Table of Contents

- The Twilight of the Holy Roman Empire: Europe on the Cusp of Change

- Napoleon’s Grand Design: Vision of a New European Order

- The Treaty of the Confederation of the Rhine: A Political Earthquake

- The Key Players: German Princes, France, and the Emperor

- July 12, 1806: Signing the Birth of a Confederation

- The Dissolution of the Old Empire: From Tradition to Transformation

- Structure and Governance: The Anatomy of the Confederation

- Military Obligations and French Hegemony: Power under Napoleon’s Shadow

- Reactions Across Europe: Allies, Enemies, and the In-Between

- The Confederation’s Impact on German Nationalism and Identity

- The Economic and Social Ripples in the Confederated States

- The Confederation as a Tool of French Strategy in the Napoleonic Wars

- The Symbolism and Legacy of the Confederation in German History

- Collapse and Aftermath: The Confederation’s Demise with Napoleon’s Fall

- Reflections on Sovereignty, Empire, and the Modern State System

- Conclusion: The Confederation’s Enduring Lessons

- FAQs: Understanding the Confederation of the Rhine

- External Resource

- Internal Link

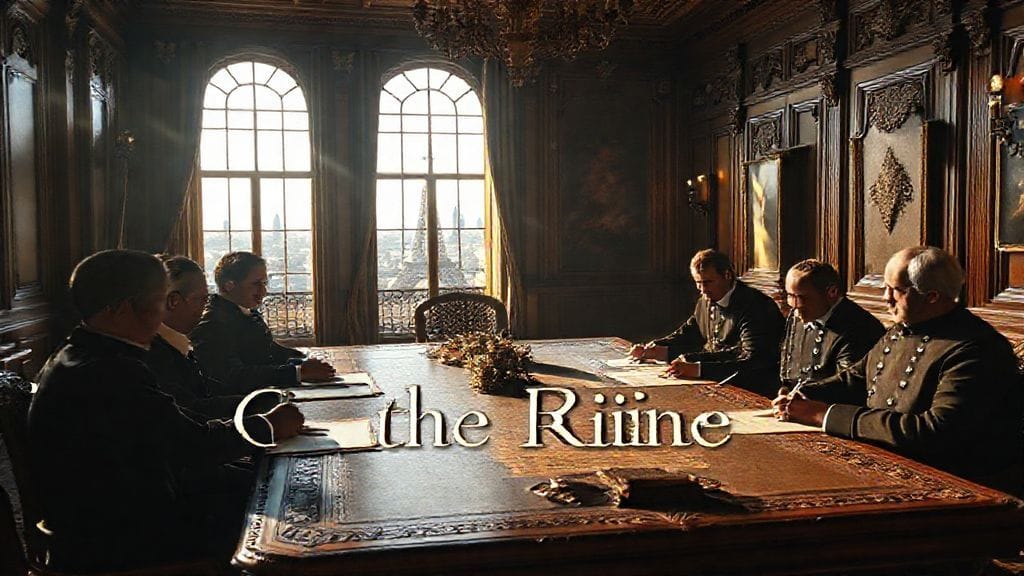

The early morning of July 12, 1806, dawned over Paris quietly, yet beneath the calm, the currents of history churned profoundly. In a stately chamber, leaders of German states gathered to sign a document that would unravel centuries of sacred imperial tradition. The Confederation of the Rhine was born—an alliance forged under the watchful gaze of Napoleon Bonaparte that would mark the definitive end of the Holy Roman Empire and reshape Europe’s political landscape.

The air was thick not just with ceremony, but with tension—a palpable sense of irreversible change. For the ruling families of German principalities, many centuries-old, it was a moment both hopeful and unnerving. They were to cast aside centuries of imperial allegiance and step into a new order, one that promised protection and prestige but under the strict hegemony of the French Emperor. The signing was not merely a treaty; it was the birth of a new era.

But to truly grasp the magnitude of July 12, 1806, one must journey into the chaotic final decades of the old empire, the rise of Napoleon’s unparalleled ambition, and the complex web of diplomacy and warfare that led to this moment. The Confederation of the Rhine was not just a political agreement—it was a dismantling of an ancient world and a prologue to modern nationalism. It was also a definitive assertion of French power, a stepping stone to Napoleon’s dreams of dominion over Europe.

The Twilight of the Holy Roman Empire: Europe on the Cusp of Change

The Holy Roman Empire—an assemblage of hundreds of largely autonomous kingdoms, duchies, and free cities—had long been a patchwork relic of medieval Christendom. By the early 19th century, this empire was a shadow of its past grandeur, wracked by inefficiency and internal discord. The once-great imperial title wielded by the Habsburgs had become largely symbolic, a hollow authority in the eyes of many of its constituent states.

