Table of Contents

- A Final Winter’s Day: The Death of George Washington

- The Setting: Mount Vernon at the End of an Era

- The Man Behind the Legend: George Washington’s Journey to 1799

- Early Signs: The Sudden Illness Begins

- Medical Practices in the 18th Century: A Battle Against Time

- The Final Hours at Mount Vernon

- Family and Friends: Bearing Witness to History

- The Official Announcement: A Nation in Mourning

- Mourning a Nation’s Father: Public Reaction and Memorials

- The Funeral Procession at Mount Vernon

- Washington’s Legacy in the Heart of the New Republic

- The Tomb and the Estate: Preserving a Hero’s Memory

- Reflections of Contemporaries: Letters and Eulogies

- Myths, Facts, and Speculations: The Mysteries Surrounding His Death

- How Washington’s Death Shaped the Young United States

- The Evolution of Washington’s Image Post-1799

- Mount Vernon as a Pilgrimage Site: From Private Home to National Shrine

- George Washington in American Collective Memory

- Medical Retrospections: What Killed George Washington?

- The Last Will and Testament: A Man Planning Beyond Death

- Lessons from a Leader’s Passing

- Conclusion: The End of the First American Chapter

A Final Winter’s Day: The Death of George Washington

It was a cold December day in 1799, a biting chill sweeping through the woods and fields around Mount Vernon. The sky was a dull gray, heavy with the weight of winter’s advance. Inside the stately mansion, the hearth’s fire flickered weakly, casting long shadows on the walls as a hush fell over the household. George Washington, the towering figure whose presence had shaped the destiny of a nation, lay gravely ill, his once indomitable spirit dimming before the dawn of a new century.

As the day wore on, a solemn stillness settled. Outside, the wind whispered through the trees, carrying the news like a silent herald: the first president of the United States was dying. The stoic leader, the revered general, the emblem of American endurance, was slipping away. Moments later, on December 14th, 1799, George Washington breathed his last. The birth of a nation had lost its father, but his legacy was only just beginning to unfurl.

The Setting: Mount Vernon at the End of an Era

Mount Vernon stood as a sentinel overlooking the Potomac River, a sprawling estate that mirrored the man who had shaped it—steadfast, proud, and steeped in history. Washington had returned here in 1797 after serving two terms as the nation’s first president, retreating to the quiet dignity of plantation life with the hope of enjoying peace in his final years.

But tranquility was fragile that winter. The estate, typically alive with the bustle of agricultural life, seemed subdued under the pall of Washington’s worsening illness. Servants and family members moved silently along the corridors, their faces etched with concern. In many ways, the fate of Mount Vernon felt inseparable from that of its master.

The Man Behind the Legend: George Washington’s Journey to 1799

George Washington’s life had often seemed larger than life. Born into Virginia’s plantation aristocracy in 1732, he rose from a surveyor and militia officer to become the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. His leadership during the American Revolution forged the fledgling United States’ path to independence and defined its character.

After two presidential terms marked by precedent-setting and delicate political balancing, Washington retired to Mount Vernon, his health already waning after years of strenuous public service. By the late 1790s, his standing was not only as a leader but as a symbol of unity and resilience in a still-fragile republic.

Early Signs: The Sudden Illness Begins

On December 12th, 1799, Washington was out inspecting his estate in the raw cold of the Virginia winter. As legend tells, a sudden storm drenched him as he hurried back to the mansion, his cold rising rapidly into a severe sore throat. In just 24 hours, his condition deteriorated dramatically.

What began as a mild cold escalated into a grave respiratory illness. Washington developed a harsh, painful throat and difficulty breathing—early signs of what physicians of the time would struggle to treat. Despite his robust constitution, age and exhaustion weighed upon him.

Medical Practices in the 18th Century: A Battle Against Time

Medicine in 1799 was steeped more in tradition and limited understanding than in science. Treatments included bloodletting, purging, and the administration of various concoctions. Skilled though they were for their time, physicians had few means to combat the acute respiratory distress that Washington endured.

Three doctors attended to him, attempting to draw blood in the hope of balancing his humors—a common practice but one that modern historians speculate may have hastened his decline. The medical urgency at Mount Vernon was desperate, with practitioners acting swiftly but ultimately impotent to change the course of his illness.

The Final Hours at Mount Vernon

As December 14th dawned, Washington’s condition worsened rapidly. His breathing was shallow, his voice nearly gone. He summoned his wife Martha and close attendants, expressing gratitude and concern for his family’s future.

Without fanfare, in the early evening of that day, George Washington quietly passed away, reportedly uttering only his final statement: "It is well, I die hard, but I am not afraid to go."

His death was the closing of an epoch, a moment wrapped in solemnity and profound national sorrow.

Family and Friends: Bearing Witness to History

Martha Washington’s grief was overwhelming, yet she remained composed, embodying the stoicism expected of a leader’s spouse. Close friends and surviving relatives gathered at Mount Vernon, their faces reflecting a mix of sorrow, respect, and disbelief.

