Table of Contents

- The Dawn of a New Vision: Birth of the Kinetograph in 1888

- Thomas Edison and William Kennedy Laurie Dickson: The Pioneers Behind the Machine

- The World Before Moving Pictures: Entertainment and Technology in the Late 19th Century

- Inventing the Kinetograph: Engineering Marvel Amidst Scientific Curiosity

- The First Recorded Motion: Capturing Life in Frames

- Early Experiments and the Role of the Kinetoscope

- The Kinetograph’s Technical Innovations: Light, Film, and Mechanics

- Challenges and Failures: Overcoming the Limits of Early Film Technology

- The Public’s First Glimpse of Moving Images: Exhibitions and Reactions

- The Sociocultural Impact of the Kinetograph: Changing Perceptions of Reality

- The Kinetograph and the Birth of the Film Industry

- Competition and Collaboration: Other Pioneers Enter the Scene

- The Transition from Kinetograph to Projection: The Next Leap Forward

- Legal Battles and Patent Wars Surrounding the Kinetograph

- From Edison’s Lab to Global Icon: The Kinetograph’s Journey

- Legacy and Influence: How the Kinetograph Shaped Modern Cinema

- The Kinetograph in Popular Memory and Historiography

- Anecdotes and Untold Stories: Human Faces Behind the Machine

- Technological Descendants: Tracing the Evolution of Film Cameras

- Cultural Reflections: The Kinetograph as a Symbol of Modernity

- Conclusion: The Enduring Magic of the First Moving Camera

- FAQs About the Kinetograph Film Camera’s Creation and Impact

- External Resource

- Internal Link

The Dawn of a New Vision: Birth of the Kinetograph in 1888

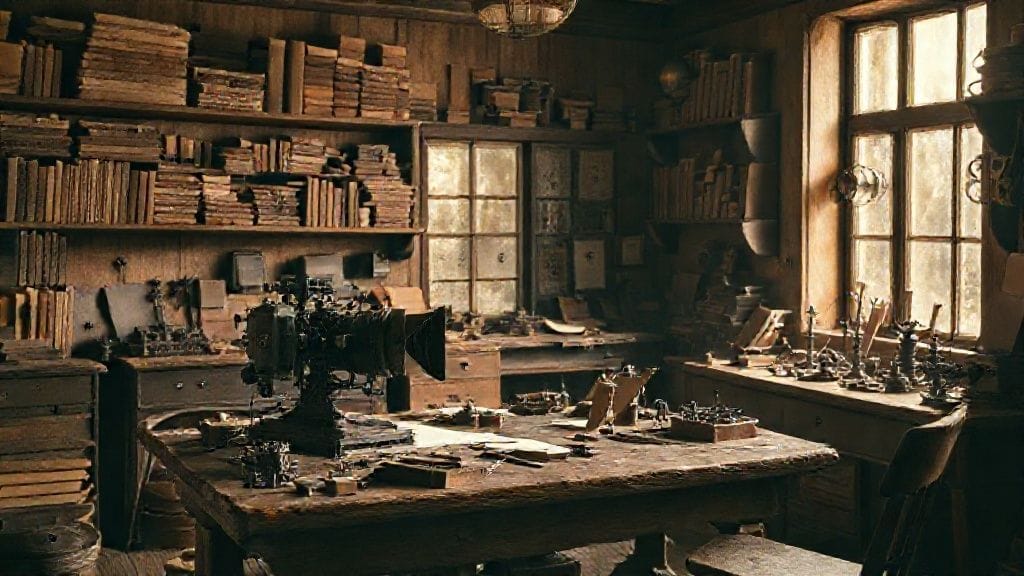

It was a crisp autumn day in 1888 when, inside a cluttered laboratory filled with humming machinery and flickering gas lamps, a silent revolution began. The laboratory, tucked away in the heart of Menlo Park, New Jersey, bore witness to the birth of a device that would forever transform how humanity perceived time, memory, and storytelling—the kinetograph film camera. With wooden levers, intricate gears, and the delicate thread of celluloid film, the kinetograph captured motion for the first time in history. Suddenly, the world could be recorded frame by frame, breathing life into static moments.

