Table of Contents

- The Final Day in Konya: December 17, 1273

- The World of Jalāl ad-Dīn Rūmī: Spirit and Scholarship

- From Balkh to Anatolia: The Journey that Forged a Mystic

- The Seljuk Sultanate of Rum: A Land of Confluence

- The Rise of a Poet-Saint: Rūmī’s Growing Influence

- The Mourning of a Mystic: Konya’s Reaction to Rūmī’s Passing

- The Whirling Dervishes and the Birth of the Mevlevi Order

- Manuscripts and Legacy: Preserving the Masnavi

- Spiritual Succession: Shams of Tabriz and Rūmī’s Inner Circle

- The Masnavi: An Ocean of Mystical Wisdom

- Rūmī’s Death and the Political Climate in 13th Century Anatolia

- The Impact of Mongol Invasions on Rūmī’s World

- Konya as a Pilgrimage Site: From 1273 to Today

- The Poetic Voice that Transcended Time and Borders

- Western Rediscovery and Modern Reverence

- Rūmī’s Influence on Contemporary Sufi Practice

- Controversies and Myths Surrounding Rūmī’s Death

- The Cultural and Linguistic Legacy of Rūmī’s Works

- Artistic Expressions Inspired by Rūmī’s Final Days

- The Eternal Dance: Rūmī’s Teachings Today

- Conclusion: A Mystic’s Farewell in a Changing World

- FAQs: Understanding Rūmī’s Death and Legacy

- External Resource

- Internal Link

The final rays of the dying sun filtered softly through the arches of the Seljuk-era mosque in Konya. December 17, 1273, was a quiet day on the surface—a day like any other in the bustling heart of the Sultanate of Rum. Yet, inside a simple chamber, a profound silence fell as Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī, the towering beacon of mystical poetry and Sufism, breathed his last. The air thickened with the grief of disciples and townsfolk alike, who knew that their spiritual guide—the divine poet who had spun words into whirls of transcendence—had passed beyond this mortal coil.

That evening in Konya was more than a farewell; it heralded the end of an epoch and the birth of an enduring spiritual legacy. The death of Rūmī, now almost seven and a half centuries ago, was not merely the closing of one life but the ignition of a mystical fire that would illuminate hearts across continents and centuries.

The World of Jalāl ad-Dīn Rūmī: Spirit and Scholarship

To grasp the profound resonance of Rūmī’s death, one must first understand the man himself—a scholar, a mystic, a poet whose verses distilled the ineffable. Born in 1207 in Balkh, nestled within the cultural mosaic of Khurasan, Rūmī matured amid the upheavals of the Mongol invasions and shifting political tides. His father, Bahā’ al-Dīn Valad, was a respected religious scholar, and the young Rūmī inherited a thirst not just for knowledge but for direct divine experience.

Rūmī’s philosophy defied simple categorization. He merged orthodox Islam with esoteric Sufi insights, emphasizing love as the central path to divine union. His works, the most famous of which—the Masnavi—are often called the “Quran in Persian,” transformed theological doctrine into heart-felt poetry. Yet, Rūmī was far more than a poet; he was a spiritual revolution incarnate.

From Balkh to Anatolia: The Journey that Forged a Mystic

The Mongol incursions forced Rūmī’s family westward, setting their course toward Anatolia. Konya, then capital of the Sultanate of Rum, became Rūmī’s final home. In this city, cradled between the Byzantine and Islamic worlds, Rūmī’s mystical consciousness blossomed.

Encountering Shams of Tabriz irrevocably altered Rūmī’s trajectory. Shams was both catalyst and mystery—a fierce spiritual presence who awakened Rūmī’s inner fire, inspiring the profound poetic explosion that defined his later years.

