Table of Contents

- The Waning Twilight of a Revolutionary: March 12, 1925

- Beijing in the Early 1920s: A City on the Edge

- Sun Yat-sen: The Man Who Shaped Modern China

- From Birth to Revolutionary: The Journey of Sun Yat-sen

- The Ideals That Ignited a Nation

- The Struggles Against Qing Rule and Foreign Domination

- The Establishment of the Kuomintang and the Vision for China

- Sun’s Last Days: Illness and Political Turmoil

- March 12, 1925: The Death of the Father of Modern China

- The Immediate Shock Across Beijing and Beyond

- Mourning a Nation: Public Response and National Grief

- The Power Vacuum and Political Implications

- The Legacy of Sun Yat-sen: Hero or Politician?

- How Sun’s Death Altered the Trajectory of China’s Revolution

- Reflections from Contemporary Figures and Historians

- The Cult of Personality: Memorials and Mythmaking

- The Global Resonance of Sun Yat-sen’s Passing

- Beijing’s Transformation After 1925: Remembering Sun

- The Long Shadow: Sun Yat-sen in Modern Chinese Memory

- Lessons from 1925: Nationalism, Revolution, and Leadership

- The Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum: A Shrine for the Ages

- China at a Crossroads: How Death Became the Dawn

- Conclusion

- FAQs About Sun Yat-sen’s Death and Its Impact

- External Resource

- Internal Link

On the morning of March 12, 1925, the air in Beijing was heavy — not with the crush of crowds or the stirrings of commerce, but with a quiet, somber weight that seemed to wrap the ancient city in a cloak of mourning. Streets ordinarily vibrant with life seemed hushed, as if the very heartbeat of the nation had suddenly faltered. This was the day when Sun Yat-sen, the towering revolutionary figure often called the “Father of Modern China,” passed away. At the age of 58, Sun succumbed to liver cancer in a foreign yet politically charged city, far from his birthplace but at the very center of China’s political maelstrom. His death was not only the loss of a man but the closing of an era — a fracture in China’s unpredictable path toward modernity and unity that would send ripples across the continent and the world.

Beijing of 1925 was a city caught between dynastic ghosts and republican dreams, where warlords jostled for control amid the fading glories of the Qing dynasty’s legacy. It was a capital knowing the weight of internal divisions and foreign encroachments, and into this crucible stepped a man whose vision of China was as radical as it was inspiring. Sun Yat-sen’s passing triggered a chain of political uncertainty, grief, and reflection. But to truly measure the magnitude of this moment, we must voyage back through the currents of history to understand the man whose life and death were intertwined with the fate of a country.

1. The Waning Twilight of a Revolutionary: March 12, 1925

The dawn broke over Beijing with a pallid sun, muted and shrouded in the city's winter haze. The solemnity of the day was palpable; government officials, revolutionaries, and ordinary citizens alike moved slowly, caught in a collective act of mourning they barely fully comprehended. It was not merely the death of an individual—Sun Yat-sen was the embodiment of a restless dream, a dream that had electrified a nation riddled with despair and foreign domination. When news of his passing spread, it spawned a quiet chaos—tears, stunned silence, whispered prayers.

This day was the culmination of Sun’s relentless battle against the political fragmentation and foreign subjugation that defined China after the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911. His death left a vacuum that would test his successors and the fragile ideals they carried forward. It was as if the revolution itself was momentarily paused, breathing in a bittersweet inhale of hope and uncertainty.

2. Beijing in the Early 1920s: A City on the Edge

Beijing in 1925 was barely recognizable from the seat of empire it once had been. The ancient capital struggled under the weight of internal chaos and external pressure. The city bore the scars of the collapse of imperial rule in 1911, followed by years of warlordism, political factionalism, and foreign interference. The streets were a mosaic of tradition and upheaval—imperial palaces shadowed by foreign legations, hawkers selling newspapers alongside soldiers bearing modern weapons.

The Chinese Republic had been proclaimed for over a decade, yet true unity remained elusive. Forces gathered and splintered in a fractious struggle for power. Sun Yat-sen’s presence in Beijing was both a beacon and a challenge; the capital was the stage where old regimes fought desperately to preserve influence against his revolutionary vision. The city embodied the broader national crisis: torn between past and future.

