Table of Contents

- A Gathering in Turbulent Times: The First Council of Orange

- The Twilight of the Western Roman Empire: Gaul on the Brink

- Seeds of Theological Controversy: Pelagianism and Augustine’s Legacy

- Who Were the Fathers of Orange? Key Figures of the Assembly

- The Call to Council: Why Orange, Why Now?

- Opening Sessions: The Atmosphere and Initial Declarations

- The Pelagian Crisis Unveiled: Doctrinal Battles on Grace and Free Will

- Affirming Augustine: The Council’s Theological Compass

- Doctrinal Canons: The 28 Decrees That Shaped Western Christianity

- The Aftermath: Immediate Impact on Gaul and the Wider Church

- Echoes Through Time: How Orange Influenced Medieval Theology

- The Council’s Role in the Christianization of Europe

- The Power Struggles Beneath the Surface: Politics and Religion in 5th Century Gaul

- Orange and the Formation of Western Orthodoxy

- Cultural and Social Reflections of the Council's Decisions

- Personalities Behind the Doctrine: Stories of Bishops and Theologians

- Controversy Over Predestination: Orange vs. Later Theological Disputes

- The Council’s Legacy in Modern Christian Thought

- Archaeological Discoveries and the Memory of Orange

- Reassessing Orange: Contemporary Scholarship and Debates

- Conclusion: The Lasting Flame of a 5th Century Assembly

- FAQs about the First Council of Orange

- External Resource

- Internal Link

1. A Gathering in Turbulent Times: The First Council of Orange

In the summer of 441 CE, the city of Orange in the Roman province of Gaul transformed from a quiet provincial hub into a vital theater of theological confrontation. As bishops and clergy assembled in its basilicas, the air was charged with tension — the kind born not merely of political uncertainty, but of profound religious conflict that threatened the very foundation of Christian belief in the Western world. The first Council of Orange was convened in an era defined by disarray: the empire was unraveling, barbarian pressures mounted from the north and east, and within the Church, sharp disputes over grace, free will, and sin had fomented a fissure. This council, though modest in scale, would carve out a lasting framework that would reverberate through centuries of Christian doctrine.

Behind closed doors, the minds that shaped Christian orthodoxy debated questions that tore at the heart of salvation and human agency. Would mankind’s will, tainted by original sin, be able to cooperate with divine grace, or was grace an irresistible force overridden by human intent? Could individuals be righteous through their own merits or solely through God’s gift? These questions were more than academic; they defined how humanity viewed itself in relation to God’s mercy.

Yet, Orange was not simply a theological battleground. It was also a moment of hope, a council that sought unity in a fragmented world. As the bishops departed, their decrees aimed to offer clarity and peace to Christians across Gaul and beyond.

2. The Twilight of the Western Roman Empire: Gaul on the Brink

By 441, the Western Roman Empire was in decline, fracturing under the weight of internal instability and external pressures. Gaul, once a jewel in the imperial crown, had become a patchwork of Roman and barbarian territories. The Visigoths, Franks, and Burgundians jostled for influence, while Roman imperial administration weakened. Against this backdrop, the Church was one of the few stable institutions that continued to bind communities.

The Church had become the spiritual and moral authority in a crumbling state. Bishops were not just spiritual leaders; they were civic leaders, arbitrators of law and public order, and essential mediators between Roman traditions and emerging barbarian kingdoms. The theological clarity they preserved was thus entangled with social cohesion and political power.

Within this context, the Council of Orange carried a heavy burden. It was more than a religious meeting — it was a plea for unity in a time when civilization seemed poised on the edge of collapse.

3. Seeds of Theological Controversy: Pelagianism and Augustine’s Legacy

To understand the significance of the Council of Orange, one must first grasp the theological controversies it addressed. In the 4th and early 5th centuries, Pelagianism had erupted as a heresy that challenged key Christian teachings about sin and grace. Pelagius, a British monk, argued that human beings had the innate capacity to choose good without the necessity of divine grace — effectively denying original sin’s damaging effects on human nature.

This posed a stark challenge to Augustine of Hippo’s teachings, which emphasized humanity’s profound dependence on God’s grace for salvation. Augustine argued that original sin left man spiritually incapacitated, unable to choose good unless moved by grace.

While the Church condemned Pelagianism, the debate remained heated. The Council of Orange sought not just to refute Pelagian claims but to articulate a more precise theology of grace and free will that would avoid extremes.

4. Who Were the Fathers of Orange? Key Figures of the Assembly

The Council was presided over by Bishop Hilary of Arles, one of the most influential ecclesiastical figures in Gaul. Pope Leo I’s influence was also palpable, as his theological leadership had significantly shaped Western Christendom. Bishop Viator of Orange, whose see hosted the council, provided local support.

