Table of Contents

- The Dawn of a New Medium: China in the Early Second Century

- The Humble Origins of Paper: From Writing Materials to Innovation

- Cai Lun: The Man Behind the Revolution or a Symbol of a Collective Endeavor?

- The Early Manufacture of Paper: Techniques and Materials

- The Social and Political Climate of Han Dynasty China

- Why Paper? Challenges of Writing Before Its Invention

- The Spread of Paper Within China: From Court to Common Folk

- The Tang Dynasty and Paper: Elevating the Craft to an Art

- The Silk Road and the Diffusion of Paper to Central Asia

- Paper’s Journey to the Islamic World: Transformation and Innovation

- Paper in Medieval Europe: From Luxury Item to Popular Utility

- The Printing Revolution: Paper as the Catalyst of Knowledge Dissemination

- Economic and Cultural Impacts: Enabling Bureaucracy, Education, and Religion

- The Environmental and Material Significance of Paper’s Invention

- Myths, Legends, and Attribution: Rethinking Cai Lun’s Legacy

- Paper as a Symbol of Civilization and Progress

- The Long Shadow: From Invention to Modern Paper Industries

- Conclusion: Paper’s Quiet Revolution and Enduring Heritage

- FAQs: Unfolding the Story of Paper

- External Resource

- Internal Link

1. The Dawn of a New Medium: China in the Early Second Century

Imagine a quiet afternoon in the imperial workshops of Han Dynasty China. The year is 105 CE. Laborers are bustling, oils simmer on stoves, thin layers of revolutionary fibers float in vats, and scribes eagerly anticipate a writing surface finer than any silk or bamboo strip. In this moment, the invention of paper—an invention that would silently but irrevocably change human civilization—was blossoming.

The story of paper’s invention is not merely a tale of a new material; it is the key to understanding the agency and curiosity of ancient peoples wrestling with the demands of organizing empires, transmitting knowledge, and communicating across time and space. The age-old struggle to find an ideal medium for writing—one that is both durable and affordable—found an answer in a humble sheet made from mashed plant fibers and water. This breakthrough originated in China, and its ripples would eventually wash over the entire world.

2. The Humble Origins of Paper: From Writing Materials to Innovation

Before paper, writing in China was done mainly on bamboo strips and wooden tablets, or more luxuriously on silk fibers. Both media were either cumbersome, heavy, expensive, or laborious to produce. Bamboo slips, used widely during the Warring States period and early Han, had to be bound in stacks and were not suitable for voluminous texts or quick note-taking. Silk, while beautiful and smooth, was a costly commodity.

This context generated a stark demand: an inexpensive, light, and durable writing surface that could support the flourishing administration of the Han Empire and the expanding corpus of literature, philosophy, and bureaucratic documents. However, the technique to produce such material remained elusive until the early second century.

3. Cai Lun: The Man Behind the Revolution or a Symbol of a Collective Endeavor?

Cai Lun, a eunuch and official at the imperial court, is traditionally credited as the inventor of paper in 105 CE. Historical texts, particularly the official ‘Book of Later Han’ (Hou Hanshu), praise him for systematizing and improving papermaking techniques using materials like tree bark, hemp, rags, and fishing nets.

However, many modern historians argue that Cai Lun’s role was less that of a lone inventor and more that of an innovator who refined and popularized an existing craft. Prior forms of proto-paper existed in China and even elsewhere, but Cai Lun’s contribution was to create a standardized, replicable method that the government could deploy.

Whether hero or symbol, Cai Lun’s connection to paper signifies the importance of patronage, state backing, and the collective effort of artisans. His story illuminates the manner in which technological breakthroughs often grow not from a flash of genius but from gradual experimentation embedded in social and political structures.

