Table of Contents

- A Winter Night in Karakorum: The Last Hours of Ögedei Khan

- From Temujin’s Son to Great Khan: The Path to Power

- A World on Fire: The Mongol Empire at Its Zenith

- Wine, Weariness, and Warnings: The Decline of Ögedei’s Health

- December 11, 1241: The Silent Collapse of an Empire’s Center

- Rumors, Causes, and Controversies Around Ögedei’s Death

- Karakorum in Mourning: Rituals, Oracles, and Political Theater

- The Halt of the Mongol Thunder in Europe

- Regency and Intrigue: Töregene Khatun Takes the Stage

- Brothers, Cousins, and Enemies: The Succession Crisis Unfolds

- The Long Road to Güyük: Kurultai, Delay, and Division

- Shifting Frontiers: How the Death Reshaped Eurasian Politics

- Everyday Lives in Turmoil: Traders, Peasants, and Captives

- Chroniclers, Myths, and Memory: How History Remembered Ögedei

- If the Khan Had Lived: Plausible Paths Not Taken

- Echoes Across Centuries: Why Ögedei’s End Still Matters

- Conclusion

- FAQs

- External Resource

- Internal Link

Article Summary: On a cold December night in 1241, far from the burning cities of Europe and the Middle East, the Mongol world changed forever with the death of Ögedei Khan in Karakorum. This article explores the sweeping rise of the Mongol Empire under Genghis Khan’s son, then narrows in on the human fragility and political stakes surrounding his final days. It shows how the death of ögedei khan not only halted the Mongol advance into Europe, but also shattered the delicate balance among rival princely factions. Through narrative scenes, historical analysis, and voices of medieval chroniclers, we trace how a single man’s passing could redirect the fate of millions across Eurasia. We follow the regency of Töregene Khatun, the bitter struggle to enthrone Güyük, and the gradual fragmentation that began at the very moment of supposed triumph. Along the way, the article reveals how the death of ögedei khan affected traders, peasants, and prisoners of war whose lives were bound to imperial decisions made in a distant steppe capital. It also examines how historians and storytellers, from Persian courtiers to European monks, remembered and sometimes distorted his legacy. Ultimately, the narrative asks what might have happened had Ögedei lived longer, and why the death of ögedei khan remains one of the most consequential turning points in medieval global history.

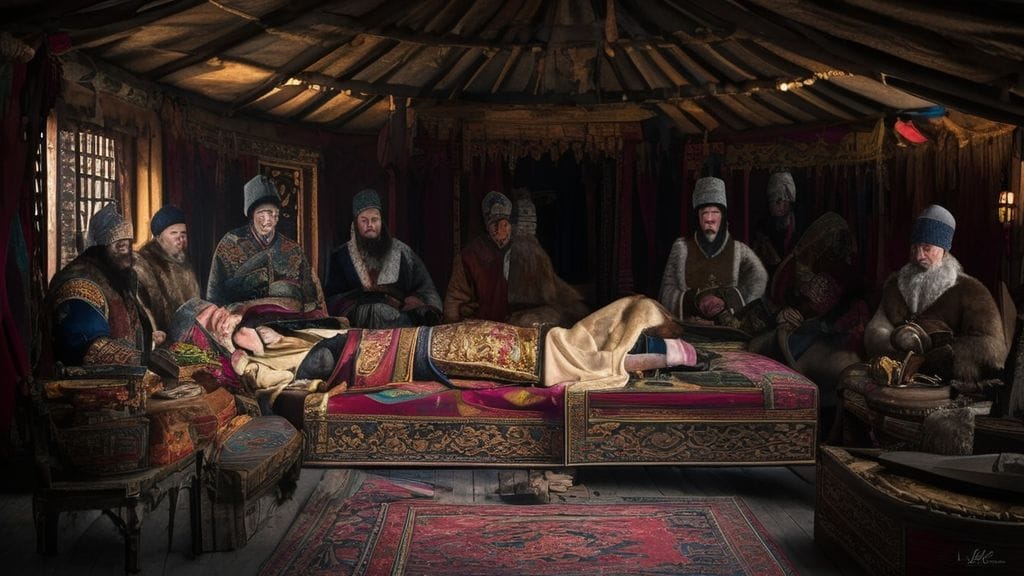

A Winter Night in Karakorum: The Last Hours of Ögedei Khan

The wind that rolled over the steppe on the night of December 11, 1241, carried with it the brittle sharpness of deep winter. In the Mongol capital of Karakorum, campfires burned low, their smoke braided into the night sky as guards paced in heavy boots around the palatial quarters of the Great Khan. From a distance, the city did not look like the center of the largest empire the world had ever seen. It was a raw, growing settlement of wooden palaces, felt gers, workshops, and temples, clinging to the Orkhon River, surrounded by snow-dusted hills and the faint silhouettes of mounted patrols. Yet within its walls lay the beating heart of a realm that stretched from the Sea of Japan to the fringes of the Holy Roman Empire.

Inside his residence, Ögedei Khan, son of Genghis Khan and ruler of this vast dominion, was failing. Those who served close to him had seen the signs long before this final night: the heavy breath, the swelling belly, the eyes that drooped beneath the weight of wine and years of relentless administration and campaigning. But Mongols were taught to face death with a stoic calm, and in the court it was considered dangerous, even treasonous, to speak too openly of the Khan’s fragility. Servants whispered; advisers watched in silence; and the family waited, torn between personal grief and political calculation.

The death of ögedei khan did not come amid the chaos of battle or under the banners of a foreign campaign. It came in a quiet capital, while his generals crushed Europe under iron hooves far to the west. Envoys moved in and out of his presence, bringing news of victories: the fall of Kiev, the devastation of Poland and Hungary, the flight of kings and bishops before Mongol riders. To many in Karakorum it seemed that the empire had reached a peak of unstoppable power. Yet behind the celebrations, a more ominous story was unfolding within the Khan’s own body.

That night, the palace lamps burned against the dark as attendants moved in soft, hurried steps. Some recounted later that the Khan had been in good spirits earlier in the evening, drinking heavily, as he often did, celebrating the successes of his commanders in Eastern Europe. Others claimed that his face had grown ashen, that he gasped for air, that he could not finish his ceremonial duties. What is clear is that at some point, the fragile balance simply broke. Whether it was a failing liver, a failing heart, or a slow accumulation of years of excess, the man at the center of the Mongol world collapsed into stillness.

