Table of Contents

- The Dawn of a Troubled Millennium: Europe on the Brink

- The Birth of the Truce of God: A Radical Call for Peace

- The Expansion of the Peace Movement: From Early Roots to Synods

- Aquitaine and Languedoc: Frontier of Contention and Conciliation

- Lords, Lords, and Warriors: The Fragmented Power Landscape

- The Role of the Church: Shepherding Souls Towards Peace

- Synods as Agents of Change: Formalizing the Truce of God

- The Mechanics of the Truce: Which Days Were Sacred, Which Were Not?

- Resistance and Compliance: How Warriors and Nobles Reacted

- Social and Economic Ripples: Peace and Its Consequences in Daily Life

- Women and the Peasantry: Unexpected Beneficiaries of the Truce

- The Expansion Beyond Southern France: Regional Variations and Adaptations

- The Relationship Between Peace and Truce of God and Feudal Justice

- The Legacy of the Truce: Paving the Way for Later Medieval Stability

- The Poetic and Cultural Reflections of the Peace Movement

- Did the Truce Really End Violence? Contradictions and Persistence

- The Synods’ Resolutions: Texts, Decrees, and Their Enforcement

- Comparisons with the Peace of God Movement: Continuity or Revolution?

- The Institutionalization of Peace: Church, Nobles, and the Crown

- The Decline and Transformation: How the Movement Evolved into the High Middle Ages

- Lessons for Modern Conflict Resolution: Medieval Experiments in Peace

- Conclusion: Why the Expanded Peace and Truce of God Still Speak to Us

- FAQs: Clarifying the Mystery of Medieval Peacemaking

- External Resource

- Internal Link

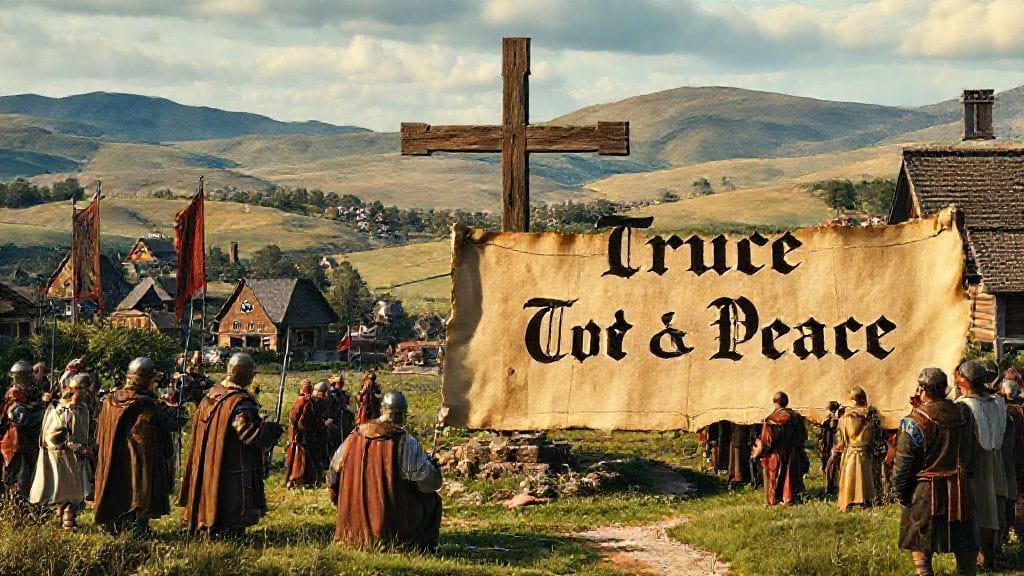

Europe, at the dawn of the second millennium, was a land of tremendous volatility. Dark, tangled forests shadowed humble villages; fortifications sprung up like fungal growth on the feudal landscape, and the clang of steel was a daily soundtrack for many. Yet, amidst this turbulence, something extraordinary took shape—an uneasy, fragile hope for peace. This hope crystallized in the medieval movement known as the Peace and Truce of God, a pioneering attempt to tame violence through faith and law. In the regions of Aquitaine and Languedoc, specifically, the movement grew in intensity and complexity, as Church synods formalized and expanded these fragile ceasefires, shaping the course of European medieval history.

The Dawn of a Troubled Millennium: Europe on the Brink

As the first light of the 11th century pierced the mist over the French countryside, Europe was still reeling from the collapse of Carolingian order. Fragmented authority birthed countless petty wars; noble families eyed each other across patchworked territories, ready to seize or defend their holdings by force. In Aquitaine and Languedoc, lands at the crossroads of cultures and claims, this feudal anarchism was particularly pronounced. Banditry, pillaging, and intermittent skirmishes plagued both peasants and knights alike. The Church, witnessing the unchecked bloodshed among Christendom’s own, began searching for solutions beyond the battlefield.

