Table of Contents

- A Fractured Empire on the Brink

- The Shadow of Valerian’s Capture and the Crisis of the Third Century

- Mediolanum: Crossroads of Italy and Prize of Empires

- The Alamanni Advance: From the Rhine to the Po

- Gallienus Rallies: The Emperor Who Could Not Afford to Fail

- Mustering the Roman War Machine: Cavalry, Auxiliaries, and Militia

- Eve of Steel: The Night Before the Battle of Mediolanum

- Clash at the Gates: The Opening Phase of Battle

- The Cavalry Hammer: Gallienus’ Decisive Counterstroke

- Blood in the Fields: Aftermath on the Battlefield

- Securing Italy: Political Repercussions of Victory

- Gallienus Reconsidered: From Failed Heir to Reluctant Savior

- The Alamanni and the Limits of Roman Power

- Echoes Through Time: Memory, Sources, and Historiography

- Legacy of the Battle of Mediolanum in Military Thought

- Conclusion

- FAQs

- External Resource

- Internal Link

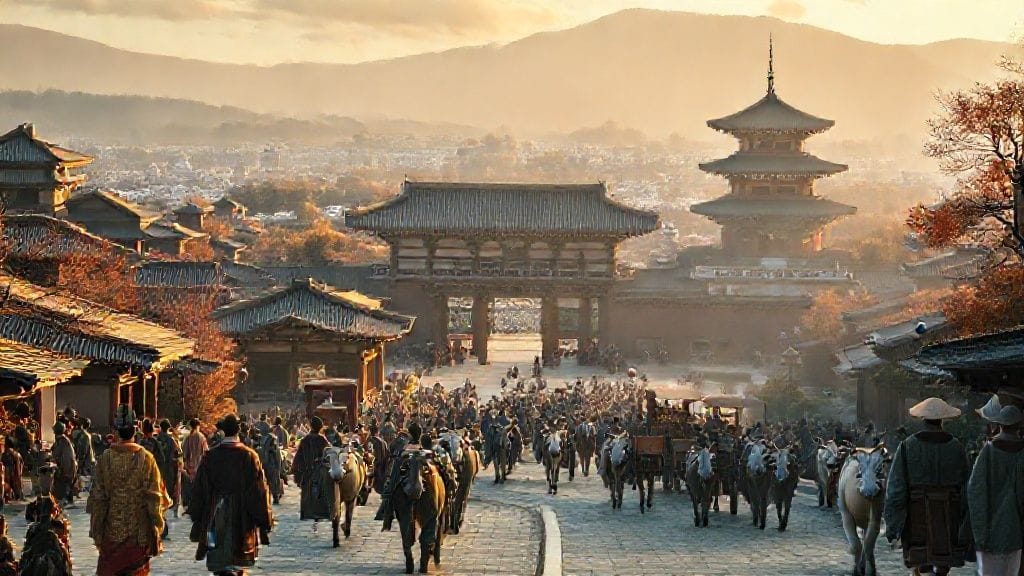

Article Summary: In 259 CE, at the very heart of northern Italy, the battle of mediolanum became a desperate gamble for the survival of the Roman Empire’s core provinces. The Alamanni, a loose confederation of Germanic warriors, had burst across the Rhine and the Alpine frontiers, threatening Mediolanum—modern Milan—and with it the symbolic and logistical center of Roman Italy. Emperor Gallienus, overshadowed by his father Valerian and scorned by later writers, threw his elite cavalry into a swift and risky campaign that culminated in this crucial clash. The article traces the empire’s wider Third-Century Crisis, the political chaos, economic breakdown, and military overstretch that shaped the stakes of the battle of mediolanum. It then reconstructs the approach to battle, the brutal fighting outside Mediolanum’s walls, and the tactical use of Roman horse to shatter the invading host. Yet behind the apparent Roman triumph lay deeper fractures: unstable frontiers, contested authority, and a society accustomed to emergency. Through narrative and analysis, we follow the human stories of soldiers, civilians, and rulers whose fates converged that year in northern Italy. Finally, the article explores how the battle of mediolanum has been remembered, reinterpreted, and sometimes minimized by historians, and why its legacy still speaks powerfully to themes of resilience, leadership, and the precariousness of imperial power.

A Fractured Empire on the Brink

The year 259 CE did not feel like a single year to those who lived through it; it felt like an acceleration, a tearing of time itself. The Roman world, for centuries a colossus that stretched from the misty isles of Britannia to the sun-baked deserts of Syria, was suddenly brittle. Emperors rose and fell with terrifying regularity, coins lost their value within a generation, and frontiers that had once seemed eternal lines on the map melted before waves of invaders and usurpers.

Into this atmosphere of dread came the looming confrontation that would later be known as the battle of mediolanum. To a Roman farmer in northern Italy, it was not “a battle” in the abstract. It was the sound of hooves on the roads that had carried wine and grain, the smoke of distant villages burning beyond the horizon, and the rumors—always rumors—of barbarians in places where no barbarians had ever dared to stand before. To a senator in Rome, it was another entry in a ledger of crises, threatening not only land and property but the old illusion that Italy itself was untouchable.

Rome had faced disaster before: Hannibal in the Second Punic War, rebellious generals, and civil wars. But this time felt different. Troubles did not come one by one; they came all at once. In the east, the Sasanian Persians were proving themselves equal, perhaps superior, rivals to Roman arms. In the west, along the Rhine and Danube, Germanic confederations—Alamanni, Franks, Goths—were testing the limits of the empire’s resolve. Within only a few years, emperors would be slain on the battlefield, captured alive by enemies, or murdered by their own soldiers.

By the late 250s, this maelstrom had acquired a name among modern historians: the Crisis of the Third Century. To those living it, it had no name; it was simply life. Plague had swept through the empire some decades earlier, sapping manpower and shaking faith in the old gods. Taxation grew heavier as the state tried to pay its soldiers and secure its fortresses; coinage was debased, its silver scraped away in a desperate effort to stretch shrinking resources. Local communities, especially in the western provinces, began to look first to their own survival rather than to the distant and sometimes invisible authority of the emperor.

And yet, even amid the chaos, the empire retained pockets of strength. The roads still radiated from the old Republican heartland, binding Italy and the western provinces together. Granaries and workshops still functioned. The Roman army, though stretched thin and increasingly reliant on hastily raised troops, retained its hard core of professionals, veterans who carried in their bodies the memory of drill, discipline, and victory. It was this combination—imperial fragility and residual military might—that set the stage for the events at Mediolanum.

