Table of Contents

- A River at Night: The Last Journey of Li Po

- A Child of Turbulent Times: China Before 762

- From Exile to the Imperial Court: The Making of a Poet Immortal

- Wine, Moonlight, and Myth: The Legend That Shaped His Death

- Historical Records and Quiet Rooms: What Really Happened in 762

- Illness, Old Age, or the River? Competing Theories of His Final Hours

- Li Po and the An Lushan Rebellion: Poetry at the Edge of Collapse

- Friends, Rivals, and Witnesses: Du Fu and the Circle Around Li Po

- The Political Echo: Court Intrigues and the Fate of a Wayward Genius

- The Human Cost: Exile, Disillusion, and the Weight of a Life’s Work

- From Riverbank to Legend: How the Story of His Death Took Shape

- Across Dynasties: How Later Eras Reimagined Li Po’s Final Night

- Beyond China: The Global Afterlife of a Tang Poet

- Memory in Stone and Ink: Shrines, Anthologies, and Schoolroom Recitations

- The Poet and the Moon: Themes of Mortality in Li Po’s Work

- History, Myth, and Evidence: Reconstructing the Death of Poet Li Po

- Conclusion

- FAQs

- External Resource

- Internal Link

Article Summary: In the late summer or autumn of 762, as the Tang dynasty staggered from rebellion and civil war, the death of poet Li Po became more than a biographical event—it became a legend. This article follows his journey from obscure frontier childhood to luminous fame, through exile, political suspicion, and the frailty of his last years. We confront the famous myth that the death of poet Li Po came when he drowned trying to embrace the reflection of the moon in the Yangtze, and we place that story beside quieter but more persuasive historical accounts. Along the way, we explore how the political upheavals of the An Lushan Rebellion shaped the life, work, and eventual death of poet Li Po, and how his contemporaries, especially Du Fu, bore witness to his genius and decline. The narrative traces how later dynasties, from Song scholars to Qing emperors, retold the death of poet Li Po to mirror their own anxieties and ideals. We follow his influence as his poems crossed borders into Japan, Europe, and the modern world, reshaping ideas of nature, solitude, and intoxication in verse. Ultimately, the article argues that the death of poet Li Po cannot be understood without seeing how myth, political memory, and personal grief fused into a single enduring story. What remains is not merely a date in 762, but an ever-renewed conversation between history and imagination.

A River at Night: The Last Journey of Li Po

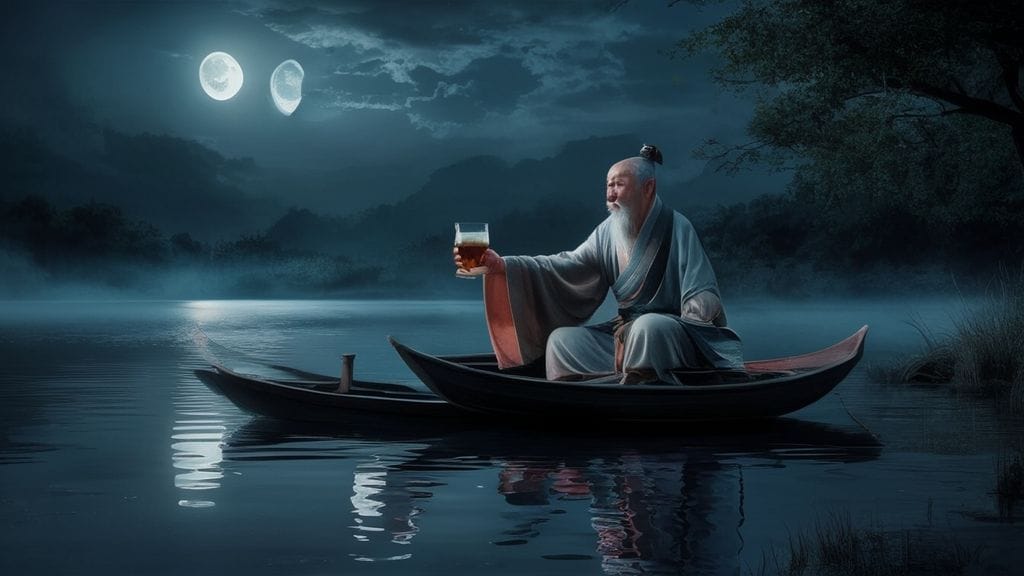

On some nights in Chinese imagination, the river is not just water but a long dark mirror, carrying the moon on its back. It is here, on such a river in the year 762, that one of the most enduring legends of the Tang dynasty comes to rest: the death of poet Li Po. In the story that generations would come to cherish, the old poet, drunk on wine and moonlight, stepped into a boat under the glittering sky. The world was quiet except for the dip of oars, the ripple of water, and the echo of his own recited lines drifting off into the dark.

He looked down. On the river’s surface floated the perfect disk of the moon, an image he had pursued with his words his entire life. For decades he had toasted it, scolded it, befriended it in lonely exile. Now, as the tale goes, he reached for it with his arms, trying to embrace the cold, silver presence that had followed him wherever he went. The boat tilted. The river swallowed him whole, and the death of poet Li Po became, in the popular imagination, the final union of man, moon, and water.

