Table of Contents

- The Tremor That Shook a Nation: May 5, 1930

- A Land on Edge: Historical and Geographical Backdrop of Myanmar

- Bago – The City at the Epicenter: A Portrait Before the Quake

- Silent Fault Lines: Understanding Myanmar’s Seismic Activity

- The Morning of May 5th: Witnesses to Catastrophe

- The Earth’s Fury Unleashed: The Course of the 1930 Myanmar Earthquake

- Buildings Crumble and Lives Shatter: Immediate Impacts on Bago and Beyond

- Human Stories Amid Rubble: Survival, Loss and Resilience

- Colonial Myanmar Under British Rule: Administrative and Social Context

- Responses in Chaos: Rescue Efforts and Emergency Relief

- Media Coverage and Public Awareness: The World Beyond Myanmar

- Scientific Investigations: Seismology in the Early 20th Century and Insights Gained

- The Aftershocks and Lasting Tremors: Psychological and Structural Legacies

- Rebuilding a City, Rebuilding Lives: Urban and Social Reconstruction

- The 1930 Earthquake in Myanmar’s Historical Memory

- How the Disaster Shaped Modern Seismic Policies in Myanmar

- Reflections on Vulnerability: Lessons from the Bago Earthquake

- Earthquakes and Empires: The Intersection of Natural Disaster and Colonial Governance

- The Quake’s Ripple Effects: Political, Economic and Cultural Consequences

- Commemorations and Memorials: Honoring the Past

- Contemporary Seismic Risk in Myanmar: Scientific and Societal Challenges

- Conclusion: Holding Memory in Tremulous Hands

- FAQs: Understanding the 1930 Bago Earthquake

- External Resource

- Internal Link

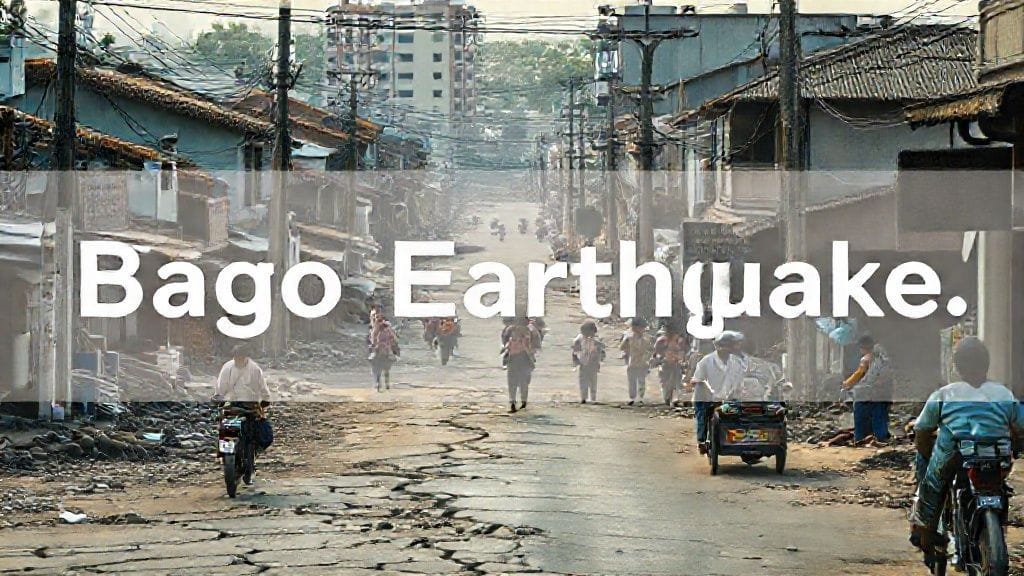

The ground began to pulse beneath their feet with an ominous rhythm—at first a subtle vibration, then a violent roar that ripped through the morning calm of Bago. On May 5th, 1930, what was an ordinary day in this Burmese city transformed into a nightmare as an earthquake struck—a seismic rupture whose tremors shook more than earth and stone; they unsettled the fragile mosaic of life beneath the British colonial rule. The air filled with dust and despair. Buildings, centuries-old pagodas, humble homes—all crumbled like sandcastles before a relentless tide of nature’s wrath. In the midst of chaos, lives were thrown into upheaval, communities shattered, and a country faced the brutal reminder of its place within the restless pulse of the earth’s crust.