When word arrived that a large Alamannic force had broken into northern Italy, it did not feel like a peripheral crisis. It felt like sacrilege. Italy, long shielded from full-scale barbarian incursions since the age of Augustus, was supposed to be the sacred core, inviolate, the land that sent legions out but did not receive foreign war in return. Now that illusion was shattering. The response of Emperor Gallienus, who bore much of the burden while his father Valerian was engaged in the east, would determine whether the empire’s heartland could be saved—or whether the Third-Century Crisis would reach a point of no return.

The Shadow of Valerian’s Capture and the Crisis of the Third Century

To understand the weight pressing upon Gallienus as he rode toward Mediolanum, one must enter the shadow cast by his father, Valerian. When Valerian was proclaimed emperor in 253 CE, many hoped that a seasoned senator and commander might stabilize the empire. Instead, he found himself firefighting on multiple fronts. The Persian king Shapur I was on the offensive in the east, and Valerian marched to counter him, taking with him significant eastern field forces. Gallienus, his son, remained largely responsible for the defense of the west.

By 259–260, the unthinkable happened. Near Edessa, in Mesopotamia, Valerian suffered a catastrophic defeat and was taken prisoner by Shapur. Roman sources tried to veil the humiliation, but the reality seeped through: the emperor of Rome, captured alive, paraded as a trophy by a foreign king. Later Christian authors, like Lactantius, would embellish cruel anecdotes about Valerian being used as a human footstool before being flayed, but even stripped of propaganda, the core fact was shattering. The office of emperor, already bruised by repeated usurpations, had never suffered such an affront.

This disaster overlapped with and intensified the wider Third-Century Crisis. In the Balkans and Danube regions, Goths and other tribes raided deeply into Roman territory. In the west, the Franks were beginning to test the defenses of Gaul and even Hispania. The empire was beginning to fracture politically. Local strongmen, often generals appointed to guard specific frontiers, were tempted to carve out their own semi-independent realms. Within a decade of the battle of Mediolanum, the so‑called Gallic Empire would emerge in the west under Postumus, and the Palmyrene regime would rise in the east. The idea of a single, unchallenged emperor ruling from Rome was growing more fragile by the month.

In this crumbling landscape, Gallienus stood at the center. Ancient authors, often senatorial and hostile to him, painted him as frivolous, more interested in pleasure or philosophy than power. Yet a closer reading—bolstered by modern scholarship—reveals a different figure: a ruler constantly on campaign, fighting in the Balkans, the Rhine, and Italy, improvising new military structures, especially cavalry forces, to respond rapidly to mobile barbarian incursions. The battle of mediolanum would be one of the most striking tests of this new, mobile strategy.

Italy’s vulnerability was the most frightening symptom of the times. For centuries, the empire’s defensive depth had allowed Italy to function as a secure rear area. Troops could be recruited, trained, and dispatched outward. The armies that Hannibal and later invaders had once brought into Italy seemed like distant memories, instructive but not threatening. The Third-Century Crisis reversed this sense of security. With frontiers destabilized and legions pulled in multiple directions, the line between “frontier” and “interior” blurred. And when the Alamanni crossed that blurred line, alarms rang from the Alpine foothills to the city of Rome itself.

Modern historians have debated the exact year and sequence of events. Some place the Alamannic invasion of northern Italy squarely in 259, others blend it into the campaigns of 260, as the chronology is muddied by conflicting sources and the change of regnal years. Yet they largely agree on the essentials: a sizable Alamannic force exploited weaknesses along the upper Rhine and transalpine routes, broke into Italy, and forced Gallienus to march to confront them near Mediolanum. The crisis of the Third Century had, literally, come home.

Mediolanum: Crossroads of Italy and Prize of Empires

Mediolanum was not yet the imperial megacity that Milan would later become under Diocletian and Constantine, but by 259 it was already one of the jewels of northern Italy. Its very name—“the place in the middle of the plain”—captured its geographical significance. It sat at the nexus of roads and trade routes that bound northern Italy to the Alpine passes and beyond to Gaul and the Germanic frontier. Whoever commanded Mediolanum could move armies swiftly across the Po Valley, supply them from rich agricultural lands, and coordinate communication with Rome and the wider Mediterranean.

Archaeological evidence and literary references suggest a thriving urban life: forums bustling with merchants, temples where the city’s elite made offerings to Jupiter and other gods, workshops producing textiles and metal goods, and an ever-present military edge. The city’s location meant it frequently hosted detachments of troops, officers on their way to and from frontier posts, and the logistical apparatus needed to feed and arm men on campaign. Though its walls were not yet as imposing as those of later centuries, it was not a soft target.

Yet, for all Mediolanum’s strengths, its proximity to the Alps made it a frontline city the moment the frontier system failed. The roads that carried tax grain and commerce could also carry invaders. An Alamannic force that slipped through or broke past the border defenses could be in the Po Plain with terrifying speed. And once there, the open terrain favored large cavalry maneuvers and rapid raids. The same Roman engineering marvels—roads, bridges, and way stations—that cemented imperial rule could be turned against the empire in a moment of weakness.

To the people of Mediolanum, the first reports of Germanic warbands in Italy must have sounded vague and distant. There had been raids before, after all, and the imperial army had always pushed them back. But when refugees began to arrive—merchants whose wagons had been seized, peasants with stories of burned villas and trampled fields—the city’s mood would have darkened. Local officials scrambled to reinforce gates, call in local militia, and send frantic messengers to the emperor’s headquarters. The battle of mediolanum, as we now call it, was in its early stages not only a military campaign but a race against fear and rumor.

Mediolanum’s elites would have grasped the wider implications immediately. If the city fell or was badly sacked, confidence in imperial protection would plummet throughout Italy. Other cities, from Verona to Ravenna, would feel exposed. Landowners might arm their own retainers or seek private arrangements with marauding groups rather than relying on distant imperial commands. In a crisis-ridden empire, political perception mattered almost as much as actual troop numbers. A visible failure in Italy could embolden usurpers, regional governors, or foreign kings to press their advantage.

Thus, Mediolanum was more than a physical prize. It was a symbol of whether Rome could still safeguard her core. When Gallienus decided to confront the Alamanni there, he was not merely choosing suitable terrain; he was staking his rule, and the psychological cohesion of the empire, on the outcome.