But this was only the beginning of his story’s afterlife. Behind the intoxicating charm of that image lies a harsher reality: a China torn by rebellion, an empire exhausted, and an old man weakened by exile and illness. The real death of poet Li Po did not happen in the imperial capital but far away, in the inland province of Dangtu in present-day Anhui, where he is believed to have died of sickness after years of wandering and political disgrace. The romantic drowning is a later invention, perhaps too beautiful to abandon, perhaps necessary to a civilization that wanted to remember its greatest romantic poet as a figure carved from moonlight rather than from fever and fatigue.

Yet the gap between myth and record is not a void; it is a dense field of memory, politics, and longing. To understand how the death of poet Li Po turned into legend, we must trace the river of his life backward: to the frontier town where he was born, to the courts where he dazzled and offended, to the battle-scarred landscapes of the An Lushan Rebellion. Only then can we see why his end still grips the imagination, over a millennium later, as if he had slipped beneath the surface only yesterday.

A Child of Turbulent Times: China Before 762

Long before the death of poet Li Po became a question for historians, the world he inhabited was an experiment in imperial grandeur. The Tang dynasty, founded in 618, had, by the early 8th century, turned Chang’an into one of the largest and most cosmopolitan cities on earth. Envoys arrived from Central Asia and beyond, merchants crowded the markets with spices, textiles, and horses, and along with Buddhist monks and foreign traders came new languages, fashions, and religious debates. It was a world intoxicated with its own possibilities, and yet one that carried within it the seeds of fracture.

Li Po (also known as Li Bai) was born around 701, likely in Suyab in Central Asia or in the frontier regions of what is now Sichuan. His family history is murky—possibly exiled aristocrats, possibly merchants, possibly both. What matters is that he grew up not at the empire’s center but on its edge, where borderlands met caravan trails and where Chinese, Turkic, and Central Asian cultures mixed. The boy who would later fill his poems with mountains, torrents, and wild spaces learned early that civilization was always one or two ridgelines away from wilderness.

Tang China at the time of his youth had not yet endured the shattering of the An Lushan Rebellion, but it was already vibrating with tensions. The military frontier governors had grown powerful; eunuchs wielded significant influence in the imperial court; factions whispered against one another. The poet would one day sing of wine and clouds, but the background hum of politics was never absent. Scholars, nobles, and commoners alike lived in the shadow of a fierce meritocratic ideal: the civil service examinations, which promised that talent, not only birth, could lead to office. Li Po, famously, would never enter that path, a fact that would help shape both his freedom and his ruin.

It is astonishing, isn’t it, that the man who could have been a statesman chose instead a life at a slant to officialdom. Where many of his contemporaries laboriously memorized Confucian classics for the exam halls, Li Po cultivated swordsmanship, daoist practices, and the art of spontaneous verse. Later, imperial historians would venerate him as an immortal of poetry, but in his own youth he was an anomaly, moving through a China uneasy with difference and yet drawn to brilliance wherever it appeared.

By the time he reached adulthood, the empire under Emperor Xuanzong glowed at its zenith—population swelling, borders expansive, the arts flourishing in palace and tavern alike. Yet beneath that gleam, a slow accumulation of grievances and rivalries built toward catastrophe. The story of the death of poet Li Po in 762 is inseparable from this broader arc, for he lived long enough to see the edifice that had dazzled his youth begin to crack and then partially collapse around him.

From Exile to the Imperial Court: The Making of a Poet Immortal

In his twenties and thirties, Li Po wandered. The records show him on the move constantly: leaving Sichuan, drifting down great rivers, visiting monasteries, attaching himself briefly to patrons, then slipping away again. He married, but the marriage did not anchor him. He joined literary circles, then disappeared for years at a time into remote landscapes. He was, in a sense, rehearsing for his own legend—living as if the empire were a vast stage on which he could enter and exit at whim, more spirit than citizen.

His poetry from this period bears the freshness of that life. He wrote of mountain ascents that felt like religious experiences, of drinking beneath blossoming trees with friends who might never meet again, of waking from dreams where he had flown among immortals. His diction was often startlingly direct, his imagery almost cinematic: “We sit together, the mountain and I, until only the mountain remains.” He wrote as someone who, even while alive, suspected himself half-gone already, a transient between worlds.

Then, in his early forties, came the invitation that would turn him from provincial genius into an imperial sensation. Around 742, he was summoned to the capital Chang’an, allegedly at the recommendation of high-ranking officials impressed by his reputation. Imagine the journey: the river boat entering the city’s vicinity, the distant walls growing larger, the great markets humming, the poet—long accustomed to mountain hermitages and border towns—suddenly confronted with the full splendor of Tang power.

At court, he dazzled and offended in equal measure. Accounts describe him arriving drunk in audience, composing verses on the spot that sent courtiers into stunned silence and delight, and relying on the emperor’s fondness to escape censure. Emperor Xuanzong, a patron of the arts, seems to have been amused and charmed. For a brief moment, Li Po tasted what it meant to be the lyric voice of an empire, his words echoing in marble halls instead of straw-roofed inns.

Yet behind the celebrations, dangers coiled. He lacked the instinct for careful self-preservation that court life required. He aligned with powerful political figures, such as the general Gao Lishi and others, and he mocked, intentionally or not, those who valued decorum more than genius. It was as if the very qualities that made him electrifying as a poet—his spontaneity, his indifference to rank, his tendency to see the world in exaggerated contrasts—made him ill-suited to the delicate, poisonous intrigues surrounding the throne.

