Table of Contents

- The Earthquake That Shook a Nation: February 4, 1976

- Prelude to Disaster: Guatemala's Geographical and Social Landscape

- A Country on the Brink: Political and Economic Tensions in the 1970s

- The Morning of February 4: A Tremor Felt Beyond Borders

- Magnitude and Mechanics: Understanding the 7.5 Richter Scale Event

- The Epicenter’s Wrath: Chimaltenango and the Western Highlands under Siege

- Collapse and Chaos: The Immediate Aftermath in Urban and Rural Areas

- Human Stories Amid Ruins: Tales of Loss, Courage, and Survival

- The Role of the Guatemalan Government: Response and Controversies

- International Aid: Support, Solidarity, and Geopolitical Undertones

- The Role of the Military Junta: Between Assistance and Repression

- Reconstruction Efforts: The Long Road to Recovery

- Impact on Indigenous Communities: A Demographic and Cultural Catastrophe

- Economic Costs and Development Setbacks

- The 1976 Earthquake in Memory and Culture: Art, Literature, and Collective Trauma

- Advances in Seismology and Disaster Preparedness Spawned by the Tragedy

- Reflections from Survivors: Voices from the Rubble

- The Earthquake as a Catalyst for Political Change?

- Comparative Perspectives: Guatemala 1976 and Global Earthquakes

- The Legacy 40 Years On: Remembrance and Lessons Learned

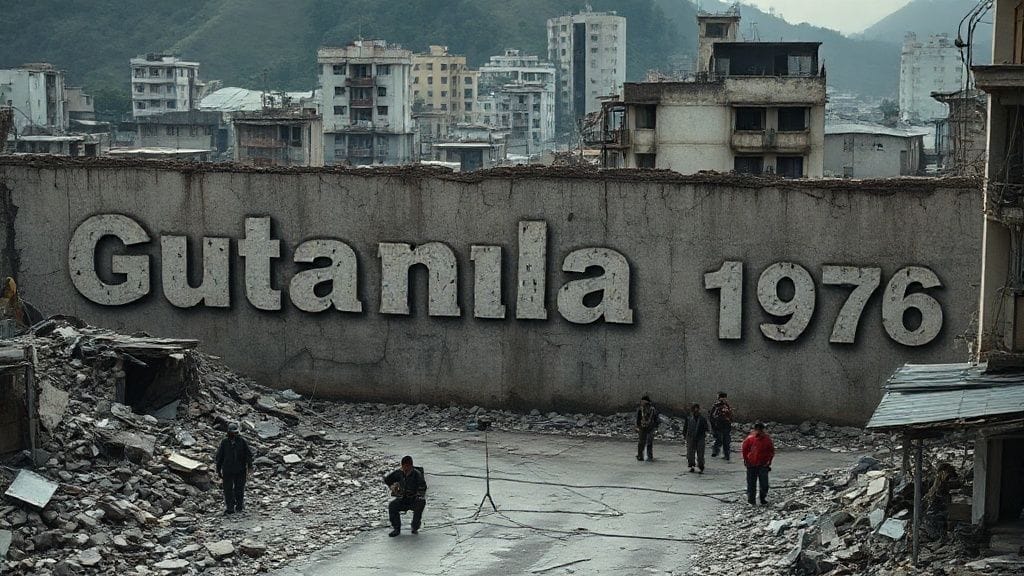

The Earthquake That Shook a Nation: February 4, 1976

As dawn broke on February 4, 1976, a sudden, violent shudder tore through the air of Guatemala. Buildings quivered, glass shattered, and the very earth seemed to convulse beneath the feet of thousands. What began as an ordinary day for millions swiftly transformed into an unimaginable nightmare. In mere seconds, the country’s western highlands—its towns, villages, and cities—lay in ruin, and with them, tens of thousands of lives were irrevocably altered. The 1976 Guatemala Earthquake was not merely a natural disaster. It was a harrowing chapter etched deeply into the national psyche, a moment when nature's fury collided with societal vulnerability, exposing fractures far beyond the geological.

That earthquake, which would register a devastating 7.5 on the Richter scale, left a swath of destruction that stretched hundreds of kilometers, sparking grief, endurance, and also political and social reckoning. To grasp the magnitude of this tragedy, one must step back in time, to understand the land, the people, and the intricate forces that shaped the catastrophe—and shaped Guatemala’s decades that followed.

Prelude to Disaster: Guatemala's Geographical and Social Landscape

Nestled between the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, Guatemala's rugged terrain is defined by volcanoes, mountains, and fertile highlands. This dynamic geological setting, part of the notorious “Ring of Fire,” predisposes the country to seismic hazards. Thousands of years of volcanic activity sculpted the dramatic landscape but also laden threats of earthquakes and eruptions. Indeed, Guatemala’s history is punctuated by seismic events; tectonic plates crawl beneath its surface, simmering with potential energy.

