Table of Contents

- The Fiery Awakening: Lanín’s First Great Roar in 1826

- The Land of Fire and Ice: Geographical and Cultural Setting

- Ancient Giants: Geological Origins of Lanín Volcano

- The Calm Before the Storm: Pre-1826 Conditions and Indigenous Knowledge

- Sparks in the Silence: Early Signs of the Eruption

- The Earth Trembles: The First Explosive Phase

- Rivers of Fire: Lava Flows and Pyroclastic Surges Beyond the Summit

- Clouds of Ash and Sky Darkened: Atmospheric Impact and Eyewitness Accounts

- Between Two Nations: The Shared Challenge for Argentina and Chile

- Human Stories amidst Nature’s Fury: Indigenous and Settler Responses

- Mapping Disaster: Early Scientific Observations and Misinterpretations

- The Aftermath: Environmental and Ecological Transformations

- Political Consequences: How the Eruption Influenced Border Relations

- The Volcano in the Memory of Nations: Oral Traditions and Chronicles

- Lessons from Lanín: Early 19th-Century Volcanology’s First Test

- Lanín’s Dormancy and Subsequent Activity: Tracing the Volcano's Later History

- The Modern Legacy: Lanín in Science, Culture, and Conservation

- Conclusion: Nature’s Indomitable Voice Through Lanín’s Fury

- FAQs: Understanding the 1826 Lanín Eruption

- External Resource

- Internal Link

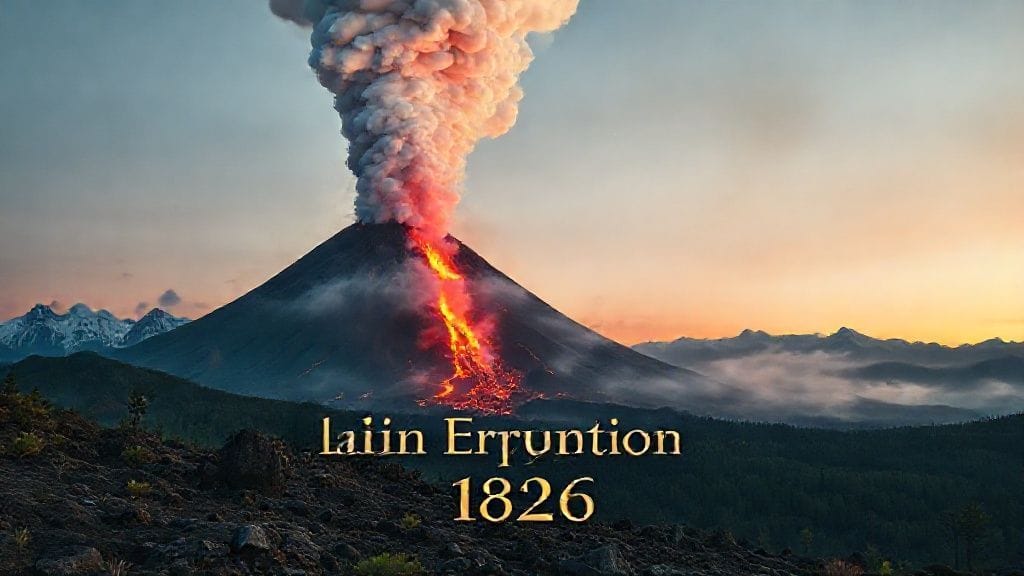

The Fiery Awakening: Lanín’s First Great Roar in 1826

It was the year 1826 when the mighty Lanín volcano, a sentinel perched high on the jagged border between Argentina and Chile, shook the eager eyes of the world as it burst back to life. For days and nights on end, the sky churned with smoke and ash, a fiery breath that illuminated the remote Patagonian wilderness. This eruption, one of the earliest recorded in the region’s modern history, was as much a natural spectacle as a crucible where human and geological histories intertwined fiercely. Those who witnessed it recalled the earth’s deep rumblings echoing through valleys, the skies darkened by ash so thick it snuffed out the mid-day sun, and rivers of molten rock cascading relentlessly down the volcano’s slopes.

Such a moment etched itself into the collective memory of those inhabiting the southern Andes and left marks—both physical and cultural—that continue to reverberate centuries later.

The Land of Fire and Ice: Geographical and Cultural Setting

Lanín volcano holds a proud stance at roughly 3,747 meters above sea level. Nestled snugly within the Andes mountain range, it commands attention not only for its height but for the dramatic juxtaposition of its fiery core and the snow-capped peaks that crown its summit. The volcano lies precisely along the watershed that separates Argentina’s Neuquén province from Chile’s Los Ríos region, a location rich in natural beauty but also a historical flashpoint.

Yet, long before colonial maps inked modern borders, this land was home to the Mapuche and other indigenous groups—keepers of deep knowledge about Lanín’s moods. Their lives were interwoven with volcano, ice, and forest. To them, Lanín was more than a giant mountain; it was a spiritual entity, a locus of power, dangers, and reverence.