4. The Early Manufacture of Paper: Techniques and Materials

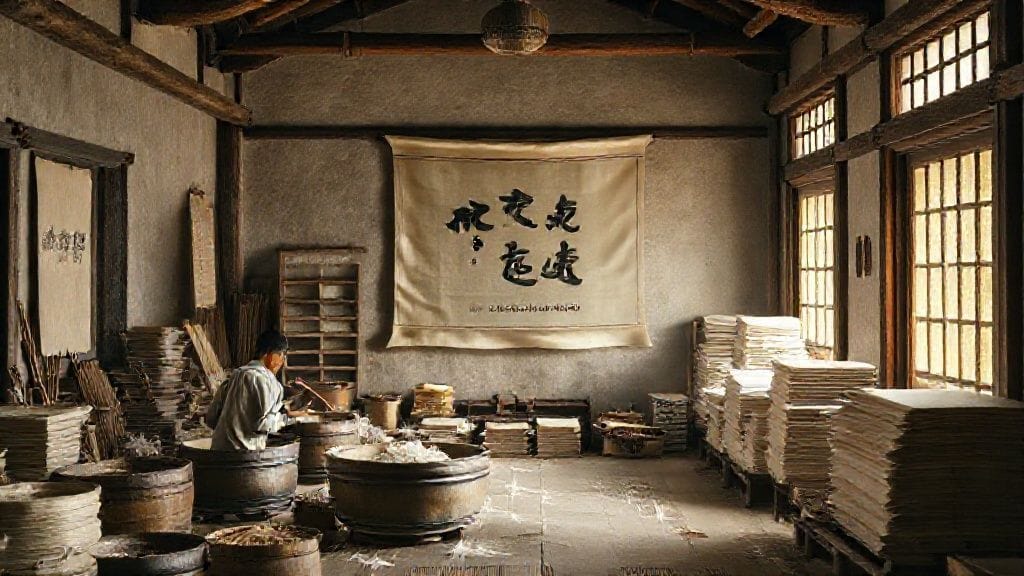

The earliest paper produced by Cai Lun and his workshop reportedly used mulberry bark, hemp, textile scraps, and fishing nets—fibrous materials beaten to a pulp, suspended in water, drained through a screen, and dried into thin sheets.

This revolutionary process allowed for far more uniform, lightweight, and flexible sheets compared to previous writing surfaces. The process itself was labor-intensive but scalable. Each step—from soaking and breaking fibers to pressing and drying—required knowledge and delicate attention.

This methodology laid the foundation for papermaking techniques that would evolve but remain recognizable over centuries.

5. The Social and Political Climate of Han Dynasty China

The Han Dynasty, ruling from 206 BCE to 220 CE, was one of China’s golden ages, marked by significant bureaucratic centralization, territorial expansion, and cultural achievements. The expansion and complexity of the imperial administration made writing indispensable.

Paper’s invention dovetailed with an era where documents proliferated: tax records, military dispatches, official decrees, historical chronicles, philosophical treatises, and literary creation all demanded better writing materials.

Moreover, the Confucian ideal of governance through education, documentation, and moral example reinforced the need for accessible writing.

6. Why Paper? Challenges of Writing Before Its Invention

Before paper, scribes coped with bamboo slips—heavy and difficult to transport—or silk—expensive and reserved for the elite. Wooden tablets and ostraca were also used sporadically but remained localized and limited.

The invention of paper dramatically lowered the economic and material barrier to writing. Paper was easier to produce, lighter to carry, and more adaptable—ideal for folding into books or scrolls.

This shift democratized information, allowing for broader literacy and closer communication between both government and society.

7. The Spread of Paper Within China: From Court to Common Folk

Initially reserved for court use and high officials, paper gradually trickled down to merchants, scholars, and artisans. As production costs decreased, its availability grew.

Schools began to employ paper for teaching calligraphy and writing, further embedding it within Chinese culture.

The widespread use of paper in poetry, painting, and government documentation from the Eastern Han to the subsequent dynasties gave birth to a flourishing tradition of literature and record keeping.

8. The Tang Dynasty and Paper: Elevating the Craft to an Art

During the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), papermaking reached new heights both technically and artistically. Innovations included improvements in bleaching, sizing, and decoration.

Paper’s influence expanded beyond administrative function to become a medium for painting, calligraphy, and poetry—the cultural pillars of Chinese identity.

The Tang period is often seen as the cultural zenith where paper symbolized refinement and cultural sophistication.

9. The Silk Road and the Diffusion of Paper to Central Asia

The Silk Road—a vast network of trade routes connecting East and West—was instrumental in the transmission of paper technology beyond Chinese borders.

By the 8th century, paper had found its way into Central Asia as it was adopted by communities along the trade corridors.

Merchant caravans carried not only silk and spices but also ideas and technological know-how, with paper playing a crucial role in taxing and recording trade.

10. Paper’s Journey to the Islamic World: Transformation and Innovation

Arab conquerors encountered papermaking techniques during their expansion into Central Asia. The Battle of Talas (751 CE) between the Abbasid Caliphate and Tang Chinese troops is often cited as a pivotal moment in the transfer of papermaking knowledge.

Once in the Islamic world, paper rapidly spread, and workshops in cities like Baghdad and Damascus refined the process, integrating new materials and techniques that improved paper’s quality.

Libraries, universities, and scholars in the Islamic Golden Age depended heavily on paper, catalyzing a flowering of science, philosophy, and literature.

11. Paper in Medieval Europe: From Luxury Item to Popular Utility

Paper reached Europe through the Islamic territories in the 12th century, initially a luxury for elite use. It took several centuries for paper to supplant parchment as the primary writing surface.

Medieval European papermakers developed local techniques, utilizing linen rags and water-powered mills, which increased production.

