Table of Contents

- The Dawn of Disaster: Morning of May 19, 1935

- Geography and Setting: Understanding Al Jabal al Akhdar

- Libya under Italian Rule: A Colony on the Edge

- The Seismic Sparks: The Earthquake's Origins

- First Shakes: Initial Tremors Felt Across the Region

- The Cataclysm Unfolds: The Full Force of the Quake

- Human Toll: Tragedy Strikes Villages and Towns

- Eyewitnesses Speak: Voices from the Rubble

- Colonial Authorities Respond: Crisis Management and Limitations

- The Role of Science in 1930s Seismology

- Aftershocks and Unrest: Shaken Land and Society

- Rebuilding amid Struggle: The Road to Recovery

- Mortality and Mourning: Cultural Practices Embed the Trauma

- Political Ripples: How the Earthquake Affected Italian Colonial Policies

- International Reactions: News Beyond Libya's Borders

- Lessons in Disaster Preparedness: Seismic Awareness in North Africa

- Legacy of 1935: Memory and Commemoration in Libya

- Comparing Catastrophes: The 1935 Earthquake in Historical Context

- Earth and Empire: The Intersection of Natural Disaster and Colonial Power

- Conclusion: Endurance, Memory, and the Shaken Land

- FAQs: Answers to Common Questions about the 1935 Libyan Earthquake

- External Resource

- Internal Link

The Dawn of Disaster: Morning of May 19, 1935

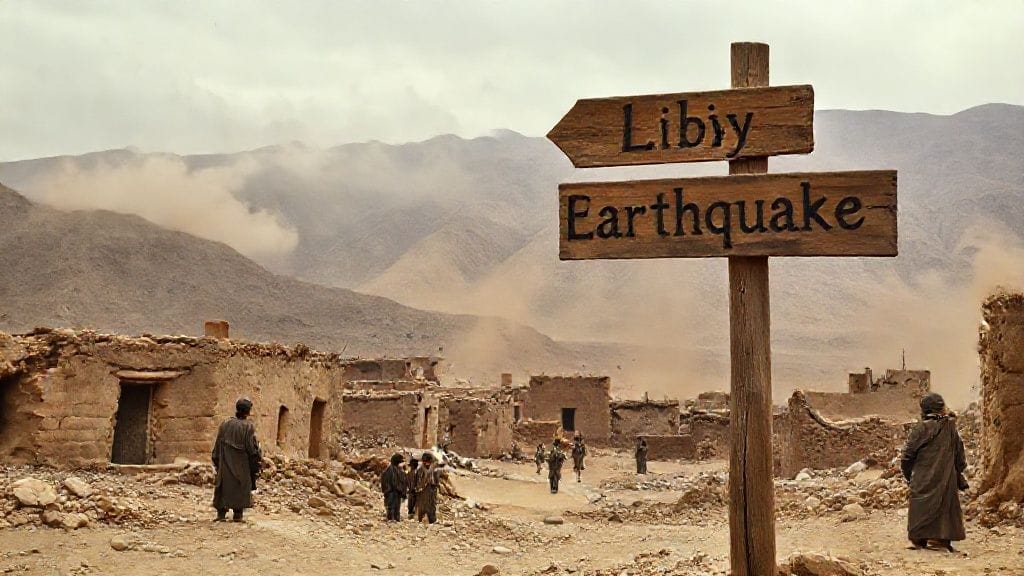

The sun rose over the rugged terrains of northeastern Libya, its golden rays casting long shadows over the olive groves and terraced hills of Al Jabal al Akhdar—the "Green Mountain"—a verdant oasis in an otherwise arid land. On the morning of May 19, 1935, the quietude was broken not by the sounds of daily life or the chirping of birds but by a trembling reverberation beneath the earth’s crust. In a matter of seconds, what had been a peaceful colonial outpost transformed into a cauldron of chaos and devastation.

It was a day destined to be etched in the memories of Libyans and the Italian colonial authorities alike—a day when nature’s fury exposed the vulnerabilities of a land under foreign dominion. Buildings crumbled, entire communities were shaken to their core, and hundreds lost their lives as the earth convulsed violently. Yet, beyond the tragic statistics lay stories of resilience, loss, and the interplay of natural forces with human history.

