.

Calling the Powers: Who Entered the Arena?

The conference officially invited representatives from fourteen countries: European powers mentioned above, plus the United States and the Ottoman Empire, among others. Yet, it was the European players who dominated the stage.

Portugal clung desperately to its historic claims on the west and east coasts of Africa. Belgium, under King Leopold II, harbored more sinister plans in the Congo. Britain sought to connect its holdings from Cairo to Cape Town, realizing the dream that would become the “Cape to Cairo” vision. France eyed the Sahara and West Africa, while Germany claimed protectorates in Cameroon and Togoland.

Each delegate arrived with national ambitions tightly folded beneath official protocols—a recipe for tension and clandestine negotiations behind the gilded doors.

The Mapmakers and Diplomats: Participants and Their Motives

The attendees were a curious mix—diplomats skilled in negotiation, military officers with colonial experience, scientists, and businessmen. Men such as Jules Ferry from France, Paul Kruger representing the South African Republic in part, and Lord Granville from Britain wielded power not just in speech but in the silent calculus of empire.

Behind their diplomatic smiles laid deep-seated beliefs in European superiority, Social Darwinism, and the “civilizing mission.” Religious and humanitarian rhetoric would cloak these attitudes, justifying conquest as benevolent progress for Africa’s “backward” peoples.

The Conference Opens: November 15, 1884, Berlin in Tension

On that cold November day, the delegates took their seats in the spacious rooms of Berlin’s Reich Chancellery. The air was thick with cigar smoke and the murmur of languages—French, English, German—mixing in the stark chamber.

Bismarck’s opening speech set the tone: an appeal to reason and mutual respect, promising to temper rivalry with cooperation. His words projected a vision of partition as civilized order rather than ruthless grab.

Yet beneath the polished phrases, the undercurrent of urgency and competition was undeniable. The clock was ticking for those whose flags had not yet planted soil, for unclaimed regions could be swiftly lost.

The Rules of the Game: Establishing the Groundwork for Colonization

The conference established key principles that would govern how territories could be claimed. Notably, the “principle of effective occupation” was born: mere discovery or declaration was not enough. Powers had to demonstrate actual administration and control—through treaties with local rulers, police presence, or settlements.

The aim? To prevent conflicts over overlapping claims but also to encourage rapid expansion and dominance—thus accelerating the pace of colonial conquest.

Free trade zones were also agreed upon along major African rivers—the Congo and Niger—ostensibly to facilitate commerce and missionary work. Control of these arteries was critical for resource extraction and expansion.

The Principle of Effective Occupation: Justifying Empire

This legalistic requirement rationalized the brutal reality of conquest. If you wanted a piece of Africa, your flag alone was insufficient; boots on the ground were mandatory.

This principle incited a wave of expeditions, military campaigns, and the establishment of colonial administrations to hold territory. The scramble was no longer a vague claim but a tangible force, displacing indigenous authority and norms.

Ignoring African Voices: The Silence of the Colonized

Notably absent from the Berlin Conference were African leaders, voices, or representatives. The continent’s future was debated by outsiders, with no consideration of local governance, culture, or consent.

This exclusion encapsulates the paternalistic and imperial mindset—African peoples were viewed as subjects to be controlled rather than actors in their own destiny. This silence would sow seeds of resentment and resistance for generations.

Carving Up a Continent: The Partition of Africa Takes Shape

By the end of the conference in February 1885, borders and control zones had been roughly outlined. The map of Africa, previously undefined in European eyes, now shimmered with artificial lines—often straight and arbitrary, ignoring ethnic, linguistic, or cultural realities.

King Leopold II’s claim to the Congo Free State was internationally recognized, setting the stage for exploitation under a private monarchy. Britain secured vast stretches from Egypt to South Africa, while France claimed West and Central Africa. Germany’s holdings, though smaller, were a significant national achievement.

The “Scramble for Africa” was effectively sanctioned and legitimized.

The Impact on Indigenous Societies: Disruption and Resistance

For Africa’s peoples, partition meant upheaval. Societies with millennia-old traditions faced forced treaties, land seizures, conscriptions, and cultural denigration.

Some groups attempted cooperation or adaptation, others resisted fiercely. Famous uprisings, such as the Ashanti Wars and the Zulu resistance, revealed the cost of imperial ambition.

The imposition of foreign rule tore apart social fabrics and set conflicts that in some cases still echo today.

Global Ambitions and Rivalries: The Geopolitical Chessboard

The Berlin Conference was also a maneuver in the greater geopolitical game. Asia, the Americas, and Oceania might dominate European interest but Africa’s vastness and resources could no longer be ignored.

This new order generated rivalries extending beyond the continent—alliances hardened, and suspicions deepened, contributing to tensions that would culminate in the First World War.