The Seljuk Sultanate of Rum: A Land of Confluence

Konya, in the 13th century, sat at an intersection of empires, cultures, and faiths. The Seljuk rulers fostered a vibrant milieu where Persian poetry, Islamic jurisprudence, and Byzantine legacies intertwined. Yet beneath the surface of flourishing cities and scholarship, tension brewed—Mongol threats loomed, and political fragmentation rattled the realms.

Rūmī’s poetry, steeped in universal love and transcendent unity, offered solace and perspective amid this volatility. His death would soon become a catalyst for both spiritual continuity and political symbolism.

The Rise of a Poet-Saint: Rūmī’s Growing Influence

By the time Rūmī passed away, his reputation extended beyond Konya’s walls. Literary circles revered him; devotees, drawn by his charisma and spiritual insight, formed circles of dance and meditation around his teachings. The very act of whirling—a physical enrapturement meant to emulate the cosmic rhythms of the universe—was being enshrined as an expression of mystical love.

The Mourning of a Mystic: Konya’s Reaction to Rūmī’s Passing

When news spread of Rūmī’s death on that cold December day, Konya was engulfed in mourning. Scholars, merchants, mystics, and common folk flooded his home and mosque to pay respects. Some accounts speak of communal weeping and spontaneous group recitations of his poems, as if to lock his spirit within words.

The mosque where he taught became a sanctuary, and his tomb quickly transformed into a sacred site. It is said that even the whirling dervishes danced in the cold moonlight that night, their spinning embodying the cycle of life and death—a fitting tribute to their master.

The Whirling Dervishes and the Birth of the Mevlevi Order

Rūmī’s death, paradoxically, breathed life into institutionalized Sufism. The Mevlevi Order, founded by his son Sultan Walad, crystallized around Rūmī’s teachings, poetry, and philosophy. Their ritual dances—the Sema—became meditative journeys echoing Rūmī’s spiritual path.

The Mevlevis, donning tall hats symbolizing the tombstone of the ego and flowing robes representing the shroud, danced as a living homage to the departed master. This tradition remains one of the most enduring legacies of Rūmī’s life and death.

Manuscripts and Legacy: Preserving the Masnavi

Before his death, Rūmī had labored over the Masnavi, a vast six-book poetic magnum opus exploring divine love, the soul’s journey, and mystical philosophy. His disciples faithfully copied and disseminated these texts, ensuring the survival of the work through centuries.

These manuscripts served not just as books but as vessels of spiritual transmission. Illuminated and often richly adorned, the Masnavi became a cornerstone of Persian literature and an essential reference for Sufi seekers.

Spiritual Succession: Shams of Tabriz and Rūmī’s Inner Circle

Though Shams had disappeared years earlier under shadowed circumstances, his impact remained central after Rūmī’s death. The mystic circle around Rūmī consisted of devoted students, including family members and spiritual heirs, who shaped the interpretive tradition of the poetry.

Rūmī’s own sons, especially Sultan Walad, were instrumental in structuring the Mevlevi Order and systematizing their ceremonials, blending tradition with the evolving spiritual landscape of Anatolia.

The Masnavi: An Ocean of Mystical Wisdom

Few works in the annals of spiritual literature rival the Masnavi in scope and depth. It is a resonant symphony of parables, exhortations, and philosophical dialogues. In the aftermath of Rūmī’s death, the Masnavi became a spiritual beacon, guiding seekers toward inner illumination.

This text’s influence traversed beyond strictly Islamic contexts, permeating philosophical and poetic traditions worldwide, demonstrating the universality of Rūmī’s vision.

Rūmī’s Death and the Political Climate in 13th Century Anatolia

The 1270s were turbulent for Anatolia. The Mongol Ilkhanate exercised suzerainty over the Seljuk sultanate, stifling autonomy and precipitating regional instability. Among such unrest, Rūmī’s teachings offered a stabilizing spiritual ideal.

His death occurred amid these tensions; one can imagine in the collective sorrow a deeper reflection on impermanence and hope for transcendence during uncertain political times.