This is the story of the Al Jabal al Akhdar earthquake of 1935—the seismic event that forever altered Libya’s landscape and history.

Geography and Setting: Understanding Al Jabal al Akhdar

Al Jabal al Akhdar, known in Arabic as the “Green Mountain,” is a striking plateau region characterized by Mediterranean climate, fertile soil, and dense vegetation—a stark contrast to the surrounding desert expanses. Situated in Cyrenaica, modern-day northeastern Libya, this mountainous region rises dramatically from the coastal plains, offering elevations that can reach over 800 meters.

For centuries, its relative geographical isolation afforded the inhabitants a degree of protection and autonomy. Berber tribes and Arab settlers nurtured the fertile lands, cultivating olives, grains, and grapes. Small towns and villages clung to hillsides, their architecture blending with the natural contours of the terrain.

But this beautiful landscape sits at the crossroads of immense tectonic forces. The African and Eurasian plates converge in the Mediterranean basin, making northern Libya an area of occasional seismic activity, albeit infrequently catastrophic. The 1935 earthquake was a stark reminder of these buried tensions beneath the earth’s surface.

Libya under Italian Rule: A Colony on the Edge

To understand the human context of the earthquake, it is essential to grasp Libya’s political situation in the mid-1930s. Since 1911, Libya was an Italian colony, wrested from the Ottoman Empire after the Italo-Turkish War. The early years of colonial rule were marked by fierce resistance, especially from the Cyrenaican tribes under leaders such as Omar Mukhtar—a symbol of anti-colonial struggle.

By 1935, Italian control had consolidated, yet the scars of guerrilla warfare and repression lingered. Mussolini’s regime sought to transform Libya into a showcase of fascist colonial ambition, instituting infrastructure projects, agricultural development, and settlements intended to establish a “second Italy” across North Africa.

However, the region’s rugged terrain, mixed ethnic populations, and fragile economy presented constant challenges. The earthquake, striking amid this tension, compounded the hardships and exposed the limits of colonial governance in times of crisis.

The Seismic Sparks: The Earthquake’s Origins

The 1935 earthquake originated from a fault zone within the Cyrenaican massif. It was a shallow focus event, releasing energy suddenly along fault lines associated with the complex interaction between the African and Eurasian tectonic plates.

Seismographs in neighboring regions recorded significant tremors that morning, pinpointing a magnitude estimated between 6.5 and 7.0 on the Richter scale—a formidable force for an area not commonly known for powerful quakes.

The release of stress had been accumulating over decades, the geological tension finally snapping beneath the Green Mountain.

First Shakes: Initial Tremors Felt Across the Region

Before the main shock, residents reported mild tremors and strange sounds—a low rumble, like distant thunder emanating from beneath the earth. Many were caught unawares when the ground suddenly began to sway, buildings quivering as if caught in a violent breath.

In the larger town of Benghazi, located along the coast, windows rattled, and citizens spilled into the streets in panic. But it was in the villages nestled in Al Jabal al Akhdar where the earthquake’s full fury was soon to be realized.

The Cataclysm Unfolds: The Full Force of the Quake

At approximately 8:15 AM local time, the ground shook with an intensity that shattered stone dwellings and hurled rocks down the slopes. Entire walls collapsed in a cacophony of dust and screams.

Traditional mudbrick homes, typical of rural Cyrenaica, were particularly vulnerable. Landslides cascaded down the hillsides, burying fields and pathways, cutting off communication and access to isolated communities.

The shaking lasted around 30 seconds—a terrifying eternity. In its wake, the landscape was scarred: craters opened, trees were uprooted, and historic villages—some perched on ancient terraces—were reduced to ruins.

Human Toll: Tragedy Strikes Villages and Towns

Casualty estimates vary, but historians agree that hundreds perished in the disaster, with many more injured or displaced. Villages such as Al Qubbah and Derna experienced the heaviest losses. Families were devastated; survivors faced the bitter challenge of mourning loved ones amid the rubble.