That stillness spread like a shock wave. The energetic pulse of the court hesitated; conversations dropped to whispers; riders stood ready, knowing they might soon be dispatched with news that would change the world. The death of ögedei khan, when it finally became certain, was not announced with trumpets but with the closed faces of the guards and the gathering of princes and generals in hushed council. Outside, Karakorum itself did not yet know. Fires continued to burn, herds continued to graze at the edges of the city, and traders in shaded stalls counted their coin. But everything around them had already begun to tilt.

It is astonishing, isn’t it, how a single breath—the last exhalation of one aging conqueror—could alter the fate of continents? In the forests of Poland and on the plateau of Hungary, the Mongol advance paused and then turned back. In far-flung courts from Baghdad to Paris, omens were interpreted and rumors began to swirl: had the Mongols finally been stopped by a miracle, or had something far away in the East changed the logic of the war? That night in Karakorum, as the body of the Great Khan lay motionless, the answer was taking shape in the stunned faces of his family and the cold calculations of those who survived him.

From Temujin’s Son to Great Khan: The Path to Power

To understand the magnitude of the death of ögedei khan, one must first see the arc of his life against the backdrop of Mongol ascendance. Ögedei was born into hardship, long before palaces rose at Karakorum. His father, Temujin, was not yet Genghis Khan, not yet the scourge and unifier of the steppe, but a hunted chieftain struggling to rebuild the shattered remnants of his family’s fortunes. The young Ögedei grew up amid hunger and flight, learning to ride, hunt, and survive in a world where alliances shifted as quickly as the winds across the grasslands.

He was not the most brilliant or the most ferocious of Genghis Khan’s sons; Jochi, his elder half-brother, had a reputation for charisma and daring, while Chagatai was famed for his iron will and temper. Ögedei was often described as amiable, generous, and soft-spoken, with a tendency toward indulgence in drink. But he possessed one quality that mattered deeply to his father: reliability. Genghis Khan learned that he could trust Ögedei to carry out orders, to negotiate between feuding relatives, and to bend his will to the discipline of the larger project of empire-building.

As the Mongols burst from the steppe and began to swallow neighboring kingdoms, Ögedei rode with the main army. He was there in the brutal campaigns against the Jin dynasty in northern China, where Mongol troops laid siege to great cities with a ferocity that stunned contemporaries. He witnessed the crossing of mountain ranges, the capture of walled strongholds, and the steady refinement of techniques that would make Mongol warfare unmatched in its era. Through it all, he absorbed both the glory and the grimness of conquest: the burning suburbs, the caravans of captives, the wealth flowing in tribute back to the heartland.

In 1227, when Genghis Khan died during the campaign against the Western Xia, the empire stood at a crossroads. Who would inherit this enormous machinery of war and governance? The selection of Ögedei was not inevitable, but it was deliberate. At a great kurultai, or assembly, the leading members of the imperial family and the nobility gathered, and Genghis’s testament—real or constructed in political retrospect—was invoked on Ögedei’s behalf. His brothers Chagatai and Tolui, each powerful in his own right, gave their support, at least publicly. The choice balanced competing factions, calmed tensions, and projected a sense of continuity.

Thus Ögedei became the second Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, stepping into his father’s shadow but also into a role that demanded something more than battlefield prowess. He had to transform a loose confederation of conquered territories and vassal kings into a functioning imperial system. Temujin had begun that process; Ögedei would, for a time, make it real.

A World on Fire: The Mongol Empire at Its Zenith

When Ögedei assumed the title of Great Khan, the Mongols already controlled an arc of territory that would have seemed fantastical a generation earlier. From the grasslands of Mongolia the empire stretched into northern China, deep into Central Asia, and across the shattered remains of the Khwarazmian Empire. Under Ögedei’s reign, this dominion expanded still further, reaching into Korea, the heartlands of the Jin, the Caucasus, the Rus’ principalities, and eventually into the plains of Eastern Europe.

To see the empire as it stood around 1241 is to glimpse something like a proto–global system. Endless caravans wound along the Silk Roads, now largely pacified by Mongol rule. A merchant could travel from the Yellow River to the Dnieper under the unfurling standard of the Great Khan, paying taxes and tolls but also enjoying unprecedented security on roads that had previously been haunted by bandits and the hazards of war. Religious figures moved almost as freely: Nestorian Christians, Buddhist monks, Muslim scholars, and Daoist holy men all found their way to Karakorum, invited by a court that, while ruthless in war, was remarkably tolerant in matters of belief.

Ögedei took his role as organizer seriously, even if he often took refuge in alcohol from the weight of responsibility. He ordered the construction of Karakorum as a permanent capital, signaling a new phase in Mongol history. No longer would the khans simply be nomadic warlords roaming from camp to camp; now there would be archives, stone inscriptions, artisan quarters, and palaces capable of impressing envoys from the most sophisticated sedentary states. He appointed administrators, many of them drawn from conquered populations, to manage taxation, supplies, and communication across the enormous distances of his realm.

At the same time, the army remained the core instrument of Mongol power. Under the overall direction of the Great Khan, brilliant commanders like Subutai carried out campaigns with a level of coordination and planning that startled their foes. During Ögedei’s reign, this military machine achieved some of its most spectacular feats: the final collapse of the Jin dynasty in 1234, the devastating raids into the Islamic world, and the deep thrusts into Russia and Eastern Europe. Chronicles relate that at Mohi in 1241, on the plains of Hungary, the Mongols annihilated the forces of King Béla IV with a combination of feigned retreats, coordinated multi-column maneuvers, and the brutal efficiency of their archery and siege engines.

It is easy, looking back, to see the Mongol Empire under Ögedei as a monolith of unstoppable power. But inside that monolith were hairline fractures. The different branches of the imperial family—descendants of Jochi, Chagatai, Ögedei, and Tolui—each held rich appanages, commanded their own armies, and nursed their own ambitions. Ögedei, as Great Khan, was the nominal center that held these rivalries in check. His authority could override disputes, redirect campaigns, and decide questions of succession. The strength of the empire depended on the strength, or at least the recognized legitimacy, of the man who held that central position.

