Table of Contents

- The Twilight of a Caliphate: Damascus, Summer of 680

- Muʿawiya I: From Rebel Governor to Supreme Leader

- The Shifting Sands of Power: The Early Umayyad Ascendancy

- Damascus, the Pulsing Heart of the Umayyad Caliphate

- The Last Days of Muʿawiya I: An Aging Caliph in a Changing World

- A Kingdom in Tension: Factionalism and the Succession Question

- The Role of Yazid: Crown Prince and Controversial Heir

- The Final Illness: Damascus Watches and Waits

- Death in the Levant: The Passing of a Political Titan

- Immediate Reverberations: Damascus and Beyond

- The Succession Dispute Ignites: Seeds of the Second Fitna

- The Martyrdom of Husayn and the Shaping of Shi’a Identity

- Umayyad Consolidation or Fragmentation? The Post-Muʿawiya Era

- Political Innovation and Autocracy: Muʿawiya’s Enduring Legacy

- The Cultural and Religious Impact of Muʿawiya’s Rule

- Damascus after Muʿawiya I: The City that Witnessed History

- Reflecting on Power: Leadership and Legitimacy in Early Islam

- Historical Perspectives: Chroniclers, Poets, and Memory

- The Resonance of 680: How Muʿawiya’s Death Echoes Today

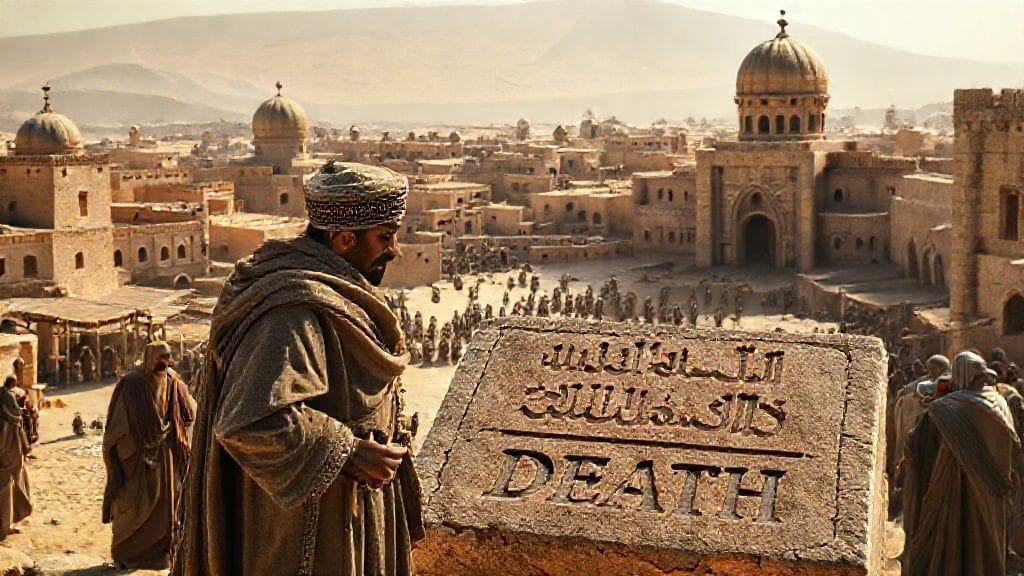

In the heat of a late summer afternoon in 680 AD, shadows lengthened over the ancient city of Damascus. The streets hummed with their usual rhythms: merchants bargaining in the bustling bazaars, call to prayers ascending from the minarets, children chasing one another through stone alleyways. Yet, beneath this veneer of daily life, a subtle, mounting tension gripped the city. The great caliph Muʿawiya I, the first ruler of the Umayyad dynasty and architect of a new political order, was nearing the end of his earthly journey. His breath, once as steady as the pulse of the caliphate he commanded, now faltered, and with it, the fate of the Islamic empire seemed to hang in precarious balance.

Muʿawiya’s death would not simply mark the passing of a man—it heralded the twilight of an era, the simmering of political rivalries, and the genesis of conflicts that would scar the Muslim world for generations. This moment in Damascus was one of quiet portent, a city and empire on the cusp of transformation, caught between the past’s faded glories and the uncertain dawn of new powers.

To understand the magnitude of Muʿawiya’s demise in 680, one must first journey through the turbulent currents that had carried him from humble beginnings to unparalleled sovereignty—an odyssey defined by ambition, pragmatism, and an unflinching grip on authority under the banner of Islam.

Muʿawiya ibn Abi Sufyan was not born to rule an empire; he was born into the prominent Quraysh tribe of Mecca, in an age when Islam was still tender and fragile as a sprouting seed. From the early days, Muʿawiya’s life was intertwined with the dramatic upheavals that shaped the Muslim community. Initially an opponent of the Prophet Muhammad, he famously converted to Islam only after the triumphant conquest of Mecca in 630 AD. The man who would become caliph was thus a figure of transformation himself—shaped by the convergence of tribal politics, religious passion, and the unrelenting expansion of a fledgling empire.

His career soared when, under Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab, Muʿawiya was appointed governor of Syria, a position he wielded with deft political acumen and military skill. Syria, a crucial province at the heart of the Near East, became his power base. This region was rich with Byzantine legacies, diverse populations, lingering paganisms, and growing Christian communities—all subject to the sharp strategy of a governor with a vision.

