Table of Contents

- The Dawn of Al-Andalus: A Land of Conquest and Promise

- The Flight of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I: From Umayyad Prince to Exile

- A New Beginning in the Iberian Peninsula

- The Fragmented Landscape of the Iberian Peninsula in the Mid-8th Century

- The Political and Religious Tensions Behind the Emirate’s Birth

- Crossing the Straits: The Strategic Journey to Al-Andalus

- The Early Struggles to Establish Authority

- The Battle of Musarah: A Defining Moment of Power

- The Consolidation of Córdoba: From Fortress to Capital

- Administrative Innovations and Tribal Politics

- ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s Relationship with the Berbers and Arabs

- The Role of the Mozarabs and Urban Communities

- Religious Policy: Tolerance, Islamic Orthodoxy, and Political Strategy

- Architectural Flourishes and the Birth of a New Cultural Identity

- The Emirate’s Economy: Agricultural Innovation and Trade Networks

- Rivalries and Rebellions: Challenges to ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s Rule

- External Threats and Diplomacy: Frankish Kingdoms and Abbasids

- The Emir’s Legacy: Laying the Foundation for the Caliphate of Córdoba

- The Human Stories Behind the Founding of a Dynasty

- The Lasting Global Impact of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I’s Rule

- Conclusion: The Genesis of a Golden Age in Iberia

- Frequently Asked Questions

- External Resource: Wikipedia Link

- Internal Link: Visit History Sphere

The year was 756 CE. The sun blazed fiercely over the fragmented hills of the Iberian Peninsula. At that very moment, a man arrived—an exile, a scion of a fallen dynasty, but above all a survivor. From the ashes of the Umayyad Caliphate’s downfall in Damascus, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I landed on the rebellious shores of al-Andalus, ready to carve out a haven amid chaos. The air buzzed with tension; a mosaic of Christian kingdoms, Muslim factions, and local tribes made the land simultaneously a theater of war and a cradle for burgeoning culture. Little did anyone then realize that this fugitive prince would soon consolidate power, creating an emirate whose heartbeat would echo for centuries.

1. The Dawn of Al-Andalus: A Land of Conquest and Promise

Al-Andalus—what a name rings out like a promise and a mystery. Once the westernmost province of the mighty Umayyad Caliphate, this region had become a patchwork quilt of alliances and fracturing loyalties. The early Muslim conquests had swept through the Iberian Peninsula less than two decades before, but by the mid-8th century, the initial unity was fading fast. These were lands of fertile valleys, bustling ports and fiercely independent peoples, both Muslim and Christian, who eyed each other with caution.

The arrival of Muslim armies in 711 had opened the door for cultural and scientific flourishing, but also for deep political fractures. By 750, the central authority of the Umayyad dynasty was shattered in the East, swept away by the rising Abbasid Caliphate, whose ideology opposed the very bloodline to which ʿAbd al-Raḥmān belonged. Thus, the west—al-Andalus—became the lonely refuge for an Umayyad fugitive intent on survival, vengeance, and destiny.

2. The Flight of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I: From Umayyad Prince to Exile

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Muʿāwiya ibn Hishām was no ordinary man. He was the grandson of Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, one of the last great Umayyad caliphs, raised amidst the marble halls and intrigues of Damascus. But after the Abbasid Revolution erupted in 750, the Umayyads were hunted like game. Men, women, and children were slaughtered or scattered. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s escape was one of the great dramas of the age—fleeing through deserts, mountains, and hostile lands, executing murders and betrayals with nerves of steel, only to find himself shipbound across the Mediterranean.

Arriving in al-Andalus, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān was a fugitive prince without an army, a claim, or even a clear plan. Yet, his determination to restore Umayyad power ignited his drive to build more than just refuge; he sought empire.

3. A New Beginning in the Iberian Peninsula

Upon arrival, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān encountered a land rife with conflict. Muslim forces, mostly Berbers who had initially conquered Iberia, were divided among rival factions. The local Christian nobles watched with suspicion the arrival of an Arab prince who might upset their fragile autonomy. Moreover, the Abbasids, seated in distant Baghdad, pressed to bring the West under their control.

With charisma, military acumen, and the blessing of some local Arab and Berber groups wary of Abbasid domination, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān began a campaign both political and martial. He understood the importance of forging alliances while decisively crushing opposition. His story was no longer just about survival: it was a careful process of statecraft.