Ancient Giants: Geological Origins of Lanín Volcano

Lanín forms part of the Southern Volcanic Zone of the Andes, a segment along the western edge of South America where the Nazca Plate plunges steeply beneath the South American Plate—a process known as subduction. This collision crafts a theater of immense geological activity over millions of years, birthing fiery peaks like Lanín.

The volcano’s formation began in the Pleistocene epoch, with eruptions building its stratovolcano cone through successive layers of lava, ash, and volcanic debris. By the 19th century, Lanín was a venerable giant, its slopes cloaked in glaciers and its summit resting in perpetual chill, yet harboring the potential for violent awakening beneath.

The Calm Before the Storm: Pre-1826 Conditions and Indigenous Knowledge

The early 1800s were marked by relative geological silence at Lanín. According to indigenous oral histories, the volcano had long slept, with only minor tremblings whispered through the earth. Members of the Mapuche regarded the dormant mountain with a mixture of respect and cautious apprehension—prayers and rituals for peace were common in villages nearby.

European settlers and explorers arriving at dawn of the century noted lanscapes that seemed eternal: forests blanketing volcanic soil and the distant white peak of Lanín towering benignly. Yet, subtle signs began to amass—faint ash odors on the breeze, mild seismic tremors unseen but heard in local lore.

Sparks in the Silence: Early Signs of the Eruption

The first rumblings that heralded Lanín’s 1826 eruption arrived like muted warnings, felt before seen. Villagers recall nights when the earth trembled faintly beneath their feet, fires flickered oddly in the hearths, and animals grew restless.

Historical sources reveal that by the first months of 1826, a sequence of small volcanic earthquakes disturbed the region, unsettling residents on both sides of the border. Perhaps most tellingly, a faint plume of smoke was first observed rising above Lanín’s summit—a slender, ghostly column, barely visible against the pale sky.

This quiet prelude tore open swiftly, as the volcano shifted gears from slumber to a volatile awakening.

The Earth Trembles: The First Explosive Phase

In late 1826, the volcano’s roar escalated violently. From a distant horizon, a brilliant orange glow pierced the twilight, soon followed by thunderous blasts that shook the Andes like divine cannon fire. The eruption erupted in a series of explosive events that shattered the tranquil landscape.

Witnesses described incandescent bombs hurled skyward, while shockwaves rattled wooden homes and splintered forests. The mountain’s peak became a frothing cauldron spewing ash clouds thousands of meters high. An eerie apnea descended over the region as the deafening continuous rumble created an oppressive atmosphere.

Rivers of Fire: Lava Flows and Pyroclastic Surges Beyond the Summit

Lanín’s molten fury descended its flanks, rivers of incandescent lava snaking slowly but inevitably through fir forests and ravines. These flows consumed vegetation and reshaped the surrounding terrain, carving new valleys and obliterating old growth in their path.

Simultaneously, pyroclastic surges—deadly clouds of hot gas and volcanic fragments—rushed down slopes with terrifying speed, melting and incinerating everything. The sheer force was such that it isolated communities and destroyed trails, turning a once serene environment into a charred and turbulent wilderness.

Clouds of Ash and Sky Darkened: Atmospheric Impact and Eyewitness Accounts

Perhaps the most haunting aspect was the volcanic ash fallout. For days, the sky darkened not from dusk but from Lanín’s choking dust, painting towns and forests in dull grey. Crops failed under this sinister blanket, wells filled with gritty residue, and breathing became labored for those trapped beneath the ash clouds.

Local chronicles tell of skies turning crimson at sunset, unnerving even the most weathered frontiersmen. Birds ceased their songs, and for a brief, terrifying moment, it seemed as if the world itself held its breath beneath the volcano’s wrath.

Between Two Nations: The Shared Challenge for Argentina and Chile

The eruption unfolded during a formative era for both Argentina and Chile—newborn nations forging their identities after decades of colonial rule and independence conflicts. Lanín, sitting astride the border, became a symbol as well as a practical challenge.

Neither government possessed robust infrastructure to mount coordinated disaster responses in this wild frontier. Instead, indigenous communities and settlers relied heavily on traditional knowledge and mutual aid. The event underscored the porousness of borders in the face of nature’s might, a common threat transcending national rivalries.

Human Stories amidst Nature’s Fury: Indigenous and Settler Responses

The narrative of the eruption is incomplete without the human dimension. Mapuche elders spoke of sacred signs and renewal cycles, interpreting the eruption as both punishment and cleansing. Some villages evacuated to safer grounds, guided by ancient wisdom about wind patterns and past eruptions.

Settlers struggled with fear and confusion; many fled, others stayed to protect livestock and maintain settlements. Letters and journals from missionaries and soldiers provide heartfelt testimonies of hardship and solidarity. It is said that some of the most lasting bonds between indigenous and settler communities formed during this shared ordeal.

Mapping Disaster: Early Scientific Observations and Misinterpretations

European scientific understanding of volcanoes was still nascent in the early 19th century. Reports about Lanín’s eruption filtered slowly to urban centers, sometimes distorted by rumors or lack of precise data.

