Table of Contents

- The Tense Prelude: Europe on the Brink of a Spiritual Crisis

- The Investiture Controversy: Power, Faith, and Ambition Entwined

- The Emperor vs. The Pope: A Clash of Titans

- The Road to Worms: Decades of Conflict and Negotiation

- The Holy Roman Empire: A Fragmented Political Landscape

- Pope Callixtus II: The Man Behind the Papal Banner

- Emperor Henry V: The Last Stub of Imperial Defiance

- The Arrival at Worms: Setting the Stage for Resolution

- September 23, 1122: The Signing of the Concordat

- The Terms of the Concordat: A Delicate Compromise

- Immediate Reactions: Relief, Suspicion, and Celebration

- The End of the First Phase: What Was Truly Settled?

- Consequences for Church Authority: The Pope’s Strengthened Grip

- Imperial Power Recalibrated: Limitations and Legitimacy

- The Broader European Impact: A Template for Church-State Relations

- Beyond Worms: The Continued Struggle for Investiture

- Lessons in Diplomacy: The Art of Compromise in Medieval Politics

- The Concordat’s Legacy in Modern Church-State Relations

- Human Stories: The Clerics and Laypersons Behind the Politics

- Anecdotes and Insights: Voices from the Past

- The Concordat in Historical Memory and Scholarship

- Conclusion: A New Chapter in Medieval Christendom

- FAQs: Understanding the Concordat of Worms

- External Resource: Wikipedia Link

- Internal Link: More Historical Narratives at History Sphere

Europe stood divided in faith and power as the autumn sun set over the imperial city of Worms in 1122. The air was thick with anticipation and weary from decades of bitter strife. Nobles, bishops, knights, and commoners alike watched, some with hopeful eyes, others with wary hearts. Across the sprawling Holy Roman Empire and far beyond, the world waited for the ink to dry on a document that promised to end one of the most protracted and profound conflicts of medieval Christendom: the Investiture Controversy.

At the heart of this saga lay a fundamental question about authority—who had the right to appoint bishops and abbots, the powerful territorial lords of the Middle Ages: the Emperor, representing secular might, or the Pope, guardian of spiritual purity? For nearly half a century, this struggle had torn at the fabric of European society, pitting the papacy against the imperial throne in a contest with consequences far beyond the disputed ceremonies.

The Concordat of Worms, signed on that crisp September day, was more than a mere treaty. It was a turning point—a fragile peace woven from the threads of diplomacy, mutual exhaustion, and the recognition that neither side could afford total victory. This agreement laid the groundwork for the modern balance between church and state and signaled the end of the first phase of a conflict that had at times threatened to rend Western Christendom asunder.

But to understand the Concordat fully, one must journey back through the tangled political landscapes of 11th and early 12th century Europe, where faith was power, authority was contested at every turn, and the stakes were nothing less than the soul of the Christian world.

The Investiture Controversy was born from increasing tensions between two poles of medieval society: the spiritual authority exercised by the Church and the temporal power held by kings and emperors. The conflict centered on the ceremony of investiture—who could formally install bishops and abbots into their office, a ritual that conferred not just spiritual authority but extensive political and economic influence.

By the mid-11th century, reformist popes, energized by movements to free the Church from secular interference and moral corruption, began to insist that only the Church had the right to appoint its officials. This challenge directly confronted the traditional claims of kings and emperors who had long used ecclesiastical appointments as tools to bolster their own power, rewarding loyal nobles and managing vast territories governed by the clergy.

The Investiture Controversy erupted most fiercely in the Holy Roman Empire, a sprawling and fractured realm where the Emperor’s authority was by no means absolute. Here, the conflict took a personal and bitter turn between Emperor Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII, culminating in dramatic episodes like the emperor’s penitent journey to Canossa in 1077.

Yet the conflict did not end there; subsequent emperors and popes continued the power struggle well into the next century. This tug-of-war over supremacy not only embroiled religious leaders but also touched all levels of medieval society, from local nobles to peasantry, fracturing loyalties and destabilizing political structures.