This is the story of that event—the Myanmar (Bago) earthquake of 1930—not merely as a geological occurrence, but as a human drama etched into the landscape of time and memory.

A Land on Edge: Historical and Geographical Backdrop of Myanmar

To fully grasp the weight of the 1930 earthquake, one must step back to the geographic and historical stage upon which this tragedy unfolded. Myanmar, then known as Burma, was a land of great diversity nestled between the towering Himalayas and the sprawling Bay of Bengal. A land where rivers carved fertile plains and where ancient kingdoms once flourished. By the early 20th century, Burma found itself under British colonial governance—a situation fraught with tensions, ambition, and transformation.

Geographically, Myanmar lies on the complex boundary between the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates. The collision of these massive plates generates significant geological stress, leading to a network of fault lines threading through the region. The Sagaing Fault, running near Bago, is one of the most significant fault lines, infamous for generating destructive earthquakes.

Politically, the country was gripped by the dynamics of colonialism, with local populations navigating between traditions and the pressures of foreign rule. This tense societal fabric added layers of vulnerability and resilience as the earth began to shake.

Bago – The City at the Epicenter: A Portrait Before the Quake

Bago, situated in the fertile plains of Lower Myanmar, held a prominent position as a historic capital of past Burmese kingdoms. It was a city where pagodas touched the sky with golden spires reflecting sunlight and markets buzzed with the rhythm of daily life. In 1930, Bago was home to a mix of ethnic Burmese traditions and colonial influences.

Houses were built in traditional wooden style, interspersed by more solid British colonial administrative buildings. Pagodas and shrines dotted the urban landscape, reminders of Myanmar’s rich Buddhist heritage. The community was tight-knit but disparate in social strata—farmers, traders, colonial officials, monks, and artisans all weaving the fabric of city life.

Yet, beneath this vibrant surface lay precariousness. Buildings were often ill-prepared for natural disasters, and emergency infrastructures were minimal. This lack of preparation would soon become tragically apparent.

Silent Fault Lines: Understanding Myanmar’s Seismic Activity

While today Myanmar’s seismic threats are better understood, in 1930 scientific data was limited. However, the region's seismicity was no secret. The Sagaing Fault, a major strike-slip fault trending north to south, is analogous to California’s San Andreas Fault in its potential to unleash powerful quakes.

Local populations had folklore and empirical memory of tremors causing destruction. Still, modern seismological understanding was embryonic in this part of the world. Earthquake prediction was impossible, and the scientific equipment sparse.

The ominous tension beneath the landscape was a silent force awaiting release, invisible yet potent—a slow twist in the earth’s crust that culminated in the sudden violent event on May 5th.

The Morning of May 5th: Witnesses to Catastrophe

The dawn broke like any other but was soon shattered by the increasing groans of earth. Residents remember hearing deep rumblings and feeling the ground sway—some held onto pillars, others fled into the streets screaming.

One survivor recalled: "It was as if the heavens were tearing apart; the ground heaved beneath us; the pagoda bells rang dissonant and chaotic."

The quake’s initial shock lasted barely a minute, but it was enough to topple structures, crack earth, and send waves of panic through Bago’s population.

The Earth’s Fury Unleashed: The Course of the 1930 Myanmar Earthquake

The earthquake is estimated to have reached a magnitude of around 7.3 to 7.7, striking at approximately mid-morning. The intensity varied, but Bago felt the full force.

Seismic waves radiated south and north, affecting vast stretches of central Myanmar. Reports tell of aftershocks that lasted days, extending the sense of terror and compounding damage.

Rivers briefly changed course, landslides blocked roads, and dust clouds hovered over the city for hours after the initial tremor. The geographical disruption was immense.