The Birth of the Truce of God: A Radical Call for Peace

The initial seeds of the Truce of God were sown in the late 10th century as bishops in southern France grew alarmed by the incessant warfare desecrating days meant for rest and worship. The idea was radical for its time: to prohibit violence during specific times—Sundays, feast days, and holy seasons—under penalty of excommunication. This notion confronted a culture where might often defined right. The Truce insisted that Christian warriors must, at the very least, honor sacred times, creating pockets of peace amid chaos. But this was more than a religious injunction—it was a daring social experiment to redefine honor and constraint among the powerful.

The Expansion of the Peace Movement: From Early Roots to Synods

What began as localized ecclesiastical decrees soon gathered momentum. Church leaders convened synods—councils of bishops and clergy—to codify, expand, and enforce these peaceful interludes. The 11th-century synods in Aquitaine and Languedoc were crucibles for this development, transforming informal calls for ceasefire into binding, if imperfectly observed, law. These assemblies represented the Church’s strategic mobilization to assert authority over secular violence, while appealing to shared Christian values. The synods' decrees grew increasingly detailed, encompassing not only days of enforced peace but also delineations of who could be targeted, and under what circumstances violence might be justified or condemned.

Aquitaine and Languedoc: Frontier of Contention and Conciliation

Nestled in the south-west and south of modern France, respectively, Aquitaine and Languedoc were vibrant cultural mosaics, influenced by Occitan culture and situated on vital trade routes. These regions were anything but peaceful—they suffered from frequent feudal rivalries exacerbated by ethnic and cultural complexities. The Truce and Peace of God held particular resonance here, partly due to the intertwined ecclesiastical hierarchy and local noble interests. Yet the enforcement of peace was no easy task in areas where warrior identity was deeply entwined with honor and territorial disputes. The synods in these regions, therefore, serve as illuminating case studies in the medieval negotiation of power, faith, and violence.

Lords, Lords, and Warriors: The Fragmented Power Landscape

Unlike centralized monarchies, southern France was characterized by a patchwork of petty lords, viscounts, and castellans, each jealously guarding their autonomy. The regional nobility were the principal actors in this narrative—both as perpetrators of violence and as reluctant participants in peace efforts. Their acceptance of the Truce and Peace of God was inconsistent and often opportunistic. Many were quick to proclaim allegiance to Church decrees when convenient, yet eager to resume hostilities once the sacred intervals passed. This delicate balance suggests the synods’ pragmatic role: less as enforcers and more as mediators attempting to channel noble ambitions into less destructive trajectories.

The Role of the Church: Shepherding Souls Towards Peace

At the heart of the Peace and Truce of God stood the Church, wielding spiritual authority as a tool for social control. Bishops and abbots framed their appeals in theological language: peace was not merely pragmatic but divinely mandated. The threat of excommunication—cutting a man off from the Church and eternal salvation—was a potent deterrent in an age where faith underpinned all aspects of life. Additionally, the Church offered not only spiritual sanctions but often mediated truces between conflicting parties, sometimes leveraging ecclesiastical lands as safe zones. Yet, their success was mixed, failing to fully end warfare but gradually embedding peace as a Christian value in medieval culture.

Synods as Agents of Change: Formalizing the Truce of God

Synods held in Aquitaine and Languedoc in the course of the 11th century illustrate the evolving institutional approach to peace. These councils gathered representation from the clergy, nobles, and sometimes even communal leaders. Here, the abstract ideals of peace were subjected to rigorous debate and codification. Decrees detailed the precise calendar times when combat was forbidden, defined who was protected (noncombatants, clergy, peasants, merchants), and established penalties for violations. The synods also addressed economic and social behaviors that fomented conflict, pushing for broader moral reform. Their decisions created a corpus of canon law intertwining faith and temporal order.

The Mechanics of the Truce: Which Days Were Sacred, Which Were Not?

The rules of the Truce of God were deceptively simple yet revolutionary. Violence was banned on Sundays and on important feast days such as Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost. During these intervals—sometimes stretching to several days—knights were expected to lay down arms. The Truce extended also to certain times of the agricultural calendar to protect planting and harvest seasons, critical for peasant survival. Violations were met with severe ecclesiastical punishments, though enforcement varied considerably. This rhythmic sanctification of time turned the medieval calendar into a tapestry alternating between sanctioned conflict and enforced peace, subtly reshaping medieval notions of violence and sanctity.

