Table of Contents

- The Dawn of an Architectural Marvel: Córdoba in the Late 8th Century

- Córdoba under the Umayyad Emirate: A City at the Crossroads

- Abd al-Rahman I: The Refugee Prince and Founder of the Emirate

- Religious Landscapes in al-Andalus Before the Mosque

- The Decision to Build: Patronage and Power Intertwined

- Foundations Laid: The First Stones of the Great Mosque (785–786)

- Architectural Vision: Fusion of Traditions and Innovation

- Building the Mosque: Labor, Materials, and Techniques

- The Mosque as Symbol: Politics, Religion, and Identity

- Life Around the Mosque: Córdoba’s Urban and Social Fabric

- The Mosque’s Early Reception: Awe and Controversy

- The Great Mosque as a State Instrument: Patronage Begins

- Expansion and Renovations: Seeds Planted in the First Decade

- Artisans and Architects: The Creators Behind the Masterpiece

- The Great Mosque’s Role in the Umayyad Emirate’s Consolidation

- The Religious Landscape Transformed: From Church to Mosque

- Symbolism Embedded in Stone: The Mosque and Territorial Claims

- The Mosque’s Legacy in Islamic and European History

- The Memory of the Great Mosque in Later Centuries

- Conclusion: A Monument Beyond Time and Faith

- FAQs: Exploring the Great Mosque of Córdoba

- External Resource

- Internal Link

The Dawn of an Architectural Marvel: Córdoba in the Late 8th Century

It was a time when the twilight of old empires met the dawn of new regimes. The year 785 saw Córdoba, a vibrant city nestled on the banks of the Guadalquivir River, brace itself for a creation that would forever alter its skyline and soul. The air hummed with expectancy, dust swirling like the uncertain fortunes of the Iberian Peninsula itself. As the first stones of the Great Mosque were laid, a monumental transformation began—one that blended the sacred with the sovereign, the spiritual with the political, and the earthly with the divine.

The story of the Great Mosque of Córdoba is not simply a tale of architecture; it is the story of a young emirate staking its claim on a new world, a narrative molded by exile, power, faith, and artistry. To understand why Córdoba would become the site of such a colossal project, we must first traverse the dense forest of its history, politics, and religious currents coursing through al-Andalus at the time.

Córdoba under the Umayyad Emirate: A City at the Crossroads

In the late 8th century, Córdoba was no longer just a forgotten Roman outpost or a minor Visigothic town; it was the burgeoning heart of the Umayyad Emirate in al-Andalus. More than a mere provincial capital, Córdoba had grown into an administrative and cultural hub following the establishment of Umayyad rule under Abd al-Rahman I, a scion of a fallen dynasty fleeing the Abbasid Revolution.

The city was a mosaic of peoples—Arabs, Berbers, Christians, Jews, and indigenous Iberians—all weaving their customs and beliefs into the city’s vibrant tapestry. Córdoba’s streets echoed with the sound of different tongues and prayers, but it was still a city searching for cohesion amidst its diversity.

Abd al-Rahman I: The Refugee Prince and Founder of the Emirate

Central to this epoch was Abd al-Rahman I. Escaping the massacres that had eradicated his family’s reign in Damascus, he arrived in al-Andalus in 755, carving out a fragile emirate that, while nominally under the Abbasids, was effectively independent. His reign was marked by consolidation, diplomacy, and cultural florescence, yet also by the pressing need to legitimize his rule.

Building a monumental mosque became an essential assertion—an indelible mark proclaiming the Umayyad Emirate’s permanence. It was Abd al-Rahman’s vision and patronage that set the wheels of this transformative project in motion.

Religious Landscapes in al-Andalus Before the Mosque

Before the mosque’s construction, al-Andalus bore the marks of its Christian Visigothic past, dotted with churches and basilicas. The Great Cathedral of Córdoba had once stood as a symbol of Christian power, its lands and stones bearing witness to the old regime.

The Umayyad rulers inherited a complex religious landscape: how to honor the new Islamic order without erasing the cultural substratum? The decision to construct a grand mosque on the site of a former Visigothic church would answer this question definitively—religion became the instrument of statecraft.

The Decision to Build: Patronage and Power Intertwined

The Great Mosque was not simply a place of worship; it was a statement. Abd al-Rahman’s patronage was a calculated political act designed to unify Muslims under his leadership and to present al-Andalus as a legitimate center of Islamic culture and power.

Patronage had a long tradition in Islamic governance—it was through monumental architecture that rulers asserted divine sanction and worldly dominance. The mosque was to serve as the communal heart of Córdoba, a center for prayer, education, and governance.