Buildings Crumble and Lives Shatter: Immediate Impacts on Bago and Beyond

The destruction was widespread and brutal. Colonial buildings, despite stronger construction, were not immune. Pagodas, some centuries old, crumbled, their golden tiles shedding like autumn leaves.

Homes made of wood and bamboo were swept away or rendered uninhabitable. The death toll was significant, with official numbers estimated in the thousands, though precise counts remain uncertain. Injuries and displacement added to the human tragedy.

Local temples that housed relics and manuscripts were damaged, signaling not only a loss of human life but a cultural fracture.

Human Stories Amid Rubble: Survival, Loss and Resilience

Amid the devastation, stories of heroism, despair, and hope emerged. Families frantically searched for loved ones in the wreckage; neighbors pulled strangers from the ruins.

A Buddhist monk, preserved in eyewitness accounts, reportedly offered calm and guidance, helping survivors face the horror with spiritual strength.

But grief was widespread—orphans, widows, and the displaced struggled with the sudden void. Yet, the community’s capacity to come together revealed the resilience threading through the catastrophe.

Colonial Myanmar Under British Rule: Administrative and Social Context

In 1930, Myanmar was not an independent nation but a province of British India, administered remotely with a hierarchy of colonial officials.

This fact had consequences in the response to the earthquake. Communications often lagged, and resources for relief mobilization were constrained by bureaucratic layers and priorities of the British Empire.

Social tensions between Burmese locals and colonial rulers complicated the aftermath, as trust was scarce, and aid was uneven.

Responses in Chaos: Rescue Efforts and Emergency Relief

Local authorities, monks, and colonial officials scrambled to coordinate rescue, medical care, and shelter for the displaced. Medical supplies were limited; makeshift hospitals overwhelmed.

Relief caravans struggled with damaged roads. International aid arrived slowly or minimally, reflecting the period’s limited global disaster response infrastructure.

Despite hardships, networks of community solidarity flourished, laying early groundwork for organized humanitarian efforts.

Media Coverage and Public Awareness: The World Beyond Myanmar

News of the earthquake made ripples abroad. British newspapers reported on the scale of the disaster, though often framed within colonial perspectives.

Foreign journalists who reached Myanmar provided vivid testimonies, contributing to wider awareness but also sometimes reinforcing exoticized images of the “East in turmoil.”

The earthquake entered the global discourse on natural disasters but remained overshadowed by geopolitical events of the time.

Scientific Investigations: Seismology in the Early 20th Century and Insights Gained

Although seismology was still developing, the 1930 Myanmar earthquake became a case study for scientists studying the Sagaing Fault.

Seismographs, rudimentary yet vital, recorded data used to understand the fault’s behavior and regional hazard patterns. Efforts to map the fault line improved.

The quake underscored the need for better seismic monitoring in Southeast Asia—a call that echoed through later decades.

The Aftershocks and Lasting Tremors: Psychological and Structural Legacies

Aftershocks caused additional fear and destruction for weeks, preventing a swift return to normalcy.

Communities lived in tents or open areas, wary of collapsed buildings. Psychological trauma was profound, with stories of panic, sleeplessness, and lasting anxiety.

Structurally, many buildings were retrofitted or rebuilt with stronger materials, seeding an early awareness of earthquake-resistant architecture.

Rebuilding a City, Rebuilding Lives: Urban and Social Reconstruction

Reconstruction efforts began as soon as possible, balancing urgency with limited resources.

Traditional builders relied on community labor, integrating lessons learned. New administrative buildings incorporated emerging architectural principles.

Schools, markets, and cultural sites were restored or reimagined, embodying a communal determination to rise from the ruins.

The 1930 Earthquake in Myanmar’s Historical Memory

Over time, the great earthquake settled into Myanmar’s complex memory, overshadowed by political upheavals and later conflicts.

Still, in oral traditions, family histories, and local commemorations, the memory persisted as a somber chapter—reminding future generations of nature’s unpredictable force.

How the Disaster Shaped Modern Seismic Policies in Myanmar

Although limited immediately, the disaster eventually informed government approaches to natural hazards.

Modern Myanmar’s seismic risk management owes part of its foundation to early awareness forged in 1930.