Among the witnesses was Bushrod Washington, George’s nephew and heir, who would oversee the estate’s future and the preservation of his uncle’s legacy. Letters sent to and from Mount Vernon during this period reveal a personal and intimate portrait of mourning, brimming with admiration for the deceased patriarch.

The Official Announcement: A Nation in Mourning

News of Washington’s death spread with a speed remarkable for the late 18th century. The fledgling government and citizens alike were cast into widespread mourning. Official proclamations honored the memory of the man who had been the “Father of His Country,” while towns and cities held days of remembrance.

Congress adjourned, flags flew at half-mast, and public buildings rang bells in commemoration. Washington’s death was not merely the loss of a man but the symbolic passing of an era.

Mourning a Nation’s Father: Public Reaction and Memorials

Across the new United States, grief took visible, torch-bearing forms. In Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and beyond, processions moved solemnly, and poetry and oratory poured forth. Newspapers printed eulogies celebrating his virtues—his courage, humility, and unwavering dedication to republican ideals.

Church services dedicated to his memory became ritual acts of national unity, while emerging political voices sought to frame his legacy in ways that would inspire future generations.

The Funeral Procession at Mount Vernon

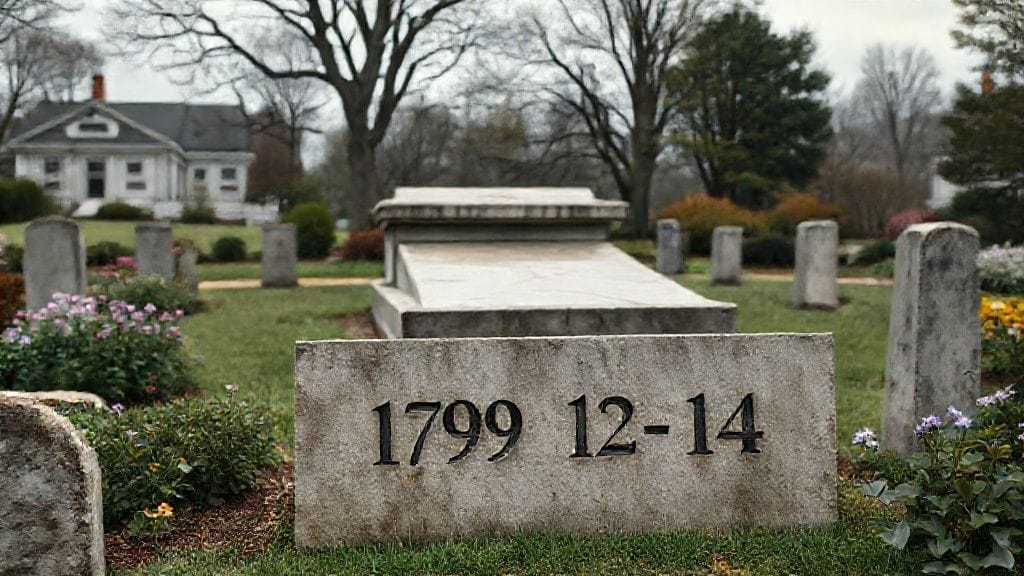

On December 18th, 1799, George Washington was laid to rest in a family tomb constructed decades earlier on the Mount Vernon grounds. The funeral procession was a gathering of dignitaries, soldiers, family, and townsfolk—a final tribute to the man who had led them to freedom.

The ceremony was marked by simplicity and solemnity, reflecting Washington’s own aversion to grandeur. Yet, the weight of history lent the moment a profound majesty; the first great American hero was now silent, buried in the soil he had fought to protect.

Washington’s Legacy in the Heart of the New Republic

Even in death, George Washington’s influence loomed large. His leadership, his carefully cultivated image as a servant of the people, and his role in defining the republic’s character entrenched him as the guiding star of American political culture.

The nation, still young and fragile, leaned on his memory as a touchstone of unity and stability during times of turmoil and political division.

The Tomb and the Estate: Preserving a Hero’s Memory

Mount Vernon quickly became a sacred site. Martha Washington, until her death in 1802, guarded the estate and ensured his burial place remained undisturbed. Over the following decades, the estate passed through the Washington family, gradually becoming accessible to visitors drawn by reverence for the past.

In time, preservation efforts transformed Mount Vernon into a living museum, a tangible bridge between the country’s origins and its ever-evolving present.

Reflections of Contemporaries: Letters and Eulogies

The outpouring of reflection from Washington’s contemporaries offers a rich mosaic of human emotion and political insight. Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and many others wrote movingly about the man who had embodied their highest aspirations.

One notable tribute came from Lafayette, who extolled Washington as “the greatest man I have ever known,” capturing the international dimension of his renown.