Foundations Laid: The First Stones of the Great Mosque (785–786)

In 785, the foundations of the Great Mosque were laid on the site of the former Christian Basilica of San Vicente. The choice was symbolic and strategic, erasing the Christian dominance and replacing it with an emblem of Islamic power. Construction began with fervor, led by skilled architects and craftsmen who blended the latest in Islamic design with local building traditions.

The mosque’s initial phase, completed around 786, was a vast rectangular space with a hypostyle hall supported by rows of horseshoe arches, evoking the visionary fusion of function and faith.

Architectural Vision: Fusion of Traditions and Innovation

The Great Mosque emerged as a bold architectural synthesis. It combined the Umayyad tradition inherited from Syria and Palestine with influences from the Visigothic and Roman heritage embedded in the land.

The innovative double-tiered arches, the use of red and white voussoirs, and the expansive courtyard all heralded a mosque unlike any other in the western Islamic world. This architectural audacity spoke of a new era—a creative dialogue between inherited knowledge and local innovation.

Building the Mosque: Labor, Materials, and Techniques

The construction demanded vast resources and skilled labor drawn from Córdoba’s diverse population. Local stone, marble recycled from Roman ruins, and timber were painstakingly gathered and shaped.

Artisans from across the Mediterranean contributed their expertise. The laborers’ sweat mixed with the prayers of the faithful, blending spiritual dedication with human toil.

The Mosque as Symbol: Politics, Religion, and Identity

The Great Mosque was a grand symbol, a visual manifesto of Umayyad legitimacy in al-Andalus. It signaled a break from the past and a claim to Islamic identity. Under Abd al-Rahman’s patronage, the mosque became a locus for political power and religious authority.

The assertion was clear: this was not a transient conquest but a definitive foundation of a new civilization.

Life Around the Mosque: Córdoba’s Urban and Social Fabric

The mosque was not an isolated monument. It stood at the city’s heart, interwoven with bustling markets, scholarly schools, homes, and political offices. It shaped urban life and social interactions, offering a space where faith and daily life coincided seamlessly.

The Great Mosque became a magnet for scholars, poets, theologians, and traders alike, making Córdoba an unparalleled Mediterranean cultural hub.

The Mosque’s Early Reception: Awe and Controversy

While many marveled at its architectural ingenuity and spiritual significance, the mosque’s construction stirred tensions. Christians saw it as a symbol of erasure, while some Muslims debated the mosque’s scale and audacity.

Yet, even its critics could not deny the growing role the mosque played in consolidating Córdoba's cultural and religious primacy.

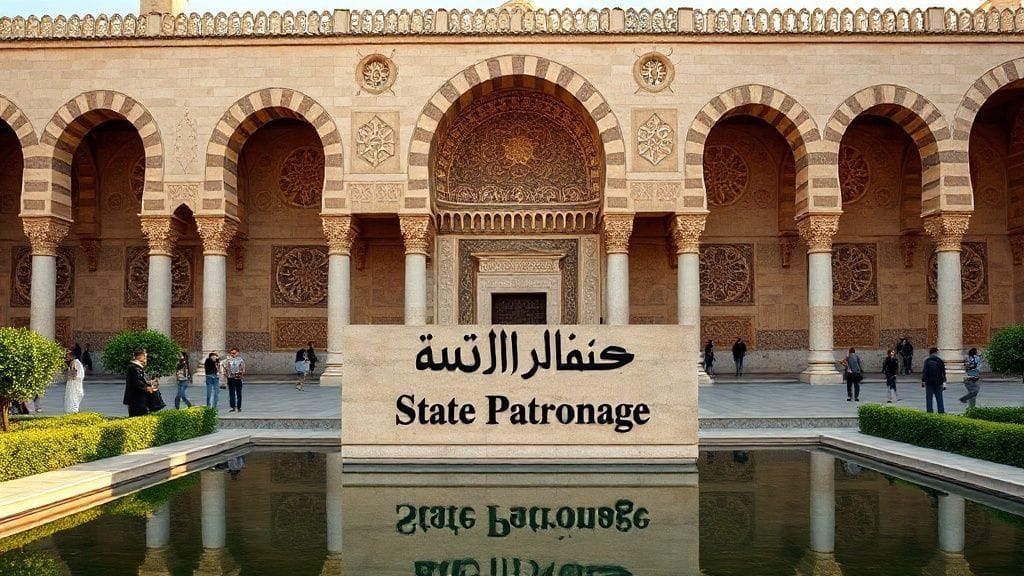

The Great Mosque as a State Instrument: Patronage Begins

From the outset, the emir’s state patronage underpinned the mosque’s construction. Abd al-Rahman’s financing, political support, and symbolic oversight ensured that the mosque was more than a religious building—it was an instrument of governance, administration, and identity.