3. Sun Yat-sen: The Man Who Shaped Modern China

To understand the profound impact of Sun Yat-sen’s death, one must first understand the man himself. Born in 1866 in Guangdong province, Sun was a figure of paradoxes — a Christian revolutionary influenced by Western education yet deeply rooted in Chinese nationalism. He was a doctor by initial training but soon became a fiery political activist obsessed with liberating China from the Qing dynasty’s decay and the shackles of imperialism.

Sun’s charisma and vision forged a path that was neither purely Western nor traditionally Chinese. His Three Principles of the People—nationalism, democracy, and livelihood—were revolutionary ideas designed to transform China into a modern nation-state. Over decades of insurrection and exile, Sun became the symbolic architect of a new China, often overshadowed by the chaos that followed his efforts.

4. From Birth to Revolutionary: The Journey of Sun Yat-sen

Sun’s early life was marked by an encounter with both the West and East. His family’s migration to Hawaii exposed him to missionary education, fueling his belief in progress and reform. Yet, he witnessed his homeland’s subjugation firsthand, kindling an irreversible commitment to overthrow the Qing dynasty.

By the late 19th century, Sun had embraced revolutionary activities, founding secret societies and plotting uprisings. His efforts culminated in the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, which finally toppled the Qing dynasty and ended over two millennia of imperial rule. But victory was incomplete and fragile, as regional warlords and foreign powers scrambled to fill the void.

5. The Ideals That Ignited a Nation

Sun’s ideology was personal but also panoramic. The Three Principles were his blueprint for China’s rebirth:

- Nationalism: To unify the fractured Chinese nation against imperialist domination and internal disunity.

- Democracy: To establish a government accountable to the people, rejecting both absolutism and corruption.

- Livelihood: To promote social welfare and economic equity, ensuring the population's basic needs.

Though simple in aspiration, these principles were revolutionary in China’s fractured political landscape. They galvanized support and galvanized opposition alike, painting Sun as both a visionary and a threat.

6. The Struggles Against Qing Rule and Foreign Domination

Sun’s life was a series of confrontations: with the Qing dynasty’s decay, with foreign imperialists carving spheres of influence across China, and with competing Chinese factions that resisted his vision. His revolutionary campaigns often ended in exile or failure, but they spread the seeds of republicanism and nationalism widely.

His alliances—sometimes uneasy—with groups like the Communists and the Soviet Union shaped early Chinese politics. Yet these alliances were fraught and unstable, foreshadowing internal divisions that would outlive his death.

7. The Establishment of the Kuomintang and the Vision for China

Central to Sun’s legacy was the creation of the Kuomintang (KMT), the Nationalist Party. This organization aimed to unite China under a centralized, republican government aligned with Sun’s principles. The KMT became the vehicle for China’s political modernization and a rival to burgeoning communist forces.

Sun’s leadership fused military struggle with ideological propagation, embodying hope for a country torn apart by warlords and poverty. His death would leave the KMT grappling for coherence, as factions tugged in different directions.

8. Sun’s Last Days: Illness and Political Turmoil

Sun Yat-sen’s final years were shadowed by declining health and relentless political struggle. Diagnosed with liver cancer, his physical strength waned even while his political resolve endured. He moved strategically among southern Chinese cities and Beijing, rallying support for the Northern Expedition—a campaign to unify China under the KMT’s banner and defeat warlords.

Yet political intrigue and factionalism deepened, making his position tenuous. Despite his illness, he remained the symbolic glue holding diverse revolutionary factions together.

9. March 12, 1925: The Death of the Father of Modern China

At around 3 a.m. on March 12, 1925, Sun Yat-sen breathed his last in a hospital in Beijing. The news struck like thunder. Sun had died quietly, but the emotional and political tremors were deafening. Doctors confirmed liver cancer, and the man who had fought tirelessly for China’s rebirth now lay motionless.

The city reacted almost immediately—government offices lowered flags; telegrams were sent across provinces and abroad. Sun’s death pulled at the fragile threads of national unity, stirring both mourning and anxiety.

10. The Immediate Shock Across Beijing and Beyond

Within hours, crowds gathered in Beijing’s streets, some silent, others shouting, some clutching remnants of posters or newspapers praising Sun. The foreign press caught wind of the event, broadcasting a different narrative of China’s uncertain future.

In southern China, where Sun’s base was stronger, the mood was more explosive, with spontaneous demonstrations. Political allies and rivals alike scrambled to position themselves, aware that Sun’s mantle was suddenly up for grabs.