The political map of Europe during this era was complicated. The Holy Roman Empire stretched across Germany, northern Italy, and parts of what are now France, the Low Countries, and Eastern Europe. Power was decentralized; dukes, counts, bishops, and princes jostled for autonomy and influence under a generally weak imperial crown. The Church was a vast institution with immense landholdings, spiritual clout, and a burgeoning bureaucracy dedicated to governance and reform—the papacy emerged as a centralizing force with a vision for a universal church ruled from Rome alone.

Enter Pope Callixtus II, a seasoned churchman dedicated to restoring order after decades of turmoil. On the opposing side stood Emperor Henry V, son of Henry IV, who had inherited a fractious empire and a poisoned relationship with the papacy. Both men were pragmatists, war-weary and perhaps weary of a conflict that had brought more ruin than glory.

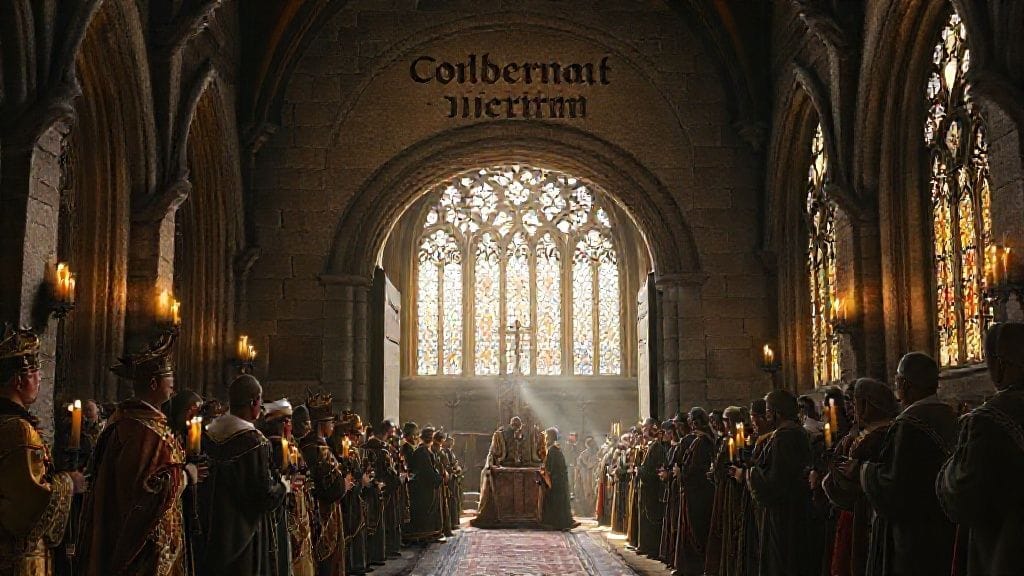

In the summer of 1122, the emperor and the pope arranged to meet at Worms, a fortified city with a dual identity—both an imperial seat and a spiritual center. Delegations arrived from across the empire, bringing with them the hopes and fears of a continent eager for renewal.

The negotiations were tense, intricate, and protracted. Both sides had to square deeply entrenched principles with political realities, each cautious of yielding too much lest they lose ground forever. The final document, the Concordat of Worms, was a masterstroke of compromise. It distinguished between the spiritual and secular aspects of investiture: the Church would invest bishops with their spiritual authority, the ring and staff symbolizing their sacred office, while the emperor retained the right to invest them with secular titles and temporal powers with a sceptre—the symbol of worldly lordship.

This division of powers acknowledged the separate spheres of church and state without fully subordinating one to the other. It was a concession born of exhaustion and mutual recognition, but also a milestone in the long development of Western political thought.

Immediate reactions were mixed. Many in the Church hailed it as a victory for papal reform and autonomy, while imperial loyalists cautioned that the emperor’s role in selecting bishops, albeit limited, remained intact. Yet, universally, the Concordat brought relief—it ended decades of open hostility and cleared the way for further negotiation on other thorny medieval issues.