Within a few years, he was out. Whether through factional machinations or simple exhaustion with his unpredictability, the court let him go. The fall was not yet into prison or exile, but into something perhaps more corrosive: irrelevance. For a man who had briefly seen his own words shine in the imperial gaze, the loss must have felt like a personal eclipse. It set the pattern for the rest of his life: flashes of patronage and recognition, followed by displacement and wandering. The stages were being set for the political storms that would eventually entangle him more brutally.

Wine, Moonlight, and Myth: The Legend That Shaped His Death

Why did later ages choose to remember the death of poet Li Po not as a quiet passing in a provincial town, but as a spectacular drowning while grasping at the moon’s reflection? The answer lies partly in his verses, which had, from early on, entwined wine, rivers, and celestial bodies into a single recurrent dream.

Li Po wrote more poems about drinking wine than perhaps any other major poet in Chinese history. In one famous piece, later rendered into English as “Drinking Alone by Moonlight,” he imagines himself with two companions: his shadow and the moon. The three of them drink and dance; they separate when the night ends, but promise to reunite beyond the bounds of mortality. It is not a large leap from that poem to the idea that, in the end, he sought literal union with that quiet, luminous friend in the sky.

Medieval Chinese biographical traditions did not sharply separate history from moralized storytelling. A good life was expected to end with a fitting scene, a tableau that captured the person’s essence. A statesman might die at his desk, still working for the realm; a recluse might vanish into the mountains; a martyr might spill his blood in righteous protest. Li Po, the romantic Daoist-tinged wanderer, the drunken sage of rivers and moonlight—how else, people asked centuries later, could he possibly have died?

So a narrative crystallized. It appears clearly in later texts rather than in the earliest accounts, and it likely drew upon older tropes about poets and sages whose passion exceeded ordinary bounds. The story was too good to subject to scrutiny. Children in later dynasties would learn that the death of poet Li Po was an act of intoxicated transcendence, and countless painters would depict the scene: a figure in flowing robes leaning out of a boat, arms open to the shimmering moon on the water, fate approaching like a silent wave.

And yet document collections such as the Tang histories and local gazetteers offer no solid support for that specific manner of death. What they speak of, instead, is an aging man, weakened and traveling, perhaps succumbing to illness. The historian’s task is not to erase the legend—because it, too, is part of his cultural life—but to place it alongside the more prosaic, and perhaps more human, account. For if he died in a small town bed in Dangtu, without fanfare, that does not make his end less moving. It might, in fact, make the distance between his soaring verse and his mortal limits even more poignant.

Historical Records and Quiet Rooms: What Really Happened in 762

What do we actually know about the death of poet Li Po? The earliest and most authoritative sources do not offer dramatic river scenes. Instead, they speak tersely of illness and age. The “Old Book of Tang” (Jiu Tang Shu) and the “New Book of Tang” (Xin Tang Shu), compiled in the 10th and 11th centuries respectively, provide entries on Li Bai that, while brief, remain our key starting points.

These accounts place his death in 762, the same year the An Lushan Rebellion’s second phase effectively ended with the death of its later leader, Shi Siming’s son Shi Chaoyi. The empire was shattered and reeling; famine, depopulation, and military devastation haunted the land. In that atmosphere, a provincial poet’s passing, even one of his stature, did not command the full apparatus of state attention. According to later local traditions, Li Po died in Dangtu County, in today’s Anhui province, where he had taken refuge with relatives or patrons after receiving a partial pardon from his earlier sentencing to exile.

No eyewitness diary survives to tell us about his last days. We reconstruct them from scattered mentions, from letters by contemporaries, and from the fact that a tomb and memorial sites gradually formed in and around Dangtu. Some sources suggest he was ill for some time; others imply a more sudden decline. One late anecdote speaks of him composing lines until nearly the end, as if refusing to set down the brush until his own hand failed him.

The historian and critic Qian Zhongshu, writing in the 20th century, stressed the lack of reliable evidence for the moon-drowning legend, calling attention instead to the sober record of a natural death. Modern scholars tend to agree that the story of the death of poet Li Po by drowning is a “literary truth” rather than a factual one—a distillation of his persona rather than a report of an event. Yet they also note that even fabricated details can reveal how later ages wanted to see him: not as a tired exile succumbing to disease, but as a man whose art and life remained indivisible until his final breath.

It is worth pausing on the quietness of this historically plausible death. No imperial physicians were summoned from Chang’an. No court decrees proclaimed mourning. He was, after all, a man who had once been sentenced to exile on charges of involvement in rebellion, and though pardoned, he remained politically marginal. In that sense, his end mirrors the fate of the Tang itself: great brilliance dimmed, still flickering in corners, yet far from the stable center it once claimed.

We see him now in a small guest room or family house, perhaps near the sound of the Yangtze but not upon it, feeling the weight in his chest, the weakness in his limbs. Around him, the friends and relatives of a diminished circle. Outside, soldiers and refugees still moved along the roads, the empire’s pain unresolved. Inside, the man whose lines had soared over mountains folded back into the body that had carried him so restlessly across the map.