And so the death of ögedei khan would not just remove a ruler; it would destabilize the entire structure that had turned disparate tribes into a world-devouring empire.

Wine, Weariness, and Warnings: The Decline of Ögedei’s Health

Behind the façade of triumph, the Great Khan’s body was quietly unraveling. By the late 1230s, those closest to Ögedei had become well aware of his physical decline. His fondness for alcohol was legendary within the court and not always in a complimentary way. Some accounts describe him as rarely seen without a goblet in hand; others recall moments when he was unable to complete ceremonies because he was too drunk to stand. His physicians and advisers were not blind to the danger. According to later sources, at least one of his brothers—likely Chagatai—begged him to moderate his drinking, even having wine rationed, only for the Khan to circumvent these controls with his irresistible authority.

Modern historians, reading through the fragments of Persian chronicles and the so-called “Secret History of the Mongols,” have tried to reconstruct the toll this lifestyle took on his health. Chronic liver disease, heart failure, or perhaps complications of diabetes have all been suggested. But in a world without modern diagnostic tools, what mattered to contemporaries was the visible weakening of their ruler. His once-vigorous presence gave way to a figure increasingly beset by fatigue. He could still issue orders, still entertain envoys and direct campaigns, yet the intervals of rest grew longer, and the intervals of clarity grew shorter.

Warnings came, too, in the form of omens—or at least they were remembered that way later. Horses stumbled during ceremonial rides. A fire supposedly burned too near the palace. An eclipse was interpreted by some shamans as a sign that the balance of the heavens was shifting. The Mongols, though not bound by a single rigid religious system, paid close attention to the patterns of the sky and the whisperings of their spiritual specialists. But Ögedei, proud and perhaps fatalistic, appears to have brushed such concerns aside. His lifestyle did not change.

At the same time, the pressures of ruling the empire bore down on him. Decisions about who would inherit various territories, how to manage the increasingly complex tax systems in conquered lands, and whether to push deeper into Europe or consolidate in the Islamic world all demanded judgment and stamina. The Great Khan was not simply a warlord; he had become, in effect, the head of a sprawling bureaucratic and military machine. It is difficult to imagine that the psychological strain of this role did not compound the physical strain already inflicted by alcohol and age.

Yet, even as those close to him worried, they also relied on his presence to arbitrate their disputes. The princes expected Ögedei to live long enough to guide the succession, to balance the ambitions of different branches of the family. That expectation would prove tragically misplaced.

December 11, 1241: The Silent Collapse of an Empire’s Center

In the chronology of world history, certain dates flicker with disproportionate power. December 11, 1241, is one of them. On that day—or night, as some accounts suggest—the Great Khan of the Mongols died in his capital of Karakorum. The details are maddeningly incomplete, filtered through the inevitable haze of grief, political censorship, and later legend. Nonetheless, historians have tried to assemble the fragments into a coherent narrative of those crucial hours.

By late 1241, news of sweeping victories in Europe had reached the Mongol heartland. Subutai and Batu had smashed Polish and Hungarian armies, ravaging towns and monasteries, sending panicked refugees flooding westward. It is believed that Ögedei, hearing reports of these triumphs, engaged in still more lavish celebrations. Feasts were held in Karakorum, where roasted meats, fermented mare’s milk, and abundant wine flowed in quantities fit for the ruler of half the known world.

One tradition holds that after such a feast, ignoring the pleas of his physicians, Ögedei continued drinking into the night until his body simply gave out. Another suggests he had been frail for weeks, and the feast was only the last in a series of blows to an already failing constitution. What is consistent in the sources is that his death was not violent in the ordinary sense; there were no assassins’ blades, no poisonings admitted to by terrified servants. Instead, the Great Khan seems to have succumbed to a chronic decline, suddenly accelerated, in a climate of indulgence he refused to relinquish.

When the moment came, the inner circle must have reacted with stunned urgency. Rituals had to be observed: shamanic specialists would be called, prayers muttered, incense and offerings prepared. According to Mongol custom, the body of a Great Khan was to be buried in secrecy, its final resting place hidden from all but a select few, often somewhere in the sacred mountain ranges of Mongolia. Whether the rituals began the same night or only after the news was fully confirmed, the palace would have turned swiftly from a place of feasting to one of hushed logistical fury.

Politically, however, the implications were more explosive still. The death of ögedei khan meant that the empire had lost its central arbiter at the very moment it stood poised for still greater expansion. Caravans could be redirected; generals could be recalled; rival branches of the family could press their claims. Yet nothing, at least in the Mongol system, could legitimately move forward on questions of supreme command until a new Great Khan had been chosen at a grand kurultai. In that pause—between the last breath of Ögedei and the next enthronement—lay a window in which everything was uncertain.

Word of the Khan’s death did not, of course, fly instantly across Eurasia. It traveled by horse, relay stations, and trusted envoys. Still, within weeks, perhaps even days, the first orders began to reach distant commanders. Batu and Subutai, deep in Eastern Europe, received messages summoning them back for the succession. The unstoppable advance into the heart of the continent suddenly slowed and then ceased. While Europe’s chroniclers praised the intervention of saints or divine mercy, the truth was starkly political: the Mongol war machine could not simply rampage on without a universally recognized center of authority.

Rumors, Causes, and Controversies Around Ögedei’s Death

What exactly killed the Great Khan? That deceptively simple question has become one of the enduring controversies surrounding the death of ögedei khan. Medieval chroniclers were fascinated by the fall of such a powerful figure, yet their explanations were shaped by their own cultural lenses and political agendas. Some Muslim historians, writing in the Ilkhanate a few generations later, highlighted the moral failings of indulgence, depicting Ögedei’s alcoholism as a cautionary tale about excess and divine judgment. “Wine killed the Khan as surely as any blade,” one might paraphrase from their tone.

Persian historian Juvayni, in his celebrated work History of the World Conqueror, presents Ögedei as generous and humane compared to some of his relatives, but also notes his weaknesses. European chroniclers, hearing rumors in the wake of the sudden Mongol withdrawal from Europe, speculated on plague, divine punishment, or even internal coup. None had direct access to Karakorum; all relied on word of mouth, often traveling along the same trade routes that carried silks and spices.