The Alamanni Advance: From the Rhine to the Po

The Alamanni were not a single tribe in the way a Roman might imagine a “people”; they were a coalition, a confederation of Germanic groups that had coalesced along the upper Rhine over the preceding centuries. Their very name, possibly meaning “all men” or “men of all kinds,” hinted at this composite nature. By the mid‑third century, they had become one of Rome’s most persistent western antagonists, an agile and aggressive neighbor constantly probing the frontier.

The reasons for their incursion into Italy in 259 were layered. On the surface, there was the lure of plunder: Italy was rich, and its towns and villas promised more bounty than many border districts. But beneath that were deeper currents: population pressures in the trans-Rhenish regions, shifting power balances among Germanic groups, and perhaps a keen perception that Roman defenses were in disarray. News of Valerian’s difficulties in the east and ongoing troubles in Gaul and along the Danube would not have been entirely unknown beyond the frontier. Traders, deserters, and scouts conveyed fragments of information that sharp-eyed leaders could interpret as opportunity.

We do not know the precise size of the invading Alamannic host, but ancient accounts imply a considerable force, large enough to batter aside, outmaneuver, or bypass Roman garrisons along parts of the Rhine frontier. Once across, they likely split into bands, some raiding, others scouting, converging again when larger resistance loomed. The path into Italy could have led through the upper Rhine valleys into the Alpine passes, perhaps the Brenner or routes through Raetia, where the empire’s garrisons had been weakened by the chronic need to dispatch troops elsewhere.

As they descended into the northern Italian plains, the Alamanni entered a landscape unlike their homelands: a patchwork of carefully tended fields, vineyards, walled villas, and intersecting roads. To the local population, these warriors—tall, often fair-haired, armored in a mix of mail, leather, and furs—must have seemed like figures torn from the primal forests of the north. They brought with them both infantry and cavalry; Germanic horsemen, though not yet the armored cataphracts of later centuries, could move fast and strike deep. The Roman notion that Germany was a land of pure infantry was more stereotype than reality by this point.

Their progress was marked by fire and fear. Villas that could not be defended were stripped and burned, storehouses looted. Temples were violated, not necessarily out of ideological hatred but simply as repositories of wealth. Local militias fought where they could, sometimes successfully ambushing smaller bands, but against the main Alamannic force they stood little chance. The road to Mediolanum, in those weeks, would have been lined with smoke columns and scattered corpses.

Yet the Alamanni were not advancing into a void. Scouts would have reported the movement of Roman cavalry columns, the hurried assembling of a field army. They may have heard the name Gallienus whispered by captives, the emperor who was said to ride with his horsemen rather than supervise from a palace. The Alamanni had faced Roman counterattacks before along the frontier, but an imperial-led concentration in Italy itself was a different matter. Still, to retreat empty-handed would squander the momentum they had built. Thus they pressed on toward Mediolanum, prepared for a confrontation whose scale they may not have fully grasped.

Gallienus Rallies: The Emperor Who Could Not Afford to Fail

In Gallienus we meet a figure long obscured by hostile sources and the sneers of later historians. The senatorial class, from which many of our texts derive, disliked him; he marginalized them in military command, promoted equestrian officers, and relied on personal loyalty rather than old aristocratic networks. Christian authors writing under Constantine’s dynasty would later contrast his supposed frivolity with the piety of later rulers. Yet when we look at the bare facts of his reign, particularly his response to invasions like the one that culminated at the battle of mediolanum, another image emerges: that of a pragmatic, battle-hardened emperor who spent much of his life in the saddle.

By the late 250s, Gallienus had already fought along the Rhine and Danube, pushing back various incursions. He had learned the hard way that the legions, as they had been structured in earlier centuries, were often too slow and rigid to deal with fast-moving confederations like the Alamanni. In response, he seems to have fostered the growth of a powerful central cavalry reserve—mobile striking forces that could be rushed to threatened sectors of the empire. Some scholars see in this the earliest seeds of the mobile field armies (comitatenses) that would become a hallmark of the later Roman Empire.

The Alamannic penetration into Italy confronted him with a nightmare scenario: an enemy within the core provinces, too far inside to be easily contained at fortified lines. To delay was to allow them to ravage more territory and potentially threaten cities far south of the Po. Gallienus therefore gathered what he could: detachments from frontier legions, provincial auxiliaries, and, crucially, his elite cavalry units. Especially important were the heavily armed and highly trained horsemen stationed near Milan and other key nodes—perhaps the nucleus of what would later be known as the imperial cavalry guard.

One can imagine the emperor’s council of war, perhaps held in a hastily repurposed hall in northern Italy. Maps, or rather wax tablets and mental geography, would be consulted. Messengers arrived dust-covered, bearing conflicting reports about the Alamanni: here a success by local forces, there a town burned. Time was the enemy as much as the invaders were. Gallienus needed to predict where the Alamanni would move next and place himself between them and their likely objectives. Mediolanum, with its central location and resources, was a natural anchor point for his strategy.

He also had to think politically. News of Valerian’s capture had not yet fully sunk in across the empire, but the emperor knew—or at least feared—what had happened in the east. Even if reports were incomplete, the mere possibility that his father was lost increased the pressure on him. Failure in Italy, where senators and wealthy landowners had their estates and families, could trigger a cascade of desertions and rebellions. Success, by contrast, might shore up his legitimacy and prove that the empire, though wounded, could still defend itself.

As the Roman army marched northward, it would have been a strange and varied sight. Veterans with weathered faces and patched armor marched alongside fresh recruits, some perhaps recently levied from Italian towns or hastily gathered from city cohorts. Standards bearing the familiar eagles fluttered next to newer insignia of elite cavalry units. Gallienus himself, clad in a cuirass and enveloped in a general’s cloak, was no distant figure. He was, according to the more credible strands of tradition, an emperor who rode at the head of his columns, visible to the men whose loyalty he depended on.

The march toward Mediolanum, therefore, was more than a logistical movement. It was a performance of imperial presence, a traveling assertion that Rome still had a leader and that this leader was willing to risk his own life in the field. For the soldiers, weary of endless crises, this may have rekindled some measure of confidence. For Gallienus, there could be no retreat. If he failed outside Mediolanum, he might not only lose a battle—he might lose the empire.

Mustering the Roman War Machine: Cavalry, Auxiliaries, and Militia

The army that coalesced around Gallienus near Mediolanum was not the pristine machine of Augustus’ day. It was, instead, a patchwork—yet still deadly when wielded by an experienced hand. At its core stood units drawn from the old legions, disciplined infantry who understood formation fighting and the brutal arithmetic of close combat. Around them clustered auxiliary cohorts, many of them originally recruited from non-Italian provinces: archers from the East, light infantry from the Balkans, specialized horsemen from the Danubian and Gallic regions.