4. The Fragmented Landscape of the Iberian Peninsula in the Mid-8th Century

To understand the emirate’s foundation, one must see the Iberian Peninsula as it was then—a patchwork of small Christian kingdoms in the north such as Asturias, territories dominated by Berber military settlers, Arab elites, remaining Visigothic nobles converted or under pressure, and a large population of Mozarabs—Christians living under Muslim rule.

This mosaic was volatile. Tribal loyalties ran deep, religious identities were complex, and the land's rugged geography favored localized power centers. Without a unifying figure, al-Andalus risked permanent fragmentation—exactly the vacuum ʿAbd al-Raḥmān aimed to fill.

5. The Political and Religious Tensions Behind the Emirate’s Birth

The political scene was loaded with grievances and ambitions. The Abbasids’ rise in the East meant shifting ideological sands. The Umayyads had been Arab-centric and more lax in religious enforcement; the Abbasids claimed a religious legitimacy that emphasized Shia sympathies and Persian influence. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s challenge was to maintain religious legitimacy in a Sunni context while asserting his own dynastic claims far from the supportive old power base.

Moreover, the Berbers, essential military players, posed a challenge. While many had helped conquer Iberia, they felt marginalized by Arab dominance, leading to several rebellions. Additionally, Christians in al-Andalus lived under dhimmi status, a complex condition blending tolerance and restrictions.

6. Crossing the Straits: The Strategic Journey to Al-Andalus

The crossing of the Strait of Gibraltar was no small feat. This narrow waterway symbolized the division between two worlds: the Arab heartlands and the European frontier. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s arrival was both a literal and symbolic crossing of thresholds. According to chroniclers, his fleet was small, his men loyal but few, yet their bravery and unity belied their numbers.

This crossing also signaled a turning point: here, an Umayyad flame refused to die and would instead light a new empire. The story of crossing the straits remains a vivid metaphor for endurance and ambition in Islamic and European history alike.

7. The Early Struggles to Establish Authority

Once ashore, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān had to face entrenched forces. The Berbers controlled large swaths of the land; rival Arab factions claimed status and privilege; Christian lords watched carefully for any opportunity. Many local governors were skeptical or outright hostile. Initial victories were far from guaranteed.

Yet, leveraging tribal rivalries, promising rewards to loyalists, and demonstrating military prowess, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān began the steady process of consolidating his rule. He was pragmatic—willing to negotiate, to fight, and to punish with equal firmness.

8. The Battle of Musarah: A Defining Moment of Power

It was at the Battle of Musarah in 763 that ʿAbd al-Raḥmān struck what many historians call the decisive blow in uniting al-Andalus under his banner. Facing a coalition of Berber tribes and rival Arab chiefs, his smaller but disciplined forces routed their opponents.

This victory was more than military; it shattered the opposition’s will and established ʿAbd al-Raḥmān as the uncontested leader of the emirate. The battle’s memory became a symbol of unity against internal divisions—a cornerstone for the new state.