Illness, Old Age, or the River? Competing Theories of His Final Hours

The death of poet Li Po has provoked speculation not just because of the legend of drowning, but because the surviving sources are so laconic. This silence has invited later interpreters to project their own understandings of illness, morality, and fate onto his final hours.

One cluster of theories centers on chronic illness, possibly exacerbated by heavy drinking. His lifelong enthusiasm for wine, while romanticized in poetry, likely took a physical toll. Some medical historians suggest liver disease; others point to the strain of decades of travel, poor diet, and emotional upheaval. Death in one’s early sixties was not uncommon in Tang China, particularly after years of political and social instability. From this perspective, his passing would have been unremarkable for a man of his age and circumstances—except, of course, that he was Li Po.

Another line of speculation emphasizes the psychological weight of his later years. After the courtly glory had faded, after exile sentences and narrow escapes, he must have seen his world contract. The dream of being recognized as both poet and statesman had withered. While there is no evidence of self-harm, some scholars read a growing melancholia in his late poems, a sharper sense of mortality and of the vanity of worldly hopes. Death, in this reading, was a kind of release from a life that had already experienced several symbolic deaths: of youthful ambition, of political hope, of imperial stability.

Then there is the river theory, not as pure myth, but as a possibility distorted by retelling. Could he have fallen from a boat while traveling in poor health? Could a minor, accidental drowning have been transformed over centuries into an aestheticized embrace of the moon? Without documents we cannot know, but the logic of legend-building suggests that if any such incident occurred, it would have been eagerly moralized and elaborated, its banal details polished away.

The sober view points us back to illness. To imagine him dying in bed, sweating with fever or struggling for breath, is to bring him closer to us, not farther. There is a cruel yet honest dignity in such an end: the body asserting its limits over a spirit that had so often soared beyond them in verse. The drama of the death of poet Li Po, from this angle, lies not in the manner of his last heartbeat, but in the immense contrast between the magnitude of his imaginative universe and the small, ordinary room that likely held his final struggle.

For the historian, this contrast is instructive. It reminds us that greatness does not grant an exemption from frailty. It also hints at why later tellers of his story, unsatisfied with the image of a genius felled by ordinary disease, would turn back to the rivers and the moon for a more fitting stage on which to let him fall.

Li Po and the An Lushan Rebellion: Poetry at the Edge of Collapse

No account of the death of poet Li Po can ignore the wider cataclysm that shook his adult life: the An Lushan Rebellion of 755–763. This massive uprising, led first by the frontier general An Lushan and then by his successors, tore the Tang empire in half, resulting in millions of deaths and permanently weakening central authority. It was both civil war and regional revolt, fueled by ethnic tensions, court corruption, and military overreach.

When the rebellion broke out, Li Po was no longer at the height of his courtly favor. He moved among different patrons, navigating a landscape that was becoming increasingly dangerous. Armies marched, cities changed hands, and loyalties were tested. The imperial family itself fled Chang’an at one point, and the old certainties of Tang grandeur collapsed into a chaos of competing warlords and provincial governors.

Li Po’s own political involvement came to a head when he associated with the Prince of Yong, a member of the imperial house who was caught up in a failed power struggle during the rebellion. In the paranoia of war, such associations were deadly. Li Po was arrested and charged with treasonous complicity. The sentence, at one point, was death. That he escaped execution and had his sentence reduced to exile was, by all accounts, a near thing.

In this crucible, the romantic poet confronted the blunt machinery of state violence. His poems from the exile period, though fewer, carry the marks of shock and bitterness. He wrote of ruined landscapes, of armies trampling fields, of towers where candles burned all night because no one dared sleep. The man who had once written of transcendent drunkenness now wrote, at times, of a more sober and unrelenting pain.

Though he eventually received a partial pardon, the experience changed him. The journey toward his final resting place in Dangtu began here, on the road out of the center of power, marked as a once-favored but now suspect figure. The death of poet Li Po in 762 thus cannot be detached from the end of a world he had known; as the rebellion ground on, he lived, wrote, aged, and finally faded in a China that no longer resembled the flourishing empire of his youth.

The rebellion also shaped how later historians framed his life and death. To some, he was a casualty—if not physically, then spiritually—of that national disaster, a voice of the high Tang whose song ended as the empire’s harmony broke. To others, he was an emblem of survivorship, proof that the imagination could outlive even the worst conflagrations. In both readings, 762 marks not just a personal endpoint but a milestone in the long decline of Tang authority.

Friends, Rivals, and Witnesses: Du Fu and the Circle Around Li Po

It is impossible to talk about Li Po without invoking Du Fu, his near-contemporary and, in many eyes, his equal or even superior as a poet. Where Li Po was the heavenly immortal—soaring, impulsive, intoxicated—Du Fu was the grounded historian of suffering, careful in craft, attentive to social detail. The two men met at least once, perhaps twice, and their brief companionship has become one of the most cherished episodes in Chinese literary lore.

For Du Fu, who lived through the same cataclysms of rebellion and displacement, the death of poet Li Po was a deeply personal blow. In one of his elegiac poems, he writes of Li Po as an immortal swallowed by the world’s dust, a bright star dimmed by a violent age. His verses about Li Po are among the earliest testimonies that move beyond official biography into the realm of grief-stricken remembrance. Through them, we catch glimpses of the man behind the legend: charming, erratic, sometimes exasperating, always blazing with talent.