Such patronage marked the beginning of a long tradition of rulers wielding architecture as a tool of political power in Iberia.

Expansion and Renovations: Seeds Planted in the First Decade

Though the initial construction was monumental, the mosque was a living project. Abd al-Rahman and his successors would expand and embellish the mosque throughout the following decades, enhancing its grandeur and complexity.

The seed planted in 785-786 soon sprouted into a sprawling architectural masterpiece.

Artisans and Architects: The Creators Behind the Masterpiece

The mosque’s creators remain partly anonymous, but records hint at a multiracial collective of architects, engineers, artisans, and laborers. Their legacy is embedded in the stones and arches, a testament to collaboration across cultures.

Some scholars suggest influences from the Umayyad heartlands and Byzantine traditions, while local craftsmanship added a distinctive Andalusian flavor.

The Great Mosque’s Role in the Umayyad Emirate’s Consolidation

The mosque played a crucial role in the Umayyad emirate’s political consolidation. It was the site of official prayers attended by elites, where caliphal authority was both spiritually sanctified and politically reinforced.

The mosque was a pillar of the emirate's identity, intertwining governance with faith.

The Religious Landscape Transformed: From Church to Mosque

The transformation from Christian church to Muslim mosque encapsulated the broader religious shifts in al-Andalus. The Great Mosque marked the ascendancy of Islam in the region, a visible and permanent turn.

Yet, vestiges of the old religious cultures intermingled with the new, creating a unique, layered spiritual landscape.

Symbolism Embedded in Stone: The Mosque and Territorial Claims

Every arch and column declared a message. The Great Mosque’s scale and artistic grandeur were a territorial claim—both to the land and to history. It inscribed Umayyad power into Córdoba’s very fabric, proclaiming al-Andalus as an essential part of the Islamic world.

The building was diplomacy and declaration carved in stone.

The Mosque’s Legacy in Islamic and European History

The Great Mosque of Córdoba set a precedent. Its architectural innovations influenced mosque-building across North Africa and the Maghreb, while its grandeur echoed through European imagination.

Centuries later, it would become a symbol of cultural exchange, coexistence, and sometimes, conflict—the very essence of medieval Iberia.

The Memory of the Great Mosque in Later Centuries

The mosque's fate changed with the Reconquista, becoming a cathedral after 1236. Yet, its original structure survived, a palimpsest of religious and cultural layers.

Today, it stands as a monument not just to Islam or Christianity, but to the complex history of a land where civilizations met.

Conclusion

The beginning of the Great Mosque of Córdoba’s state patronage in 785–786 was more than the erection of a building—it was the birth of a symbol, a crucible of identity, power, and faith. Abd al-Rahman I’s vision transformed the city’s skyline and its soul, heralding a civilization that would resonate through the centuries.

The mosque’s stones whisper stories of exile and empire, of artisans and rulers, of devotion and ambition. It reminds us how architecture transcends mere function, becoming a living history that continues to inspire awe and reflection.

FAQs

Q1: Why was the Great Mosque of Córdoba built on the site of a former church?

A1: Building the mosque on the site of the Visigothic Basilica was a deliberate political and religious statement, symbolizing the ascendancy of Islam and the Umayyad emirate’s legitimacy in al-Andalus.

Q2: Who was Abd al-Rahman I and why was his patronage crucial?

A2: Abd al-Rahman I was the Umayyad emir who fled Damascus and founded the emirate in al-Andalus. His patronage was crucial because he sought to legitimize his rule and unify the Muslim community through monumental architecture.

Q3: What architectural innovations characterized the mosque’s initial construction?

A3: The mosque featured innovative horseshoe arches with alternating red and white stones, a hypostyle prayer hall, and a large courtyard, blending Islamic, Roman, and Visigothic design elements.

Q4: How did the mosque reflect political power?

A4: As a state project, the mosque served as a symbol of Umayyad authority, a place of communal worship that also reinforced the political legitimacy of the emirate’s rulers.

Q5: What was the mosque’s impact on Córdoba’s social life?

A5: The mosque became a focal point for religious, political, and social activities, attracting scholars, traders, and citizens, thus shaping the urban and cultural life of Córdoba.

Q6: How did later Christian rulers treat the Great Mosque?

A6: After the Reconquista, the mosque was converted into a cathedral, but much of the original structure was preserved, making it a unique architectural palimpsest of two great religions.