Table of Contents

- The Twilight of Carolingian Hegemony: A Europe in Flux

- Rome’s Sacred Authority Meets Imperial Ambitions

- The Origins of Papal–Imperial Rivalry: A Tangled Web

- East Francia Emerges as the New Power Broker

- The Struggle Over Investiture: More Than a Ceremony

- The Role of the Papacy in Late 9th Century Politics

- The Fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire and Its Consequences

- The Popes of the Late 9th Century: Guardians or Politicians?

- Louis the German and the East Frankish Kingdom’s Assertion

- The Battle for Rome: Military and Diplomatic Maneuvers

- The Iconography of Power: Crosses, Crowns, and Keys

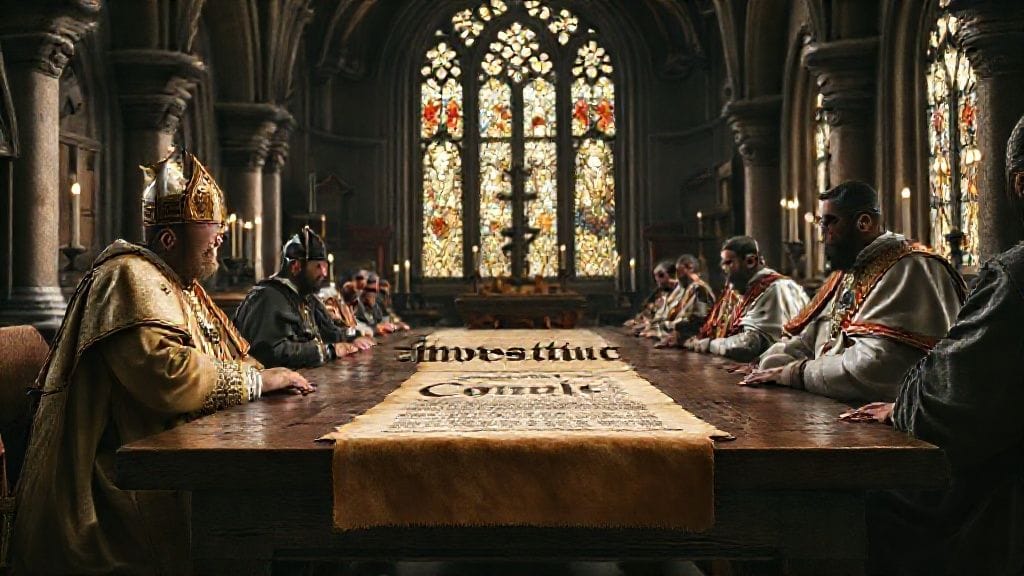

- The Lay Investiture Controversy: Seeding a Future Clash

- Faith and Power: The Intertwined Destinies of Church and Empire

- The Role of Local Nobility and Clergy in the Struggle

- The Shadow of Byzantium and the Eastern Empire

- The Transformation of the Papal State: From Spiritual to Temporal Power

- The Legacy of the Conflicts in Shaping Medieval European Politics

- The Human Dimension: Personalities and Anecdotes

- How the Conflicts were Recorded and Remembered

- Conclusion: The Foreshadowing of a Millennium-long Struggle

- FAQs: Understanding the Papal–Imperial Conflicts of Late 9th Century

- External Resource

- Internal Link

The Twilight of Carolingian Hegemony: A Europe in Flux

The late ninth century was a volatile epoch, a stage where the ancient order was disintegrating even as new forces clashed over the reins of power. Europe, fractured by familial feuds and external threats, watched uneasily as old loyalties wavered. Central to this grand drama was the city of Rome—its marble walls and ancient basilicas standing as silent witnesses to a battle not only for territory but for the soul of medieval Christendom. The papacy, embattled and yet unyieldingly sacred, faced the growing might of the East Frankish kings, heirs to Carolingian ambition and the Frankish dream of empire.

On the eve of the millennium, the conflict between the papacy and the imperial power was brewing—not yet the famous Investiture Controversy of later centuries, but the early, formative confrontations that would mark the medieval world for generations. This was a time when the right to appoint bishops—the spiritual nodes of power scattered across Christendom—was not simply religious prerogative but a cornerstone of political control. And so began a saga of intrigue, allegiances, and power struggles—one whose reverberations would echo long into the future.