Their friendship was brief in time but vast in influence. Later generations would pair them as “Li-Du,” twin peaks of Tang poetry. Yet their trajectories diverged sharply. While Li Po’s posthumous image drifted toward the ethereal and mythologized, Du Fu’s tended to be anchored in the historical and moral. This contrast meant that when Du Fu mourned him, he did so not as a worshipper of a demigod, but as a fellow sufferer in an age of war.

Beyond Du Fu, other contemporaries also left traces of their encounters with Li Po. Letters, anecdotes, and occasional verses record evenings of drinking, debates about Daoism and Confucianism, arguments over policy, and long separations. Some regarded him as irresponsible; others saw in him a purity of artistic purpose that court life could only corrupt. Together, their testimonies provide a mosaic: no one piece complete, but collectively revealing.

These witnesses matter for our understanding of his death because they humanize him. They remind us that when the news of his passing spread—however slowly, by foot and riverboat—people who had laughed with him in taverns and stood beside him in mountain temples felt true loss. The death of poet Li Po was not, for them, a line in a chronicle; it was the disappearance of a singular voice from their own tangled lives.

The Political Echo: Court Intrigues and the Fate of a Wayward Genius

Li Po’s life placed him repeatedly at the edge of political whirlpools. At court, his free manner and closeness to Emperor Xuanzong aroused envy and resentment. Later, his association with the Prince of Yong during the An Lushan Rebellion almost cost him his life. These episodes did not end with his exile; they cast a long shadow over how the state remembered him after his death.

In imperial China, posthumous reputation was often as much a matter of political decision as of literary evaluation. Titles could be granted or revoked, biographies in official histories could praise or condemn. That Li Po appears in the Tang histories at all is a sign that his genius could not be entirely ignored. Yet the entries are cautious, even restrained. They acknowledge his poetic brilliance but also allude to his lack of discipline and to the political indiscretions that led to his downfall.

After the immediate turbulence of the rebellion passed, the court had reasons to both celebrate and distance itself from him. On the one hand, he was part of the glittering high Tang culture that later rulers wanted to claim as their heritage. On the other, he had stood a little too close to rebels and disgraced princes. The safest course was to fix him firmly in the realm of “poetry immortal” and to leave his political missteps in relative obscurity.

Over centuries, this selective memory solidified. He appears in anthologies and temple inscriptions as an almost otherworldly figure, his wine cup and moonlight verses emphasized, his brushes with treason softened or omitted. The death of poet Li Po was thereby depoliticized in later public narratives, turned from the quiet end of a nearly executed exile into the serene passing of a divinely talented stranger to mundane concerns.

This transformation reveals as much about the dynasties that followed as it does about him. Whenever a later court celebrated the arts while fearing dissent, Li Po could be invoked as a safe, distant icon: brilliant yet long dead, a model of lyrical power without uncomfortable demands for justice in the present. His political complexity was, in effect, drowned—if not in the actual river, then in the flood of a curated cultural memory.

The Human Cost: Exile, Disillusion, and the Weight of a Life’s Work

Behind the lacquer of legend lies a deeply human story: that of a man who experienced triumph and humiliation, who loved the open road but also longed for stability, and who outlived many of his dreams. If we walk alongside him in thought in his final decade, we see a figure both proud and tired, still capable of sudden joy but increasingly haunted by absence.

Exile in Tang China was not merely a change of address; it was a moral and social exile, a formal declaration that one’s relationship with the state had been damaged, perhaps beyond repair. For Li Po, the sentence to faraway Yelang—a remote and reputedly barbarous region in today’s Guizhou—was a symbolic pushing to the margins of the empire. Although a pardon halted his journey before he reached that distant posting, the psychological blow remained. He had been measured by the state and found wanting.

After the pardon, he did not simply “bounce back” into his earlier carefree persona. The poems of his later years, where authentic, often open onto emptier landscapes and lonelier drinking sessions. Friends are dead, scattered, or too embroiled in their own struggles to gather as before. The radiant comradeship of youth thinned out, replaced by memories and visions. His work’s beauty remained, but the-world-within-it darkened at the edges.

This erosion of his social world must have weighed heavily as he felt his body weakening. To have created so much, to have touched the imperial court and remote rivers alike, and yet to die in a small town, largely outside the state’s notice—there is a tragedy of scale here that makes the death of poet Li Po feel disproportionate to the life that preceded it. And yet that disproportion is, in its way, universal: few lives end on a stage as grand as their highest moments might suggest.

We can imagine him, in Dangtu or along the route there, reading over older poems or reciting them aloud to himself. Did he regret his impulsiveness at court? Did he envy those who, having taken the examinations, held steady posts even in uncertain times? Or did he consider those compromises worse than his exile, preferring to “lose” politically rather than betray the freedom that had animated his verse? The documents are silent; only the texture of his poems gives us hints, and even those must be read cautiously. What is clear is that by 762, his body and his age conspired to dictate the end of a long wandering.

From Riverbank to Legend: How the Story of His Death Took Shape

Legends rarely spring up fully formed. The story of the death of poet Li Po by drowning in the moon’s reflection likely grew in stages, as anecdotes were retold, embellished, and adapted to literary needs. To trace this growth, we have to look at how medieval Chinese readers encountered his life.