11. Mourning a Nation: Public Response and National Grief

The death of Sun Yat-sen was deeply personal for many Chinese who had seen in him not just a political leader but a symbol of hope. Poetry sprung up, eulogies were published, and mourning ceremonies spanned the provinces.

One anonymous Cantonese woman wrote, “He was the sun that never set on our hearts.” Yet mourning was also political—every faction sought to claim Sun’s legacy or discredit others by invoking his memory.

12. The Power Vacuum and Political Implications

Sun’s passing exposed fault lines within the KMT and between Chinese political powers. The absence of a unanimous successor led to factionalism, with Chiang Kai-shek rising prominently but not without contest.

The Kuomintang itself teetered between cooperation and conflict with Communist factions, sowing the seeds for the eventual split and civil war. China’s precarious balance of power entered a phase of intensified turbulence.

13. The Legacy of Sun Yat-sen: Hero or Politician?

Sun Yat-sen’s complex legacy defies simple categorization. To some, he was a saintly figure, a martyr for the Chinese nation. To others, a flawed leader whose ideals were too ambitious or who lacked the political machinery to enforce them.

Historian Julia Lovell suggests, “Sun’s greatness lay not merely in conquest, but in inspiration, in the imagination of a new China.” The myth and the man remain intertwined, shaping narratives up to this day.

14. How Sun’s Death Altered the Trajectory of China’s Revolution

Without Sun’s unifying presence, China’s revolution fractured decisively. The Northern Expedition would proceed under Chiang Kai-shek, but the fragile alliances unraveled. The civil war between Nationalists and Communists gained intensity, plunging China into decades of conflict.

Moreover, foreign powers recalibrated their strategies, sensing opportunity in the ensuing disorder. Sun’s death was a catalyst ushering in deeper political fragmentation but also eventual transformation.

15. Reflections from Contemporary Figures and Historians

Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek remarked, “Though the master has passed, the revolution must march on with unwavering steps.” Mao Zedong noted years later, “Sun Yat-sen was a guiding light, even if the path was long and treacherous.”

Western observers often viewed Sun’s death as the symbolic end of China’s hopeful republican experiment, setting the stage for the conflicts that would define the 20th century.

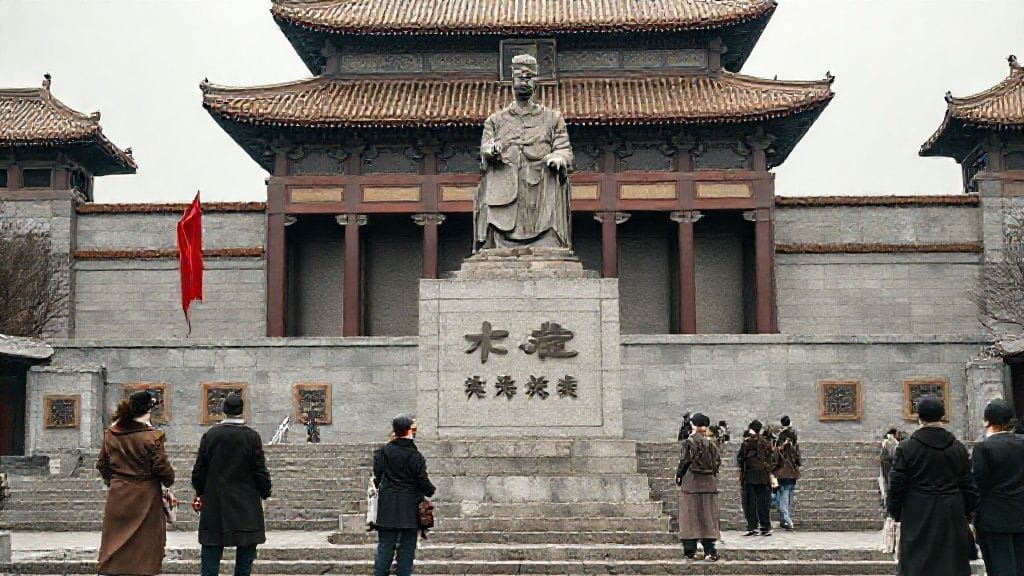

16. The Cult of Personality: Memorials and Mythmaking

In the years following his death, Sun Yat-sen was enshrined in memorials, statues, and mausoleums, most famously in Nanjing. These served not only as homages but as political tools—both Nationalists and Communists claimed him as forefather.

The veneration of Sun shaped Chinese political culture, turning the man into legend, often blurring historical reality with ideology.