The colonial administration struggled to assess the full scale of the tragedy. In many cases, accurate records were not kept or were underreported due to political considerations, but letters and testimonies reveal a landscape marked by grief.

Communities, already impoverished and strained under colonial rule, now confronted hunger, exposure, and disease that often followed natural disasters.

Eyewitnesses Speak: Voices from the Rubble

Accounts from survivors paint vivid and heartbreaking pictures. One villager, Ahmed al-Masri, recalled: “The earth groaned and carried away my father’s house like a child playing with a toy. We ran into the fields, but the dust swallowed our homes. It was as if the mountain itself had risen against us.”

Italian officials documented reports from engineers and doctors who described overwhelmed clinics and the desperate efforts to rescue trapped families. However, the colonial response was hampered by limited resources and mistrust between rulers and the indigenous population.

Colonial Authorities Respond: Crisis Management and Limitations

The Fascist Italian government dispatched military and civil units to the affected areas, proclaiming relief efforts and reconstruction plans. Emergency shelters were established, and medical teams worked tirelessly, sometimes under harsh conditions.

Yet, the response revealed systemic weaknesses. Roads damaged by the quake delayed shipments of aid; communication lines were disrupted. Furthermore, Italian authorities often prioritized colonial infrastructure and settler needs, leaving many Libyan victims marginalized.

The tragedy served as a stark mirror reflecting the inequalities embedded in the colonial system.

The Role of Science in 1930s Seismology

In the 1930s, seismology was an emerging science, with instruments becoming more precise and networks expanding. Italy, under Mussolini, invested in scientific research partly to bolster its grand narratives of modernity and control.

Seismograph readings from the 1935 earthquake contributed valuable data for Mediterranean tectonics, helping scientists understand fault behaviors and seismic risks in North Africa.

Nevertheless, scientific knowledge could do little to prevent the devastation in a region with inadequate building standards and emergency preparedness.

Aftershocks and Unrest: Shaken Land and Society

For weeks following the main quake, aftershocks rippled through Al Jabal al Akhdar. These secondary shocks, though smaller, perpetuated fear and hindered recovery. Communities hesitated to return to homes still standing precariously on cracked foundations.

The earthquake also exacerbated existing social tensions. Distrust between colonial authorities and Libyan natives deepened as complaints about unequal relief efforts circulated, sometimes sparking localized unrest.

In an already volatile political climate, the disaster underscored the fragility of peace.

Rebuilding amid Struggle: The Road to Recovery

Reconstruction began slowly. The Italian administration sought to showcase its capacity to restore order and modernize Libya. New buildings incorporated some seismic-resistant designs, and efforts were made to improve infrastructure.

Yet, many rural communities found themselves dependent on scarce resources, relying heavily on traditional methods to rebuild amid hardship.

The process of healing was not only physical but psychological—a slow mending of the social fabric torn by both natural disaster and colonial rule.

Mortality and Mourning: Cultural Practices Embed the Trauma

In Libya, as in many cultures, death rituals carry deep significance. Following the earthquake, families faced challenges performing rites as cemeteries were overwhelmed and the sheer volume of casualties strained community capacities.

Collective mourning became a vital expression of resilience. Stories of sacrifice and survival passed from generation to generation, embedding the earthquake’s memory within local consciousness beyond mere numbers.

Political Ripples: How the Earthquake Affected Italian Colonial Policies

The catastrophic event forced Mussolini’s regime to reconsider some aspects of governance in Cyrenaica. The damage revealed that infrastructural investments and administrative control were insufficient in addressing the needs of the territory.

The regime increased spending on public works and attempted to implement stricter building codes, framed as efforts to “civilize” and strengthen the colony.

However, these policies primarily served colonial interests, often sidelining the Libyan population’s needs and voices.

International Reactions: News Beyond Libya's Borders

Global news of the earthquake filtered slowly through diplomatic channels and press reports. While overshadowed by broader geopolitical tensions of the interwar period, the disaster did garner sympathy and sporadic offers of aid from neighboring countries and international organizations.

