Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Birth and Childhood in Weil der Stadt

- Education and Early Fascination with the Stars

- Meeting Tycho Brahe

- The First Steps Toward the Laws of Planetary Motion

- The Three Laws Explained

- Kepler’s Religious and Philosophical Views

- Challenges and Personal Struggles

- Kepler’s Other Scientific Contributions

- Legacy in Astronomy and Science

- Anecdotes and Lesser-Known Facts

- Death and Memory

- External Resource

- Internal Link

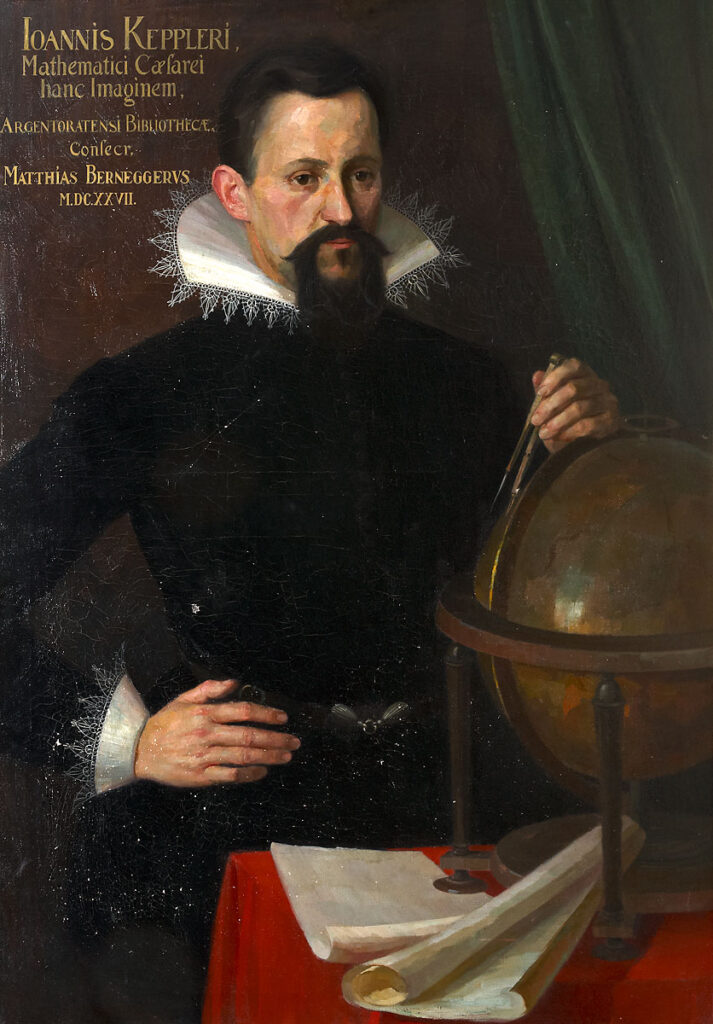

Introduction

Johannes Kepler, one of the towering figures of the Scientific Revolution, was born on December 27, 1571, in Weil der Stadt, a small town in what is now southwestern Germany. Kepler’s name is forever tied to the laws of planetary motion — three elegant principles that transformed our understanding of the cosmos. Imagine living in a time when people still debated whether the Earth moved at all, and then daring to prove mathematically that planets follow precise, predictable paths. It’s nothing short of breathtaking, isn’t it?

Birth and Childhood in Weil der Stadt

Weil der Stadt in the late 16th century was a modest settlement, surrounded by rolling hills and bustling markets. Kepler was born into a family of humble means; his father, Heinrich Kepler, was a mercenary soldier, and his mother, Katharina Guldenmann, was an herbalist.

Johannes was a sickly child, suffering from illnesses that left him physically frail. But his sharp mind and curiosity were evident early on. He recalled in later writings that at age six, his mother took him to see the Great Comet of 1577 — a sight that may have planted the first seeds of his astronomical passion.

Education and Early Fascination with the Stars

Kepler attended local schools before earning a scholarship to the University of Tübingen. There, he studied under the mathematician Michael Maestlin, a supporter of Copernicus’s heliocentric theory. While most scholars still clung to the idea of an Earth-centered universe, Kepler embraced the radical notion that the planets revolved around the Sun.

In 1594, he accepted a teaching position in Graz, Austria, where he began developing his ideas about the geometric relationships between planetary orbits. He published his first major work, Mysterium Cosmographicum, in 1596, proposing that the spacing of the planets could be explained using nested Platonic solids — a beautiful idea, though not entirely accurate.

Meeting Tycho Brahe

In 1600, Kepler’s life took a decisive turn when he met the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe in Prague. Tycho had compiled the most precise astronomical observations of the time, and Kepler recognized that this data could either confirm or destroy his theories.

The partnership was intense and sometimes difficult — Tycho was protective of his data, while Kepler was impatient to use it. But after Tycho’s death in 1601, Kepler inherited the position of imperial mathematician and gained full access to the treasure trove of observations.

The First Steps Toward the Laws of Planetary Motion

Kepler initially set out to determine the orbit of Mars, a planet whose path stubbornly resisted explanation under the perfect circles demanded by ancient astronomy. After years of painstaking calculations, he realized that the orbit was not circular but elliptical. This was a revolutionary insight — breaking with centuries of tradition and opening the door to his first law of planetary motion.

The Three Laws Explained

- First Law – The Law of Ellipses

Planets move in elliptical orbits with the Sun at one focus. - Second Law – The Law of Equal Areas

A line connecting a planet to the Sun sweeps out equal areas in equal times, meaning planets move faster when closer to the Sun. - Third Law – The Harmonic Law

The square of a planet’s orbital period is proportional to the cube of its average distance from the Sun.

These laws not only described planetary motion accurately but also laid the groundwork for Newton’s theory of gravitation decades later.

Kepler’s Religious and Philosophical Views

Kepler saw his work as uncovering the mathematical order of God’s creation. To him, the harmony of the cosmos reflected divine design. He often blended rigorous mathematics with poetic language, describing the universe as a grand musical composition in which each planet played its part.

Challenges and Personal Struggles

Kepler’s life was far from easy. He faced political turmoil, financial difficulties, and personal tragedies, including the deaths of several of his children. His mother was accused of witchcraft in 1615, and Kepler personally defended her in court, securing her release after a long legal battle.

Kepler’s Other Scientific Contributions

Beyond astronomy, Kepler made advances in optics, explaining how vision works and improving telescope design. His work Astronomia Nova, Harmonices Mundi, and Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae became foundational texts in astronomy.

He also developed methods for calculating volumes and areas that foreshadowed integral calculus.

Legacy in Astronomy and Science

Kepler’s insights permanently changed the way we view our place in the universe. His laws provided the essential link between the observations of Tycho Brahe and the theories of Isaac Newton, bridging the gap between medieval and modern science.

Today, his name lives on in the Kepler Space Telescope, which has discovered thousands of exoplanets — a fitting tribute to a man who dedicated his life to understanding the heavens.

Anecdotes and Lesser-Known Facts

- Kepler was fascinated by astrology early in life, but he approached it with skepticism, using it more as a tool for public engagement than personal belief.

- He once calculated the year of Jesus’s birth based on astronomical events, arguing it was 4 BC.

- Kepler’s favorite geometric shape was the ellipse — not only for planets but as a symbol of imperfection revealing deeper beauty.

Death and Memory

Johannes Kepler died on November 15, 1630, in Regensburg. Though his grave was lost during later wars, his writings and discoveries endure, still inspiring scientists and dreamers alike.