But geology alone does not explain why the 1976 earthquake’s consequences were so profound. Guatemala’s social fabric, tightly knit yet deeply frayed, played an equally critical role. The country was home to a diverse population, including indigenous Maya groups who inhabited rural highlands and marginalized communities often living in poverty and with limited access to infrastructure. Urban centers like Guatemala City were expanding rapidly but unevenly. Poverty, inequality, and political repression characterized much of daily life.

The 1970s were especially tense. A military-led government ruled under a veneer of order while guerrilla movements and civil unrest brewed beneath the surface. This volatile mix of geography and humanity set the ominous stage.

A Country on the Brink: Political and Economic Tensions in the 1970s

For decades, Guatemala had been shackled by political instability. Military juntas cycled in power, often backed by entrenched oligarchies. The government’s relationship with indigenous populations was fraught with distrust and violence. Economic inequality was staggering: while the elites controlled fertile farms and urban capital, millions labored under harsh conditions and scant rights.

The early 1970s saw the seeds of insurgency sprout, with guerrilla factions gaining ground in rural zones. The government responded with brutal counterinsurgency campaigns. Against this backdrop, the country faced the daunting challenge of development: reconciling growth, security, and social justice under a state apparatus prone to repression.

Among these tensions, public infrastructure was fragile—earthquake-resistant engineering was rare outside the wealthiest enclaves. Rural communities lived in adobe homes and fragile structures, ill-equipped to face nature’s ire. This vulnerability was tragically revealed on that February morning.

The Morning of February 4: A Tremor Felt Beyond Borders

February 4, 1976, began in many villages and towns with the tranquility typical of highland mornings. Farmers tended crops, children moved through narrow streets, and markets buzzed with commerce. Then, just before 3:01 AM local time, the earth suddenly ruptured.

The seismic shock wave—the product of a rupture along the Motagua Fault—rippled through western Guatemala and reached even neighboring Honduras and El Salvador. The intensity was profound: it lasted less than a minute but the devastation was instantaneous.

Witnesses would later recount a terrifying cacophony: the roar of collapsing walls, trees snapping, and screams piercing the night. In Guatemala City, miles from the epicenter, alarm bells rang and thousands fled into the streets amid aftershocks. Communities closer to the epicenter bore the full brunt of the quake’s fury.

Magnitude and Mechanics: Understanding the 7.5 Richter Scale Event

Measured officially at magnitude 7.5, the 1976 earthquake released a tremendous amount of energy—equivalent to roughly 32 megatons of TNT. The source was a strike-slip rupture along the Motagua Fault, a major tectonic boundary where the North American and Caribbean Plates meet.

Unlike subduction-zone quakes, this was a lateral slip event, causing surface displacement by as much as several meters. The ground cracked open in places, roads buckled, and landslides cascaded down mountainous terrain.

For a country unprepared structurally and institutionally, this magnitude was catastrophic. Seismologists of the time noted that the earthquake’s intensity reached X (Extreme) on the Mercalli scale near the epicenter—meaning almost total destruction and widespread casualties.

The Epicenter’s Wrath: Chimaltenango and the Western Highlands under Siege

The earthquake’s epicenter was near the town of Los Amates in the department of Izabal, but the most devastating effects unfolded in the western highlands—in departments like Chimaltenango, Quetzaltenango, and Totonicapán.

Small rural towns constructed largely from adobe were obliterated. Roofs caved in, homes crumbled to dust, schools and churches—some centuries old—were lost. Villagers trapped beneath collapsed walls awaited rescue, many without hope.

The chaotic geography hampered aid. Mountain roads were severed, complicating access for emergency responders and relief workers. Hundreds of thousands now faced homelessness, thirst, hunger, and exposure to the cold February nights.

Collapse and Chaos: The Immediate Aftermath in Urban and Rural Areas

In Guatemala City—a sprawling metropolis of over a million—the earthquake toppled buildings and sparked fires. Although the city was distant from the epicenter, the shaking was powerful enough to bring down poorly constructed apartment blocks. The capital's infrastructure groaned under pressure, hospitals overwhelmed, and communication systems faltered.

Beyond the city, the rural crisis was incomparably worse. Villages were razed. Survivors wandered among the rubble, often without shelter or access to clean water. Casualty estimates vary, but official figures indicated over 23,000 dead and tens of thousands injured—a staggering toll for a nation of just over 4 million.

Panic spread as aftershocks rattled nerves and structures. Compounding the misery were cold temperatures and the heavy rains typical of the highland climate in February.

Human Stories Amid Ruins: Tales of Loss, Courage, and Survival

Among the statistics emerge deeply human stories. Maria, a mother of five from San Andrés Itzapa, remembered clutching her youngest child while their adobe home collapsed around them. Miraculously, they survived, but lost everything.