Imagine the wonder in the eyes of Thomas Edison and his assistant, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, as the kinetograph clicked and wound, revealing images that moved just as people did. This was no ordinary machine — it was a gateway to a new medium, an art form and science blended into one. The kinetograph did not only freeze time; it made it dance.

Thomas Edison and William Kennedy Laurie Dickson: The Pioneers Behind the Machine

To understand the kinetograph, we must first meet the minds behind its creation. Thomas Edison, the prolific American inventor best known for the electric lightbulb, had long been fascinated with sound and motion. Yet it was William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, a Scottish-born photographer and inventor, who became Edison’s right hand in this venture.

Dickson, a man of sharp intellect and profound technical skill, translated Edison’s vision into engineering reality. Together, they embarked on a journey to create a device capable of recording motion pictures—moving beyond the phonograph’s sound recordings to pictures that moved with time. Their partnership was collaborative and sometimes fraught, but their determination was relentless.

The World Before Moving Pictures: Entertainment and Technology in the Late 19th Century

Before the kinetograph, people’s entertainment was rooted in live performances—vaudeville shows, theater, magic lantern slides, and panoramas. Photographs were static images, cherished but frozen in time. Novel inventions like the zoetrope offered illusions of motion but lacked permanence. The thirst for visual storytelling was palpable, yet technology had yet to catch up.

Scientific optimism thrived in the late 1800s, and inventors raced to translate electricity, chemistry, and optics into practical tools. Photography itself was barely fifty years old but was already widespread. What if photography could move, mimicking life rather than merely capturing it?

Inventing the Kinetograph: Engineering Marvel Amidst Scientific Curiosity

Edison’s laboratory became a crucible of invention. The kinetograph was designed to harness the power of celluloid strips to expose a rapid series of images—forty frames per second—to capture continuous motion. The mechanism was intricate: a claw moved the film incrementally, stopping it briefly for each image to be exposed to light.

Precision was critical. The challenge was to synchronize film movement, exposure, and illumination inside a compact apparatus. The camera resembled a wooden box with lenses and crank handles, deceptively simple in appearance but complex inside.

Dickson recalls later, “We struggled endlessly with the feeding mechanism. The film had to advance without tearing, without jerking, all in perfect rhythm with the shutter.”

The First Recorded Motion: Capturing Life in Frames

Among the earliest films shot by the kinetograph was the now-legendary “Dickson Greeting” (1891)—a thirteen-second clip where Dickson himself bows and doffs his hat. Another famous recording was “Blacksmith Scene,” showing workers hammering metal rhythmically.

These moving images were revolutionary: the camera froze reality frame by frame yet presented it in continuous motion, creating an illusion no viewer had seen before. Audiences could now witness time itself rendered in seconds, reshaping the boundaries between reality and its representations.

Early Experiments and the Role of the Kinetoscope

But what good was the kinetograph without a way to view its films? The answer was the kinetoscope, also invented by Edison’s team. This peephole viewer allowed a single person to watch the short motion pictures looped endlessly.

In 1894, kinetoscope parlors sprang up in New York, inviting paying customers to experience this new magic. Though rudimentary, the public’s reaction was electric. “It’s like watching life itself,” proclaimed one amazed visitor, “as if the soul of a moment is captured inside glass.”

The Kinetograph’s Technical Innovations: Light, Film, and Mechanics

Celluloid film, imported from Europe, was the unsung hero enabling the kinetograph’s success. This flexible, transparent strip was coated with light-sensitive chemicals, which the kinetograph exposed rapidly through a precise shutter.

The intermittent movement, the claw mechanism, and the shutter’s timing—these engineering feats were critical to producing clear, stable images. Edison and Dickson’s ingenuity bridged photography and motion, turning technical hurdles into creative triumphs.