The Impact of Mongol Invasions on Rūmī’s World

The Mongol hordes’ advance forced population displacements and cultural shifts that shaped Rūmī’s trajectory. His family’s flight westward and the shifting centers of Muslim thought to Anatolia were direct results of Mongol expansion.

These upheavals forged a context in which Rūmī’s message of universal love and spiritual unity resonated deeply, offering hope amid chaos.

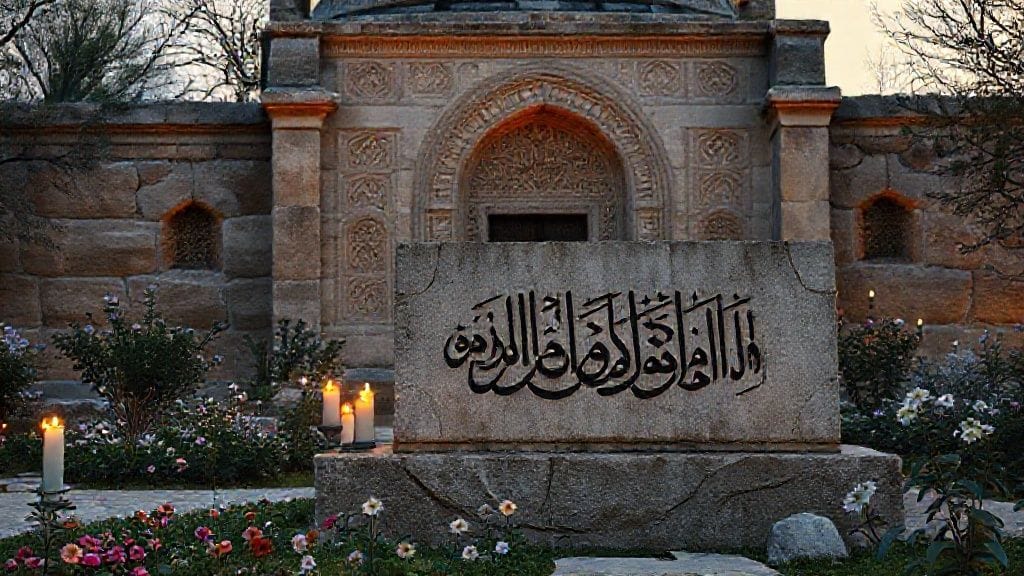

Konya as a Pilgrimage Site: From 1273 to Today

Rūmī’s tomb, the Mausoleum of Mevlâna, quickly became a pilgrimage destination. Through centuries, millions have journeyed to Konya to honor the mystic poet.

The annual Urs festival, commemorating Rūmī’s death anniversary, is a vibrant celebration blending religious ceremony, poetry, music, and dance, a living testament to the enduring spirit of the poet.

The Poetic Voice that Transcended Time and Borders

Why does Rūmī’s death resonate so profoundly, centuries later? Because his voice spoke to the human condition at its core—love, loss, longing, and hope.

His lines have traversed linguistic and cultural boundaries, from Persian to Turkish, Urdu, English, and beyond, continuing to inspire millions with the promise of union beyond division.

Western Rediscovery and Modern Reverence

Rūmī’s prominence in the Western world rose notably in the 20th century, thanks to translations like those by Coleman Barks. From academic halls to popular culture, Rūmī’s work found new audiences, often appreciated as spiritual poetry devoid of rigid doctrines.

This Western embrace underscores the universal appeal embedded in his mysticism and the melancholic beauty of his death’s memory.

Rūmī’s Influence on Contemporary Sufi Practice

Modern Sufi orders and spiritual practitioners continue to draw from Rūmī’s works and the Mevlevi tradition. His teachings on love, tolerance, and the inner journey remain potent tools for spiritual renewal, bridging centuries of faith practice.

This living tradition testifies that death was a passage, not an end, for Rūmī’s vibrant spiritual legacy.