Rome’s Sacred Authority Meets Imperial Ambitions

Rome had long since transcended being merely a city. Since the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the bishop of Rome—the pope—had come to claim spiritual supremacy over Christendom. By the ninth century, the papacy was no longer just a religious office but a claimant to a unique temporal authority, with its own territorial ambitions and military defenses. Yet, this claim frequently collided with those of the Carolingian emperors, whose drive to unify Europe under a Christian empire was often at odds with the papal agenda.

It was a delicate balance, one nurtured by legends of divine sanction, ancient imperial titles, and the Allfather’s blessing bestowed on Charlemagne just over a century earlier. The legendary coronation of 800 CE had set the precedent for emperor–pope cooperation, but also planted seeds of rivalry. The pope crowned the emperor, granting sacred legitimacy, but with this sanctification came expectations, claims, and contradictions.

By the late ninth century, as the Carolingian Empire fractured into several kingdoms, this balance began to shift. East Francia, ruled by the descendants of Louis the German, sought to assert control over Rome and its path to imperial destiny. The papacy, uncertain yet resolute, had to navigate a labyrinth of diplomacy, coercion, and at times, armed conflict to preserve its autonomy.

The Origins of Papal–Imperial Rivalry: A Tangled Web

The rivalry was more than just a clash of egos or political ambition; it was a deep ideological contest about the nature of authority in Christian Europe. From the Carolingian Renaissance to the pragmatic politics of local Roman elites, and even to the Byzantine interplay in Mediterranean affairs, the layers of tension were complex.

Around 875, after the death of Emperor Charles the Bald, the unity of the empire imploded. His heirs could neither consolidate nor maintain control effectively. This fragmentation gave local powers, including the papacy, unprecedented breathing room—and thus new opportunities—and threats. In Rome, the papacy faced challenges from rival noble families and the increasing pressure from East Francia, which desired recognition and influence over the city—a gateway to imperial legitimacy.

The conflict was wrapped in the question of investiture—the formal appointment of bishops and abbots. Who should have the ultimate authority to invest these spiritual leaders? The emperor, as protector and ruler of Christian lands? Or the pope, as spiritual head of Christendom, guardian of the sacred?

East Francia Emerges as the New Power Broker

East Francia, primarily situated in present-day Germany, rose as a pivotal player during this period. Unlike the Western or Middle Frankish realms, East Francia was relatively more stable under the rule of Louis the German and later his sons. These kings sought to revive Carolingian imperial unity through alliance with the papacy—or through dominance over it.

The East Frankish rulers saw the papal seat both as a spiritual symbol and a political prize. Controlling Rome and its ceremonies could bolster their claim to imperial authority across a fragmented continent. Hence, they intervened in papal elections, mobilized armies to assert influence, and engaged in a complex dance of diplomacy thinly veiling their ambitions.

This period also witnessed the emerging role of the Germanic clergy who increasingly aligned with East Frankish interests, often clashing with Roman-born families who traditionally dominated city politics and the papal curia.

The Struggle Over Investiture: More Than a Ceremony

At first glance, the investiture—the ceremonial handing over of ring and staff to bishops—might seem a mere formality. Yet, it was profound. Given the intertwining of temporal and spiritual power, bishops controlled lands, levies, and resources. To appoint a bishop was to wield power over significant portions of both the church and the secular realm.

The papacy insisted that no secular ruler should impose bishops lest spiritual authority be corrupted or swayed by political interests. Meanwhile, the East Frankish kings argued that, as guarantors of Christian peace and order, they had the right to maintain influence over bishops to prevent disorder.

The latency of this conflict during the late ninth century crystalline as various popes and East Frankish monarchs confronted one another, setting foundational conflict lines for the monumental Investiture Controversy of the 11th and 12th centuries.

The Role of the Papacy in Late 9th Century Politics

The popes of this era, far from being secluded spiritual shepherds, were central figures in the storm of European politics. They acted as kingsmakers, vetoes, mediators, and sometimes warlords, defending their city-state and spiritual jurisdiction.

But the papacy was weak militarily and financially compared to emerging secular states. It often relied on external kings, like those in East Francia, to secure lines of defense. However, this created dependency and tension, as each side sought leverage over the other.