Challenges and Failures: Overcoming the Limits of Early Film Technology

However, this triumph was not without its setbacks. Film was fragile and flammable; exposure times were limited; cameras bulky and difficult to transport; and the kinetoscope’s solo viewing format restricted audience reach. Additionally, Edison’s team grappled with patenting battles and competitors eager to develop projection systems that could show films to larger crowds.

Yet, with each limitation, Edison’s team innovated. The kinetograph’s frame rate was improved, exposure reduced, and more durable film stocks examined. But these struggles highlight that progress is never instantaneous but the product of persistent trial.

The Public’s First Glimpse of Moving Images: Exhibitions and Reactions

The kinetoscope exhibitions in 1894 and afterward were the first occasions for the public to glimpse “living photographs.” People lined up to witness scenes of boxing matches, dancers, and daily life—the ordinary now extraordinary.

These moments resonated deeply. One visitor later wrote, “To see a man walking on film was like looking into a window of the future—a future made of light and shadow.” The reaction was a mixture of wonder, disbelief, and excitement—a harbinger for society’s profound embrace of cinema.

The Sociocultural Impact of the Kinetograph: Changing Perceptions of Reality

The kinetograph did more than entertain; it altered human perception. Suddenly, reality could be cataloged and replayed endlessly, encapsulating not just images but motion and emotion. This had profound implications culturally—visual journalism would become possible, theatrical performances immortalized, and the very concept of time challenged.

Philosophers and artists debated what this meant. Was moving film a new kind of reality, or simply an illusion? The kinetograph introduced a visual language that democratized storytelling, giving the masses access to experiences once exclusive.

The Kinetograph and the Birth of the Film Industry

Edison’s invention laid the foundation for a burgeoning film industry. Entrepreneurs recognized the potential to create, market, and distribute films. Studios arose; narrative storytelling replaced mere recorded scenes. The kinetograph transitioned from mere novelty to an essential tool in mass entertainment, culture, and communication.

Without this invention, the sprawling global cinema complex of the 20th century might never have been born.

Competition and Collaboration: Other Pioneers Enter the Scene

It wasn’t long before rivals such as the Lumière brothers in France—with their cinematograph—and Georges Méliès took inspiration and pushed film technology further, introducing projection and narrative complexity.

These innovators, sometimes competitors, sometimes collaborators, shaped the rapid evolution of film technology. Edison’s patents would face legal challenges, but his kinetograph remained a prototype for motion pictures worldwide.

The Transition from Kinetograph to Projection: The Next Leap Forward

Despite its success, the kinetograph was eventually eclipsed by projection systems that allowed large audiences to watch simultaneously. The kinetoscope’s solo experience would give way to the communal magic of the movie theater.

Yet, the kinetograph’s technical innovations remained at the heart of film cameras for decades. It was the bridge from still photography to the age of projected moving pictures.

Legal Battles and Patent Wars Surrounding the Kinetograph

The race to dominate the new film technology market was fierce. Edison’s aggressive defense of his kinetograph and kinetoscope patents led to several famous court battles. These patent wars shaped the early business landscape of cinema, sometimes stifling innovation but also safeguarding intellectual property.

This fierce legal environment underscored the immense value and potential held by the kinetograph.

From Edison’s Lab to Global Icon: The Kinetograph’s Journey

From the moment Edison and Dickson wound the first roll of film, the kinetograph’s influence spread far and wide. The machine journeyed from a small New Jersey lab to exhibitions across the United States and Europe, inspiring filmmakers and inventors alike.

It became a symbol—not just of technological progress but of a new way for humans to narrate their world.

Legacy and Influence: How the Kinetograph Shaped Modern Cinema

The kinetograph’s legacy is colossal. Its basic principles inform every modern film camera, from Hollywood blockbusters to smartphone cameras. By allowing motion to be captured and replayed, it changed everything: art, politics, communication.