Early short biographies circulated among scholars, often attached to collections of his poems. These “small histories” were fluid; scribes copied them, teachers added details, local gazetteers inserted regional pride or gossip. A minor detail—such as his fondness for traveling by boat, or a reference to “ending his days by the river”—could gradually be magnified. A passing line in a later anthology notes that he loved to drink under the moon while at the water’s edge. In the imagination, this habit becomes a habitus: if that is how he lived, surely that must be how he died.

Poets from subsequent centuries also had strong incentives to dramatize his end. To write an elegy for Li Po was to place oneself in dialogue with a giant; the more vivid the scene, the more powerful the poem. A drowning in moonlight offered a ready-made image, amplifying themes already present in his work. Some writers may have known that the story was dubious, yet accepted it as “poetic fact,” a truth of symbol rather than archive.

As woodblock printing spread, popular illustrated books fixed the image even further. A single woodcut of a robed figure leaning from a skiff could do more to lodge the narrative in collective memory than any number of sober historical footnotes. Schoolroom recitations of his wine and moon poems, paired with these images, created generations of readers for whom the death of poet Li Po by drowning felt as inevitable as the fall of a tragic hero in a play.

By the time critical historians in the late imperial and modern eras challenged the drowning story, it was already deeply woven into cultural consciousness. Their corrections did not erase the legend; they merely added a parallel track. Today, one can visit tourist sites that commemorate the moon-drowning even as academic articles point to illness in Dangtu. The two narratives coexist, each meeting different needs: one aesthetic and emotional, the other evidentiary and analytical.

Across Dynasties: How Later Eras Reimagined Li Po’s Final Night

Every dynasty after the Tang reread Li Po in its own light. In the Song dynasty, which prized subtlety and introspective lyricism, scholars admired his technical skill but sometimes regarded his unrestrained persona with a wary curiosity. Song critics often contrasted him with Du Fu, praising the latter’s moral seriousness. Yet even they could not resist the allure of stories about the death of poet Li Po as a kind of cosmic joke played by the universe on its own favorite son.

Yuan and Ming dramatists adapted his life for the theater, embellishing encounters, adding fictional dialogues with emperors and immortals. In these plays, his death became the final act in a long moral arc. Sometimes he dies as a martyr to poetic freedom; sometimes the drowning is framed as a half-accidental, half-intentional ascent to another plane of being. The audience knew, even as they cried or laughed, that they were not watching strict history; they were watching an argument about how a poet ought to live and die.

Under the Qing, with its Manchu rulers presiding over a vast Han Chinese scholarly bureaucracy, Li Po’s political missteps were downplayed in favor of his contributions to the “national literary treasury.” Emperors themselves wrote prefaces to anthologies that included his works. His supposed manner of death was often treated as charming anecdote rather than theological doctrine, but it continued to appear, in paintings and essays, as an emblem of a life lived beyond convention.

In each era, the death-and-legend of Li Po became a mirror. Song literati saw in him a warning about excess; Ming rebels could see in him a fellow spirit unwilling to bow fully to power; Qing classicists saw an antique brilliance that justified their own claims to cultural guardianship. The details of how exactly he died in 762 became less important than what his imagined last gestures said about courage, folly, and the relationship between art and mortality.

Thus, by the time modern historians began to reassemble the sparse records, they were dealing not with a blank slate, but with a palimpsest covered in centuries of interpretive ink. Peeling back those layers does not simply reveal a “true” Li Po; it shows us how Chinese civilization, over a millennium, wrestled with questions of individuality, loyalty, and the meaning of a life defined by words.

Beyond China: The Global Afterlife of a Tang Poet

The story of the death of poet Li Po did not remain confined to China. As his poems traveled eastward to Japan and, much later, westward to Europe and the Americas, the legend of his moon-drowning often traveled with them, sometimes detached from its deeper historical context and remade in foreign imaginations.

In Japan, where Tang culture exerted immense influence, Li Po (known as Ri Haku) became part of the classical canon. Japanese poets of the Heian and later periods read him as a model of elegant intoxication, a figure whose sensitivity to nature and loneliness resonated with their own aesthetics. The anecdote of his death, while known, did not carry the same weight as his actual verses; it was one more poetic flourish in an already luminous career.

In the 19th century, Western sinologists and poets discovered him through translations. Some, like the French writer Judith Gautier and the English poet-translator Ezra Pound, were captivated by his imagery. Pound’s famous renditions in “Cathay,” based on notes by Ernest Fenollosa, brought versions of Li Po’s poems into modernist English. In these texts, the mythic contours of his life—drunken wanderings, friendships with the moon, and yes, the romantic notion of a death by drowning—fed into Western stereotypes of the “Oriental sage,” free from bourgeois constraints.

The German poet Hans Bethge, whose adaptations of Chinese poetry inspired Gustav Mahler’s “Das Lied von der Erde” (“The Song of the Earth”), also drew on Li Po. Through music and poetry, his voice was refracted into completely new artistic forms. In such settings, the historical question of whether he died of illness in Dangtu or in a river became almost irrelevant. What mattered was the image of a man who seemed to live forever in a twilight of mountains, wine, and stars.

Yet in academic circles, particularly in the 20th and 21st centuries, a more critical approach emerged. Scholars contextualized his work within Tang society, corrected mistranslations, and emphasized the political dimensions of his life and death. The death of poet Li Po thus became, for global readers, both an inviting legend and a case study in how literature crosses cultures—gaining and losing nuances with each translation, each retelling.