But the Concordat was not the final word. The struggle over investiture would quietly persist in different forms for years, revealing the complexities of power relations and highlighting the perennial tension between spiritual ideals and political realities.

The papacy emerged strengthened, its reforms emboldened, setting the tone for the rise of a more centralized and assertive church throughout the High Middle Ages. The emperor’s authority was formally curtailed but preserved, foreshadowing the gradual evolution of the Holy Roman Empire into a patchwork of semi-independent states rather than a unified absolutist kingdom.

Across Europe, the Concordat became a precedent, a reference point for church rulers and secular monarchs negotiating their own delicate balances. It signaled a shift towards institutional differentiation—a crucial step in the long formation of distinct political and religious legal systems that still define much of Europe today.

Beyond the immediate political and administrative outcomes lay human stories of lost friends, betrayed loyalties, and the faith of countless ordinary people caught up in events far beyond their control. Chroniclers of the age preserved these moments—vivid accounts of negotiations, disputes, and the lives transformed by the convergence of the sacred and the profane.

Medieval chronicler Otto of Freising recounted with a striking mixture of hope and realism: “This agreement was not merely the settling of a quarrel but a new covenant, promising that earthly rulers would no longer cast shadows over the sacred duties of shepherds of souls.”

Today, historians reflect on the Concordat of Worms as a seminal moment in Western civilization’s path to reconciling competing claims of faith and governance. Beyond its immediate historical context, it offers timeless lessons in compromise and the art of diplomacy—reminded that in even the most intractable conflicts, dialogue and negotiation can open doors to peace.

Conclusion

The Concordat of Worms was more than a legal instrument; it was a moment of transformation in medieval Europe’s turbulent tapestry. It marked the end of a bitter chapter in church and imperial relations—a chapter scarred with excommunications, wars, and political machinations—but it also inaugurated a critical dialogue about the nature of authority that resonates to this day. The agreement was born of turmoil but crafted with mutual respect and pragmatism, a testament to the enduring human capacity to seek common ground.

By delineating the spiritual from the temporal, the Concordat laid down lines that would shape Western politics and religion for centuries. It was neither a total victory nor defeat for either pope or emperor but a profound acknowledgment that power must, at times, bow to principle. More than 900 years later, the echoes of Worms remind us that questions of authority, legitimacy, and belief remain central to human societies—and that even when faith and power clash, there is hope for concord.

FAQs

Q1: What was the Investiture Controversy about?

A1: The Investiture Controversy was a conflict over who had the right to appoint local church officials—bishops and abbots—who held not only spiritual authority but also temporal power. It pitted the Holy Roman Emperors against the Popes from the mid-11th to early 12th century.

Q2: Why was the Concordat of Worms signed in 1122 significant?

A2: It ended the first phase of the Investiture Controversy by establishing a compromise: the Church would invest bishops with spiritual authority, while emperors retained the right to confer secular powers, thereby balancing spiritual independence with imperial jurisdiction.

Q3: Who were the main figures involved in the Concordat?

A3: Pope Callixtus II and Emperor Henry V were the key signatories, both pragmatic leaders weary of continuous conflict who negotiated the compromise.

Q4: Did the Concordat of Worms end all conflicts between the church and empire?

A4: No. While it ended the first and most violent phase of the Investiture Controversy, power struggles between popes and emperors continued intermittently over subsequent centuries.

Q5: How did the Concordat affect the balance of power in medieval Europe?

A5: It strengthened papal authority over spiritual appointments but preserved imperial influence in secular matters, fostering a clearer separation between church and state that influenced European political development.

Q6: What lessons does the Concordat of Worms offer today?

A6: It demonstrates the importance of dialogue, compromise, and respecting distinct spheres of influence in resolving seemingly irreconcilable conflicts.

Q7: How is the Concordat remembered in historical scholarship?

A7: It is widely regarded as a turning point in medieval history and an early foundation of the modern concept of church-state relations.

Q8: Why Worms? Was the city significant?

A8: Worms was a key imperial city and ecclesiastical center, symbolically appropriate as a meeting point between secular and spiritual powers.