Modern historians usually settle on complications of chronic alcoholism as the most likely cause: liver failure, stroke, or heart failure. Evidence in the sources that he was warned to cut back on drinking, that wine allowances were restricted, and that he defied such advice repeatedly, all point in that direction. The Mongol elite’s culture of feasting, in which to decline a drink might be taken as an insult or a sign of weakness, did not help. The Great Khan was trapped in a web of expectation and his own desires.

There are, however, more conspiratorial whispers preserved in some traditions. A few later accounts hint at internal plotting, suggesting that factions hoping to promote a particular successor might have welcomed, or even hastened, Ögedei’s passing. Such claims are difficult to substantiate and often emerged in highly politicized contexts, where discrediting rival lines became a matter of survival. No clear, contemporary evidence of poisoning or assassination has been found. In a sense, the theory of murder underestimates the more banal, and yet more historically plausible, culprit: the long, grinding damage of excess and strain.

Regardless of the medical detail, the impact is beyond question. The death of ögedei khan at Karakorum rippled outward in widening circles, touching not only the princes jostling for power, but also distant populations who would never know his name and yet would live, or die, because of the altered course of Mongol policy after him.

Karakorum in Mourning: Rituals, Oracles, and Political Theater

In the days following Ögedei’s death, Karakorum must have been transformed. The capital, still relatively young, turned into a stage on which grief, ritual, and politics intermingled inextricably. The Mongols believed that the souls of great rulers joined the spirits of their ancestors, dwelling in the Eternal Blue Sky that arched above the steppe. But before the Great Khan could join them, proper rites had to be performed, and his body had to be prepared for its final journey.

Accounts from later generations describe how the bodies of khans were transported by solemn cortège to secret burial sites, often guarded by elite escorts. Along the way, it is said, anyone unfortunate enough to witness the passage was put to death to maintain the secrecy of the location—a tradition that may be more legendary than literal, but speaks to the aura of untouchable sanctity surrounding the khan’s remains. For Ögedei, similar protocols likely applied. Selected nobles and guards would accompany the body, while shamans chanted, burned incense, and offered libations to guide the ruler safely into the next world.

Within Karakorum itself, temples and shrines—Buddhist, Daoist, and others—would have held their own ceremonies. Foreign visitors might have watched, uncertain of the precise meanings but deeply aware of the gravity of the moment. Artisans produced mourning garments, banners, and emblems; musicians played mournful tunes in the palace grounds. Yet beneath the outward expressions of grief pulsed another, more calculating undercurrent. For some, the death of ögedei khan was a personal loss. For others, it was an opening.

Meetings were convened in inner chambers. The senior princes, generals, and the widowed khatun, Töregene, gathered to discuss what must happen next. Their faces were streaked with tears, or at least arranged into suitable expressions of sorrow. But simultaneously, alliances were being reaffirmed—or broken. Old grievances resurfaced. Promises made by Ögedei about succession and the distribution of power were suddenly objects of contention rather than settled facts.

Shamans and oracles were also drawn into the political process. Their interpretations of omens and divine will could be invoked to justify one course of action over another. Should the empire immediately convene a kurultai to choose the next Great Khan? Should rule pass temporarily to a regent? Which branch of the family had the strongest spiritual backing? The boundary between the sacred and the political, so often porous in medieval societies, was especially fluid here. To question a chosen leader’s legitimacy could be framed as resisting the very order of the heavens.

Thus Karakorum in mourning was no simple portrait of unified sorrow. It was a crucible, where grief burned away illusions and left the raw metal of power to be hammered into a new, uncertain shape.

The Halt of the Mongol Thunder in Europe

While Karakorum wrapped itself in mourning and intrigue, another drama was unfolding thousands of kilometers away. In the spring and early summer of 1241, Europe had seemed on the verge of annihilation. Mongol armies under Batu and Subutai had crushed a coalition of Polish and German forces at Legnica, then turned south to deal a devastating blow to the Hungarian kingdom at the Battle of Mohi. Villages burned, monasteries were looted, and royal courts contemplated flight. Chroniclers wrote of “a people from the East” whose ferocity surpassed anything seen since the days of Attila.

Then, almost as suddenly as they had come, the Mongols began to pull back. They conducted further raids in 1242, ravaging parts of Hungary and the Balkans, but the feared advance into the heart of Western Europe—toward Vienna, perhaps even toward Rome or Paris—never came. European writers scrambled for explanations. Many framed the withdrawal as proof that God had intervened, turning back the pagan invaders in answer to desperate prayers. Others speculated about internal revolt among the Mongols, or imagined that natural disasters had struck their far-off homeland.

The reality, as modern scholarship has largely agreed, is simpler and more chilling. The death of ögedei khan required the presence of the leading princes at a kurultai to select his successor. Batu’s campaign in Europe, however successful, could not take precedence over the fundamental question of who would rule the empire. Summons went out, and Batu had little choice but to halt further expansion and begin a long, grueling withdrawal back toward the steppe.

Had Ögedei lived even a few more years, the map of Europe might look very different today. Subutai, the genius behind so many Mongol victories, had already begun planning deeper incursions into the German principalities and beyond. The logistical base in the Rus’ lands had been secured; Hungarian resistance was shattered. European armies remained disunited, their tactics ill-suited to Mongol warfare. The window of vulnerability was wide open.

The decision to recall the armies in order to resolve the succession crisis reveals something crucial about the Mongol Empire: its conquests, however brutal, were not random acts of raiding but part of a system that depended on coherent leadership from the center. Without a recognized Great Khan, the unity of the empire was at risk. Princes might ignore commands, carve out their own spheres of influence, or even turn their armies against one another. In such a context, continuing the campaign in Europe without settling the question of supreme authority would have been reckless.

For Europe, the death of ögedei khan was a reprieve granted by distant events they scarcely understood. For the Mongols, it was the beginning of a shift from relentless expansion to periodic bouts of hesitation, negotiation, and internal conflict. The thunder had not gone silent, but it had been interrupted.