Plans for urban development, emergency preparedness, and public education draw from lessons learned nearly a century ago.

Reflections on Vulnerability: Lessons from the Bago Earthquake

The earthquake exposed vulnerabilities in infrastructure, governance, and social systems.

It revealed the human cost when preparation is lacking. Yet, it also spotlighted resilience, community strength, and the necessity of integrating scientific knowledge into societal safeguards.

A timeless reminder that human hands must respect the restless earth beneath.

Earthquakes and Empires: The Intersection of Natural Disaster and Colonial Governance

Natural disasters during colonial rule often highlighted tensions between indigenous populations and imperial powers.

In Myanmar, the 1930 earthquake exemplified these dynamics—where aid was intertwined with politics, and disaster management reflected broader colonial hierarchies.

This intersection offers crucial insights into how empires responded to crises on the margins.

The Quake’s Ripple Effects: Political, Economic and Cultural Consequences

The earthquake’s devastation slowed economic activity in the region, disrupted trade routes, and strained colonial finances.

Politically, it acted as a catalyst for some demands for better local governance and infrastructure.

Culturally, the loss of sacred sites and relics deepened the poignancy of the event in Burmese identity.

Commemorations and Memorials: Honoring the Past

Though few large monuments exist, local memorials and annual remembrances preserve the quake’s memory.

Storytelling, Buddhist rituals for the dead, and community gatherings continue to honor the victims and survivors.

They offer collective mourning and affirmation of survival.

Contemporary Seismic Risk in Myanmar: Scientific and Societal Challenges

Today, Myanmar remains highly vulnerable to earthquakes. Urbanization has increased exposure; climate and environmental challenges compound risks.

Scientific institutions strive to expand monitoring, and NGOs work towards community education.

But poverty, political instability, and infrastructural weaknesses remain obstacles.

Conclusion: Holding Memory in Tremulous Hands

The Myanmar (Bago) earthquake of 1930 stands as a testament to the fragile balance between human aspiration and nature’s indomitable power. Its tremors shook more than earth—they shook societies, hearts, and histories.

Yet, within the rubble and ruin, the pulse of resilience beat strong. Communities rebuilt, memories sustained, and lessons passed on.

In remembering this event, we honor the lives forever changed and heed the call to live in harmony with a volatile earth—a challenge that remains as vital today as it was nearly a century ago.

FAQs

Q1: What caused the Myanmar (Bago) earthquake of 1930?

The earthquake resulted from a rupture along the Sagaing Fault, a significant tectonic boundary between the Indian and Eurasian plates. The fault’s motion accumulated strain until it released suddenly as a powerful earthquake.

Q2: How many people were affected by the earthquake?

Exact numbers are uncertain due to limited records, but estimates suggest thousands were killed or injured, and many more displaced, with major impacts focused in Bago and surrounding areas.

Q3: How did colonial rule influence the disaster response?

British colonial administration centralized authority but often caused delays and uneven aid distribution. Social tensions between locals and colonizers complicated coordination and trust during relief efforts.

Q4: What was the significance of the earthquake for seismology in Myanmar?

The 1930 quake provided critical data for early seismological studies of the Sagaing Fault, raising awareness of Myanmar’s earthquake risks and informing future monitoring and preparedness.

Q5: Are there memorials commemorating the earthquake today?

While no major national monument exists, local communities observe commemorations and maintain oral histories that honor the victims and acknowledge the event within cultural memory.

Q6: How has the earthquake influenced modern disaster management in Myanmar?

The event underscored the need for seismic-resilient infrastructure, emergency planning, and public education, influencing gradual improvements in Myanmar’s disaster preparedness policies.

Q7: Did the earthquake trigger political or social changes?

The disaster exposed infrastructural weaknesses and colonial governance limitations, fueling calls for better local administration. It also became a symbol of vulnerability and resilience within Burmese society.

Q8: What lessons does the 1930 earthquake offer for today?

It teaches the vital importance of preparedness, scientific study, community solidarity, and respect for nature’s unpredictable forces—a message echoing amid ongoing seismic risks in Myanmar.