The event underlined the vulnerability of colonial possessions to natural forces and the limits of imperial control—a reminder to the world of the fragile nature of power.

Lessons in Disaster Preparedness: Seismic Awareness in North Africa

The 1935 earthquake highlighted serious gaps in disaster preparedness within Libya and North Africa generally. It spurred modest advances in seismic monitoring and emergency planning, though progress was uneven.

For decades, the event stood as a lesson in the need for integrating scientific understanding with social policy, particularly in regions vulnerable to tectonic hazards.

Legacy of 1935: Memory and Commemoration in Libya

Decades on, the Al Jabal al Akhdar earthquake remains a poignant chapter in Libyan history. Memorials in affected towns honor victims, and oral histories continue to circulate, melding the natural catastrophe with narratives of colonial struggle.

In post-independence Libya, the earthquake is sometimes evoked as a symbol of endurance—both of the land itself and the people who inhabit it.

Comparing Catastrophes: The 1935 Earthquake in Historical Context

Compared with subsequent earthquakes in the Mediterranean region, the 1935 quake was moderate in magnitude but significant in its human and political consequences.

It stands alongside other disasters that shaped regional history, such as the 1908 Messina earthquake in Italy, providing a comparative framework for understanding the interplay between geology and society.

Earth and Empire: The Intersection of Natural Disaster and Colonial Power

The Al Jabal al Akhdar earthquake illustrates a profound dynamic: nature’s unpredictable force colliding against the structures of empire.

While the earth does not discern political boundaries, the impact of disaster is inseparable from the social and political contexts in which it occurs. This catastrophe revealed the fragility not only of buildings but of colonial authority itself.

Conclusion: Endurance, Memory, and the Shaken Land

As the dust settled on Al Jabal al Akhdar in 1935, Libya faced an uncertain future. The earthquake was not simply a geological event but a turning point woven into the country’s colonial history.

The survivors’ stories, the struggle to rebuild, and the lingering scars—both physical and psychological—remind us of the intimate connection between human societies and the volatile planet they inhabit.

In reflecting on this calamity, we find resonances far beyond Libya’s borders: the universal vulnerability before nature’s might and the enduring human spirit determined to rise again, even from the ruins.

FAQs

Q1: What caused the 1935 Al Jabal al Akhdar earthquake?

A1: The earthquake was triggered by tectonic movements along fault lines associated with the convergence of the African and Eurasian plates beneath northeastern Libya, releasing accumulated geological stresses.

Q2: How severe was the earthquake in terms of magnitude and damage?

A2: It measured approximately 6.5 to 7.0 on the Richter scale, causing widespread structural damage, particularly to rural villages built with vulnerable mudbrick architecture, and resulted in hundreds of casualties.

Q3: How did the Italian colonial authorities respond to the disaster?

A3: They dispatched military and medical teams to affected areas and initiated relief and reconstruction efforts. However, these were often insufficient and unevenly distributed, reflecting broader colonial inequalities.

Q4: What was the impact of the earthquake on the local Libyan population?

A4: Besides the immediate loss of life and destruction of homes, many faced displacement, food shortages, and disruptions to traditional ways of life, compounded by social and political tensions under colonial rule.

Q5: Did the earthquake influence Italian policies in Libya?

A5: Yes, it prompted increased infrastructure investment and attempts to impose modern building regulations, though these primarily served colonial interests rather than the wellbeing of the Libyan populace.

Q6: How is the 1935 earthquake remembered in Libya today?

A6: It is remembered as a tragic yet pivotal event, commemorated through memorials and oral histories that emphasize resilience, and often framed within the larger narrative of colonial resistance and survival.

Q7: How did the scientific community benefit from studying this earthquake?

A7: The seismic data helped improve understanding of Mediterranean tectonics and contributed to the early development of seismology in North Africa, though practical applications in disaster preparedness were limited at the time.

Q8: Are there ongoing seismic risks in the Al Jabal al Akhdar region?

A8: While the region is seismically active, major earthquakes remain relatively rare. However, ongoing monitoring and preparedness are essential given the area's geology and population density.