The distinguishing feature of Gallienus’ forces, however, was the emphasis on cavalry. Contemporary and near-contemporary accounts hint at a large mounted contingent, and later sources, though filtered through time, associate him with the development of elite cavalry units stationed in or near Mediolanum. These horsemen, equipped with lances, swords, and sometimes bows, represented a flexible instrument. They could scout, harry enemy foraging parties, and, when massed, deliver a powerful shock charge against less organized foes.

In addition to these regular forces, local militia and hastily organized citizen troops likely played a supporting role. Italian landowners had no wish to see their estates burned, and city councils could be surprisingly resourceful in raising men for local defense. Armed with whatever equipment could be found—old helmets, hunting spears, even tools repurposed as weapons—these men would not decide the battle on open ground, but they could keep order inside the city, guard supply lines, and free up professional soldiers for frontline duty.

Logistics, too, had to be hurriedly arranged. An army living off the land risked alienating the very population it was trying to protect, so Gallienus’ staff would have pushed Mediolanum and neighboring communities to provide grain, fodder, and quarters. The city’s granaries were emptied with grim determination; bakers worked through the night turning grain into bread for marching men. Artisans repaired armor and weapons, hammered out replacement spearheads, and shod horses with new iron shoes so they could gallop reliably across the plains.

It is easy to imagine the tension in the makeshift camps outside the city walls in those days leading up to the battle of mediolanum. Soldiers cleaned weapons, shared rumors, and sharpened their own bravery with gruff jokes. Veterans, who had fought Germans before along the Rhine, offered advice to younger men: hold the line, watch their charges, trust your officers. Centurions walked the camp streets, inspecting kit and barking orders to maintain discipline. Somewhere, perhaps under a pavilion lit by flickering oil lamps, Gallienus and his senior commanders debated the precise plan of engagement.

Every choice carried risk. If he advanced too far from Mediolanum in search of the enemy, Gallienus might leave the city exposed to a sudden thrust. If he clung too close to its walls, the Alamanni could ravage the surrounding countryside at will. The solution he sought lay in a balance: use Mediolanum as a secure base for supplies and communications while drawing the Alamanni into a battle on ground favorable to Roman tactics, especially the decisive use of cavalry. That, in turn, would require nerve—not only from the emperor but from every man who would stand in the line of battle when the day came.

Eve of Steel: The Night Before the Battle of Mediolanum

The night before a battle is always thick with unspoken fears. Outside Mediolanum, under the stars of the Italian sky, thousands of men lay listening: to the rustle of tents, the snorting of horses, the distant murmur of sentries moving along the perimeter. Somewhere beyond the dark horizon, the Alamanni were encamped too, their own fires dotting the plains, their own warriors wondering whether tomorrow would bring plunder and triumph or death far from home.

Within Gallienus’ camp, the rituals of preparation unfolded. Priests and augurs examined the entrails of sacrificed animals, searching for omens. Did the liver appear healthy? Did the heart show any unusual marks? In an age that blended rational campaigning with deep religious sensibility, a favorable sign could bolster morale as effectively as a stirring speech. Gallienus, raised in the old traditions yet ruling in radically changing times, would not have neglected such rites. He needed the gods—or at least the appearance that the gods were with him.

Officers made last-minute inspections. Saddles were checked, girths tightened, weapons tested. Shields were examined for weak spots, and pila (heavy javelins) were stacked where infantry could easily reach them. Surgeons and their assistants, the unsung professionals of the Roman army, laid out their tools: scalpels, bandages, cauterizing irons. They knew what dawn would bring.

The emperor might have walked among his men, as so many of his predecessors had done. Perhaps he stopped before a line of cavalrymen, their helmets reflecting the torchlight, and spoke briefly: of Italy’s ancient glory, of their families who slept behind the city’s walls, of the shame that would follow if they failed. Roman soldiers responded not only to fear and pay but to honor and shared identity. To frame the coming clash as a fight for the very heart of the empire was to give it a meaning that could steady shaking hands.

Across the no‑man’s‑land separating the camps, Alamannic leaders were making their own calculations. For them, the presence of an emperor at the head of the Roman army was both a danger and an opportunity. Defeating imperial forces in the field, with the emperor present, could yield enormous prestige among neighboring tribes and confederations. But it also meant they faced the best concentrated resistance Rome could quickly assemble. They would have discussed tactics: how to blunt the Roman cavalry, how to avoid being pinned and enveloped, how to maximize the shock of their own warriors’ charges.

In the dark, wind brushed across the plain, smelling faintly of smoke, earth, and the metallic tang of anticipation. Men rolled in their cloaks, eyes closed but minds restless. Some whispered prayers to Jupiter or Mars; others appealed to more local or personal deities; still others muttered to the shades of their ancestors. Even in an age of brutal familiarity with death, the knowledge that tomorrow’s sun might be the last a man ever saw was impossible to ignore.

And yet, there is always a strange stillness when the final preparations are complete. Swords are sharpened; plans are laid; sentries are posted. The army becomes like a drawn bow a heartbeat before release. Somewhere in that quiet, Gallienus must have looked out toward the darkness hiding the Alamanni and understood that the coming hours would shape not only his own legacy but the fate of Italy itself.

Clash at the Gates: The Opening Phase of Battle

Dawn came with the gray softness of Italian light spreading over the fields around Mediolanum. The city’s walls, not yet the massive structures of the late empire, nevertheless loomed as a reminder of what was at stake. As the mists burned away, the two forces began to form their lines, the choreography of battle unfolding with practiced precision on one side, fierce spontaneity on the other.

The Alamanni, according to the pattern of many Germanic warbands, likely arranged themselves in dense masses of infantry interspersed with more lightly equipped warriors and flanked by cavalry where possible. Their warriors favored long spears, swords, and large shields; some wore chainmail captured or traded from Romans, others leather or thick tunics. Their strength lay in ferocity, in the shock of a massed charge and in the ability of smaller bands to exploit gaps, bypass flanks, and sow confusion.

The Romans, by contrast, deployed in a more segmented formation. Infantry formed the backbone, arranged in cohorts that could support each other, their shields locking and overlapping like scales. In front, screens of skirmishers—perhaps light-armed auxiliaries with javelins and slings—moved out to harass the enemy advance. On the flanks and held somewhat back, Gallienus placed his cavalry: the weapon he intended to use not at the outset but at the decisive moment.