Though records from the council are sparse, the bishops represented a wide spectrum of Gaul’s Church hierarchy. They embodied a generation seeking doctrinal clarity amidst religious confusion and political turmoil. Their theological acumen, paired with pastoral concern, lent the council's decrees weight and authority.

5. The Call to Council: Why Orange, Why Now?

Why 441, and why Orange? The urgency stemmed from escalating controversy over doctrines of grace and free will disrupting the unity of the Gallic Church. Without firm theological boundaries, divisions risked fracturing Christianity’s moral authority at a fragile historical moment.

Orange, situated strategically in southern Gaul with convenient accessibility and a known ecclesiastical seat, was a natural choice. The city had a long tradition of Christian practice and stood relatively secure amid the turmoil.

The council’s summoning was thus both timely and symbolic — a gathering to confront the storm at the heart of Christian belief.

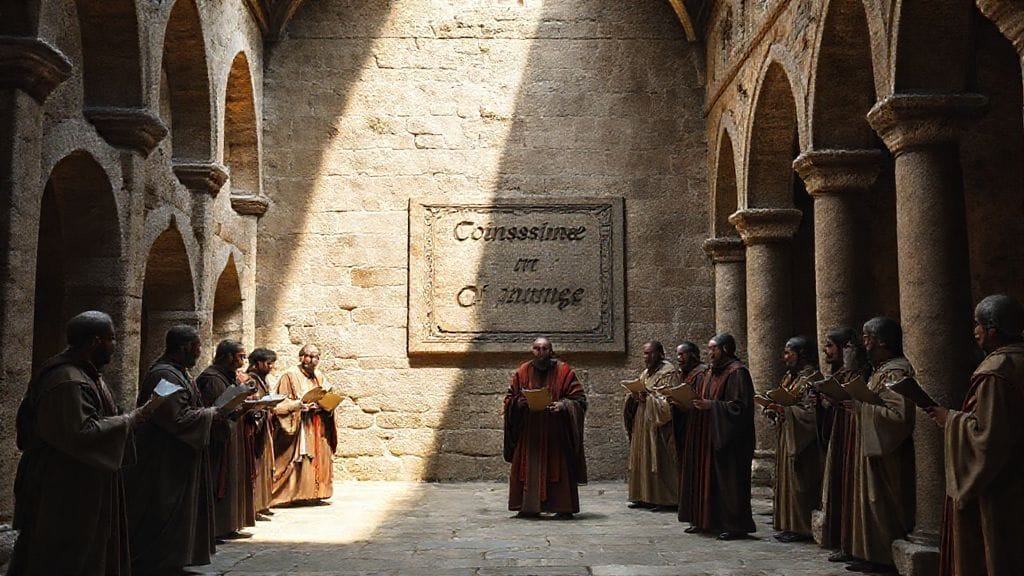

6. Opening Sessions: The Atmosphere and Initial Declarations

Imagine the large basilica filled with robed bishops, clergy, and observers — incense smoke curling, voices hushed but urgent. The opening prayers invoked divine guidance to settle disputes in charity and truth. Bishops read from scriptures, reminding all of the stakes: the salvation of souls.

From the outset, the atmosphere was one of earnest solemnity tinged with the undercurrents of rivalry and urgency. The room reflected a microcosm of Gaul: a disparate yet hopeful assembly unified by faith and a shared desire for doctrinal peace.

7. The Pelagian Crisis Unveiled: Doctrinal Battles on Grace and Free Will

The core of the council’s work dealt with Pelagianism head-on. Pelagian views stripped grace of necessity and original sin of universality. The council refuted these claims by affirming that, although free will existed, it was wounded by sin and insufficient without God’s grace.

This stance walked a delicate line: asserting grace’s primacy without negating human responsibility. "Grace is not given because of merits," the council decreed, "but free will, enlightened and aided by grace, cooperates."

It was a nuanced view, laying groundwork that would influence doctrines of cooperation (synergism) in salvation.

8. Affirming Augustine: The Council’s Theological Compass

The council’s canons repeatedly invoked the authority of Augustine. His articulation of original sin’s effects and the necessity of grace had been debated but was now explicitly endorsed. Orange declared that "the grace of Jesus Christ is necessary for man to will and to do good."

This was an important moment, as it marked the first conciliar affirmation of Augustinian theology in the Western Church. It helped consolidate doctrinal cohesion amid a fractured religious landscape.

9. Doctrinal Canons: The 28 Decrees That Shaped Western Christianity

The Council produced 28 canons or formal decrees. These distilled its theological positions on sin, grace, and free will. They explicitly condemned Pelagianism while rejecting fatalism — the idea that human will is powerless.

Key canons emphasized:

- Original sin’s inheritance by all humanity

- The necessity of prevenient grace for faith and good works

- The genuine freedom and responsibility of human will in cooperation with grace

- The rejection of the notion that grace destroys free will

These decrees would become foundational texts for Western theological reflection.