Regency and Intrigue: Töregene Khatun Takes the Stage

In the immediate aftermath of Ögedei’s passing, power in Karakorum did not fall into a vacuum. It flowed, as water will, to the nearest available channel—in this case, the hands of his widow, Töregene Khatun. Far from being a mere ceremonial spouse, Töregene had long been an active participant in court politics, building networks of support among officials and religious leaders. With the throne empty and the princes scattered across the empire, she seized the opportunity to act as regent.

Her position was both precarious and potent. On the one hand, Mongol tradition did allow women of the royal family, particularly widowed khatuns, to act as stewards of power in times of transition. On the other, she faced suspicion and hostility from some male relatives, especially those loyal to other branches of the family. Töregene’s central aim quickly became clear: to secure the succession for her son, Güyük, against competing claims.

As regent, she initiated a series of purges and policy shifts. Many of Ögedei’s closest advisers were removed, exiled, or executed, especially those who opposed her or had favored a different candidate for succession. In their place, Töregene promoted her own allies, including influential Muslim administrators. This period saw an intensification of court intrigue, as complaints and accusations were wielded as weapons in the struggle for position. What had been a relatively balanced advisory structure under Ögedei tilted rapidly toward the regent’s faction.

Foreign envoys arriving in Karakorum during these years encountered a court that was both impressive and unsettled. Some described enormous tents draped with rich fabrics, banquets laden with food, and translators shuttling between languages—Mongolian, Persian, Chinese, Turkic, even Latin. But beneath the surface spectacle, everyone knew that the real question had not yet been answered: who would be proclaimed the next Great Khan at a universally recognized kurultai?

Töregene delayed that assembly. Officially, the postponement could be justified by the need to gather distant princes and ensure that all major branches of the family were represented. Unofficially, delay served her strategy well: it allowed more time to consolidate her network, neutralize opponents, and build the case for Güyük’s elevation. In the meantime, the empire did not stop functioning—taxes were collected, campaigns continued on some frontiers, and trade routes remained active—but decisions of the highest strategic importance were increasingly filtered through the lens of succession politics.

In many ways, Töregene’s regency demonstrated both the flexibility and fragility of the Mongol political system. It showed that women of the royal house could, under certain conditions, wield enormous authority. It also revealed how quickly the machinery of empire could be redirected toward internal maneuvering once the stabilizing figure of a Great Khan was removed.

Brothers, Cousins, and Enemies: The Succession Crisis Unfolds

The Mongol imperial family was both the engine of expansion and the seedbed of division. From Genghis Khan’s four principal sons—Jochi, Chagatai, Ögedei, and Tolui—descended a growing web of princes, each endowed with lands, warriors, and a sense of entitlement. Ögedei’s position as Great Khan had, for a time, kept these centrifugal forces in check. His death unleashed them.

The question of succession was complicated by older grievances. Jochi, the eldest son, had died before Genghis, but not before tensions had flared over his legitimacy. Rumors that he was not truly Genghis’s child, but rather the offspring of his mother’s earlier abduction, had long cast a shadow. Ögedei’s own selection as Great Khan had partly been a compromise between factions. Now the descendants of Jochi, including Batu, were powerful rulers in their own right, controlling the rich western domains that would later be known as the Golden Horde.

Chagatai’s line, based primarily in Central Asia, also had claims to prominence. However, Chagatai himself had previously agreed that Ögedei should be Great Khan, and his branch tended to push for adherence to Genghisid laws (the Yassa) more than for the throne itself. Tolui’s descendants, meanwhile, held significant military authority and would, in time, produce such giants as Möngke and Kublai Khan. During the regency, Toluid and Jochid interests did not always align with those of the Ögedeid faction centered on Töregene and Güyük.

Into this stew of rivalry, the death of ögedei khan dropped like a stone. Batu, still far in the west, was reluctant to rush back to Karakorum, knowing that entering the heartland could expose him to attacks from enemies at court. He preferred to consolidate his authority in the Russian and Pontic steppe regions, leveraging the uncertainty to carve out de facto independence. Chagatai died in 1242, adding yet another layer of complexity. The balance of power among the lines was in flux.

Töregene’s efforts to steer the succession toward Güyük alienated some potential allies. Batu, in particular, had a bitter personal rivalry with Güyük dating back to frictions during the European campaign. At a famous quarrel, Güyük had allegedly insulted Batu, leading to an altercation that only the authority of Ögedei and others had kept from escalation. Now, with the Great Khan gone, those resentments festered. A Güyük khanate would likely marginalize Batu’s influence; conversely, a Batu-aligned candidate might shut Güyük out of supreme power.

Thus the succession crisis was not just about legal or customary order; it was about deeply personal animosities, regional interests, and competing visions of the empire’s future. Would the Mongols remain a unified, centrally commanded colossus, or would they evolve into a looser federation of khanates? The outcome of the post-Ögedei struggle would push them toward the latter, even if no one at Karakorum would have phrased it that way at the time.

The Long Road to Güyük: Kurultai, Delay, and Division

The institution of the kurultai was meant to provide a clear, collectively sanctioned method of choosing a Great Khan. All branches of the royal family—at least in theory—were supposed to attend or send representatives, and decisions made there carried the weight of sacred tradition. Yet, in practice, organizing such a gathering across the vast spaces of the Mongol Empire was a logistical nightmare, especially when participants had little incentive to cooperate promptly.

After Ögedei’s death, Töregene delayed convening the kurultai that would decide the next Great Khan for several years. This postponement allowed her regency to continue, but it also amplified tensions. Batu lingered in his western domains and did not hurry east. Some princes suspected that if they came to Karakorum without sufficient military backing, they might be coerced or sidelined. Others worried that a hasty assembly could be manipulated by Töregene’s faction. Suspicion fed delay, and delay fed suspicion.

Only in 1246, after years of wrangling, were the conditions finally deemed ripe—or at least less dangerous—for a great assembly. Envoys from distant lands attended, including representatives of the papacy in Europe. They traveled across a landscape still marked by the scars of Mongol conquest, carrying letters that combined humble flattery with veiled warnings. At the kurultai itself, rituals unfolded beneath the open sky: horses were sacrificed, prayers were offered, and candidates maneuvered behind the scenes.