17. The Global Resonance of Sun Yat-sen’s Passing

Sun’s death rippled beyond China’s borders. Asian nationalists regarded him as a revolutionary paragon; the West saw the potential collapse of a new republic. His vision influenced independence movements and anti-colonial struggles worldwide.

In diplomatic circles, his death signaled uncertainty, prompting cautious reassessments of China’s future.

18. Beijing’s Transformation After 1925: Remembering Sun

Beijing itself became a city marked by Sun’s memory. Streets were renamed; public spaces dedicated; textbooks chronicled his life and death as foundational.

Yet Beijing’s role as a political battleground intensified post-1925, the site of turbulent contests for power that echoed Sun’s unfinished revolution.

19. The Long Shadow: Sun Yat-sen in Modern Chinese Memory

In both the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan, Sun remains a unifying figure, transcending political divides. His image adorns currency, textbooks, and political rhetoric, symbolizing national unity and republican ideals.

Sun’s death in 1925 is commemorated annually, a solemn reminder of the sacrifices made for China’s transformation.

20. Lessons from 1925: Nationalism, Revolution, and Leadership

Sun Yat-sen’s death teaches us the fragility of revolutionary movements without strong, unifying leadership. It highlights the tensions between ideals and realpolitik — the challenges of transforming vision into durable governance.

His life and death underscore the complexities inherent in nation-building, especially amid foreign pressure and internal discord.

21. The Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum: A Shrine for the Ages

Located in Nanjing, the Mausoleum stands as a testament to his enduring legacy. Completed in 1929, it draws millions of visitors annually, a pilgrimage site for those seeking inspiration from the founder of modern China.

The architecture blends traditional and modern elements reflecting Sun’s synthesis of East and West.

22. China at a Crossroads: How Death Became the Dawn

Sun Yat-sen’s death was not an end but a beginning. It marked the transition from revolutionary idealism to turbulent power struggles, which ultimately shaped the China emerging mid-century.

In tragedy, there was seed for renewal—a reminder that leadership is transient but ideas, when rooted deeply, can outlive men.

Conclusion

Sun Yat-sen’s death on that cold March day in 1925 was at once a deeply personal loss and a seismic political event. It closed a chapter on China’s first revolutionary dream while opening another filled with uncertainty, conflict, but also the promise of unity. The man who had dared to imagine a modern, sovereign China left behind a legacy that continues to inspire and challenge. His passing illuminated the precarious nature of revolutionary leadership — how one life can both ignite a nation’s hope and expose its vulnerabilities.

As Beijing and all of China grappled with his absence, Sun Yat-sen’s spirit became a lodestar—not just for those who knew him personally but for generations seeking to understand what it means to build a nation out of turmoil and aspiration. His vision of nationalism, democracy, and livelihood remains etched into the very fabric of China’s modern identity, a reminder that even in death, the sun never truly sets on the dreams of those who dare to change history.

FAQs

Q1: What caused Sun Yat-sen’s death?

Sun Yat-sen died of liver cancer on March 12, 1925, while staying in Beijing during a critical period of political transition in China.

Q2: Why was Sun Yat-sen in Beijing at the time of his death?

Sun was in Beijing to rally political support for the Northern Expedition and to consolidate revolutionary efforts against warlords and fragmentation.

Q3: How did Sun Yat-sen’s death affect Chinese politics?

His death left a leadership void in the Kuomintang, leading to internal conflicts and power struggles that shaped China’s subsequent civil war and political developments.

Q4: Who succeeded Sun Yat-sen as leader of the Kuomintang?

Chiang Kai-shek gradually emerged as the dominant leader after Sun’s death, leading the Northern Expedition and later the Nationalist government.

Q5: How is Sun Yat-sen remembered in China today?

Both Mainland China and Taiwan honor Sun as the “Father of Modern China,” commemorating his contributions to nationalism and republican ideals.

Q6: What was the significance of Sun’s Three Principles of the People?

They formed the ideological foundation for China’s republican revolution: nationalism to unify the country, democracy to govern it, and livelihood to improve social welfare.

Q7: Did Sun Yat-sen’s death lead to immediate changes in government?

While his death precipitated political upheaval, fundamental shifts occurred gradually, as competing factions vied for control in a fragmented China.

Q8: Where is Sun Yat-sen buried?

Sun Yat-sen is interred in the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum in Nanjing, an important cultural and historical site.