One memorable pontiff of the period, Pope Formosus (891–896), who would later be posthumously ‘put on trial’ in a macabre testament to this era’s political intrigue, epitomizes the high stakes of papal politics. His papacy echoed the vulnerability and assertiveness of the office, caught in a web of alliances and rivalries that shaped the entire region.

The Fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire and Its Consequences

The once-mighty empire forged by Charlemagne shattered through both external invasions and internal divisions. Kings fought for control, dividing lands among heirs in a fractious mosaic of power. This splintering left Rome and the papacy as significant independent players, capable of both negotiation and manipulation.

Without a strong central emperor who could impose order, Rome became a chessboard. Various Frankish kings, local Italian lords, and even the Byzantine Empire tried their hand at influence.

This fragmentation also heralded a long medieval epoch where local powers rose, and the imperial ideal became a contested dream, not a settled reality.

The Popes of the Late 9th Century: Guardians or Politicians?

In a world rife with fluctuating allegiances, popes were constantly forced to be diplomats and power-brokers. The papal throne was not merely a spiritual office but also a prize coveted by factions within Rome and beyond.

Popes walked a narrow tightrope between asserting spiritual independence and managing political survival. Their handling of relations with East Francia was marked by alliances one day and excommunication threats the next.

The intricate dance of loyalty, necessity, and principle defined their reigns, as they strove to protect the sanctity of their office while ensuring the survival of their position.

Louis the German and the East Frankish Kingdom’s Assertion

Louis the German, a grandson of Charlemagne, was a vital figure in the late ninth century. His reign established East Francia as a force to reckon with—a kingdom aspiring for more than just regional dominance.

Louis’s policies towards Italy and Rome were a mixture of diplomacy and force. He sought control over the papal appointment but also knew the spiritual prestige such control would confer.

His successors continued this approach, alternately supporting and undermining popes, displaying the complex loyalties that typified the era.

The Battle for Rome: Military and Diplomatic Maneuvers

Armies marched, cities fortified, and alliances forged and broken. Control over Rome was fiercely contested, where each faction understood that the city was the symbolic and practical key to imperial legitimacy.

The military campaigns of this era, though sometimes modest in scale compared to later medieval wars, were intense and carried immense significance. Control over strategic fortresses around Rome shifted hands, and diplomacy was employed by power players to outmaneuver rivals.

This tug-of-war was often mediated through papal legates and emissaries, who navigated complex webs of loyalties to safeguard their interests.

The Iconography of Power: Crosses, Crowns, and Keys

Symbols mattered enormously in the late ninth century. The papal tiara, the imperial crown, the keys of St. Peter—each represented claims, legitimacy, and competing ideologies.

When a pope crowned an emperor, it was a ritual laden with meaning; it declared divine sanction but also presupposed a hierarchical order. If the emperor tried to impose bishops unilaterally, it was a visual and practical challenge to papal supremacy.

These symbols shaped the mentalities of rulers and subjects alike, binding faith, tradition, and political power into a potent mixture.

The Lay Investiture Controversy: Seeding a Future Clash

Though the Investiture Controversy would only erupt fully in the 11th century, its roots were firmly planted in these late ninth-century conflicts. The arguments, tensions, and precedents established during this time informed the later disputes between emperors like Henry IV and popes such as Gregory VII.

This period was the crucible in which ideas about the autonomy of the church, the limits of royal power, and the rights to appoint spiritual leaders were hammered out, often in bitter conflict.

Understanding this foreshadowing is crucial to grasping the medieval church-state dynamics.

Faith and Power: The Intertwined Destinies of Church and Empire

This era underscored that faith and political power were inextricable in medieval Europe. The papacy's claims rested on spiritual authority, but ultimately it could not ignore worldly power.

Similarly, kings and emperors dressed their authority in religious terms to justify rule and enforce order.

The resultant dynamic was of both partnership and opposition, a bipolar relationship that would shape European history for centuries.

The Role of Local Nobility and Clergy in the Struggle

Beyond emperors and popes, local forces played crucial roles. Roman noble families, regional bishops, and monastic figures all acted in their interest, sometimes supporting the papacy, sometimes East Frankish rulers, or their own agendas.

This internal complexity added layers to the conflict. Papal authority was not absolute, and papal-imperial tensions were deeply entangled with local rivalries.