10. The Aftermath: Immediate Impact on Gaul and the Wider Church

The council’s decisions reverberated through Gaul’s ecclesiastical hierarchy. Bishops were tasked with teaching and enforcing its doctrines, stabilizing the Church’s unity.

Though initially confined regionally, the Council of Orange’s decrees influenced later synods and popes, especially in grappling with Pelagianism’s persistence and related heresies.

11. Echoes Through Time: How Orange Influenced Medieval Theology

Medieval thinkers repeatedly cited Orange in debates on grace and free will. The Augustinian framework that Orange cemented became a cornerstone for theologians like Thomas Aquinas and later reformers.

The council’s nuanced approach helped the Church avoid extremes — neither Pelagian overconfidence in human ability nor catastrophic predestination. This doctrinal balance profoundly shaped Western Christianity’s moral and spiritual outlook.

12. The Council’s Role in the Christianization of Europe

By clarifying salvation’s mechanics, the council indirectly aided missionary efforts in barbarian kingdoms. The reinforced orthodoxy helped integrate diverse peoples into the Christian fold with shared faith and practice.

Orange thus contributed to the cultural transformation of Europe, weaving Christianity more deeply into the continent’s identity.

13. The Power Struggles Beneath the Surface: Politics and Religion in 5th Century Gaul

While ostensibly theological, the council also navigated church politics and relations with secular powers. Bishops exercised growing influence amid waning imperial authority.

The council’s affirmation of grace also reinforced Church authority — reminding rulers and the faithful alike of divine sovereignty over all earthly matters.

14. Orange and the Formation of Western Orthodoxy

The council played a pivotal role in defining orthodoxy distinct from Eastern and African theological traditions. It underscored the Western Church’s growing independence and theological identity.

15. Cultural and Social Reflections of the Council's Decisions

The council’s decisions mirrored broader social shifts: an emphasis on personal accountability coupled with trust in divine mercy resonated with a populace enduring war, loss, and uncertainty.

Church teachings shaped moral conduct, charity, and penitential practices in Gaul’s towns and countryside.

16. Personalities Behind the Doctrine: Stories of Bishops and Theologians

Though often anonymous in history, figures like Hilary of Arles exemplify the pastoral and intellectual leadership of the time — balancing faithfulness to Rome, local needs, and theological rigor.

17. Controversy Over Predestination: Orange vs. Later Theological Disputes

The council avoided harsh predestinarian language that would later polarize Christianity during the Reformation. It affirmed grace’s primacy while preserving human free will — a delicate middle path.

18. The Council’s Legacy in Modern Christian Thought

Today, Orange remains a touchstone in Christian theology, cited in ecumenical dialogues and discussions of grace and human freedom.

Its balanced vision continues to inspire those seeking unity amid doctrinal diversity.

19. Archaeological Discoveries and the Memory of Orange

Remnants of Orange’s basilicas and inscriptions offer tangible links to the council. These archaeological finds enrich our understanding of 5th-century ecclesiastical life.

20. Reassessing Orange: Contemporary Scholarship and Debates

Modern historians debate the council’s exact impact and context, reflecting on its nuanced legacy and role within broader late antique Christianity.

21. Conclusion: The Lasting Flame of a 5th Century Assembly

The First Council of Orange stands as a beacon of theological clarity during a time of collapse and confusion. Its careful articulation of grace and free will forged a path between extremes — shaping Western Christianity’s heart for centuries.

More than a historical footnote, Orange reminds us that faith and reason, grace and freedom, are eternal tensions woven into the human quest for salvation. In a world still wrestling with these questions, the council’s voice remains stirring and relevant.

FAQs about the First Council of Orange

Q1: What was the main purpose of the First Council of Orange?

The council aimed to address the Pelagian controversy by clearly defining the Church’s teaching on original sin, grace, and human free will.

Q2: Why was Pelagianism such a threat to the Church?

Pelagianism denied original sin’s effect and minimized the necessity of grace, undermining core doctrines about salvation and corrupting Christian moral teaching.

Q3: How did the Council of Orange influence later Christian theology?

It affirmed Augustine’s views on grace, forming a foundation for medieval theology and influencing debates through the Reformation and beyond.

Q4: Who were the key figures involved in the council?

Bishop Hilary of Arles led the council, with participation from regional bishops and influence from Pope Leo I’s theological leadership.

Q5: Did the council resolve all controversies about grace and free will?

Not entirely; it provided clarity and balance, but debates continued, influencing later theological developments and divisions.

Q6: How is the Council of Orange remembered today?

It is respected for its doctrinal clarity and balanced approach, frequently cited in theological scholarship and ecumenical discussions.

Q7: What were the social impacts of the council's decisions?

The council strengthened Church unity and moral teaching, which supported social cohesion amid the political instability of late Roman Gaul.

Q8: Are there any archaeological evidences of the council?

Yes, remnants of the basilicas and inscriptions in Orange provide historical context and material evidence of the council.