By the late Middle Ages, the use of paper had expanded with the rise of universities, literacy, and commerce.

12. The Printing Revolution: Paper as the Catalyst of Knowledge Dissemination

The invention of the movable-type printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1440 ignited an explosion in book production.

Paper, affordable and abundant, was the ideal substrate for printed texts, enabling mass production of books and pamphlets.

This democratization of knowledge fostered the Renaissance, Protestant Reformation, scientific progress, and eventually the modern era.

13. Economic and Cultural Impacts: Enabling Bureaucracy, Education, and Religion

Paper facilitated the ever-growing bureaucratic apparatuses of governments worldwide by enabling rapid documentation and communication.

Education systems expanded, as textbooks and notebooks became affordable.

Religious movements, from Christianity to Buddhism and Islam, used printed texts on paper for scripture dissemination.

Culturally, paper underpinned art, literature, and correspondence, threading a common fabric throughout societies.

14. The Environmental and Material Significance of Paper’s Invention

The invention of paper also brought challenges and innovations in resource management. Early papermaking demanded fibers from trees, hemp, and textiles, sometimes taxing local environments.

However, constant innovation led to sustainable techniques and recycling traditions, such as the use of rags.

Today’s ecological concerns continue to trace back to these ancient decisions, highlighting the complex relationship between technology and nature.

15. Myths, Legends, and Attribution: Rethinking Cai Lun’s Legacy

Aside from official histories, folklore embellishes the story of Cai Lun—at times portrayed as divinely inspired or blessed by imperial favor.

The question remains whether we should view him as the sole inventor or a representative figure for generations of creators.

This narrative tension teaches us how invention stories shape national identity, historical memory, and the glamorization of technological progress.

16. Paper as a Symbol of Civilization and Progress

Paper’s quiet invention illustrates the often invisible infrastructure of civilization—how a simple object can transform culture, governance, and communication.

It stands as a testament to human ingenuity—not through brute force or conquest, but through delicate craft and minds attuned to necessity.

The evolution from papyrus and inscriptions to paper marked a turning point toward a literate, interconnected world.

17. The Long Shadow: From Invention to Modern Paper Industries

Today, paper remains ubiquitous—from books and newspapers to packaging and currency—vital to daily life despite digital revolutions.

The global paper industry, originating over 1,900 years ago, continues refining production methods and grappling with sustainability.

Modern research on recycled fibers, tree plantation management, and biodegradable alternatives echoes the ancient quest to balance progress and preservation.

18. Conclusion: Paper’s Quiet Revolution and Enduring Heritage

Looking back at the murky waters of a Han workshop where fibers swirl, we appreciate paper not merely as material but as a silent revolution. It speaks of human desires to record, share, and build collective memory. Through war and peace, kingdoms and republics, paper has endured—a conduit for imagination, diplomacy, and knowledge.

From Cai Lun’s era to the printing presses of Europe and the digital printouts of today, paper remains a profound symbol of connectivity. Its invention teaches us that even a seemingly mundane object can ripple across millennia, reshaping destinies and cultures.

FAQs: Unfolding the Story of Paper

Q1: Why is Cai Lun credited with the invention of paper when papermaking existed before him?

Cai Lun is recognized mainly for refining and formalizing papermaking techniques, making the process more efficient and scalable. Earlier, rudimentary forms existed, but Cai Lun’s method allowed paper to become widely used.

Q2: What were the main materials used in the earliest Chinese paper?

The earliest paper was made from mulberry bark, hemp, rags of old cloth, and fishing nets—a mix of fibrous plant and textile waste beaten into pulp.

Q3: How did paper influence governance in Han China?

Paper simplified document creation, record-keeping, and communication, enabling more effective control over the vast empire’s bureaucracy and contributing to the state’s coherence.

Q4: How did papermaking spread beyond China?

Through the Silk Road, Central Asian cultures adopted papermaking, which was later transmitted to the Islamic world—especially after the Battle of Talas—and eventually reached Europe via Spain.

Q5: What role did paper play in the Islamic Golden Age?

Paper enabled the establishment of massive libraries and facilitated the copying and dissemination of scientific, philosophical, and literary texts, fostering cultural and intellectual flourishing.

Q6: How did paper contribute to the European Renaissance?

By providing an affordable medium for printing, paper underpinned the mass circulation of books, ideas, and artworks, fueling education, science, and religious reformations.

Q7: Has the invention of paper impacted environmental concerns historically?

Yes. The demand for raw materials—especially wood and textiles—has historically required resource management, and today, sustainability remains a critical issue in the paper industry.

Q8: Why does the story of paper’s invention remain relevant today?

Because it highlights human innovation, the dissemination of knowledge, and the evolution of technology that continues to shape our society, art, and communication.