In Quetzaltenango, a group of schoolchildren trapped under rubble were saved by local volunteers digging through the night with bare hands. Community solidarity became the lifeline for many, even as official assistance lagged.

Yet grief was widespread. Families lost several members when entire neighborhoods crumbled. A poignant account from Huehuetenango tells of an entire extended family wiped out in a single mudslide.

These narratives paint a raw portrait of suffering, resilience, and the profound human cost behind the seismic figures.

The Role of the Guatemalan Government: Response and Controversies

The Guatemalan government, led by General Kjell Eugenio Laugerud García, declared a state of emergency and mobilized military and civil forces for rescue and relief. Early efforts focused on clearing debris, establishing emergency shelters, and distributing aid.

However, the response was marred by logistical challenges, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and allegations of corruption. Aid shipments were delayed or misappropriated. Some critics accused the regime of using disaster management as cover for increasing repression against dissidents.

Moreover, communication difficulties and rugged terrain slowed coordination. Many remote indigenous communities felt abandoned, fueling distrust toward the government.

Despite flaws, these early governmental actions laid groundwork for the enormous reconstruction task ahead.

International Aid: Support, Solidarity, and Geopolitical Undertones

The world responded swiftly. Countries across Latin America, North America, and Europe sent humanitarian aid, including food, medical supplies, and rescue teams. The United States, Mexico, and Cuba notably contributed, highlighting regional solidarity despite tense Cold War relations.

International organizations like the Red Cross and the United Nations dispatched teams to assist in relief and rebuilding efforts. This influx of aid was critical in stabilizing the crisis.

Yet, the disaster also became a stage for geopolitical posturing. The Guatemalan government courted Western allies by emphasizing anti-communist credentials and promising order, even as insurgencies simmered.

In some ways, the earthquake accelerated Guatemala's engagement with international humanitarian frameworks and disaster science.

The Role of the Military Junta: Between Assistance and Repression

Beneath the humanitarian front was a darker narrative. The military junta, tasked with disaster response, also intensified counterinsurgency operations amid internal upheaval.

In certain regions, relief efforts were tightly controlled, with suspicion targeted against indigenous communities perceived as potential guerrilla sympathizers. Reports emerged of discrimination in aid distribution and use of military checkpoints hindering access.

The earthquake exposed contradictions within the regime—simultaneously vulnerable and unbending—revealing structural weaknesses that would shape Guatemala’s continuing conflict through the late 20th century.

Reconstruction Efforts: The Long Road to Recovery

Physical rebuilding was a Herculean task. The government launched the National Reconstruction Committee, emphasizing the construction of earthquake-resistant homes and infrastructure.

International loans and aid funded construction projects and urban redevelopment. Yet, resources stretched thin amid political priorities and economic pressures.

Entire towns needed relocating or redesigning. For example, the historic center of Antigua Guatemala, though spared major damage, saw efforts to safeguard heritage against future tremors.

Reconstruction extended well into the 1980s, but many survivors continued to live in precarious conditions for years, underscoring the limits of post-disaster recovery.

Impact on Indigenous Communities: A Demographic and Cultural Catastrophe

Guatemala's indigenous Maya peoples bore a disproportionate share of the disaster’s toll. Villages built from unreinforced adobe were the most vulnerable. Many elders, keepers of linguistic and cultural traditions, perished.

Beyond the immediate physical impact, the earthquake exacerbated social marginalization. Displacement disrupted traditional agricultural cycles and communal relations.

Aid programs often failed to respect indigenous customs and languages, deepening alienation. Yet, indigenous communities also showed remarkable solidarity, rebuilding schools, churches, and homes with a combination of ancestral knowledge and external resources.

The 1976 quake remains a traumatic landmark in Maya history, shaping identity and political activism in subsequent decades.

Economic Costs and Development Setbacks

The economic cost was staggering—estimated between $400 million and $1 billion in 1976 USD, roughly 20-25% of the country's GDP at the time.

Agriculture, the backbone of the economy, was devastated in quake-stricken regions, with losses in crops like coffee and maize. Infrastructure destruction hindered transport and communication for months.

Foreign investment faltered amid instability, and poverty deepened. The disaster pushed back Guatemala’s developmental ambitions and compounded existing inequalities.

Reconstruction funds were limited and competed with military expenditures, underscoring the complex economic landscape.

The 1976 Earthquake in Memory and Culture: Art, Literature, and Collective Trauma

The quake resonated deeply beyond maps and statistics—seeping into art, literature, and collective memory.

Poets and writers memorialized loss and resilience; painters depicted shattered landscapes and human suffering. Annual commemorations became sites of collective mourning and reflection.

The trauma also found voice in political discourse, linking natural disaster to social injustice and government neglect.

In schools, history textbooks weave the earthquake into lessons on national identity, warning and testament to human fragility and endurance.

