Table of Contents

- A Frozen Dawn at Canossa: The Penitence That Shook Christendom

- The Tumultuous Relationship Between Empire and Papacy

- Emperor Henry IV: The Man Who Challenged God

- Pope Gregory VII and the Reforming Zeal of the Gregorian Revolution

- The Investiture Controversy: Power Struggles Beyond Thrones

- The Road to Canossa: From Excommunication to Desperation

- January 1077: The Icy Walk of Henry IV

- The Three Days in the Snow: Waiting at the Castle of Canossa

- The Moment of Reconciliation: Between Forgiveness and Politics

- The Symbolism of the Penance: Humility or Strategic Submission?

- Reactions in Europe: Chronicles, Rumors, and Propaganda

- The Aftermath: Did the Pope Really Triumph?

- The Long Shadow of Canossa on Medieval Power Dynamics

- The Mythologizing of Canossa in Later Centuries

- Canossa and the Making of Modern Church-State Relations

- Personal Reflections: Henry IV and Gregory VII Beyond History

- The Architectural Legacy of Canossa Castle

- Parallels in History: When Pride Meets Penitence

- The Role of Memory and Historical Narrative in Shaping Canossa

- Conclusion: A Moment Frozen in Ice and Time

- FAQs: Exploring the Intricacies of the Canossa Penance

- External Resource

- Internal Link

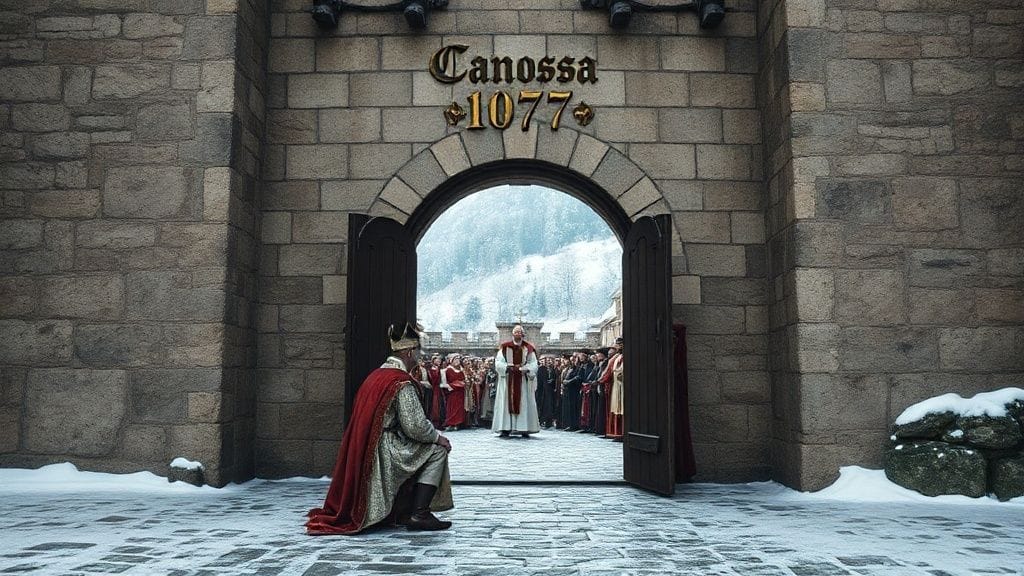

1. A Frozen Dawn at Canossa: The Penitence That Shook Christendom

It was January 1077, somewhere on the snow-covered slopes of the Apennines, where a medieval emperor, cloaked in simple sackcloth, stood barefoot in the biting cold, waiting humbly outside a fortress. For three days, Henry IV churchman and monarch awaited the merciful gaze of the Pope he had defied—and the whole world watched in anticipation and disbelief. The scene at Canossa was anything but ordinary. It was a dramatic tableau of faith, power, humiliation, and political theatre set against a harsh winter backdrop that would echo through centuries. This event—the penitence of Henry IV before Pope Gregory VII—is one of medieval Europe’s most riveting moments, a turning point in the tumultuous dance between secular and spiritual authorities.