When the first Islamic civil war erupted, following the assassination of Caliph Uthman in 656, Muʿawiya rose as the champion of order and stability. Waging a protracted and bloody conflict against the fourth caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib, he would eventually establish himself as the undisputed caliph in 661, founding the Umayyad dynasty with Damascus as its gleaming capital.

The unity of the early Muslim community had fractured under his watch, but Muʿawiya’s rule introduced a new kind of political pragmatism—governance through centralized authority, diplomatic sophistication, and the integration of non-Muslim populations under Islamic rule. The caliphate under Muʿawiya became not only a religious leadership but also a complex bureaucratic state, drawing on the sophisticated administration of the Byzantines and Persians.

Damascus flourished as the empire's nerve center—the pulse of a realm stretching from the Arabian deserts to the eastern Mediterranean. Here, in its white stone palaces and winding streets, court ceremonies displayed the ritual of power, as Muʿawiya forged alliances, secured borders, and wielded statecraft with an iron yet measured hand.

Yet even at the height of his authority, cracks were visible. Muʿawiya’s choice of successor—his son Yazid—was a controversial break with earlier caliphal traditions of election or consensus. This dynastic ambition stirred unease and opposition, especially among those who favored the family of Ali or upheld the ideals of earlier caliphs. The succession question would prove to be the caliph’s final political battleground.

In the summer of 680, as Muʿawiya’s health deteriorated, the city of Damascus held its collective breath. The streets quieted, courtiers whispered anxiously, and poets composed elegies that mingled admiration with trepidation. The caliph’s death was not only a personal loss for his clan but also an omen for the empire’s future.

When his death was finally announced, the reverberations were immediate and profound. Yazid’s accession sparked rebellions, most famously led by Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad, whose martyrdom at Karbala would sear the Muslim conscience and deepen the sectarian divides still resonant today.

Damascus, once the shining jewel of the caliphate, became the stage upon which the tragic and violent drama of early Islamic history unfolded. Muʿawiya’s passing marked both the end of a dynasty’s meteoric rise and the beginning of internal strife that questioned the very foundations of Islamic governance.

Muʿawiya’s legacy is a mirror reflecting the complexities of leadership, faith, and power. He was a builder and breaker, revered and reviled. His reign advanced the political institutions of the caliphate, but his succession policies sowed discord. The memory of his death in Damascus serves as a poignant reminder of how history pivots on moments of loss and change, shaping identities and conflicts through centuries.

As the sun set behind the minarets in 680, Damascus mourned its caliph but also braced for the storms to come—forever imprinted with the echoes of a ruler whose life and death helped define an epoch.

Conclusion

Muʿawiya I’s death in 680 was far more than a mere historical footnote; it was a fulcrum of transformation, tragedy, and political evolution in the early Islamic world. His life story reads like an epic: from tribal scion to empire-builder, his visions and decisions set the course for the Umayyad caliphate and beyond. Yet, with his passing in Damascus, the fragile edifice of unity he had erected began to fracture, and the reverberations of his rule—and, crucially, his succession plan—sparked conflicts that would echo through Muslim history.

The city of Damascus, cradled in the heat of that fateful summer, bore silent witness to a turning point. The end of Muʿawiya’s era did not mean instability as an abstract concept but the eruption of real human passions, loyalties, and wounds. His story invites us to reflect on the nature of leadership, the challenges of legacy, and the often-painful birth of political order. It remains a vivid chapter in the human saga of power and belief, a testament to the enduring interplay of history and memory.

FAQs

1. Who was Muʿawiya I, and why is he significant in Islamic history?

Muʿawiya I was the founder of the Umayyad dynasty and the first caliph from this family line. His reign marked a shift toward dynastic monarchy and introduced new political structures that shaped Muslim governance. He is significant for consolidating Muslim rule in Syria and expanding the caliphate’s reach.

2. What were the circumstances of Muʿawiya’s death in Damascus?

Muʿawiya died in the summer of 680 AD after a period of illness. His death took place in Damascus, the capital of the Umayyad Caliphate, where he had ruled for nearly two decades.

3. How did Muʿawiya’s succession plan contribute to future conflicts?

Muʿawiya named his son Yazid as successor, breaking with earlier traditions that favored consultation or election. Yazid’s accession was contested, especially by supporters of Ali’s family, leading to uprisings and the Second Fitna, a major Islamic civil war.

4. Why is the death of Muʿawiya linked to the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali?

Husayn’s rebellion against Yazid’s rule culminated in his death at Karbala shortly after Muʿawiya’s death, symbolizing resistance to Umayyad authority and shaping the emergence of Shi’a Islam.

5. What role did Damascus play during Muʿawiya’s reign and after his death?

Damascus was the administrative and political heart of the Umayyad Caliphate, where decisions were made and the caliphate’s authority was exercised. After Muʿawiya’s death, it remained central to the unfolding political struggles.

6. How do historians view Muʿawiya’s legacy today?

Historians see Muʿawiya as a complex and pragmatic leader whose policies laid foundations for a new imperial model. While admired for his political skill, his reign is also scrutinized for initiating dynastic succession and sectarian divisions.

7. What was the Second Fitna, and how is it connected to Muʿawiya’s death?

The Second Fitna was a major civil war in the Islamic world triggered by disputes over Yazid’s succession, which followed Muʿawiya’s death. It involved multiple factions vying for power and legitimacy.

8. How did Muʿawiya’s death impact the cultural landscape of the early Islamic world?

Muʿawiya’s rule and demise influenced Islamic art, poetry, and religious thought, intertwining political authority with cultural expression. His death marked a moment of reflection and change in these domains.