Economic Imperatives: Resources, Markets, and Industrial Hunger

The industrial revolution demanded raw materials—rubber, gold, diamonds, palm oil—resources abundant in Africa. Colonies became suppliers and captive markets.

The economic exploitation was often underpinned by brutal labor regimes and neglect of local welfare, sowing economic patterns of dependency.

The Role of Missionaries and Explorers: Shaping Perceptions

Missionaries and explorers, like David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley, had paved the way for imperialism by mapping unknown lands and spreading European influence under religious cover.

Their stories excited European public opinion and provided both moral justification and practical information for conquest.

Violence and Coercion: The Reality Beyond Formal Agreements

Though the Berlin Conference framed colonization as lawful and orderly, the reality on the ground was often violent.

Military campaigns, forced labor, and massacres accompanied the expansion. The Congo Free State under Leopold stands as a ghastly example, with millions dying under his regime.

After the Conference: The Rapid Pace of Colonization

Following the conference, colonization accelerated dramatically. Within two decades, Africa’s political landscape was irrevocably altered.

The borders drawn laid the foundation for national boundaries still used today, fueling later struggles for independence.

The Long Shadow of Berlin: Legacies in Modern Africa

The conference’s impact endures. Arbitrary borders often sliced across ethnic groups, fostering long-term tensions. Colonial economies left patterns of extraction persisted after independence.

Yet African nations emerged resilient, developing identity and striving for self-determination despite these imposed fractures.

Philosophical and Moral Debates: Imperialism’s Critics and Defenders

At the time, critics such as Joseph Conrad or intellectuals raising concerns about imperial violence voiced opposition, though often marginally.

Conversely, many Europeans viewed empire as a noble mission—a belief that shaped policies and justified inequities.

African Responses: Early Nationalisms and Movements

Resistance evolved from armed conflict to political activism. Early nationalist figures began to challenge colonial rule, setting the stage for 20th-century independence movements.

How Berlin Set the Stage for World War: Rivalries Intensify

The scramble intensified European tensions, with collective suspicions over colonial ambitions contributing to the volatile alliances preceding World War I.

Reverberations Through the 20th Century: Decolonization and Borders

Post-World Wars, Africa’s independent states faced inherited challenges from Berlin’s partitions—identity conflicts, border disputes, and economic dependency.

The Conference in Historical Memory: Myths and Realities

Popular imagination sometimes overlooks the conference’s cold pragmatism behind the myth of “civilizing mission,” demanding nuanced understanding today.

Lessons from 1884: Understanding Colonialism’s Origins Today

Reflecting on Berlin enables a reckoning with the past and appreciation of Africa’s agency amid imposed domination.

Conclusion

The Berlin Conference of 1884 stands as a watershed moment in history—a cold calculus of European ambition imposed on an entire continent. It symbolizes both human capacity for order and injustice, planning and blindness.

Yet, amidst the sidelining of African voices and the brutality that followed, the resilience of African peoples shines through. Their histories did not begin or end in Berlin; they continue to unfold in the face of legacy and challenge.

Understanding this event is vital—not to dwell in regret—but to grasp how history shapes identity, power, and the quest for justice. The echoes of Berlin reverberate still, reminding us that imperial maps are never truly fixed, and that history’s story is always being rewritten.

FAQs

Q1: Why was the Berlin Conference convened in 1884?

A1: The conference was called primarily to regulate European colonization and trade in Africa, aiming to avoid conflicts among imperial powers amid intense competition over the continent.

Q2: Which major European powers participated in the conference?

A2: Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, Belgium, Italy, Spain, and others attended, along with non-European states like the United States and the Ottoman Empire, though the dominant role was European imperialists.

Q3: What was the “principle of effective occupation” established at the conference?

A3: It required powers to establish actual control over territories (administration, treaties, military presence) to claim sovereignty, discouraging mere nominal claims.

Q4: Were any African representatives present at the conference?

A4: No. Africans had no direct input or representation, reflecting colonial condescension and exclusion.

Q5: What were the immediate effects of the conference on Africa?

A5: The continent was partitioned with little regard for indigenous boundaries, leading to rapid colonization, social upheaval, and resource exploitation.

Q6: How did the Berlin Conference influence future global conflicts?

A6: It intensified rivalries among European powers, contributing to geopolitical tensions that helped spark World War I.

Q7: What lasting legacies did the Berlin Conference leave on Africa?

A7: Arbitrary borders, economic exploitation, and social disruption whose impact persists in political instability and identity conflicts.

Q8: How is the Berlin Conference remembered today?

A8: It is seen as a symbol of colonial imposition and the starting point for Africa’s modern history of colonialism, prompting ongoing reflection on imperialism and justice.