9. The Consolidation of Córdoba: From Fortress to Capital

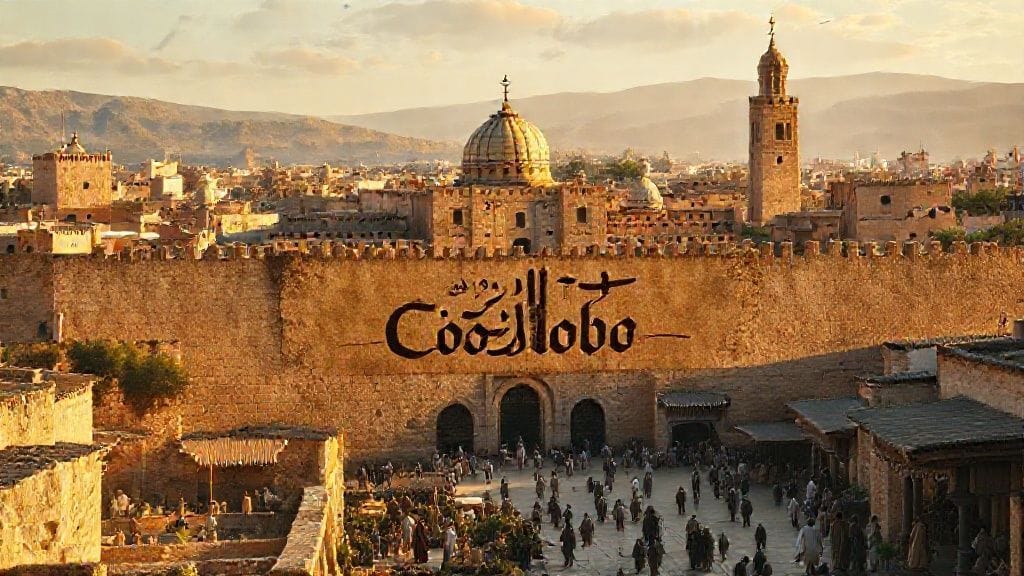

Córdoba, once a modest Roman town turned Visigothic outpost, took on new life under ʿAbd al-Raḥmān. Choosing it as his capital was both strategic and symbolic: centrally located, defensible, and ripe for transformation.

Under his rule, Córdoba was fortified and expanded, developing into a vibrant center of administration, culture, and religion. The city walls rose, palaces and mosques began to dot the landscape, social institutions blossomed, and a new urban elite emerged. Córdoba was no longer a frontier outpost—it was a beacon of power.

10. Administrative Innovations and Tribal Politics

Consolidating power involved more than battles; ʿAbd al-Raḥmān introduced administrative reforms to manage diverse populations. He established complex tax systems, appointed trusted governors, and balanced tribal interests to prevent any single group from growing too powerful.

He cleverly integrated Arab, Berber, and local forces into a governing system that could sustain his authority, fostering a nascent state apparatus. His reign marks the beginning of systematic governance in al-Andalus.

11. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s Relationship with the Berbers and Arabs

The dynamics between Arabs and Berbers were thorny. Many Berbers, initially allies, felt discriminated against in the emirate’s hierarchy—resentments that occasionally sparked revolts. Yet, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān understood his long-term viability depended on their support.

Rather than outright exclusion, he incorporated Berber leaders carefully, sometimes granting autonomy in exchange for loyalty. This balancing act was precarious but foundational, allowing divided ethnic groups to coexist under his firm leadership.

12. The Role of the Mozarabs and Urban Communities

Christian communities under Muslim rule, known as Mozarabs, played a subtle but vital role in the emirate’s society. Though subjects, they maintained religious practices and contributed economically and culturally.

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s comparatively tolerant policy allowed Mozarabs to thrive in certain urban centers, acting as intermediaries between Muslim rulers and Christian lands to the north. This coexistence enriched Al-Andalus’ cultural mosaic and contributed to its later intellectual flowering.

13. Religious Policy: Tolerance, Islamic Orthodoxy, and Political Strategy

Balancing Islamic theology with political pragmatism was key. While ʿAbd al-Raḥmān promoted Sunni Islam as a unifying identity, he also tolerated Christians and Jews, recognizing their roles in society.

This religious policy was neither purely tolerant nor harsh but a calculated strategy to maintain peace and stability. By avoiding deep sectarian conflict, he paved the way for Al-Andalus to become a center of religious coexistence—at least relative to Europe at the time.

14. Architectural Flourishes and the Birth of a New Cultural Identity

Under his reign, cordoba saw the first seeds of architectural grandeur, foreshadowing a later golden age. New mosques, palaces, and public baths punctuated the cityscape, mixing Roman, Visigothic, and Islamic influences.

This building campaign wasn’t just practical; it set the tone for the emirate’s identity, blending diverse heritages into a unique Andalusian cultural expression. The Great Mosque of Córdoba, later expanded by his successors, began as a symbol of Umayyad resilience and ambition under his patronage.

15. The Emirate’s Economy: Agricultural Innovation and Trade Networks

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I boosted the emirate’s economy by encouraging agriculture—introducing irrigation techniques and new crops such as rice, citrus, and sugar cane. The fertile Guadalquivir valley became a breadbasket supplying urban centers.

Trade, both Mediterranean and trans-Saharan, flourished under his governance. Córdoba became a hub connecting Europe, North Africa, and the Near East, attracting merchants and artisans. This economic vitality solidified the emirate’s foundations beyond mere military conquest.

16. Rivalries and Rebellions: Challenges to ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s Rule

The story was not of unbroken triumph. Rebellions erupted periodically, especially among disaffected Berbers and local chieftains. Some Arab factions opposed his rule; others plotted with Christian kingdoms to undermine the emirate.

However, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s combination of military decisiveness and political diplomacy enabled him to quash or co-opt these threats. His reign was defined by a dynamic tension—ruling over a land still in flux but moving steadily towards unity.