Trumpets sounded. Standards lifted. The battle of mediolanum, in its first phase, began as so many ancient battles did: with a creeping advance followed by sudden acceleration. Skirmishers darted forward, loosing missiles, then fell back behind their own main line as Germanic war cries began to rise. The ground trembled under the first concerted push of the Alamannic infantry.

To the Roman soldiers in the front ranks, the sight would have been both familiar and terrifying: a wall of men, fierce-eyed, hair flying, shields banging, surging forward. Arrows and javelins arced overhead from both sides, some striking shields with dull thuds, others with wet, shocking impacts into flesh. Officers shouted to hold formation, to keep shields high and spears steady.

When the clash finally came, it was not a neat collision but a grinding collision of human masses. The first ranks absorbed the shock, men staggering, feet shoving for purchase in the churned earth. Swords flashed between shields, spears jabbed over the top. The Roman line bent but, crucially, did not break. Centurions stepped into gaps, dragging wounded men back and pushing reserves forward. Their vine staffs, so often used for discipline in camp, now served as prods to keep the living wall intact.

The Alamanni pressed hard, perhaps hoping to smash through quickly before Roman discipline could assert itself. For a time, it might have seemed as if the mass of Germanic warriors would overwhelm the thinner Roman infantry screen. Clouds of dust, the mingled cries of pain and encouragement, and the metallic ring of weapons created a chaos in which no one man could see the whole field. Only Gallienus and his senior officers, positioned behind the lines and riding along the front, could interpret the shifting currents.

It was in this crucible that the emperor’s plan took shape. He had not committed his cavalry en masse at the outset. Instead, he waited, watching for signs: where the Alamannic advance slowed, where their flanks stretched thin, where isolated clusters of Roman infantry might be at risk of encirclement. Only once he understood the pattern of the enemy’s momentum would he unleash the blow he had designed this army to deliver.

The Cavalry Hammer: Gallienus’ Decisive Counterstroke

At some point in the mid-morning, the battle of mediolanum reached its tipping point. The Alamanni, having thrown themselves again and again against the Roman infantry, were fully committed. Their front ranks were engaged in bitter hand-to-hand fighting; their reserves, drawn forward in the hope of widening a breach, had less depth left to respond to threats on the flanks. Dust rose in a thick haze, obscuring precise movements. This was the moment Gallienus had been waiting for.

Signals flashed across the Roman rear: trumpet calls, raised standards, perhaps even prearranged colored flags. On the wings, the cavalry units began to move. At first, the motion was slow, rank aligning with rank, horses snorting and tossing their heads as bits were gathered. Then, as commands barked down the line, the trot became a canter, the canter a gallop. The ground shook anew, this time under the disciplined advance of Roman horsemen.

One can almost hear the sound building: the rhythmic thunder of hooves, the creak of saddles, the clatter of weapons against armor. Lances tilted forward; swords were drawn; riders leaned low, eyes fixed on the shifting silhouettes of the Alamannic flanks. For the warriors on those flanks, the sudden appearance of a massed cavalry charge must have been chilling. They had expected Roman infantry and perhaps some scattered horse, but this was something else: a concentrated hammer aiming to smash them where they were least prepared.

The first impact was catastrophic. Roman cavalry, especially those elite units Gallienus had nurtured, combined speed, weight, and coordination. Against loosely ordered infantry or unprepared horsemen, such a charge could rip open formations like cloth. Here, on the fields outside Mediolanum, they crashed into the Alamannic flank with brutal force. Men were ridden down, spears splintered, shields torn aside. Some Alamannic fighters tried to anchor themselves, forming ad hoc shield walls, but the momentum was against them.

Once the initial shock had broken the flank, the cavalry did not simply ride through and away. They wheeled, reformed, and charged again and again, turning a breach into a rout. Gallienus, if we trust the more favorable strands of tradition, was in the thick of it, directing charges, pointing out targets, and rallying any wavering Roman units. The emperor who had been mocked by some as an aesthete and dilettante now showed himself as a battlefield commander.

As the Alamannic flank buckled, panic began to ripple inward. Warriors in the main body, already exhausted from prolonged fighting against the Roman infantry, now found their comrades collapsing on one side, pursued by horsemen who seemed to come from everywhere. Attempts to realign, to pivot the entire mass to face the new threat, faltered under pressure. Communication across such a chaotic battlefield was poor; by the time orders reached rear units, the situation had already worsened.

On the opposite flank, Roman cavalry moved as well, pinning down or driving off any Alamannic horse that might have stabilized the line. What had begun as a frontal slog now morphed into a partial encirclement. The Roman infantry, feeling the pressure ease as the enemy’s will faltered, pressed forward with renewed vigor. Standard-bearers advanced, centurions shouted for one last push, and the grim work of turning resistance into flight began.

Ancient sources, sometimes prone to exaggeration, speak of the Alamanni being “slaughtered” in vast numbers near Mediolanum. While the exact casualty figures are unknowable, the tactical shape of the battle suggests a heavy defeat. Once a force like the Alamannic host broke and attempted to flee, especially in relatively open terrain, mounted troops could wreak havoc on their retreating ranks. Men burdened with loot or weakened by hours of fighting were easy prey for fresh cavalryman wielding sword and spear.

From a military history perspective, this phase of the battle of mediolanum has drawn interest for what it reveals about Roman adaptation. As scholars like J.C.N. Coulston and Hugh Elton have argued in broader studies of Roman warfare, the third century saw a marked evolution in the prominence and role of cavalry. Here, Gallienus demonstrated that a well-timed, large-scale cavalry intervention could decisively turn a battle against migratory or raiding forces whose strength lay in initial shock, not sustained, coordinated maneuver. It is not too much to say that Mediolanum foreshadowed the mixed infantry–cavalry tactics that would dominate late Roman battlefields.

Blood in the Fields: Aftermath on the Battlefield

When the killing finally ebbed, the fields outside Mediolanum were a ruin of bodies, broken weapons, and trampled earth. The battle’s noise faded, replaced by the low moans of the wounded and the shouted commands of officers trying to restore order. Victory, even in Roman eyes, was never a clean thing. It was a carcass from which the living pulled whatever they could before it rotted: prisoners, captured arms, abandoned banners, and, grimly, the rings and trinkets that dead enemies no longer needed.

Gallienus’ immediate priorities were clear. First, he had to ensure that no significant Alamannic force remained intact enough to regroup. Cavalry detachments were sent in pursuit, but he would also have been wary of dispersing too many of his men in small groups that could be ambushed in wooded or uneven terrain. Some Alamanni, especially those who had disengaged early, likely slipped away into the countryside and eventually back toward the frontier. The shattered core, however, was destroyed as a coherent threat in Italy for the time being.