Advances in Seismology and Disaster Preparedness Spawned by the Tragedy

The 1976 earthquake spurred growth in Guatemala’s scientific and civil defense capacities. Seismological monitoring stations were expanded, and greater effort invested in earthquake-resistant building codes.

Emergency preparedness programs gradually developed, including drills and community education.

Though progress was uneven, the event marked the beginning of a more systematic approach to natural disasters in Guatemala, influencing policy and awareness nationally and regionally.

Reflections from Survivors: Voices from the Rubble

Survivors have continued to share stories both painful and hopeful decades later.

“I remember the earth shaking like the world was ending,” said Juan Carlos, a farmer from Chimaltenango. “But we rebuilt. We are still here.”

Many speak of lost family members, destroyed homes, but also of solidarity, courage, and faith.

These testimonies humanize a cataclysm, reminding us that history is not only what happened but what was lived, felt, and remembered.

The Earthquake as a Catalyst for Political Change?

While the disaster did not immediately topple the military government, it exposed vulnerabilities in state capacity and legitimacy.

Some scholars argue the quake indirectly fueled demands for reforms by highlighting inequality and governmental failures.

It arguably accelerated international scrutiny and internal debates over governance, human rights, and development models.

Yet, political upheaval took decades to unfold in Guatemala, shaped by myriad complex forces beyond the earthquake alone.

Comparative Perspectives: Guatemala 1976 and Global Earthquakes

The 1976 Guatemala Earthquake fits within a global pattern of seismic disasters striking vulnerable nations.

Comparisons with earthquakes in Chile (1960), Tangshan, China (1976), and later Mexico City (1985) reveal shared challenges: fragile infrastructure, poor planning, and political ramifications.

Each disaster instructs lessons in preparedness, humanitarian response, and social justice—making Guatemala’s experience part of a broader human story confronting nature’s power.

The Legacy 40 Years On: Remembrance and Lessons Learned

More than four decades later, the Guatemala Earthquake of 1976 remains a somber touchstone.

Memorials stand in ravaged communities; government and civil society observe anniversaries.

Disaster risk reduction continues to be a priority, with efforts embracing indigenous knowledge and scientific advances.

The quake’s legacy is a potent blend of sorrow and resilience, a call to confront geological hazards alongside social fragilities.

As survivors age and new generations rise, Guatemala carries the lessons of that fateful day forward—testimony to human endurance in the face of nature’s overwhelming force.

Conclusion

The 1976 Guatemala Earthquake was more than a cataclysmic geological event—it was a profound moment of rupture and revelation for a nation. It exposed the vulnerabilities of communities long marginalized, challenged a state struggling to assert control, and left scars on both land and soul. Yet, amid the rubble, stories of solidarity, resilience, and hope emerged, illuminating the indomitable spirit of a people.

This catastrophe reminds us that nature’s fury cannot be separated from the social landscapes it strikes. The earthquake’s legacy lives in Guatemala’s ongoing journey to build safer, more equitable societies, prepared not only to withstand the shaking ground but also to heal from its many aftershocks—social, political, and cultural.

The lessons of 1976 are timeless: in every catastrophe lies the potential for renewal, if we choose to learn, remember, and act with humanity.

FAQs

Q1: What caused the 1976 Guatemala Earthquake?

The earthquake was caused by a rupture along the Motagua Fault, a major strike-slip boundary between the North American and Caribbean tectonic plates. This geological fault line runs through western Guatemala, making the region prone to seismic activity.

Q2: How many people died in the 1976 earthquake?

Official estimates report over 23,000 fatalities. Many more were injured, and hundreds of thousands were left homeless.

Q3: How did the earthquake impact indigenous communities?

Indigenous Maya populations suffered disproportionately due to their location in rural areas with fragile housing. The quake caused significant demographic loss and cultural disruption, exacerbating historical marginalization.

Q4: What was the government’s response to the disaster?

The military government declared a state of emergency and mobilized limited rescue and relief efforts. However, the response was criticized for delays, corruption, and political manipulation that hindered effective aid delivery.

Q5: Did international aid play a role in recovery?

Yes. Countries, international organizations, and NGOs provided critical humanitarian aid. Assistance helped with immediate relief and reconstruction, even as geopolitical interests influenced some aid flows.

Q6: How did the earthquake influence Guatemala’s future disaster preparedness?

The 1976 quake led to increased investment in seismology, improved building codes, and the gradual development of emergency response systems.

Q7: Is the 1976 earthquake remembered in Guatemalan culture?

Indeed, it deeply shaped art, literature, and collective memory, becoming a reference point for national tragedy and resilience.

Q8: What lessons does the 1976 earthquake leave for today?

It underscores the need for equitable development, resilient infrastructure, and inclusive disaster planning that recognizes social as well as natural vulnerabilities.