It was not mere humiliation; it was an unprecedented public act laden with symbolism, where a king submitted to the authority of a pope, altering the landscape of European governance forever. But beneath the surface of this icy encounter lay complex forces—ambitions, faith, rebellion, and survival. To understand why an emperor stooped to this act requires diving deep into the heart of medieval Europe’s most volatile conflict.

2. The Tumultuous Relationship Between Empire and Papacy

The 11th century was a crucible of change and tension between the Church and secular rulers. The Holy Roman Empire, founded by Charlemagne and a legacy of the Roman Empire's eastern continuation, saw itself as the pinnacle of earthly authority. Yet, the papacy—anchored in Rome, the spiritual heart of Christendom—claimed supremacy that threatened imperial sovereignty.

At this time, the Church sought reform, aiming to purify its ranks and reassert spiritual independence. The Investiture Controversy, the bitter quarrel over who had the right to appoint bishops and church officials, became the battlefield where these claims clashed. Kings and emperors appointed bishops, not only as spiritual leaders but as territorial rulers, making the investiture a question of political domination as much as religious control.

Amid this fraught atmosphere, the lines between spiritual salvation and temporal power blurred. The pope wielded spiritual sanctions like excommunication as weapons that could topple monarchs. Conversely, emperors wielded armies and treasuries to protect or challenge the Church’s influence. The stakes were nothing short of the future architecture of European authority.

3. Emperor Henry IV: The Man Who Challenged God

Henry IV inherited a vast and fractious empire at the tender age of six. His early years as emperor were marked by regency struggles, noble revolts, and the ever-present shadow of papal ambitions. Known for a fierce, sometimes ruthless personality, Henry was a monarch who believed deeply in the divine right of kings—a belief that he alone had the God-given authority to govern and appoint his officials without papal interference.

When Gregory VII ascended to the papacy with a reformist zeal, Henry initially resisted. His kingdom was vast, stretching across modern-day Germany, Italy, and beyond, yet internally fragile and divided. Henry’s defiance of the pope’s reforms ignited a crisis that erupted into open conflict, which only escalated when Gregory excommunicated the emperor—a move that threatened to undermine Henry’s legitimacy and power entirely.

This excommunication was not merely spiritual condemnation; it was a political earthquake. It signaled to Henry’s many rebellious nobles and vassals that the emperor was no longer protected by divine authority—an invitation to rebellion.

4. Pope Gregory VII and the Reforming Zeal of the Gregorian Revolution

Born Hildebrand of Sovana, Gregory VII was a monk of the Cluniac reform movement before becoming pope in 1073. His vision was radical: to restore the Church's moral authority by eradicating corruption such as simony (the buying and selling of church offices) and enforcing celibacy among clergy. But perhaps his most revolutionary stance was the assertion that the pope, not kings or emperors, had the divine right to invest bishops with their symbols of office.

Gregory’s Dictatus Papae, a series of papal assertions, proclaimed the pope’s supremacy over all secular rulers—a doctrine that transformed the papacy from religious leader to political power broker with claim to supremacy. This set the stage for an inevitable and irreconcilable clash with Henry IV.

Gregory’s refusal to back down, even when faced with imperial defiance, turned the Investiture Controversy into a dramatic battle that rippled beyond Rome and Aachen into every corner of medieval Christendom.

5. The Investiture Controversy: Power Struggles Beyond Thrones

The heart of the conflict wasn’t simply between two men, but two competing ideologies of medieval kingship and governance. How and by whom should power be vested in bishops—a spiritual office with temporal power? For the emperor, controlling appointments ensured loyalty and political stability. For the pope, it was a matter of spiritual purity and autonomy.

The issue was complicated by regional politics. Many nobles favored the papal stance if it meant breaking the emperor’s grip, while others sided with the emperor to maintain order. Different rulers in Europe observed the conflict from afar, anticipating the outcome would shift the continental balance of power.

The controversy was as much about symbolism as substance—crowns, rings, and scepters embodied tangible authority. Each side wielded their spiritual or temporal tools with precision and calculation.

6. The Road to Canossa: From Excommunication to Desperation

By 1076, after years of escalating conflict, Gregory VII excommunicated Henry IV. The pope’s declaration was explicit: Henry was cut off from the Church and relieved of his right to rule—an open invitation to rebellion among his vassals and bishops.