Töregene’s efforts bore fruit. Güyük, Ögedei’s son, was chosen and enthroned as Great Khan. From the outside, especially to foreign observers, the succession might have looked like a seamless continuation of Genghisid rule. But the process that led there revealed fissures. Batu did not attend in person, sending representatives instead. His absence sent a signal: while he recognized the formal decision, his commitment to Güyük’s authority would be conditional at best.

Güyük’s reign, brief and troubled, cannot be understood without reference to the death of ögedei khan that had made it possible. He spent much of his time attempting to reassert central authority, rolling back decisions made by Töregene and punishing some of her allies. Relations with Batu deteriorated further, threatening to spark open war between Jochid and Ögedeid branches. The empire that had once moved outward in near-unanimous campaigns now risked turning inward in fratricidal conflict.

Thus the long road from Ögedei’s death to Güyük’s enthronement was less a bridge than a fault line. It showed that the legitimacy of the Great Khan could no longer be taken for granted and that the very mechanisms meant to preserve unity could also become arenas of division.

Shifting Frontiers: How the Death Reshaped Eurasian Politics

Seen from the perspective of the wider world, the death of ögedei khan functioned like an invisible hand altering the political map of Eurasia. For the kingdoms, sultanates, and principalities at the edges of Mongol power, his passing created momentary breathing spaces, unexpected opportunities, and new dangers. Each region experienced the aftershocks in its own way.

In Eastern Europe, the withdrawal of Mongol forces in 1242 allowed Hungary and Poland to begin a painful process of recovery. King Béla IV of Hungary, labeled “the second founder of the state” by later generations, undertook wide-ranging reforms: rebuilding fortifications in stone, encouraging the settlement of new populations, and rethinking military organization to better confront steppe threats. None of this would have been possible had Mongol armies remained in place under a stable, aggressive central command.

In the Rus’ lands, devastated in the initial onslaught, a different pattern emerged. Here, Mongol domination persisted in the form of the Golden Horde, which collected tribute and shaped the political evolution of principalities like Moscow and Vladimir. Batu’s relative autonomy in the wake of Ögedei’s death meant that these western territories evolved increasingly under Jochid, rather than universal imperial, priorities. Over the long term, the political culture of northeastern Europe would bear the imprint of this semi-independent Mongol overlordship.

Further south, in the Islamic world, the fluctuating intensity of Mongol campaigns was also affected. The Khwarazmian lands had already been crushed by Genghis, but future assaults on the Abbasid caliphate and the heartlands of the Middle East would unfold under later khans. Had Ögedei lived longer, he might have directed more immediate, concentrated attention toward these centers of Islamic power. Instead, the post-Ögedei years saw a more uneven pattern of campaigns, as rival generals and branches of the family balanced external conquest against internal positioning.

China, too, was drawn into this shifting equation. The collapse of the Jin dynasty during Ögedei’s life opened vast territories in northern China to Mongol rule. Yet the ultimate conquest of the Southern Song and the founding of the Yuan dynasty would not occur until the reign of Kublai Khan, a later descendant. Some historians have speculated that a longer-lived Ögedei, maintaining firmer central control, might have prioritized the rapid completion of Chinese unification over western adventures. Instead, energy and resources were partly siphoned off by the need to manage and negotiate succession politics.

In a broader sense, the death of ögedei khan subtly shifted the Mongol Empire from a phase of aggressive, centrally coordinated expansion into one of regional consolidation and gradual fragmentation. The empire did not collapse overnight—far from it. For decades, Mongol forces would continue to shatter cities and expand frontiers. But the drive to expand in all directions at once, under a single unquestioned leader, never truly returned.

Everyday Lives in Turmoil: Traders, Peasants, and Captives

Political histories of great khans and sweeping campaigns often risk overlooking the lives of ordinary people who moved within, or beneath, these tectonic shifts. The death of ögedei khan, though decided in palaces and kurultais, altered the fates of countless individuals who never saw Karakorum and had no say in imperial councils. To appreciate its full impact, one must descend from the level of kings and generals to the choked roads and shattered fields of the thirteenth century.

Consider the merchants who plied the Silk Road. Under Ögedei, many had found new opportunities in the relative safety imposed by Mongol rule. Caravanserais were established or refurbished; bandits were hunted down; customs systems, however onerous, were at least somewhat standardized. The news of the Great Khan’s death introduced new uncertainties. Would taxes rise under his successor? Would certain routes become more dangerous as regional power brokers tested the limits of central authority? As Güyük’s reign unfolded with increasing hostility toward some of Töregene’s allies, merchants associated with particular factions might find themselves targeted or disadvantaged.

In the countryside of Hungary or the fields around Kiev, peasants faced a different reality. For them, the withdrawal of Mongol armies after 1241–1242 meant an end to the immediate terror of raids, but not an end to suffering. Villages lay in ruins; crops had been burned; survivors grappled with famine and disease. Church records and charters from these regions speak of abandoned lands and efforts to resettle them. Yet, had the Mongols pushed further, these fragile efforts could have been swept away again. The sudden cessation of conquest allowed governments, however weakened, to begin patching their realms back together.

Then there were the captives: artisans, scribes, engineers, and skilled laborers taken from conquered territories and resettled in Mongol domains. Ögedei’s Karakorum owed much of its nascent splendor to such enforced migration. The craftsmen who built stone structures, cast bronze, or worked in precious metals often came from far-off lands—China, Central Asia, the Islamic world. The death of ögedei khan likely filled them with dread. A new ruler might favor different projects, different communities, different administrators. Patronage networks could shift overnight, leaving some groups exposed to exploitation or dispersal.

Even within the nomadic heartlands, ordinary herders felt the change. The passing of a Great Khan was accompanied by large-scale feasts, sacrifices, and military musters. All of these demanded resources: animals to slaughter, supplies to transport, labor to build temporary encampments for visiting dignitaries. The kurultai that eventually elevated Güyük must have drawn men and herds from a wide radius, disrupting seasonal rhythms. And as rival factions jostled, local commanders might demand additional contributions, ostensibly in the name of the empire but in practice to strengthen their own positions.