Geologists and naturalists dispatched to the region marveled at the scale, yet struggled to explain all phenomena with then-current volcanic theories. Some erroneously attributed the eruption to earthquakes alone, reflecting the era’s limited grasp on plate tectonics.

Nevertheless, these early expeditions laid groundwork for the birth of modern South American volcanology.

The Aftermath: Environmental and Ecological Transformations

When the eruption slowed and finally ceased, Lanín’s vicinity lay transformed. The scorched earth gave way, in time, to new animal migrations and colonizing plant species—nature’s slow but inexorable healing.

Wetlands formed from dammed rivers, alpine forests shifted patterns, and volcanic soils began enriching the land anew. This reshaping of ecosystems was a vivid example of the cycle of destruction and creation intrinsic to volcanic landscapes.

Political Consequences: How the Eruption Influenced Border Relations

At a time when Argentina and Chile were actively delineating their border regions, the eruption complicated territorial questions. The newly scarred environment was harder to map, and some communities found themselves isolated or on different sides of emergent boundaries.

But perhaps more profound was the eruption’s role as a shared challenge fostering early diplomatic dialogues concerning emergency aid and scientific collaboration—a foreshadowing of transnational environmental cooperation in Patagonia.

The Volcano in the Memory of Nations: Oral Traditions and Chronicles

Lanín’s 1826 eruption entered stories passed down across generations. Mapuche legends evolved to incorporate the event, portraying the volcano as a fire-spirit whose rage reshaped the earth and tested humankind’s resilience.

Meanwhile, Argentine and Chilean historians penned early chronicled accounts linking the eruption to burgeoning national identities. In public memory, Lanín became a symbol of raw nature’s grandeur and threat, a narrative that continues to inspire poets, artists, and scientists alike.

Lessons from Lanín: Early 19th-Century Volcanology’s First Test

The eruption served as a benchmark for South American volcanology. It highlighted the need for systematic observation, recognition of indigenous knowledge, and understanding of volcanic hazards in shaping settlement and economic patterns.

Though crude by today’s standards, the 1826 event’s documentation was invaluable for later researchers making sense of the region’s volatile geology.

Lanín’s Dormancy and Subsequent Activity: Tracing the Volcano's Later History

Following the 1826 eruption, Lanín settled once more into dormancy, punctuated by smaller events over the centuries. Modern monitoring records occasional seismic activity and fumarolic emissions, but nothing matching the fury witnessed nearly two centuries ago.

This pattern places Lanín among volcanoes with episodic eruptive histories—reminders that beneath a serene facade, powerful forces remain.

The Modern Legacy: Lanín in Science, Culture, and Conservation

Today, Lanín commands both scientific interest and cultural respect. It anchors Lanín National Park—a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve—and is an emblem of Patagonia’s untamed beauty.

Scientists leverage lessons from 1826 to assess volcanic hazards, while cultural preservation efforts honor indigenous traditions and commemorate the human stories woven around the mountain’s fiery heart.

Conclusion

The eruption of Lanín in 1826 was more than a geological event; it was a vivid chapter in the story of human endurance, cultural fusion, and scientific awakening in the shadow of nature’s raw power. It forced communities to confront vulnerability and adapt in ways that resonate through history—reminding us that the earth’s pulse beneath our feet is never truly silent.

Two nations divided by lines on a map were united by the mountain’s flame. The ashes that fell from the sky simultaneously scarred and enriched the land, symbolizing destruction and renewal hand in hand.

Lanín’s fiery awakening two centuries ago remains a testament to the intertwined fates of human and volcano, challenge and survival, memory and legacy.

FAQs

Q1: What caused the 1826 Lanín eruption?

The eruption resulted from magma rising due to subduction of the Nazca Plate beneath the South American Plate, which caused pressure buildup in the volcano’s magma chamber until it violently erupted.

Q2: How did indigenous people perceive the eruption?

The Mapuche and other indigenous groups saw the eruption as a spiritual event—a manifestation of the mountain’s power that was both a warning and a force of cleansing, deeply embedded in their cultural narratives.

Q3: Were there any casualties or significant damage?

While detailed records are scarce, the eruption caused substantial environmental damage, displacement of communities, and crop failures; however, specific casualty figures remain unknown due to limited documentation.

Q4: How did the eruption impact Argentina–Chile relations?

The eruption highlighted the cross-border nature of natural disasters, prompting some early cooperation and influencing border discussions during a formative period for both nations.

Q5: What role did the 1826 eruption play in volcanic science?

It was one of the earliest well-documented large eruptions in South America, helping spark scientific interest and observational efforts that contributed to the development of regional volcanology.

Q6: Is Lanín still active today?

Lanín remains an active volcano but has been dormant with only minor activity since 1826. It is continuously monitored for signs of future eruptions.

Q7: How is Lanín remembered culturally?

Lanín features prominently in indigenous oral traditions and national histories, symbolizing nature’s power and the resilience of local communities.

Q8: What lasting environmental changes resulted from the eruption?

The eruption reshaped local ecosystems by altering landscapes, creating new valleys and wetlands, and enriching soils through volcanic ash deposition, ultimately promoting ecological renewal.