Resistance and Compliance: How Warriors and Nobles Reacted

The reaction of laïc powers to the Truce and Peace of God was complex. Some nobles embraced the movement, recognizing it as a means to reduce costly feuds and focus energies on legitimate warfare such as crusades or territorial expansion. Others resisted, viewing the Truce as an infringement on their martial freedom and honor. Anecdotes from chronicles reveal episodes where knights breached the peace under cover of darkness or disguised their campaigns as revenge or justice. Still, over decades, a slow cultural shift emerged. Even reluctant lords had to reckon with the growing ecclesiastical influence: breaking the Truce could isolate one politically and spiritually, an unacceptable risk in a tightly woven feudal mosaic.

Social and Economic Ripples: Peace and Its Consequences in Daily Life

For the peasantry and merchant classes, the Truce and Peace of God brought tangible though limited respite. During peaceful periods, markets thrived, travel became safer, and agricultural activity proceeded with less risk. This intermittent calm allowed for minor economic recovery in otherwise insecure rural environments. While the Truce could not prevent large-scale devastation, it created pockets of stability that sometimes enabled community resilience and modest prosperity. It also enhanced the Church’s role as both moral authority and protector, deepening its ties with local populations and conferring a new civic dimension to religious practice.

Women and the Peasantry: Unexpected Beneficiaries of the Truce

The synods’ peace initiatives, though primarily focused on martial classes, indirectly benefited women and peasants who were most vulnerable to the ravages of feudal warfare. Women often bore the brunt of pillaging, forced displacement, and the breakdown of social order. The Church’s emphasis on protecting noncombatants in synodal decrees provided them an unprecedented, if fragile, form of legal sanctuary. In some cases, monasteries and churches became refuges for women fleeing violence. These protections contributed subtly to the social fabric, enhancing notions of Christian charity and communal responsibility.

The Expansion Beyond Southern France: Regional Variations and Adaptations

While centered in Aquitaine and Languedoc, the Peace and Truce of God soon radiated northwards and beyond the borders of France. Its principles were adapted to local circumstances—from the Rhineland’s dense network of ecclesiastical princes to the fragmented British Isles. Each region modified the timing and scope of peace observance, revealing the movement’s flexibility. Yet, southern France remained the heartland not only because of its initial synodal decrees but also due to the region’s unique fusion of feudal fragmentation and vibrant ecclesiastical authority.

The Relationship Between Peace and Truce of God and Feudal Justice

The Peace and Truce of God arose in a world where justice was decentralized and often violent. Feudal justice was frequently enforced through personal retaliation and local warfare. The Church’s intervention introduced a layer of supra-local law, challenging the brute logic of vendettas. Though not replacing feudal justice, the Peace and Truce served as a framework for conflict limitation and arbitration. This embryonic legal consciousness would, over time, influence evolving medieval jurisprudence and the gradual development of more centralized authorities.

The Legacy of the Truce: Paving the Way for Later Medieval Stability

Though never eradicating war, the Peace and Truce of God planted seeds that shaped later medieval Europe. By proving that violence could be regulated through religious and social means, it laid an early blueprint for the rise of more centralized state powers and the consolidation of peace as a value. The movement also prefigured the Crusades’ spiritualized warfare and the growing role of canon law in secular governance. Its moral vision lingered in subsequent efforts to foster order amid medieval chaos, giving it a profound place in the cultural memory of Christendom.

The Poetic and Cultural Reflections of the Peace Movement

The influence of the Peace and Truce of God spilled into medieval literature and culture, particularly in the troubadour tradition of Aquitaine and Languedoc. Poets and minstrels wove themes of chivalry, peace, and justice into their works, echoing the region’s unique blend of martial and spiritual ideals. These cultural artifacts serve as testament to how deeply the movement penetrated not just political structures but the very imaginations of medieval people trying to reconcile violence with Christian ethics.

Did the Truce Really End Violence? Contradictions and Persistence

Critics and contemporaries alike questioned the efficacy of the Truce and Peace of God. Violence persisted, often erupting before or after sacred intervals, and enforcement varied wildly. Yet, to dismiss the movement as mere piety or church propaganda overlooks its subtle but vital role in molding medieval conflict. It introduced moral limits where none had been accepted before, created expectations of restraint, and framed peace as an attainable objective. In this light, the movement was not so much an end to war as an early attempt at its human regulation.

The Synods’ Resolutions: Texts, Decrees, and Their Enforcement

The written resolutions of the synods give us precious insight into the medieval mindset. Carefully crafted and solemnly proclaimed, these documents sought to codify peace with legal precision. They invoked scripture, ecclesiastical authority, and communal responsibility. Enforcement relied on a mix of public shaming, excommunication, and alliance with secular powers. Their survival in archives today enables historians to reconstruct the workings of medieval law-making and the vibrant interplay between faith and violence.