This declaration emboldened the German princes, many of whom convened to depose the emperor and elect a rival king. Facing political isolation and rebellion, Henry’s position collapsed like a house of cards.

In a desperate bid to reclaim legitimacy and quash revolt, Henry decided to make a humbling pilgrimage to Canossa, where Pope Gregory was staying, seeking absolution and restoration in the dead of winter. This journey was perilous and symbolic—a public act of penance that intertwined political necessity and religious submission.

7. January 1077: The Icy Walk of Henry IV

As the snow fell thick and cold across the Apennines, Henry donned coarse sackcloth, discarded his royal robes, and set out on foot toward Canossa. The image is stark and unforgettable—the emperor, barefoot and vulnerable, braving icy winds and treacherous passes.

The journey was an act of immense personal humility and political theater. It was intended to demonstrate sincere repentance, to disarm the pope's spiritual weapon of excommunication, and to buy time against rebellious nobles.

The march itself inspired awe and rumor. Chroniclers would paint Henry’s desperation in vivid terms, some portraying him as broken, others as calculating—capable of both penance and political cunning.

8. The Three Days in the Snow: Waiting at the Castle of Canossa

Upon arrival, Henry found the gates of Canossa Castle barred. For three bitterly cold days, he stood in the snow outside the fortress walls, denied immediate admission—a penitent punished and humbled.

This episode has been preserved in medieval chronicles as a potent symbol of humility before God, and, by extension, before the spiritual authority of the pope. It became a powerful image illustrating the primacy of spiritual power over temporal might.

Yet, historians debate whether Gregory’s initial coldness was tactical or sincere, and whether Henry’s act was purely penitential or a strategic ploy.

9. The Moment of Reconciliation: Between Forgiveness and Politics

Eventually, Gregory relented. On January 28th, Henry was admitted, and the pope granted absolution—lifting the excommunication and restoring Henry’s status as emperor in the eyes of Christendom.

This moment was astonishing: the most powerful man in Europe humbled before the servant of God, fleeing divine wrath through a public act of submission.

The forgiveness was as much about politics as spirituality. Gregory needed a strong emperor to enforce his reforms, and Henry needed his blessing to maintain power.

Their reconciliation, however, was fragile; the war of wills was far from over.

10. The Symbolism of the Penance: Humility or Strategic Submission?

Was Henry IV’s penance at Canossa a deep religious transformation? Many chroniclers framed it as such, celebrating the triumph of spiritual authority. Yet, behind the silken cloaks of humility lay raw political calculations.

Henry’s submission bought him time—time to regroup, to deal with rebellious nobles, and to ultimately return in strength to fight the pope’s influence.

The event also established a potent symbol for centuries: the image of temporal rulers bowed before spiritual power, a potent motif resonant in European political theology.

11. Reactions in Europe: Chronicles, Rumors, and Propaganda

Word of Henry’s penance spread like wildfire across Europe. Chroniclers on all sides weighed in, many emphasizing different narratives: the pope’s moral victory, the emperor’s humiliation, or a stage-managed political drama.

In the Holy Roman Empire, many nobles saw the event as a moment of weakness, soon to be exploited. In Rome and other papal territories, the reconciliation was hailed as divine justice.

This event fed into the rivalries and propaganda battles, influencing the reputations of both pope and emperor in ways that would define their legacies.

12. The Aftermath: Did the Pope Really Triumph?

Despite the drama at Canossa, the bigger battle was only temporarily paused. Henry soon returned, raising armies and reclaiming power, while Gregory struggled to maintain papal authority amid rising opposition.

Henry’s excommunication was renewed later, and fighting resumed. The power balance remained delicate and fluid.

In many ways, Canossa was a symbolic moment—a powerful image that didn’t resolve the underlying conflicts but shaped their narrative for generations.

13. The Long Shadow of Canossa on Medieval Power Dynamics

Canossa became a watershed, marking the gradual assertion of papal political influence over secular rulers.

It emboldened the Church’s claims to spiritual supremacy, encouraging reform movements, and changing how kings justified their rule.

It influenced later conflicts and treaties, establishing a precedent that rulers needed papal sanction and that spiritual and temporal powers were deeply intertwined, if often in tension.