Europe in 1806 was a continent pierced by the fissures of revolutionary change. The French Revolution, with its radical reordering of society and government, had shaken kings and nobles alike. Into this breach stepped Napoleon Bonaparte, a man shaped by revolution but driven by imperial ambition. His ascension as Emperor of the French in 1804 signaled not only the creation of a powerful new monarchy but also a direct challenge to the old European powers.

The German lands, fragmented and often at odds with each other, were a prize for Napoleon’s strategy. The Holy Roman Empire was an unwieldy and outdated institution that neither served the interests of its many rulers nor offered effective governance or defense. Some German princes saw in Napoleon’s offers a chance to strengthen their position, while others were deeply wary of his growing dominion.

Napoleon’s Grand Design: Vision of a New European Order

Napoleon understood that the key to controlling Central Europe was to wrest power away from the Habsburg Emperor in Vienna while binding the German states into a political union loyal to France. His vision was audacious: dismantle the Holy Roman Empire, create a new and streamlined German confederation that would serve as a buffer and ally to France’s western frontier, and assert French dominance over the continent.

To Napoleon, the Confederation of the Rhine was a masterstroke of diplomacy and realpolitik. By offering German princes greater autonomy within a French-led alliance and protection from both Austria and Prussia, he secured their allegiance. In return, these German states renounced their ties to the Holy Roman Emperor and became client states of France.

This reconfiguration threatened not only Habsburg interests but also the fragile balance of power in Europe. The Confederation was a crucial component of Napoleon’s efforts to isolate Britain, contain Russia, and consolidate his sphere of influence.

The Treaty of the Confederation of the Rhine: A Political Earthquake

On July 12, 1806, the treaty establishing the Confederation of the Rhine was signed in Paris by representatives of sixteen German states. Alongside these members, a handful of other principalities would soon join, increasing its strength to around thirty states.

The treaty was not merely a document of alliance; it was the void that dissolved the Holy Roman Empire. In fact, just weeks after the treaty’s signing, the last Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II, abdicated the throne that had existed for over a millennium.

What made the treaty so revolutionary was not only its explicit renunciation of imperial authority but also the detailed provisions for a mutual defense pact under French command. The confederation states swore allegiance to Napoleon, promising military support in exchange for sovereignty within their territories.

The Key Players: German Princes, France, and the Emperor

Key figures shaped the Confederation’s formation. Among the German princes, some were enthusiastic collaborators, eager to increase their power and status under Napoleon’s patronage. The King of Bavaria and the Grand Duke of Würzburg, for example, received elevated titles and expanded territories.

Napoleon himself, at the center of this seismic shift, was both architect and guarantor of this new order. His diplomats skillfully negotiated terms that bind the German states tightly to French interests.

On the opposite end was Emperor Francis II, who faced political isolation and military defeat. His abdication on August 6, 1806, was both an end and a symbol—the official death of the Holy Roman Empire and the start of a new epoch in European geopolitics.

July 12, 1806: Signing the Birth of a Confederation

The ceremony in Paris was grand but fraught with tension. The grand hall echoed with speeches promising mutual defense and cooperation, but beneath the formal words lay apprehensions. Each state sought to protect its heritage and autonomy even as it acquiesced to French supremacy.

Historical accounts reveal vivid scenes: princes adorned in resplendent uniforms, secret whispered anxieties, and the stoic presence of Napoleon, whose gaze signaled that these were not mere suggestions, but decrees of a new order.

The Dissolution of the Old Empire: From Tradition to Transformation

The aftermath was swift. Within weeks, the Holy Roman Empire was formally dissolved. The centuries-old structure that had defined Central Europe vanished, replaced by the new Confederation.

This was a dramatically symbolic victory for Napoleon: a traditional Christian empire—rooted in the ideals of empire and church—was replaced by a secular, modern confederation built on strategic interests and military allegiance.

However, this transformation carried profound uncertainties. German national identity was fractured, caught between loyalty to ancient imperial structures and the new allegiance to France.

Structure and Governance: The Anatomy of the Confederation

The Confederation of the Rhine was not a nation-state but a league of sovereign entities. It established a Federal Assembly, although real power rested firmly with Napoleon and his appointed representatives.

States retained internal autonomy but ceded control over foreign policy and military matters. The Confederation was to serve as a military alliance and a French client system, with member states obligated to contribute troops and resources.

Military Obligations and French Hegemony: Power under Napoleon’s Shadow

One of the core aspects of the Confederation was its military dimension. Member states had to provide soldiers for Napoleon’s campaigns. This meant that the Confederation’s armies fought in the Napoleonic Wars, often against their historical German neighbors.

The conscription drained resources and sent thousands to battlefields, shaping the trajectories of towns and families across the confederation. Yet, it also underscored the limits of sovereignty under Napoleon’s dominance.

