Table of Contents

- The Lingering Chill of a December Night: Death of John Wycliffe

- England in the Late 14th Century: A Nation on the Brink

- John Wycliffe: From Oxford Scholar to Spiritual Revolutionary

- The Seeds of Dissent: Wycliffe’s Early Challenges to Church Authority

- The Translation of the Bible: A Radical Act of Faith and Defiance

- The Clash with the Church: Ecclesiastical Condemnations and Political Intrigue

- The Lollards: Wycliffe’s Legacy Takes Root in English Soil

- December 31, 1384: The Final Moments in Lutterworth

- The Silent Funeral: Wycliffe’s Burial and the Church’s Uneasy Conscience

- Posthumous Trials and the Church’s Hunt for Heresy

- The Burning of Wycliffe’s Bones: A Spectacle of Power and Fear

- Wycliffe’s Doctrine and Its Enduring Echo in English Reformation

- The Political and Social Tremors Following Wycliffe’s Death

- Lutterworth Today: Pilgrimage Site and Historical Memory

- The Global Legacy of John Wycliffe: From England to the World

- Conclusion: A Voice That Refused to be Silenced

- FAQs: Exploring the Life, Death, and Legacy of John Wycliffe

- External Resource

- Internal Link

The winter wind cut sharply through the narrow lanes of Lutterworth as the year 1384 drew to a close. On the final day of that icy December, a man whose ideas had lit fires far more potent than the hearths of England’s homes breathed his last. John Wycliffe, the Oxford scholar turned radical theologian, died quietly in a modest rectory, his life marked by controversy, conviction, and an unyielding quest for spiritual truth. But this was no ordinary passing; it was the end of a chapter fraught with tremors echoing through centuries, forever altering the course of religious thought.

England in the Late 14th Century: A Nation on the Brink

To grasp the magnitude of Wycliffe’s death, we must first peer into the England he lived in—a realm simmering with unrest, corruption, and a thirst for change. The mid-to-late 1300s were shadowed by the aftershocks of the Black Death, which had decimated the population and strained societal structures. The Hundred Years’ War with France drained resources and morale, while the Chandos rebellion and the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 laid bare the widening chasm between the classes.

At the spiritual helm stood the Roman Catholic Church, an institution wielding immense power but increasingly criticized for clerical greed, moral decay, and political interference. The distinction between church and state blurred, and with Rome’s distant dominance over English affairs, the land was ripe for voices challenging this hegemony. Among these voices, few would resonate as profoundly as John Wycliffe’s.

John Wycliffe: From Oxford Scholar to Spiritual Revolutionary

Born around 1320, Wycliffe’s journey began modestly but with remarkable intellectual vigor. Educated at Oxford University, he excelled in theology and philosophy, eventually becoming a fellow of Merton College. His erudition propelled him into influential positions within academia and church circles, yet his mind was restless, probing the inconsistencies of ecclesiastical practices and dogma.

Wycliffe’s critical stance emerged from a profound conviction: the Scriptures alone constituted the ultimate authority on spiritual matters. This belief propelled him toward challenging clerical corruption, the accumulation of wealth by church officials, and the papal claims over temporal power. His writings, forged in the fires of scholastic rigor and spiritual fervor, branded him as a formidable opponent of the entrenched Church hierarchy.

The Seeds of Dissent: Wycliffe’s Early Challenges to Church Authority

Wycliffe’s early treatises laid bare the contradictions he saw within Christendom. His careful yet scathing critiques argued that many practices were not found in the Bible and should therefore be discarded. For instance, he condemned the doctrine of transubstantiation—the belief that bread and wine literally become the body and blood of Christ during the Eucharist—as unscriptural and misleading.

These positions shocked many contemporaries and made Wycliffe an object of suspicion and hostility. Yet, his position as a canon of Lutterworth provided him shelter and a platform. From this rural parish, Wycliffe’s voice traveled far beyond England’s borders, inspiring theologians and laypeople alike. He called for the Church to return to apostolic simplicity and poverty—demands radical for his time.

The Translation of the Bible: A Radical Act of Faith and Defiance

Perhaps Wycliffe’s most revolutionary contribution was his push to translate the Bible into vernacular English. Until then, Scripture remained largely inaccessible to ordinary people, locked away in Latin, the language of the clergy. To Wycliffe, this gap strangled true faith.

Between the 1380s and his death, Wycliffe undertook or inspired translations of the Bible that became the first known English versions—later dubbed the “Wycliffe Bible.” This was no simple academic exercise: it was a calculated act of democratization, meant to empower the laity to engage directly with the Word of God.

The Church viewed this with alarm. The monopoly on scriptural interpretation was a pillar of clerical authority. Wycliffe’s endeavors foreshadowed the Reformation by nearly two centuries, hinting at the shift that would one day sweep across Europe.