14. The Mythologizing of Canossa in Later Centuries

The phrase "going to Canossa" entered European political lexicon as a synonym for humiliating submission.

Enlightenment thinkers, nationalists, and politicians all invoked Canossa to critique or celebrate authority and obedience.

In 19th-century Germany, especially, it became a rallying point for debates about church and state, secularism, and nationalism, far beyond its medieval origins.

15. Canossa and the Making of Modern Church-State Relations

Beyond its medieval context, Canossa laid groundwork for evolving notions of sovereignty and authority.

It forced thinkers to confront the relationship between faith and politics, shaping doctrines that would influence the West’s political development.

This event foreshadowed later constitutional and secular arrangements where spiritual and earthly powers had to coexist with negotiated boundaries.

16. Personal Reflections: Henry IV and Gregory VII Beyond History

Behind the grand narrative were two complex men: Henry, a stubborn, passionate ruler, forged in youth turmoil, and Gregory, a principled, relentless reformer who bore the weight of papal office with visionary zeal.

Their confrontation was a collision of personalities as much as ideologies, full of ambition, fear, faith, and human frailty.

Their legacies remain entwined—two titans whose struggle shaped the medieval world.

17. The Architectural Legacy of Canossa Castle

Canossa Castle itself, perched on rugged hills, was not merely a backdrop but a symbol of power and refuge.

Its walls witnessed this extraordinary moment of penance, and its ruins have survived the centuries as silent testimony to one of history’s most dramatic power plays.

18. Parallels in History: When Pride Meets Penitence

History is replete with rulers humbled by spiritual or political forces: Napoleon’s exile, Louis XVI’s trial, or Mandela’s reconciliation.

Canossa remains a profound example of the vulnerability of power and the potency of symbolic acts of submission.

19. The Role of Memory and Historical Narrative in Shaping Canossa

How Canossa is remembered reveals as much about the societies retelling it as about the event itself.

The competing narratives—of humiliation, triumph, piety, and strategy—show the power of history to serve political and cultural agendas.

20. Conclusion: A Moment Frozen in Ice and Time

The penance of Henry IV at Canossa was much more than a footnote in medieval chronicles. It was a moment where power, faith, and humanity collided in icy stillness. It showed that even emperors, crowned and mighty, bear the fragile weight of spiritual judgment and political survival.

Canossa is a mirror reflecting the complexities of authority and humility, politics and belief, history shaped by human ambition and divine mystery. It reminds us that history is never just about grand events, but the fragile, dramatic moments where personal choice and destiny entwine.

FAQs

Q1: Why did Henry IV undertake such a humiliating journey to Canossa?

A1: Henry’s journey was driven by political desperation to have his excommunication lifted and regain legitimacy among his rebellious nobles. Though it was framed as penance, it was a calculated move to restore power.

Q2: What was the Investiture Controversy about?

A2: The controversy centered on who had the authority to appoint bishops and invest them with spiritual symbols—emperors feared losing control over vital political allies if the Church assumed that power.

Q3: How did Pope Gregory VII view the conflict?

A3: Gregory saw it as a divine mission to reform the Church and assert papal authority over secular rulers, asserting that the pope’s spiritual power trumped all earthly sovereignty.

Q4: Did the penance at Canossa end the conflict?

A4: No. Although Henry was absolved, the broader investiture conflict continued for decades, with ongoing struggles between emperors and popes reshaping medieval Europe.

Q5: How has Canossa been interpreted in later history?

A5: Canossa became a symbol of submission and power struggles, referenced in political discourse for centuries as an example of rulers humbled by higher authority.

Q6: What does Canossa tell us about medieval society?

A6: It reveals a world where spiritual and temporal powers clashed yet were deeply intertwined, where symbols and rituals could wield immense political force.

Q7: Was Henry IV’s act sincere penance or political maneuvering?

A7: Historians debate this, with many agreeing it was a complex mixture—an act of real humility intertwined with strategic calculation.

Q8: What is the legacy of Canossa today?

A8: Canossa remains a powerful metaphor for the limits of power and the enduring tension between secular and religious authority, relevant in understanding history and politics even now.