Myths, Facts, and Speculations: The Mysteries Surrounding His Death

Washington’s death, like much of his life, became shrouded in stories and speculations. Was it acute epiglottitis, pneumonia, or a combination that conquered him? Did the treatments hasten his demise? Modern medical historians continue to debate these questions, piecing together letters, doctors’ notes, and contemporary accounts to uncover the truth.

These inquiries humanize Washington, revealing the limits not only of 18th-century medicine but of the legend itself.

How Washington’s Death Shaped the Young United States

Washington’s passing served as a sobering marker of the fragile mortality that even the greatest leaders share. It also catalyzed the consolidation of national identity, reminding Americans of the ideals worth protecting.

Politically, it underscored the importance of peaceful succession and constitutional governance—a principle Washington himself had championed by stepping down from office voluntarily.

The Evolution of Washington’s Image Post-1799

As decades passed, George Washington’s image evolved from that of a mere historical figure to a near-mythical icon. Portraits, statues, currency, and ritual ceremonies enshrined his symbolism as the ultimate patriot and founding father.

Politicians across party lines invoked him to legitimize their causes, making Washington’s legacy a living, sometimes contested, force in American cultural and political life.

Mount Vernon as a Pilgrimage Site: From Private Home to National Shrine

Mount Vernon gradually transformed from a family plantation into a site of pilgrimage. Visitors journeyed to stand where Washington had walked, to touch the walls that held his memory. Preservation societies formed, and Congress eventually designated the estate as a protected historic landmark.

This evolution reflects the enduring power of place in the preservation of collective memory.

George Washington in American Collective Memory

Washington’s death marked the beginning of an expansive national mythology that continues to define American identity. He became more than a man: a symbol of courage, integrity, and democratic aspiration.

From school textbooks to holiday celebrations, the reverence for Washington’s life and death weaves through the nation’s consciousness like a sacred thread.

Medical Retrospections: What Killed George Washington?

In the centuries after, forensic analyses and medical retrospectives have wrestled with understanding the exact cause of Washington’s death. Acute epiglottitis, an inflammation of the throat that blocks the airway, is the leading theory, complicated by the bloodletting performed by his doctors.

The tragedy lies not only in the illness but in the limits of contemporary science—a stark reminder of how even the greatest minds of the age were vulnerable to nature’s forces.

The Last Will and Testament: A Man Planning Beyond Death

George Washington’s will, crafted with meticulous care, revealed his humanity beyond politics. It addressed the future of his estate, his slaves, and his debts, showing a man wrestling with the moral and practical complexities of his time.

The will also reflected his hopes for his family’s legacy and for the nation—a testament that his influence endured beyond his lifespan.

Lessons from a Leader’s Passing

Washington’s death taught the young United States vital lessons about leadership, humility, and the passage of time. His willingness to relinquish power and his acceptance of mortality embodied the principles of republicanism and civic responsibility.

His life’s end continues to inspire reflection on how leaders prepare their societies for their eventual absence.

Conclusion

George Washington’s death in December 1799 was not merely the loss of an individual but the closing chapter of a formative epoch in American—and indeed world—history. His passing transformed grief into a potent symbol of unity, perseverance, and hope for a fledgling nation still searching for its identity.

Washington’s final moments, at Mount Vernon in the quiet cold of winter, encapsulate the deeply human dimensions of history: strength matched with vulnerability, a public icon softened by personal tenderness, and an enduring legacy that would shape a nation’s soul.

As we remember that final winter’s day, we are reminded that history is alive—not only in grand narratives but in the intimate moments of parting, memory, and the enduring power of example.

FAQs

Q1: What illness caused George Washington’s death?

Most historians agree that Washington likely died of acute epiglottitis or severe acute bacterial infection of the throat, exacerbated by bloodletting—a common but harmful treatment of the era.

Q2: How did Washington’s death impact the young United States politically?

His death symbolized the passing of the revolutionary generation and reinforced the importance of stable governance and peaceful power transitions in the republic.

Q3: Who attended Washington’s final hours at Mount Vernon?

His wife Martha Washington, close family members such as his nephew Bushrod Washington, and three attending doctors stood vigil during his last moments.

Q4: Were there any immediate public tributes to Washington after his death?

Yes, nationwide mourning ensued with official proclamations, church services, flag half-masting, and processions in major cities.

Q5: How did medical practices of the time influence Washington’s death?

Bloodletting, purging, and other treatments likely worsened his condition, reflecting limited medical knowledge of respiratory illnesses at the time.

Q6: What is the significance of Mount Vernon today?

Mount Vernon is preserved as a historic site and museum, serving as a pilgrimage destination and symbol of Washington’s enduring legacy.

Q7: Did Washington make provisions for his slaves in his will?

Washington’s will provided for the gradual emancipation of his slaves after the death of his wife Martha, reflecting his complex views on slavery.

Q8: Why is Washington’s death considered the end of an era?

His passing marked the end of the revolutionary generation and the beginning of a new phase in American political and cultural life.