Comparisons with the Peace of God Movement: Continuity or Revolution?

The Peace of God, initiated in the late 10th century, was the forerunner focusing on protecting property, clerics, and peasants from marauding knights, while the Truce of God stressed temporal restrictions on violence. Together, they represent an evolutionary continuum in medieval peacemaking. Their interaction and overlap, particularly in southern France, highlight the dynamism of Church-led peace initiatives as responses to the outrageous violence of their times. Neither was a panacea, but together, they marked a spiritual and legal turning point.

The Institutionalization of Peace: Church, Nobles, and the Crown

Over time, as kings’ power grew, the Peace and Truce of God movement would be absorbed into emerging state structures responsible for law and order. The cooperation between Church councils and the nascent monarchies was crucial for institutionalizing peace beyond religious calendars. Aquitaine and Languedoc, with their complex feudal hierarchies, served as proving grounds for such cooperation. This institutionalization not only helped stabilize regions but also forged the medieval synthesis of spiritual and temporal authority central to European governance.

The Decline and Transformation: How the Movement Evolved into the High Middle Ages

By the 12th century, the specific contours of the Peace and Truce of God began to fade, transformed by new political realities and the rise of royal justice. The initial fervor evolved into more formal judicial processes and chivalric codes, reflecting changing ideas of war and peace. Nevertheless, the movement’s spirit persisted, informing crusading ideology and the medieval conception of just war. Understanding its decline offers insight into the fluidity of medieval institutions and the continual struggle to reconcile violence with Christian ethics.

Lessons for Modern Conflict Resolution: Medieval Experiments in Peace

Though distant in time, the Peace and Truce of God offers surprising lessons for modern peacemakers. It underscores the power of shared values, the role of symbolic time in social regulation, and the potential of non-state actors, particularly religious communities, in conflict mediation. Its partial successes and failures reveal the complexity of enforcing peace but also its necessity. This medieval experiment invites reflection on how moral authority, community involvement, and legal frameworks can work together even in fractured societies.

Conclusion

The Peace and Truce of God, expanded by synods in Aquitaine and Languedoc during the early Middle Ages, stands as a remarkable testament to human striving for order amid chaos. It was not a perfect peace, nor ever absolute, but rather a mosaic of hope, faith, and legal innovation in a violent era. The Church’s audacious attempt to sanctify time and limit violence reshaped medieval society in enduring ways, intertwining morality with governance and laying foundational stones for the eventual emergence of nation-states and modern law. To read its history is to witness a community’s effort to reclaim humanity in times of uncertainty—a story both distant and immediately resonant in today’s fractured world.

FAQs

Q1: What exactly were the Peace and Truce of God?

The Peace of God was a movement beginning in the late 10th century aimed at protecting noncombatants and church property from violence. The Truce of God followed as an extension, forbidding warfare on specific holy days and periods to limit fighting. Together, they were ecclesiastical efforts to regulate medieval violence.

Q2: Why were Aquitaine and Languedoc central to this movement?

These regions had fragmented political authority and frequent feudal conflicts, making the need for peace urgent. Their strong ecclesiastical structures also facilitated synods that formalized the movement's legal and spiritual rules.

Q3: Did these movements stop all violence?

No, violence continued intermittently. However, the Truce and Peace of God introduced moral limits and institutional frameworks that sought to reduce and regulate warfare in a period otherwise marked by chaotic violence.

Q4: What role did synods play in this process?

Synods were church councils that formalized the rules of the Peace and Truce, issued decrees, and attempted enforcement, transforming ecclesiastical moral calls into legal frameworks binding on Christian society.

Q5: How did secular lords react to these restrictions?

Reactions were mixed. Some nobles embraced the movement as a way to curb destructive feuds, while others resisted or manipulated it for political advantage. Over time, the Church’s authority compelled greater compliance.

Q6: In what ways did ordinary people benefit?

Peace initiatives helped protect peasants, women, and merchants from the harshest impacts of war. The sanctification of specific times allowed safer agricultural and economic activities and offered legal grounds for sanctuary.

Q7: How did the Peace and Truce of God influence later medieval governance?

They helped lay the groundwork for centralized justice systems by introducing supra-local legal norms, blending spiritual and temporal authority, and highlighting the necessity of regulated violence.

Q8: Is there a modern parallel to the Peace and Truce of God?

While contexts differ, the movement’s use of moral authority, community enforcement of peace, and partial conflict regulation find echoes in modern peacemaking, ceasefires, and conflict resolution efforts.