Second, there was the matter of his own army. Roman discipline demanded that units re-form, count their dead and missing, and secure the field. Burial details began their weary work, digging pits or cairns. Officers wrote reports for the imperial archives, perhaps inflated in their praise but studded with real details: which units had distinguished themselves, where the line had come close to breaking, how the cavalry had performed. Surgeons moved from man to man, trying to save limbs and lives where possible, murmuring quiet words as knives cut and fire seared wounds closed.

Among the Alamannic dead, Roman soldiers searched for leaders. Captured chieftains or the bodies of prominent warriors could be used as political symbols: paraded through Mediolanum, displayed as proof that the invaders had been not only repelled but humbled. Prisoners, when taken, faced uncertain fates. Some might be enslaved and scattered throughout the empire; others, especially younger men, could be forcibly recruited into auxiliary units, their martial skills turned to Rome’s service.

For the inhabitants of Mediolanum, the sight of Roman standards returning through the city gates, followed by weary but triumphant soldiers, must have brought an almost physical relief. The nightmare of an Alamannic sack had passed. Families who had spent the night huddled in temples or cellars emerged blinking into the light, listening eagerly for news. Stories spread quickly: of the emperor’s courage, of narrowly averted disaster, of miraculous feats by nameless soldiers on the line.

Yet behind the celebrations, there was mourning too. Some of those who had marched out with Gallienus had not returned. Their absence would be felt in households across Italy and the provinces that had furnished troops. The city’s streets, briefly festooned, would soon also echo with funerary processions. Marble monuments might later record the names of fallen officers, but the common soldier would be remembered only in the private grief of comrades and kin.

It is astonishing, isn’t it, how quickly human societies move from catastrophe to commemoration. Already, in the days following the battle of mediolanum, scribes and rhetoricians were crafting the narrative. Here, they would say, was proof that Rome, under Gallienus, could still strike hard. Here was a sign that the gods had not entirely abandoned the empire, that Italy remained under divine and imperial protection. In an age so hungry for reassurance, such a story was as valuable as any captured treasure.

Securing Italy: Political Repercussions of Victory

The victory at Mediolanum rippled outward far beyond the blood-soaked fields where the Alamanni fell. News traveled along the same roads the invaders had used, moving now as letters carried by imperial couriers, as boasts told by veterans in taverns, as official announcements read out in city forums. In Rome, the Senate, often wary and resentful of Gallienus, had to acknowledge a concrete success: the emperor had defended Italy itself.

Politically, this mattered. The capture of Valerian in the east had created a vacuum at the top of imperial authority. Rumors and incomplete information meant that for a time, many did not know whether Gallienus ruled alone, whether his father might somehow return, or whether rival claimants would emerge. A major defeat in Italy could have triggered immediate rebellions. A major victory, by contrast, bolstered Gallienus’ claim to be not merely an accident of succession but a capable war leader.

Coins struck in the years around 259–260 begin to stress themes of security and victory. Legends proclaim “VICTORIA GERMANICA” (Victory over the Germans) and depict the emperor in martial pose, trampling captives or receiving the submission of barbarians. While ancient numismatic evidence must be interpreted carefully, such imagery often reflects recent campaigns. The battle of mediolanum almost certainly fed into this propaganda: concrete triumphs like this provided the raw material from which abstract “victories” on coins were minted.

Within Italy, Gallienus could now move to strengthen defenses more systematically. The shock of the invasion and its repulse highlighted vulnerabilities: under-garrisoned Alpine passes, slow communication between frontier districts and central authorities, cities whose walls were outdated or incomplete. In response, he and his successors pushed for more robust fortification of key nodes, including Mediolanum itself, which would, in coming decades, evolve into a de facto imperial capital for the western half of the empire.

There were social and economic consequences as well. Landowners who had seen their estates threatened—or partially devastated—demanded relief or at least recognition. Some may have received tax remissions or preferential treatment, binding them more closely to the imperial cause. Others, embittered by losses and skeptical of long-term security, might quietly begin to prioritize local self-defense over broader imperial loyalties. The thin line between grateful subjects and potential separatists, always present in the Third-Century Crisis, remained a concern.

In the border provinces, the message was mixed. On the one hand, the defeat of the Alamanni in Italy demonstrated that Rome could still project force rapidly over long distances. On the other, the very fact that such a penetration had occurred at all reminded provincial elites that the frontier was porous, that imperial attention was stretched, and that no region could count on permanent immunity. These impressions would shape how communities in Gaul, Spain, and the Balkans responded to later crises, including the emergence of breakaway regimes.

Gallienus himself seems to have recognized that isolated victories, however dramatic, could not by themselves resolve the underlying structural weaknesses of the empire. Yet he also knew that in politics, perceptions often outran realities. By combining the tangible success of Mediolanum with symbolic gestures—titles, coinage, public ceremonies—he sought to reweave, however imperfectly, the frayed fabric of Roman confidence.

Gallienus Reconsidered: From Failed Heir to Reluctant Savior

For centuries, Gallienus labored under a poor reputation. Late antique and medieval compilers, drawing on lost hostile sources, portrayed him as effeminate, decadent, or indolent—a man more interested in philosophy and pleasure than in the rough business of empire. The anonymous author of the Historia Augusta, a notoriously unreliable but influential collection of imperial biographies, laced its account of Gallienus with anecdotes designed to belittle him. In such a narrative, victories like the battle of mediolanum were treated as footnotes, overshadowed by a general sense of failure.

Modern scholarship has chipped away at this caricature. Starting in the twentieth century, historians began to reassess third-century emperors on the basis of firmer evidence: inscriptions, coins, legal texts, archaeological finds, and more careful readings of earlier authors such as Zosimus and Aurelius Victor. In this reassessment, Gallienus emerges not as a triumphant reformer—his reign remained beset by crises he could not fully solve—but as an adaptable, often energetic ruler who made significant contributions to the empire’s survival.

The battle of mediolanum occupies a key place in this reevaluation. It demonstrates that Gallienus could do more than react passively to events; he could anticipate enemy movements, restructure forces to meet new threats, and lead effectively in the field. His emphasis on cavalry, which played such a decisive role there, aligns with wider shifts known from later sources: the emergence of mobile field armies and the increasing prominence of elite mounted units stationed near key cities like Mediolanum.