Memory in Stone and Ink: Shrines, Anthologies, and Schoolroom Recitations

Centuries after his death, Li Po’s presence in China remained palpable in concrete forms: temple shrines, engraved steles, and the countless printed pages of anthologies bearing his name. Towns associated with his life and with the death of poet Li Po—especially Dangtu—developed local cults of memory. Visitors could stand by rivers or in small pavilions and read lines said to have been written by him nearby, even when the historical connection was tenuous at best.

These sites were not simply tourist attractions; they were stages on which each generation reenacted its relationship with the past. Scholars traveling for examinations might stop to pay homage, offering a poem in exchange for inspiration. Local officials commissioned inscriptions praising his talent, subtly aligning themselves with his cultural prestige. Families brought children there to memorize his verses, folding his words into their own educational journeys.

Printed anthologies, from the Song onward, ensured that his works remained central to the curriculum. The “Three Hundred Tang Poems,” a famous collection widely memorized by schoolchildren into the 20th century, features multiple poems by Li Po. Many Chinese people can still recite his lines about moonlight on the bed, mistaken at first for frost, or of the desire to raise a cup and ask the bright moon to drink with him. Through such recitations, the gap of more than a thousand years compresses into a single breath.

The shrines and texts together create a double monument: stone for the body, ink for the voice. At some memorial sites, inscriptions allude directly to his death, describing it in either sober or romantic terms. One stele might speak plainly of his passing in Dangtu; another might allude to the river legend with gentle ambiguity. Visitors find themselves moving between these accounts much as historians move between chronicle and myth.

In modern China, his image has also entered mass culture: posters, television dramas, novels, even commercial branding. A wine, for instance, branded with his name or face, implicitly invites the buyer to join the poet’s eternal banquet. In these contexts, the circumstances of his death matter less than the larger-than-life persona he has come to embody. Yet in quieter corners—libraries, university departments, and modest local museums—the questions about that death remain active, part of an ongoing effort to keep his humanity visible beneath the layers of adoration.

The Poet and the Moon: Themes of Mortality in Li Po’s Work

To understand why the death of poet Li Po has been so powerfully imagined through the lens of the moon, we must return to his own poems. The moon appears not as a simple decorative element, but as a companion, a witness, and sometimes an accomplice to his solitude. In “Quiet Night Thoughts,” perhaps his most famous short poem, he looks at the moonlight on his bed, mistakes it for frost, and feels a sudden, piercing homesickness. In other poems, he toasts the moon, calls it his friend in drinking, or imagines it following him through mountain passes.

These recurring images express a complex relationship to mortality. The moon is cyclical, waxing and waning, yet to human eyes it often seems eternal, outlasting our anxieties and triumphs alike. To drink with the moon is to seek companionship with something that does not die, to set one’s brief life against the background of an enduring sky. In this sense, his wine poems are not merely celebrations of intoxication; they are meditations on how to live with the knowledge of inevitable loss.

Consider a line often attributed to him in translation: “Heaven has made me; I must have a purpose.” This assertion of meaningful existence stands beside another mood in his work, where he laments the brevity of life and the futility of worldly office. The tension between confidence and melancholy, between a sense of destiny and awareness of transience, pulses through his oeuvre. It is this tension that gives the legend of his moon-drowning its strange plausibility: it dramatizes, in one symbolic gesture, the lifelong dance between aspiration and limit.

His late poems, to the extent we can reliably date them, tilt more toward resignation. There are fewer fantasies of literal immortality, more of spiritual persistence—through friendship, through nature, and especially through writing. In one poem, he imagines his words as a boat that will continue drifting long after he is gone, carrying his voice to shores he will never see. That boat is, perhaps, the real vessel in which the death of poet Li Po can be said to have occurred: the fragile craft of language, always at risk of sinking, yet somehow afloat across centuries.

It is no coincidence that so many later readers, confronted with these themes, felt compelled to bring his life’s imagery full circle in their telling of his death. To say he drowned reaching for the moon is to compress a lifetime of metaphors into a single symbol, to make visible in a moment what his poems explored across dozens of pages. Whether or not that is how he physically died, it remains a hauntingly accurate portrait of how he lived—always reaching beyond the immediate surface of things for a reflection of something higher, knowing it could never truly be grasped.

History, Myth, and Evidence: Reconstructing the Death of Poet Li Po

We arrive, at last, at the crossroads of fact and fiction. On one path stands the austere historian, armed with the “Old Book of Tang,” the “New Book of Tang,” local gazetteers from Anhui, and philological analyses by modern scholars. On the other path stands the storyteller, cradling paintings, plays, rumors, and the glowing image of a boat under the moon. The death of poet Li Po lies somewhere between these paths, in a clearing we can approach but never entirely occupy.

From the evidentiary side, the case is fairly clear. He died around 762, in or near Dangtu, probably of illness related to age and physical strain. No near-contemporary source records a drowning while drunk on the river. Later documents that do mention such a scene are demonstrably shaped by literary convention and were written long after anyone with first-hand knowledge had passed away. As one modern scholar succinctly put it in a journal article on Tang biographical traditions, “The moon-drowning of Li Bai is history only in the history of reception.”