17. External Threats and Diplomacy: Frankish Kingdoms and Abbasids

Beyond internal struggles, external powers eyed al-Andalus with concern or opportunity. The rising Carolingians in the Frankish north challenged Muslim expansion, culminating later in battles like Poitiers.

Meanwhile, the Abbasids sought to erode Umayyad legitimacy and possibly incorporate al-Andalus. Yet ʿAbd al-Raḥmān skillfully navigated these threats, maintaining independence through diplomatic tact, military readiness, and symbolic gestures such as refusing Abbasid recognition but avoiding outright war.

18. The Emir’s Legacy: Laying the Foundation for the Caliphate of Córdoba

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s reign was more than survival; he fashioned an enduring political entity. His establishment of the emirate and consolidation of power prepared the ground for his successors to declare Córdoba a caliphate in 929, crowning al-Andalus as a political and cultural powerhouse.

The foundation he laid enabled a blossoming of arts, science, and philosophy, making Córdoba a jewel of medieval civilization.

19. The Human Stories Behind the Founding of a Dynasty

Beyond battlefields and palaces, countless personal stories shimmer. The loyalty of his closest companions, the betrayals endured, the hopes of refugees warmly embraced or crushed – these human elements enriched ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s narrative.

His wife, children, advisors, and enemies all shaped the emir’s complex portrait: a man haunted by exile yet animated by a fierce will to create a home and legacy.

20. The Lasting Global Impact of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I’s Rule

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I’s emirate was not a mere regional curiosity. By establishing a flourishing Muslim polity in the heart of Europe, he catalyzed centuries of cultural exchange among Islamic, Christian, and Jewish worlds.

This cross-pollination influenced art, science, philosophy, and governance across continents. The echoes of al-Andalus resonate in Mediterranean history, illustrating how exile and ambition reshaped civilizations.

Conclusion

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I’s story is a compelling human drama—a prince on the run who transformed exile into empire. His consolidation of the Emirate of Córdoba was not simply a political maneuver; it was an act of extraordinary resilience, vision, and synthesis. Against odds, he stitched together fractious peoples and rival factions into a durable state, planting seeds that would bloom into one of medieval Europe's most dazzling cultural achievements.

What makes this history enduring is its reminder that identity, power, and culture are forged amid adversity and negotiation, not just conquest. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s emirate was a beacon in the twilight of old empires and the dawn of new worlds—a testament to the indomitable spirit of survival and state-building.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Who was ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I, and why was he significant?

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I was the Umayyad prince who fled the Abbasid massacre in Damascus and founded the Emirate of Córdoba in al-Andalus. His significance lies in establishing a stable Muslim polity in Iberia, setting the stage for centuries of cultural and political influence.

Q2: What challenges did ʿAbd al-Raḥmān face upon arriving in al-Andalus?

He encountered a fragmented region divided by tribal, ethnic, and religious tensions, opposition from Berber and Arab factions, and external threats from Christian kingdoms and the Abbasid Caliphate.

Q3: How did ʿAbd al-Raḥmān manage relations between Arabs and Berbers?

He balanced power by incorporating Berber leaders, sometimes granting autonomy, while maintaining Arab political dominance. This pragmatic approach helped keep peace amid competing interests.

Q4: What role did Córdoba play in the emirate?

Córdoba was the political and cultural capital, transformed from a frontier town into a thriving metropolis and symbol of Umayyad presence and identity.

Q5: How did ʿAbd al-Raḥmān’s rule influence later Islamic Spain?

His consolidation laid the groundwork for the Caliphate of Córdoba, which became a center for intellectual, cultural, and scientific achievements during the medieval period.

Q6: Was religious tolerance practiced under ʿAbd al-Raḥmān?

While Islamic orthodoxy was promoted, Christians and Jews were generally tolerated under dhimmi status, allowing a multi-religious society albeit within a hierarchical framework.

Q7: What external powers influenced or threatened the emirate?

The Abbasid Caliphate in the East sought to control the region, and Christian kingdoms, notably the Franks, posed military challenges. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān navigated these with diplomacy and military strength.

Q8: What is the lasting legacy of the Emirate of Córdoba under ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I?

His reign symbolizes the resilience of a dynasty and a culture that bridged East and West, laying foundations for intellectual and artistic flourishing that influenced Europe and the Islamic world.