Controversies and Myths Surrounding Rūmī’s Death

As with many figures enveloped in reverence, myths surround Rūmī’s final days—from tales of visions to miraculous occurrences at his passing. Some narrate that his death was accompanied by celestial music or that the earth itself mourned.

While historical accuracy is elusive, these stories deepen the emotional layer of his legacy, illustrating how he transcended mortal bounds in the cultural imagination.

The Cultural and Linguistic Legacy of Rūmī’s Works

Rūmī’s choice to write primarily in Persian, rather than Arabic, was significant, making his teachings accessible to a broad audience across Muslim lands and later Ottoman domains. His poetry influenced not only religious thought but also linguistics, music, and the arts.

His death marked the closure of a prolific era yet unsealed a cascade of cultural efflorescence that persists vibrantly.

Artistic Expressions Inspired by Rūmī’s Final Days

Paintings, calligraphy, music, and dance have all drawn inspiration from the theme of Rūmī’s death and the spiritual journey it symbolizes. Ottoman miniatures depict the whirling dervishes spinning in nighttime vigils; contemporary art installations explore his mysticism and mortality.

Such creations transform the historical event into a multisensory dialogue between past and present.

The Eternal Dance: Rūmī’s Teachings Today

Rūmī’s death did not silence his voice; instead, it propelled the symbolic dance of spiritual ecstasy. The whirling dervishes spin in his honor, each rotation a step closer to the divine.

In a fractured world, Rūmī’s universal call to love and unity remains not just poetry—but a lived experience and a global spiritual heritage.

Conclusion

Jalāl ad-Dīn Rūmī’s death on December 17, 1273, was more than the passing of a man; it was the metamorphosis of a living legend into a timeless legacy. In the quiet streets of Konya, sorrow gave way to reverence, loss to spiritual awakening. His words, spun like celestial silk, continue to bind humanity in an eternal embrace. From the whirling dances to the quiet recitations in distant lands, Rūmī’s soul dances on.

In a world often fractured by difference, the poet of Rum teaches us that death is but a doorway—and that love, above all, is the path home.

FAQs

Q1: What caused Jalāl ad-Dīn Rūmī’s death?

A1: Rūmī died of natural causes in Konya at the age of 66. Historical records indicate illness and age as primary factors, though exact medical details are unavailable.

Q2: How did Rūmī’s death affect his followers immediately?

A2: His death triggered deep mourning in Konya. Followers formed the initial nucleus of the Mevlevi Order to preserve and propagate his teachings and practices, continuing his spiritual legacy.

Q3: Why is Rūmī buried in Konya rather than his birthplace in Balkh?

A3: Rūmī spent the last decades of his life in Konya, which became his spiritual and physical home. After his death, he was interred there, turning the city into a spiritual hub and pilgrimage site.

Q4: What is the significance of the Mevlevi Order in relation to Rūmī’s death?

A4: The Mevlevi Order was founded posthumously to honor Rūmī’s mystical teachings. The order institutionalized his poetic and spiritual philosophy through ritual, dance, and communal discipline.

Q5: How did political events in the 13th century influence Rūmī’s final years?

A5: The Mongol invasions and Seljuk political complexities created a backdrop of uncertainty. Rūmī’s message offered spiritual refuge, while Konya’s relative safety allowed his work to flourish.

Q6: What role does Rūmī’s death anniversary (Urs) play today?

A6: The Urs festival commemorates Rūmī’s death as a “wedding night” — a union with the divine—celebrated through music, poetry, and the iconic whirling dances, attracting pilgrims worldwide.

Q7: Are there any controversies surrounding the circumstances of Rūmī’s death?

A7: While historical accounts agree on his natural death, myths about miraculous events surrounding his passing exist, enriching his mystique but lacking documentary evidence.

Q8: How has Rūmī’s death influenced global perceptions of Sufism?

A8: His death solidified his status as a saint and symbol of divine love, shaping global appreciation of Sufism as a path centered on love, tolerance, and poetic expression.