Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Scientific Context Before 1897

- Who Was J.J. Thomson?

- The Mysterious Cathode Rays

- The Experiment That Changed Everything

- Measuring the Electron’s Properties

- Overcoming Skepticism

- The Scientific and Philosophical Shock

- A New Atom: From Solid Sphere to Substructure

- The Plum Pudding Model

- How the Electron Redefined Chemistry

- Impacts on Quantum Mechanics

- Legacy in Technology and Society

- Conclusion

- External Resource

- Internal Link

1. Introduction

On April 30, 1897, a quiet revolution took place in the world of science. In a paper presented to the Royal Institution of Great Britain, Joseph John Thomson, a physics professor at Cambridge, unveiled a discovery that would shatter the indivisible atom. His experiments with cathode rays revealed a new particle—tiny, negatively charged, and universal—that we now know as the electron.

2. Scientific Context Before 1897

Throughout most of the 19th century, the atom was thought to be the smallest unit of matter, a solid, indivisible block, like billiard balls bouncing in space. Chemistry had advanced based on atomic weights and bonds, but the structure of the atom itself remained a mystery. It was untouchable, invisible, and assumed to be fundamental.

Meanwhile, strange phenomena were being observed in vacuum tubes—glows and rays that didn’t behave like anything else. These cathode rays became the focus of intense debate: were they waves or particles? Were they part of the atom, or something entirely new?

3. Who Was J.J. Thomson?

J.J. Thomson was born in 1856 in Cheetham Hill, Manchester. A brilliant student, he rose quickly through the academic ranks, becoming the director of the Cavendish Laboratory at just 28 years old. Known for his gentle demeanor and meticulous work, Thomson had a fascination with electrical phenomena and was determined to understand the nature of cathode rays.

He didn’t yet know he was about to discover the first subatomic particle.

4. The Mysterious Cathode Rays

Cathode rays were observed in glass vacuum tubes when high voltages were applied. They glowed, cast shadows, and caused certain materials to fluoresce. But what were they?

Some scientists argued they were waves in the ether. Others thought they might be atoms knocked loose by electrical currents. No one had a definitive answer.

Thomson’s approach was to measure—precisely and persistently—the behavior of these rays in magnetic and electric fields.

5. The Experiment That Changed Everything

Using a Crookes tube, Thomson subjected cathode rays to electric and magnetic fields. If the rays were neutral, they’d remain unaffected. But they deflected, just like charged particles.

Crucially, Thomson observed that the deflection suggested an extremely small mass—much smaller than any known atom—and a negative charge. This meant the rays were particles, not waves, and not atoms either. They were something inside atoms.

He calculated the charge-to-mass ratio (e/m) of these particles and found it to be far higher than hydrogen, the lightest known atom.

The inescapable conclusion? Atoms weren’t indivisible. They contained smaller components. The electron had been discovered.

6. Measuring the Electron’s Properties

Though Thomson didn’t yet isolate the electron or determine its exact mass, he opened the door for later scientists to do so. In 1909, Robert Millikan performed his famous oil drop experiment, measuring the elementary charge of the electron.

Together, these findings established the electron as a real, quantifiable entity—and the first truly subatomic particle.

7. Overcoming Skepticism

Thomson’s announcement was met with hesitation and disbelief. The atom was sacred; suggesting it could be broken down threatened decades of chemical and physical assumptions.

But Thomson’s work was meticulous and replicable. Within a few years, most of the scientific community accepted the existence of the electron.

This wasn’t just a particle—it was a paradigm shift.

8. The Scientific and Philosophical Shock

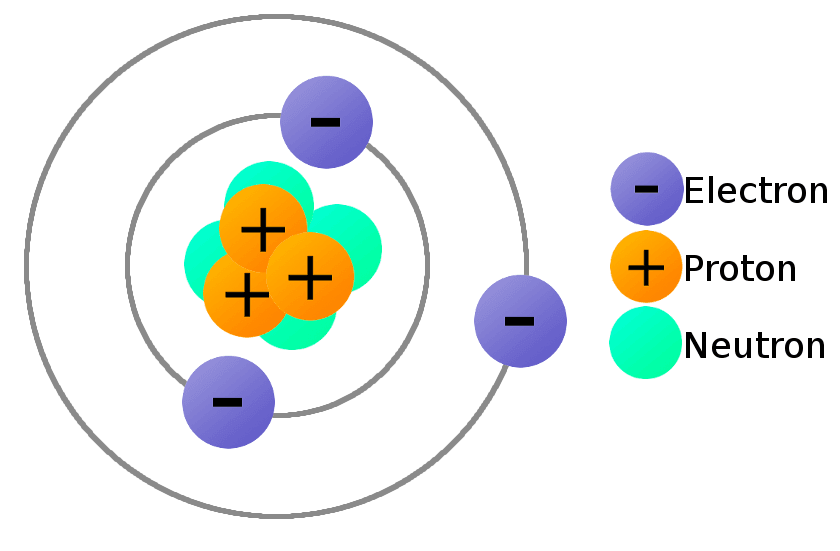

The discovery of the electron forced scientists to reimagine the atom. It was no longer a solid, indivisible unit—it had structure, internal parts, and electrical behavior. This realization shattered Newtonian simplicity and ushered in a new era of physics.

It also sparked philosophical debates. If the atom could be split, what else could lie beneath? Were protons and neutrons waiting to be discovered? What, then, was the nature of matter itself?

9. A New Atom: From Solid Sphere to Substructure

In response, Thomson proposed the Plum Pudding Model: the atom was a positively charged “pudding” embedded with negatively charged “plums” (electrons). Though later disproven, it was the first atomic model based on experimental data.

Later, Ernest Rutherford would revise this model using gold foil experiments, revealing a dense nucleus—but it was Thomson who cracked open the atomic shell.

10. The Plum Pudding Model

Though quaint by today’s standards, Thomson’s model offered a crucial stepping stone. It acknowledged internal structure and electrostatic balance. This idea was foundational for further models, including Bohr’s quantized atom and Schrödinger’s quantum cloud.

11. How the Electron Redefined Chemistry

The discovery of the electron revolutionized chemistry, too. Chemical bonds could now be understood as interactions between electrons. Reactions, ionization, and conductivity all became electron-driven concepts.

The periodic table became not just a list, but a map of electron configurations—and the basis for quantum chemistry.

12. Impacts on Quantum Mechanics

Electrons posed a problem for classical physics: they behaved like particles and waves. Their behavior couldn’t be explained using Newtonian laws.

This mystery led to the birth of quantum mechanics, with key contributions from de Broglie, Heisenberg, and Schrödinger. The electron became a symbol of duality, mystery, and the need for new mathematics.

13. Legacy in Technology and Society

Today, the electron is the backbone of technology. From electricity and semiconductors to computers and quantum computing, our modern world runs on electron manipulation.

- Electric circuits rely on electron flow.

- Transistors switch electron paths.

- Screens, LEDs, and lasers all use electron transitions.

- MRI, X-rays, and particle accelerators all depend on electron behavior.

J.J. Thomson’s quiet discovery now pulses through every microchip and mobile phone.

14. Conclusion

The discovery of the electron on April 30, 1897, was more than a scientific triumph. It marked the dawn of modern physics. It reshaped how we view matter, energy, and the atom itself. It shattered the illusion of indivisibility and opened the floodgates to quantum theory, relativity, and modern technology.

J.J. Thomson didn’t just discover a particle—he ignited a revolution that continues to power the world.

15. External Resource

![]() Wikipedia – Discovery of the Electron

Wikipedia – Discovery of the Electron