Furthermore, Gallienus’ decision to rely less on senators for high military commands and more on professional officers drawn from the equestrian order seems, in retrospect, pragmatic. The old senatorial elite, deeply tied to Italy and traditional political culture, had not always responded flexibly to the new, fast-moving threats of the third century. By appointing more technically competent, battlefield-tested commanders, Gallienus improved the empire’s chances in engagements like Mediolanum, even at the cost of senatorial goodwill.

None of this is to romanticize his reign. During and after the period of the battle of mediolanum, Rome still lost ground: cities sacked in the east by Shapur, breakaway polities emerging in Gaul, inflation eroding the economy. Gallienus died violently in 268, assassinated during a siege of yet another usurper. The reforms he put in place would be taken up, expanded, and sometimes overshadowed by later emperors like Aurelian and Diocletian, whose successful reconquests and sweeping changes left deeper imprints on memory.

But if we imagine the empire without Gallienus’ efforts—without his campaigns on the Rhine and in the Balkans, without his quick march and decisive victory at Mediolanum—the picture darkens. One could plausibly envision a scenario in which Italy suffers a prolonged ravaging, confidence in imperial protection collapses more quickly, and regional secessions become permanent fractures. In that light, Gallienus appears less as a failure and more as a beleaguered caretaker, holding the line just long enough for later stabilizers to do their work.

As historian David Potter observes in his broader study of the third century, understanding men like Gallienus requires looking past the moralizing lens of ancient authors to the structural constraints they faced. By that measure, the emperor who rode to Mediolanum was neither a heroic savior nor a decadent villain but a complex, embattled figure doing what he could in a world unraveling around him.

The Alamanni and the Limits of Roman Power

Roman sources often lumped “Germans” into a vague category of northern barbarians, but the Alamanni, by the time of the battle of mediolanum, were already sophisticated political actors in their own right. Their confederation had grown along the Roman frontier, absorbing smaller groups, negotiating, trading, and fighting with Roman authorities in shifting patterns. They were not ignorant of the empire’s might—or its weaknesses.

Their incursion into Italy, ending so bloodily outside Mediolanum, did not spell the end of their story. Far from it. In the decades and centuries that followed, the Alamanni would continue to play a key role in western imperial history, launching further raids, settling in border regions, and eventually, in the post-Roman world, leaving their imprint on regions of what is now southwestern Germany and Switzerland. The Roman victory in 259 was thus a sharp check, but not a final solution.

This continuity underscores an important truth: Rome, even at its height, rarely annihilated its enemies completely. Its power lay instead in the ability to manage, contain, and co-opt. After the shock of Mediolanum, Roman authorities no doubt sought to stabilize the frontier with a mixture of reprisals and diplomacy. Some Alamannic groups may have quietly received subsidies or trading privileges in return for restraining raids. Others might have been played off against rival confederations.

At the same time, the Alamanni surely learned from their defeat. They had tested the path into Italy and discovered both its opportunities and its perils. Future incursions would take different forms or exploit different weaknesses—along the upper Danube, perhaps, or in coordination with other groups. The battle of mediolanum, in that sense, became one episode in a long-running strategic contest across the Rhine and Alpine regions.

For Rome, the limits of its power were made starkly clear by the mere fact that the battle took place on Italian soil. Even while celebrating victory, perceptive observers could see that the empire had lost the near-absolute control of the frontier it once claimed. Defensive depth was thinning; the buffer zones of securely Romanized provinces were no longer guaranteed shields. In this environment, an outright “solution” to the Alamannic problem—short of massive, unsustainable conquests across the Rhine—was impossible.

Instead, Roman strategy in the later third and fourth centuries would oscillate between offensive campaigns designed to push hostile groups back and pragmatic accommodations with those who could not be permanently subdued. The Alamanni, like the Goths and Franks, became recurring actors in this drama. Mediolanum, in hindsight, appears as an early hinge-point, demonstrating both that Rome could still win major field battles and that these victories did not restore the old, secure order.

Echoes Through Time: Memory, Sources, and Historiography

Our knowledge of the battle of mediolanum is filtered through fragmentary and often biased sources. No detailed contemporary campaign diary survives; instead, historians must piece together references from later authors, inscriptions, coin legends, and the archaeological record. This process is akin to reconstructing a shattered mosaic: some tiles are missing, others are distorted, but patterns emerge when viewed from the right distance.

One key literary witness is Aurelius Victor, a fourth-century historian whose brief imperial biographies (De Caesaribus) mention Gallienus’ struggle against Germanic invaders and the defense of Italy. Another is the historian Zosimus, writing in the early sixth century, who, though separated from events by centuries, drew on earlier, now-lost sources and preserves valuable details about third-century military crises. The notoriously problematic Historia Augusta also includes an account of Gallienus’ reign, though its fanciful elements require constant skepticism.

Modern scholars cross-reference these texts with logistical realities, known frontier deployments, and patterns inferred from coin finds. For example, an increased concentration of coin hoards in northern Italy around the late 250s and early 260s has been interpreted by some as reflecting the disruption caused by the Alamannic invasion and its aftermath. Inscriptions honoring local commanders or civic elites who helped defend cities like Mediolanum add further texture.

Historiographically, interest in the battle has surged alongside broader studies of the Third-Century Crisis. As researchers like Andreas Alföldi and, more recently, Michael Kulikowski and David Potter have argued, understanding this period requires moving beyond the simplistic notion of a linear “decline and fall.” Instead, they emphasize cycles of crisis and recovery, institutional adaptation, and regional variation. The battle outside Mediolanum, once seen only as a footnote to Gallienus’ troubled reign, now appears as a key datapoint in the empire’s learning curve under stress.

Academic tools like the Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire and digital corpora of inscriptions have allowed historians to situate individual actors—officers, governors, local benefactors—in the network of relationships that underpinned imperial resilience. Meanwhile, military historians, drawing on comparative studies of ancient warfare, have highlighted Mediolanum’s significance as an early showcase of the more mobile, cavalry-heavy operational art that would dominate the late empire.

Of course, much remains uncertain. Debates continue over the battle’s exact date, the size of the forces involved, and whether Gallienus fought one or multiple large engagements against Alamannic forces in Italy over a span of months or years. But such debates are part of what makes the study of this episode so compelling. The battle of mediolanum is not a static, settled “fact” but a living inquiry, its contours sharpened each time a scholar revisits the evidence or a new find emerges from an excavation in northern Italy.