Thus the death of ögedei khan was not only a matter of grand strategy. It seeped into the fabric of daily life, from the counting tables of Samarkand merchants to the plowed strips of Hungarian peasants, from the workshops of captured engineers to the winter pastures of Mongol shepherds. History’s turning points are rarely felt evenly, but they are felt.

Chroniclers, Myths, and Memory: How History Remembered Ögedei

Ögedei’s life and death did not vanish into the steppe winds. They were captured, reshaped, and sometimes distorted by writers working in very different cultural milieus. The way we understand the death of ögedei khan today owes much to a handful of sources, each with its own perspective.

The anonymous author of the Secret History of the Mongols, likely composed in the mid-thirteenth century for an internal Mongol audience, portrays Ögedei in a sympathetic light: loyal, generous, perhaps less formidable than his father but still a worthy successor. The text does not dwell morbidly on his end, focusing instead on his role in the unfolding Genghisid saga. Persian historians like Ata-Malik Juvayni and Rashid al-Din, writing from within the orbit of later Mongol dynasties in Iran, offer more detailed reflections. Rashid al-Din, in particular, sought to compile a comprehensive universal history that integrated Mongol narratives with those of older Islamic and Persian traditions. His account acknowledges Ögedei’s vices but also credits him with fostering order and relative justice within the empire.

European chroniclers, by contrast, encountered Ögedei mostly as a distant, terrifying name—“Emperor of the Tartars,” ruler of the horsemen who had shattered Christian armies. Matthew Paris, an English monk writing in the 1240s and 1250s, described the Mongols as apocalyptic invaders and noted the mysterious withdrawal from Europe after their initial conquests. For him, the Khan’s death, once reported, became a providential sign, though the specifics remained vague. He and others could only guess at the intrigues of Karakorum, imagining them through the lens of biblical kings and classical tyrants.

Over time, myths accrued. In some tales, Ögedei’s death was framed not as the natural consequence of excess, but as an act of heaven, punishing the Mongols for their cruelty. In others, it became a minor episode overshadowed by the later glories of Kublai Khan or the dramatic fall of Baghdad in 1258. National histories in Europe tended to emphasize heroic resistance to Mongol assault, casting the withdrawal as evidence of Christian resilience rather than of internal Mongol dynamics.

Modern historians, armed with critical methods and comparative sources, have tried to cut through such layers of bias. They compare the accounts of Juvayni, Rashid al-Din, Chinese dynastic histories, and archaeological evidence to reconstruct a more nuanced portrait. As one contemporary scholar has observed, “Ögedei’s reign was the hinge on which the door of Mongol world empire swung: at once consolidating his father’s legacy and revealing its inherent instabilities.” That hinge, once broken, could not be easily repaired.

Memory, in the end, is as much about the needs of those who remember as it is about the events themselves. For the Mongols, Ögedei became part of the sacred genealogy of Genghis’s descendants. For their foes, he was an emblem of an age when death rode from the east. For us, he stands at the center of a crucial transition—a man whose passing refracted through sources colored by fear, admiration, resentment, and hindsight.

If the Khan Had Lived: Plausible Paths Not Taken

Counterfactual history is a dangerous but sometimes illuminating exercise. To ask “What if?” is not to escape reality, but to sharpen our sense of how contingent reality truly was. What, then, might the world have looked like had the death of ögedei khan been postponed by a decade? What paths, dimly visible, closed forever on that winter night in 1241?

The most immediate speculation concerns Europe. If Ögedei had remained alive and in control, there is little reason to doubt that he would have authorized Subutai’s plans for deeper advances westward. The German principalities, fragmented and mutually suspicious, would have struggled to coordinate an effective response. The Kingdom of Bohemia, Austria, perhaps even the Italian city-states might have faced the full force of mounted archers and siege engines that had already proven devastating. Could the papacy have rallied a genuine pan-European crusade against the Mongols, or would rivalries between the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope have undermined such efforts? We cannot know—but the balance of probabilities tilts ominously toward further Mongol victories.

In the Islamic world, a longer-lived Ögedei might have accelerated campaigns against the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad. The city’s destruction in 1258 under Hülegü, a generation later, has often been seen as a decisive blow to Islamic political unity. Under Ögedei’s guidance, such an assault might have come earlier or taken a different form, potentially altering the timing and nature of the region’s transformation.

Within the Mongol Empire itself, continued rule by Ögedei could have delayed or moderated the factionalism that blossomed after his death. Batu and Güyük’s rivalry might still have existed, but under the watchful eye of a firmly established Great Khan, it would have been more difficult to translate personal animosity into open political fragmentation. The golden thread of central authority could have remained intact longer, with correspondingly tighter control over taxation, military deployments, and diplomatic relations.

China’s fate, too, hangs in this web of possibilities. Ögedei had already presided over the destruction of the Jin dynasty; it is conceivable that he would have pushed harder and earlier against the Southern Song, perhaps unifying China under Mongol rule before the mid-thirteenth century. In that case, Kublai’s later achievements might be perceived not as the founding of a new Yuan phase, but as the continuation of an earlier consolidation, with different cultural and administrative consequences.

Of course, such conjectures must be tempered by an awareness of internal limits. Even had he lived, Ögedei’s health problems and personal habits might have continued to erode his effectiveness. The strains of ruling a vast, multiethnic empire could have produced crises of a different kind: rebellions in Central Asia, overextension in Europe, or financial collapse in some regions. The Mongol system, built on conquest and the distribution of booty, had inherent vulnerabilities that no single ruler could entirely overcome.

Still, by contemplating these unrealized possibilities, we better grasp the enormity of what did occur. The death of ögedei khan was not simply the end of one man’s story; it was the cutting of multiple potential threads in the tapestry of global history.

Echoes Across Centuries: Why Ögedei’s End Still Matters

Standing at such a distance from the thirteenth century, one might wonder why the passing of a Mongol ruler in a steppe capital should still command our attention. Yet the echoes of that event resound, if faintly, in the structures of our modern world. Borders drawn in blood during and after the Mongol expansion contributed to the historical trajectories of Russia, China, Central Asia, and parts of Europe. Trade patterns established under Mongol protection—and later disrupted by their fragmentation—shaped the flow of goods and ideas across Eurasia.