The Clash with the Church: Ecclesiastical Condemnations and Political Intrigue

Resistance to Wycliffe’s ideas swiftly escalated. He was summoned multiple times to defend himself before ecclesiastical tribunals; in 1377, Pope Gregory XI condemned several of his propositions as heretical. Yet, Wycliffe found protection in John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, one of the most powerful nobles in England, illustrating the intricate dance between political and religious power.

Despite condemnation, Wycliffe’s ideas spread among English nobility, university circles, and commoners alike. His defiance of papal authority coincided with nationalist sentiments seeking to wrest England’s church from foreign control.

The Lollards: Wycliffe’s Legacy Takes Root in English Soil

The followers of Wycliffe, derisively called “Lollards,” became a grassroots movement advocating his reforms—Scripture in English, clerical poverty, and a direct relationship with God. Lollardy spread through sermons, secret gatherings, and clandestine Bible readings.

Their growing influence unsettled the Church and the monarchy, which increasingly perceived them as a threat to religious unity and political order. The movement would endure long after Wycliffe’s death, sowing the seeds for later church reformations.

December 31, 1384: The Final Moments in Lutterworth

In the cold twilight of that winter’s eve, John Wycliffe passed away while serving as rector in the modest parish church of Lutterworth. Accounts suggest he died peacefully, immersed in prayer or reflection, far from the hostile tribunals and fires that awaited his memory.

Imagining that moment is to picture a man who had dared to challenge the world’s mightiest institution, now silenced but not subdued. His death marked the end of a lifetime of fierce intellectual battles and spiritual struggles but was only the beginning of his ideas’ tumultuous journey.

The Silent Funeral: Wycliffe’s Burial and the Church’s Uneasy Conscience

Wycliffe was buried in the churchyard of Lutterworth; however, his resting place was anything but tranquil for those who feared his legacy. While the villagers may have mourned their beloved rector, the Church’s hierarchy viewed his tomb with suspicion—a silent challenge to their doctrine.

For decades afterward, pilgrims and reformers would visit Lutterworth, seeking inspiration from the man who had dared to question the spiritual oligarchy.

Posthumous Trials and the Church’s Hunt for Heresy

In a striking postmortem rebellion, the Church tried and condemned Wycliffe’s teachings nearly two decades after his death. In 1415, the Council of Constance officially declared Wycliffe a heretic, and in an act of symbolic vengeance, his remains were exhumed and burned.

This macabre spectacle was intended to erase Wycliffe’s influence, but it ironically immortalized it further. Such a dramatic condemnation revealed the deep anxiety the Church felt toward ideas that threatened its control.

The Burning of Wycliffe’s Bones: A Spectacle of Power and Fear

The public burning of Wycliffe’s bones at the Council of Constance was not merely an act of religious purification; it was a performative assertion of authority. The ashes were scattered in the River Swift—a deliberate message that Wycliffe’s “heretical” teachings must be swept away.

Far from achieving oblivion, this gruesome ritual transformed Wycliffe into a martyr for intellectual freedom and religious reform, echoing in the hearts of future reformers.

Wycliffe’s Doctrine and Its Enduring Echo in English Reformation

Wycliffe’s calls for scriptural authority, vernacular access, and church reform resonated in the coming centuries. The Lollards’ persistence and the English Reformation of the 16th century, led by figures like Thomas Cranmer and William Tyndale, bore the imprint of Wycliffe’s pioneering courage.

His insistence on the Scriptures as the supreme authority laid the theological groundwork that would fracture medieval Christianity and birth Protestantism.

The Political and Social Tremors Following Wycliffe’s Death

Beyond theology, Wycliffe’s ideas intersected with the sociopolitical fabric of England. His critique of ecclesiastical wealth and foreign papal influence aligned with emerging nationalist and anti-clerical sentiments. This helped kindle debates about governance, society, and rightful authority, shaping the future of English statehood.

Moreover, the empowerment of laypeople to read and interpret Scripture challenged hierarchies far beyond the church—nudging society towards individual conscience and spiritual autonomy.