Cinema grew into the “seventh art,” but without the kinetograph, the storytelling potential of moving images might have remained impossible.

The Kinetograph in Popular Memory and Historiography

While Edison often receives most historical credit, scholarly reassessment has highlighted Dickson’s crucial role and contributions of lesser-known collaborators. Popular memory sometimes simplifies history, but historians have sought a nuanced understanding of the kinetograph’s invention.

Its story is also intertwined with narratives of invention, commerce, and cultural transformation.

Anecdotes and Untold Stories: Human Faces Behind the Machine

Behind the clatter and invention were human stories: Dickson’s passion and frustrations; Edison’s visionary persistence; the operators who posed patiently for early films. One popular story recounts Dickson “dancing” endlessly in front of the camera to test frame rates—an image frozen in time as a man and a machine co-created history.

Technological Descendants: Tracing the Evolution of Film Cameras

From the kinetograph to the handheld digital cameras of today, the technology has evolved enormously. Yet, the fundamental challenge—capturing light and motion reliably—remains the same. The kinetograph was the first stepping stone in this long climb toward ever more sophisticated moving image machines.

Cultural Reflections: The Kinetograph as a Symbol of Modernity

The kinetograph epitomized the late 19th-century faith in technological progress and the emerging modern world. It symbolized a shift in how time and space could be conceptualized and represented, heralding the age of media and global communication.

Conclusion: The Enduring Magic of the First Moving Camera

The creation of the kinetograph film camera in 1888 was more than just a technological breakthrough—it was a moment when humanity captivated life itself, freezing the ephemeral into eternity. This machine opened doors to new artistic possibilities, societal reflections, and cultural revolutions.

Thomas Edison and William Kennedy Laurie Dickson did not just build a camera; they crafted a new language of sight and time. Over a century later, the magic that sparked in that Menlo Park lab continues to enchant us all.

Conclusion

The kinetograph’s story is a testament to human curiosity, creativity, and the drive to overcome obstacles. It reminds us that each frame of a film is a thread in the vast tapestry of culture, memory, and technology. More than a machine, the kinetograph is a symbol of transformation—how light, mechanics, and human ingenuity combined to alter our perception of reality forever.

From the flickering images watched through a kinetoscope’s peephole to the global cinema screens of today, the journey began with the vision of capturing motion itself. As we watch modern films, streaming images into millions of homes, it is humbling and inspiring to remember the kinetograph—the first camera that dared to freeze movement in time.

FAQs About the Kinetograph Film Camera’s Creation and Impact

Q1: Who invented the kinetograph film camera?

The kinetograph was invented primarily by Thomas Edison’s team, with William Kennedy Laurie Dickson playing a pivotal role in its engineering and development.

Q2: What year was the kinetograph created?

The kinetograph was created in 1888, with key developments and first successful films appearing in the early 1890s.

Q3: How did the kinetograph work?

It used celluloid film strips moved intermittently by a claw mechanism, exposing frames rapidly to capture a sequence of images that, when viewed in succession, created the illusion of motion.

Q4: What was the kinetoscope?

The kinetoscope was the viewing device invented alongside the kinetograph, allowing a single viewer to watch motion pictures through a peephole viewer.

Q5: Why is the kinetograph important in film history?

It marked the first practical method to record moving images, laying the technical foundation for all future film cameras and the entire motion picture industry.

Q6: Were there any legal disputes related to the kinetograph?

Yes, Edison aggressively defended patents related to the kinetograph and kinetoscope, leading to several patent wars that shaped early cinema business.

Q7: How did audiences initially react to kinetograph films?

Audiences were amazed and fascinated, describing the experience as magical and revolutionary since they had never seen moving pictures before.

Q8: What is the legacy of the kinetograph today?

The kinetograph’s fundamental technology influenced all subsequent cameras, making it the ancestor of modern film and digital motion picture devices.