From the mythic side, however, the drowning story carries a different kind of truth. It reflects how readers over centuries interpreted his work and his persona. It acknowledges his lifelong embrace of risk, spontaneity, and intoxication. It sings, in a single emblem, of the unity between his inner world and the natural cosmos that he so often evoked. To discard the legend entirely would be to ignore a major chapter in the biography of his reputation, even if we must mark that chapter clearly as imaginative.

The honest reconstruction, then, requires us to speak in layers. We can say, with confidence grounded in documents, that the death of poet Li Po was likely quiet and human: an old man in pain, his range of motion shrinking, his mind perhaps still racing with images he no longer had the strength to set down. We can also say, with equal confidence but different emphasis, that for much of Chinese history he has been remembered as if he rose from that bed, stepped into a boat, and chose to vanish into the very imagery that had defined him.

In one sense, both stories are tragedies. In another, both are victories. The first affirms our shared vulnerability; the second affirms the capacity of art to make even an ending luminous. Between them, we find a richer understanding: that the true afterlife of Li Po lies not in how he physically died, but in how his living words continue to ripple outward, catching new reflections of the moon in every language that dares to translate him.

Conclusion

The man who once wrote that he would “ride the wind and break the waves” ended his days in a world he could not control: a shattered empire, a frail body, a reputation both cherished and compromised. The death of poet Li Po in 762 was, as far as the records tell us, the passing of a sick, aging wanderer in a modest place. Yet the story does not end there, because his poems refused to die with him. They survived burning cities, dynastic changes, and even the distortions of their own success.

Across more than a thousand years, readers have returned to him not simply to be charmed by moonlight and wine, but to confront, in his lines, the tension between longing and limit that shapes all human lives. The myth that he drowned embracing the moon is, in this light, less a lie than a kind of collective dream, an image through which later generations expressed their desire to see a life of such rare unity between word and world sealed with a fitting final scene. The historian’s task has been to gently separate that dream from the sparse documentary core, to honor both the actual man and the imaginative edifice built around him.

In doing so, we see more clearly what 762 signifies: not only the end of one poet’s journey, but a turning point in the history of the Tang dynasty, and in the cultural memory of what it means to be an artist under power. The death of poet Li Po reminds us that genius offers no protection from exile or illness, but it does offer a kind of second life in language—one that can outlast even the most glamorous or tragic of endings. Today, whether we picture him in a quiet room in Dangtu or in a tilting boat under a silver sky, we are still, in some sense, his contemporaries, sharing in a moment of looking up at the same moon he once addressed. And as long as that act of shared looking continues, his final departure will remain, paradoxically, unfinished.

FAQs

- Did Li Po really die by drowning while reaching for the moon?

Most modern historians believe he did not. Early authoritative sources suggest he died of illness in Dangtu in 762, and the famous drowning legend appears only in later, more literary accounts. The story survives because it beautifully matches the imagery of his poems, but it should be treated as myth rather than documented fact. - Where did the death of poet Li Po actually occur?

According to traditional records and local memorials, Li Po died in Dangtu County, in present-day Anhui province, after receiving a partial pardon from an earlier exile sentence. His tomb and several commemorative sites in that region attest to this long-standing association. - How did the An Lushan Rebellion influence his fate?

The rebellion destabilized the Tang empire and entangled Li Po in dangerous political currents. His association with the Prince of Yong led to charges of complicity in rebellion, a death sentence that was later commuted to exile. The turmoil of these years pushed him away from the court for good and set him on the path that ended with his death in 762. - What role did wine and intoxication play in his life and death?

Wine was central to Li Po’s persona and poetry; he often portrayed drinking as a way to transcend worldly worries and commune with nature and the moon. While heavy drinking may have contributed to his declining health, there is no firm evidence that it directly caused his death. The image of a drunken drowning is more symbolic than historical. - How did his contemporaries react to his death?

Contemporaries such as Du Fu wrote moving elegies for Li Po, portraying him as a fallen immortal and lamenting the loss of his genius in a time of war and suffering. Their poems serve as some of the earliest and most personal records of how his passing was felt among the educated elite of his day. - Why does the legend of his moon-drowning remain so popular?

The legend survives because it distills the essence of his poetic world: rivers, night skies, intoxication, and a yearning for transcendence. It provides a dramatic, memorable image that teachers, artists, and storytellers can easily pass on, even when they acknowledge that it is not historically accurate. - How is Li Po remembered in China today?

Li Po is celebrated as one of the greatest poets in Chinese history, often paired with Du Fu as a twin pinnacle of Tang verse. His poems are taught in schools, his image appears at cultural sites and in popular media, and places linked to his life and death, especially Dangtu, continue to attract visitors seeking a connection with his legacy. - What is the best way to start reading Li Po’s work?

A good starting point is a reliable bilingual edition of his poems, ideally with scholarly notes that explain historical and cultural references. Anthologies of Tang poetry that include his most famous pieces—such as “Quiet Night Thoughts” and his wine and moon poems—allow new readers to encounter both his lyrical intimacy and his grand, expansive vision.

External Resource

Internal Link

Other Resources

- Encyclopaedia Britannica – general search for the exact subject

- Google Scholar – academic search for the exact subject

- Internet Archive – digital library search for the exact subject