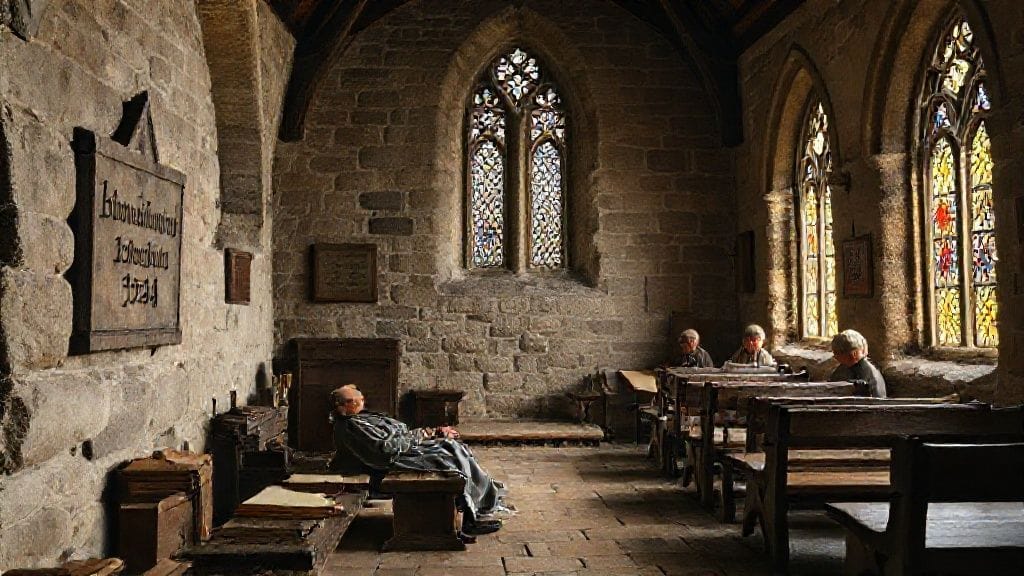

Lutterworth Today: Pilgrimage Site and Historical Memory

Centuries later, Lutterworth remains a place of pilgrimage for historians, theologians, and seekers of spiritual heritage. The church of St. Mary, where Wycliffe served and died, preserves his memory with plaques and exhibitions.

Visitors walk the same stone floors, contemplating the life of a man who lived on the razor’s edge of controversy, transforming England’s religious landscape forever.

The Global Legacy of John Wycliffe: From England to the World

Though rooted in the soil of medieval England, Wycliffe’s impact is global. Being dubbed the “Morning Star of the Reformation” is no exaggeration—his principles of scriptural primacy and vernacular access inspired reformers from Martin Luther to William Tyndale, whose English translations formed the basis of modern Bibles.

Wycliffe showed the power of ideas to traverse centuries and continents, igniting movements for faith, freedom, and knowledge.

Conclusion

John Wycliffe’s death on that cold December day in 1384 was far more than the quiet end of a provincial cleric’s life. It was a pivotal moment suspended between medieval orthodoxy and the coming dawn of reform. His life intertwined courage with intellect, his death marked by peace yet shadowed by controversy.

Wycliffe’s story is a testament to the enduring human longing for truth, access, and justice—even when such quests invite isolation and persecution. Standing at the crossroads of history, he exemplifies how one man’s voice, once whispered in a small English parish, can echo timelessly through the ages, challenging institutions and inspiring generations.

FAQs

Q1: What were the main criticisms John Wycliffe had against the Catholic Church?

A1: Wycliffe criticized the Church’s accumulation of wealth, moral corruption, the doctrine of transubstantiation, and papal authority over secular rulers. He believed the Scripture alone should guide Christian life, rejecting practices not supported by the Bible.

Q2: Why was translating the Bible into English so controversial in Wycliffe’s time?

A2: The Church maintained exclusive control over Scripture interpretation, which was central to its power. Translating the Bible into English made religious texts accessible to common people, threatening clerical authority and risking divergent interpretations deemed heretical.

Q3: Who protected Wycliffe from early persecution?

A3: John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster and a powerful noble, offered political protection to Wycliffe, shielding him from harsher Church sanctions during his lifetime.

Q4: What happened to Wycliffe’s followers after his death?

A4: Known as Lollards, Wycliffe’s followers continued to spread his ideas, often in secret, facing persecution but significantly influencing later reform movements in England.

Q5: How did the Church respond to Wycliffe’s death and legacy?

A5: The Church condemned his teachings posthumously, tried him for heresy, and exhumed and burned his bones in 1415 to symbolically eradicate his influence.

Q6: In what ways did Wycliffe influence the English Reformation?

A6: Wycliffe laid theological and ideological foundations by advocating Scripture’s supremacy and vernacular translation, directly inspiring reformers such as William Tyndale and indirectly shaping Protestant thought.

Q7: Why is Wycliffe sometimes called the "Morning Star of the Reformation"?

A7: Because his ideas anticipated and paved the way for the Protestant Reformation centuries later, marking the early light that foreshadowed profound religious upheaval.

Q8: What is the significance of Lutterworth today in relation to Wycliffe?

A8: Lutterworth is a historic site preserving Wycliffe’s memory, attracting scholars and visitors who wish to connect with his legacy and the birthplace of English religious reform.