The death of ögedei khan, by halting European campaigns and accelerating internal divisions, played a role in preserving a multipolar Europe, in which no single empire dominated the entire continent. That, in turn, nurtured an environment where competitive states could experiment, innovate, and fight, seeding the complex evolution that eventually produced the modern nation-state system. In the east, the eventual division of the Mongol Empire into distinct khanates laid the groundwork for later polities: Muscovy’s rise under the shadow of the Golden Horde, the emergence of the Yuan in China and its successors, the Ilkhanate in Iran with its own cultural syntheses.

On a more human level, Ögedei’s death reminds us of the vulnerability of power to the limitations of the body. An empire held together by the will and authority of a single individual is inherently precarious. The Mongols, with all their military prowess and political innovation, could not escape the basic biological fact that rulers age, sicken, and die. The tension between personal rule and institutional stability, visible so starkly in Karakorum in 1241, remains a recurring theme in world history, from absolutist monarchies to modern authoritarian regimes.

Finally, the story of this death—reconstructed from scattered chronicles, cross-cultural accounts, and archaeological hints—speaks to the craft of history itself. We rely on voices from the past that are incomplete, biased, and sometimes contradictory. As historian Thomas Allsen once emphasized, studying the Mongol Empire requires a “comparative use of sources” that respects their diversity while probing their silences. In doing so, we see not only the Mongols more clearly, but also ourselves: our tendency to simplify, to mythologize, to see turning points where perhaps there were only gradual shifts, and yet to be right, sometimes, that a single night can indeed change the world.

And so the cold air over Karakorum on December 11, 1241, still seems to carry meaning. In the extinguishing of a life worn down by conquest and excess, we glimpse both the height of Mongol power and the beginning of its transformation into something more fractured, more familiar, and ultimately more human.

Conclusion

On that winter night in Karakorum, the Mongol Empire appeared indomitable. Its armies thundered across continents; its caravans threaded a nearly global web of trade; its rulers commanded fear and tribute from China to Eastern Europe. Yet the death of ögedei khan revealed how much of this magnificence depended on the fragile body and contested authority of one man. His passing halted the westward momentum that had terrorized Europe, opened a turbulent arena of succession politics, and nudged the empire from unified expansion toward regional fragmentation.

Seen up close, this turning point is textured with human details: the whispered worries of physicians, the determination of Töregene Khatun to secure her son’s future, the rivalries among princes, the anxiety of merchants and peasants watching imperial winds shift. Seen from afar, it marks a structural change in Eurasian history, preserving space for a plural Europe, reshaping the destinies of Rus’ principalities, influencing the timelines of Chinese unification and Middle Eastern upheaval. Ögedei’s life, from a boy on the steppe to the ruler of the world’s largest land empire, was remarkable; his death, quiet but seismic, proved just as consequential.

History rarely moves in straight lines. It bends around contingencies—illnesses, personalities, accidents, and decisions made under pressure in places like Karakorum’s palaces. The story of Ögedei’s final days and their aftermath is a stark reminder that empires, no matter how vast, rest on uncertain foundations. In tracing the ripples from his last breath to the rearranged map of Eurasia, we learn not only about the Mongols, but about the perennial vulnerability and complexity of power itself.

FAQs

- Who was Ögedei Khan?

Ögedei Khan was the third son of Genghis Khan and the second Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, ruling from 1229 to 1241. He oversaw the consolidation of his father’s conquests, the capture of the Jin dynasty in northern China, and the massive western campaigns that reached into Eastern Europe. - When and where did Ögedei Khan die?

He died on December 11, 1241, in the Mongol capital of Karakorum, located in what is now central Mongolia. His death occurred while Mongol armies were still campaigning in Eastern Europe. - What caused the death of Ögedei Khan?

Most historians believe that chronic alcoholism and related health problems led to his death, possibly through liver failure, heart failure, or stroke. Medieval sources emphasize his heavy drinking and record failed attempts by advisers to limit his alcohol intake. - How did Ögedei Khan’s death affect the Mongol invasion of Europe?

His death prompted a recall of leading princes and commanders to participate in a kurultai to choose the next Great Khan. As a result, campaigns in Eastern Europe were halted, and Mongol forces withdrew from areas like Hungary and Poland, sparing Western Europe from deeper invasion at that time. - Who ruled after Ögedei Khan died?

After his death, his widow Töregene Khatun served as regent, effectively governing the empire while maneuvering to secure the throne for their son, Güyük. In 1246, after prolonged delays and political infighting, Güyük Khan was elected Great Khan at a grand kurultai. - What role did Töregene Khatun play in the succession?

Töregene Khatun played a central role, using her position as regent to remove opponents, promote allies, and delay the succession until she could ensure Güyük’s election. Her regency highlights the significant, though often overlooked, political influence of royal Mongol women. - Did the Mongol Empire begin to decline after Ögedei’s death?

The empire did not immediately decline—it continued to expand and devastate new regions for decades. However, his death marked a shift from unified expansion under a strong central authority to a more fragmented system of semi-independent khanates, sowing the seeds for later divisions. - How did Ögedei’s death impact everyday people in the empire?

For ordinary people—peasants, traders, artisans, and captives—his death brought uncertainty. Tax systems, patronage networks, and military demands could change abruptly as new factions gained power. In some regions like Eastern Europe, the withdrawal of Mongol armies allowed reconstruction; in others, such as the Rus’ lands, Mongol control hardened under regional khanates. - What are the main historical sources for Ögedei’s life and death?

Key sources include the Secret History of the Mongols, Persian works such as Juvayni’s History of the World Conqueror and Rashid al-Din’s Compendium of Chronicles, various Chinese dynastic histories, and European chronicles like those of Matthew Paris. Each source reflects its author’s context and biases. - Why is the death of Ögedei Khan considered a major turning point?

It is seen as a turning point because it halted further Mongol advances into Europe, triggered a protracted succession struggle, and contributed to the gradual fragmentation of the Mongol Empire. The political and military choices shaped by his absence influenced the long-term development of Europe, Russia, the Middle East, and East Asia.

External Resource

Internal Link

Other Resources

- Encyclopaedia Britannica – general search for the exact subject

- Google Scholar – academic search for the exact subject

- Internet Archive – digital library search for the exact subject