Reactions Across Europe: Allies, Enemies, and the In-Between

Reactions were mixed. Britain and Russia viewed the Confederation as an aggressive expansion of French power and a threat to the European balance of power.

Austria, the former imperial power in Germany, was deeply embittered, seeing its influence shrink dramatically. Meanwhile, some German rulers welcomed the end of imperial stagnation and chance for modernization.

The Confederation widened the rift in Europe, fueling further coalitions against France and setting the stage for continued warfare.

The Confederation’s Impact on German Nationalism and Identity

Though born as a French satellite, the Confederation paradoxically stirred early expressions of German nationalism.

Intellectuals and common citizens began imagining a unified German nation beyond fragmented princes and foreign domination. Poets like Ernst Moritz Arndt and Johann Gottlieb Fichte voiced calls for unity and freedom.

Thus, the Confederation became an involuntary catalyst in the long journey toward German unification.

The Economic and Social Ripples in the Confederated States

Politically beholden to France, the member states nonetheless pursued internal reforms inspired by Enlightenment ideals. Many rulers modernized administration, abolished feudal privileges, and promoted legal reforms.

Yet, the economic burden of war and conscription strained social fabrics. Towns lost young men to battles, agriculture and commerce faced disruptions.

Nevertheless, new connectivity and centralized administration laid early groundwork for future economic integration.

The Confederation as a Tool of French Strategy in the Napoleonic Wars

From a military perspective, the Confederation was indispensable to Napoleon’s campaigns.

It provided a buffer zone protecting France’s eastern borders and a reservoir of soldiers. Its armies fought decisively in battles such as Austerlitz (1805) and Jena-Auerstedt (1806), pivotal victories confirming Napoleonic dominance.

But the heavy reliance on client states also revealed vulnerabilities—when Napoleon’s fortunes waned, so too did the Confederation’s cohesion.

The Symbolism and Legacy of the Confederation in German History

Historically, the Confederation of the Rhine is remembered as a turning point—a symbolic rupture from the medieval past and a step toward modern statehood.

While a French puppet on one hand, it paradoxically set in motion forces of German political and cultural identity that endured long after Napoleon’s fall.

Collapse and Aftermath: The Confederation’s Demise with Napoleon’s Fall

By 1813, the Confederation unraveled amid Napoleon’s military defeats. Member states defected, joined coalitions, or reconfigured their allegiances.

At the Congress of Vienna (1815), a German Confederation under Austrian influence replaced the Napoleonic institution, restoring fragmented sovereignty but acknowledging modern realities.

Reflections on Sovereignty, Empire, and the Modern State System

The Confederation represents a pivotal case in sovereignty’s evolution—highlighting tensions between imperial tradition, dynastic rule, and emerging ideals of statehood and nationalism.

It illustrates how power, diplomacy, and war reshape borders and identities in ways still echoing in contemporary Europe.

Conclusion

The Confederation of the Rhine stands as a powerful testament to the relentless forces of change in history. It was a creation born from the collapse of the old and the ambitions of the new—a stage where centuries-old empires dissolved and modern political identities began to crystallize.

Though ultimately a tool of Napoleonic dominance, the Confederation revealed the fragility of old orders and the possibilities unlocked by new alliances and ideas. It accelerated the vanishing of feudal Europe, sowed seeds of German nationalism, and paved the way for the age of nation-states.

In the living rooms and council chambers of 1806, amid the pomp of treaty signing, lay the echoes of revolutions yet to come—proof that history is never static, and no empire, however mighty, is permanent.

FAQs

1. What was the Confederation of the Rhine?

It was a coalition of German states established in 1806 under French protection, dissolving the Holy Roman Empire and serving as a French client alliance.

2. Why did the Confederation replace the Holy Roman Empire?

Napoleon aimed to weaken the Habsburgs and reorganize Germany into a streamlined alliance loyal to France, rendering the outdated empire obsolete.

3. How did the Confederation affect German nationalism?

Despite its origins as a French puppet, the Confederation stimulated German unification ideas by highlighting the need for a stronger, more unified identity.

4. Which states were members of the Confederation?

Initially sixteen German states joined, including Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, and others, eventually expanding to about thirty members.

5. What obligations did member states have?

They pledged military support to Napoleon and agreed to French-dominated foreign policy while maintaining internal control.

6. How long did the Confederation last?

It existed from 1806 until Napoleon’s defeat in 1813, after which it collapsed and was replaced by the German Confederation at Vienna.

7. What was the impact on the Holy Roman Emperor?

Emperor Francis II abdicated, ending the Holy Roman Empire’s thousand-year legacy.

8. How is the Confederation remembered today?

As a pivotal moment of transition from medieval empire to modern nation-states, and an early catalyst of German nationalism.