Legacy of the Battle of Mediolanum in Military Thought

Although ancient generals did not write “after-action reports” in the modern sense, patterns of practice show that the lessons of major engagements like Mediolanum did not simply vanish. Officers who survived, soldiers who reenlisted, and emperors who read reports or heard accounts from trusted lieutenants carried those experiences into future campaigns. Over time, certain themes crystallized, influencing how the late Roman army organized and fought.

One such theme was the centrality of mobile reserves. The battle of mediolanum highlighted the value of having a powerful, centrally controlled cavalry force that could move quickly to threatened sectors and deliver decisive blows at critical moments. This principle would be formalized in the later third and fourth centuries with the development of the comitatenses, mobile field armies distinct from the border limitanei. Mediolanum, itself later a hub for such forces, foreshadowed this spatial and structural shift in Roman defense.

Another lesson lay in the integration of local and imperial resources. The defense of Mediolanum required cooperation between the imperial field army and the city’s own capacities: its granaries, artisans, civic authorities, and, to some extent, its militia. Later emperors like Aurelian and Diocletian would pursue policies that more tightly bound cities into imperial logistical systems, while also fortifying urban centers across the empire. The notion that interior cities might need to function as temporary military capitals or redoubts was reinforced by episodes like Mediolanum.

In terms of doctrinal thinking, the battle contributed, however indirectly, to a growing awareness that Rome’s enemies were changing. No longer could the empire rely on static frontier lines and slow-moving counterattacks. Instead, it faced fluid confederations capable of deep penetrations and coordinated raids. The response, as Mediolanum demonstrated, was not to abandon heavy infantry—still the backbone of the army—but to pair it with rapid-strike cavalry and flexible command structures capable of seizing fleeting opportunities on the field.

Later military writers such as Vegetius, composing in the late fourth century, would look back on earlier periods of Roman success and exhort contemporaries to emulate them. While he does not mention Mediolanum by name, the principles he advocates—discipline, proper training of cavalry, readiness to meet sudden incursions—resonate with what we can infer about Gallienus’ conduct there. In a sense, the anonymous tactical wisdom distilled in Vegetius’ treatise owes something to countless battles, including the one fought outside that northern Italian city in 259.

Finally, there is the intangible legacy of morale and myth. For the Roman army and its leaders, memories of past victories served as templates for courage. The story of how an emperor outmaneuvered and crushed a large Alamannic host before the walls of Mediolanum would have been told and retold, gaining embellishments with each iteration. Even if the details blurred, the core message endured: that decisive leadership and tactical innovation could still wrest triumph from a world tilting toward chaos.

Conclusion

In the long arc of Roman history, the year 259 and the battle of mediolanum can seem like a brief flare in a storm-filled sky. Yet when we look closer, that flare illuminates much. It shows an empire battered but not yet broken, a leadership adapting under duress, and enemies both formidable and enduring. On those fields outside Mediolanum, the Alamanni tested the permeability of Italy’s defenses, and Gallienus tested the effectiveness of a more mobile, cavalry-centered response. The result was a hard-won Roman victory that preserved the heartland for a time and demonstrated that the empire could still strike fast and hard when cornered.

But the battle did not reverse the wider currents of the Third-Century Crisis. Economic strains, political fragmentation, and external pressures continued to gnaw at the imperial fabric. Even as Mediolanum’s citizens rejoiced and coin minters stamped images of Germanic captives beneath the emperor’s feet, new threats were already forming on distant horizons. The significance of the battle, therefore, lies less in any illusion of finality and more in what it reveals about resilience in an age of ongoing peril.

Through the lens of this single clash, we see the interplay of geography, politics, human will, and institutional change. We meet Gallienus not as a caricature but as a complex ruler whose choices—good and bad—shaped the empire’s chances of survival. We glimpse the Alamanni as more than faceless invaders, recognizing them as persistent neighbors in a shifting frontier world. And we recognize in the people of Mediolanum, trembling behind their walls and then emerging to rebuild, the enduring capacity of communities to endure, adapt, and remember.

Today, walking the streets of modern Milan, the echoes of 259 are almost inaudible beneath the hum of traffic and commerce. Yet under the pavement, in scattered shards of pottery and buried foundations, the traces of that age remain. The battle of mediolanum reminds us that what seems solid—empires, borders, even the sanctity of a homeland—can be frighteningly fragile. It also reminds us that, in moments of acute danger, leadership, preparation, and courage can still tip the balance, if only for a while, in favor of continuity over collapse.

FAQs

- What was the Battle of Mediolanum?

The Battle of Mediolanum was a major clash in 259 CE between a Roman field army led by Emperor Gallienus and an invading Alamannic force that had penetrated northern Italy. Fought near the city of Mediolanum (modern Milan), it ended in a decisive Roman victory that drove the Alamanni out of Italy and temporarily secured the empire’s core provinces. - Why was the battle of mediolanum so important for the Roman Empire?

Its importance lay in geography and timing. Italy had not faced a large-scale barbarian invasion in generations, and the Third-Century Crisis had already undermined confidence in imperial authority. By defeating the Alamanni near Mediolanum, Gallienus proved that Rome could still defend its heartland, shored up his own legitimacy, and bought time for later reforms and reconquests. - Who were the Alamanni, and why did they invade Italy?

The Alamanni were a Germanic confederation inhabiting regions along the upper Rhine. Motivated by a mix of internal pressures, opportunities created by Roman weakness, and the lure of Italy’s wealth, they exploited frontier vulnerabilities to raid deeply into Roman territory, culminating in their advance into the Po Valley and toward Mediolanum. - How did Gallienus win the battle?

Gallienus assembled a mixed force of legionary infantry, auxiliaries, and, crucially, strong cavalry units concentrated around Mediolanum. During the battle, he used his infantry to hold the Alamannic main body, then unleashed his massed cavalry against the enemy flanks at a critical moment. This well-timed cavalry assault shattered the Alamannic formation and turned the engagement into a rout. - What were the longer-term consequences of the battle?

In the short term, the battle of mediolanum secured northern Italy and boosted Gallienus’ standing. In the longer term, it highlighted both the effectiveness of mobile cavalry reserves and the vulnerability of the empire’s interior, influencing later military reforms and urban fortification policies. However, it did not end the Third-Century Crisis, nor did it eliminate the Alamanni as a recurring threat. - How do historians know about the battle?

Historians rely on a combination of later literary sources, such as Aurelius Victor and Zosimus, numismatic evidence (coins celebrating victories over Germans), inscriptions, and archaeological data from northern Italy. While details remain debated, the convergence of these sources supports the basic outline of a major Roman victory over the Alamanni near Mediolanum around 259 CE.