The Shadow of Byzantium and the Eastern Empire

While the West wrestled with its own conflicts, the Byzantine Empire loomed as a distant, though influential, power.

Though estranged theologically and politically from Rome, Byzantium saw itself as a Christian empire and often eyed Italy as a zone of influence.

This added a broader geopolitical dimension to the papal–imperial conflicts, as alliances and rivalries extended beyond the Alps and into the Mediterranean.

The Transformation of the Papal State: From Spiritual to Temporal Power

During this period, the papal office increasingly took on the characteristics of a sovereign ruler. The Duchy of Rome and the Papal States evolved into more tangible political entities, involving taxation, military defense, and governance.

This transformation was both cause and consequence of the conflicts with East Francia, as the popes sought independence from secular kingship while also needing allies.

The institutions and precedents established would reverberate throughout medieval European political formation.

The Legacy of the Conflicts in Shaping Medieval European Politics

Looking back, the late 9th century papal–imperial struggles were vital in setting the stage for the Middle Ages. They encapsulated the evolving balance between church and state and offered early models of negotiation, conflict, and compromise.

These events helped mold the ideologies that governed Europe, influencing kings, popes, and commoners alike for centuries.

The Human Dimension: Personalities and Anecdotes

Amidst these momentous events stand figures of striking passion, ambition, and faith. The dramatic story of Pope Formosus’s posthumous “Cadaver Synod,” where political enmities spilled grotesquely into history, is emblematic of the era’s turbulent spirit.

Kings and popes wrote letters, swore oaths, and broke promises. These human elements reveal a world where power was often as fragile as faith was fierce.

How the Conflicts were Recorded and Remembered

Medieval chroniclers and later historians preserved these events with varying perspectives. From the annals of Regino of Prüm to the letters of clerics, the struggles are captured not merely as dry facts but as drama suffused with moral and political lessons.

These records form the foundation of our understanding of an era where the sacred and the secular eternally intertwined.

Conclusion

The late ninth century’s papal–imperial conflicts were more than mere political squabbles—they were a crucible where medieval Europe’s defining dynamics were forged. In the shadow of crumbling empires and the rise of new kingdoms, the struggle over Rome and investiture was a battle over the very nature of power, faith, and legitimacy.

Yet, beyond the clash of crowns and keys lies a profound narrative about human ambition, spiritual conviction, and the fragile weaving of institutions that would come to define an age. These conflicts, often violent and fraught, sowed the seeds of future transformations, revealing how closely intertwined the sacred and the secular truly were in the heart of medieval Europe.

It is incredible to grasp how these struggles, though distant in time, resonate even now—as echoes of a world wrestling to define authority and meaning amid uncertainty.

FAQs

Q1: What caused the papal–imperial conflicts in the late ninth century?

The conflicts stemmed primarily from competing claims over spiritual and temporal authority, especially regarding who had the right to appoint bishops and control Rome. The fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire further exacerbated these struggles.

Q2: Why was investiture such a contested issue?

Investiture symbolized the power to consecrate spiritual leaders who controlled significant lands and political influence. Control over investiture meant controlling both church and state mechanisms.

Q3: Who were the key figures involved in these conflicts?

Important figures include East Frankish kings such as Louis the German, and popes like Formosus. Additionally, local Roman nobility and clergy played crucial roles.

Q4: How did the fragmentation of the Carolingian empire influence these conflicts?

The division of the empire into smaller realms removed a strong central authority, allowing local powers like the papacy and East Francia to assert claims over Rome and challenge each other's influence.

Q5: Did the Byzantine Empire play a role in these conflicts?

While not directly involved in every conflict, Byzantium viewed Italy as an area of spiritual and political interest, influencing the broader geopolitical context.

Q6: How did these late ninth-century conflicts foreshadow the later Investiture Controversy?

They laid foundational questions and rivalries about church-state relations and the right to appoint bishops, setting the stage for the famous eleventh-century struggles.

Q7: Were these conflicts purely political, or were religious elements involved?

Both elements were deeply intertwined. Religious authority was a core component of political legitimacy, making these struggles as much about faith as power.

Q8: How did contemporary chroniclers and later historians interpret these events?

They recorded them as critical moments of moral, spiritual, and political lessons, often highlighting the frailty and complexity of both church and empire.