Table of Contents

- The Dawn of a New Vision: The First Photograph Emerges in France, 1826

- Joseph Nicéphore Niépce: The Inventive Mind Behind the First Exposure

- The Alchemy of Light and Chemistry: Early Photographic Experiments

- The View from the Window at Le Gras: Capturing Time itself

- The Technical Marvels and Challenges of the First Exposure

- A World in Shadows: Pre-photography Visual Culture and Its Limits

- The Role of France in the Birth of Photography: A Cultural and Scientific Hub

- Niépce’s Partnership with Louis Daguerre: The Path Toward a Revolution

- The Impact of the First Photograph on Art and Society

- The First Exposure’s Legacy in the Evolution of Camera Technology

- Photography as a New Language: Changing Perceptions of Reality

- Early Reception: Skepticism, Wonder, and the Seeds of Enthusiasm

- The Global Ripple Effects: How the First Exposure Transformed Other Nations

- Bridging Science and Art: The Photograph’s Dual Identity

- From Experiment to Industry: The Economic Consequences of Early Photography

- The Human Dimension: Stories of Those Who Witnessed the Birth of Photography

- Ethical and Philosophical Reflections: What Did It Mean to Capture Reality?

- The Enduring Mystery: Technical Debates About the Exact Methods Used

- The Preservation and Rediscovery of Niépce’s First Photograph

- Photography First Exposure and the Modern World: Continuities and Inspirations

- Conclusion: Reflections on the Power of the First Image Captured by Light

- FAQs: Answering Your Curiosities on the Photography First Exposure

- External Resource: Further Reading and Research

- Internal Link: Explore More at History Sphere

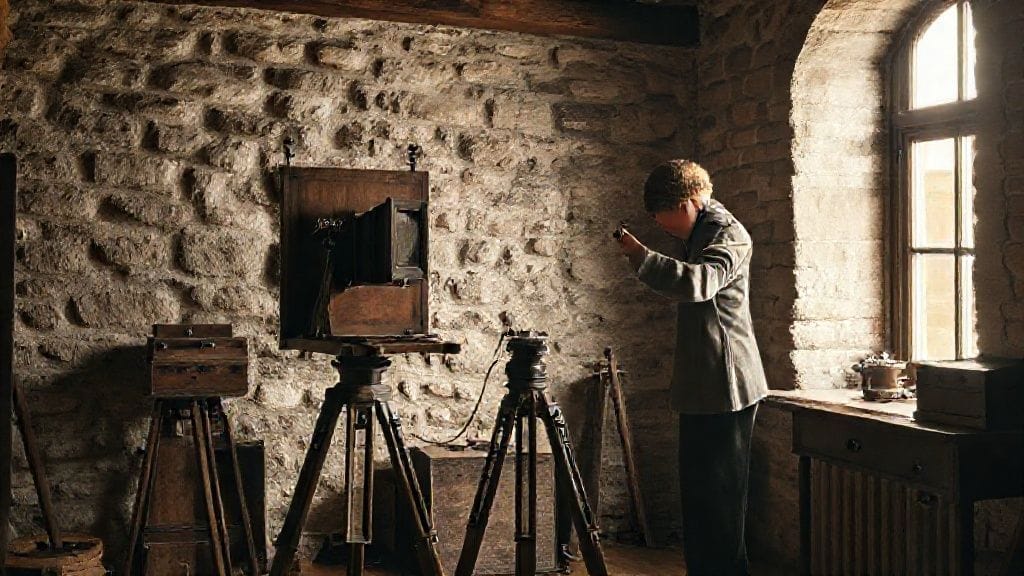

The year was 1826. Outside the sun cast gentle shadows over the quiet countryside of Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, in eastern France. Inside a modest stone house, a man peered anxiously through a contraption that looked more like alchemical machinery than anything one might recognize as a camera. He set the apparatus to capture what had never before been permanently trapped: the fleeting dance of light and shadow—an image made permanent. This moment, etched in obscurity for nearly two centuries, marks the monumental occasion known as the photography first exposure.

No one could yet grasp its enormity. Yet, in that still exposure—a view from Niépce’s window—time paused, history was rewritten, and the human eye gained a companion tool that would change art, science, and society forever.

The Dawn of a New Vision: The First Photograph Emerges in France, 1826

The birth of photography in 1826 France was not merely a technical feat. It was a profound cultural rupture—a collision between light, chemistry, and human curiosity. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s pioneering work intersected with a growing hunger for new methods to observe, document, and immortalize reality. The first photograph, known as View from the Window at Le Gras, was far from a perfect image. It was grainy, monochrome, and took hours of sun exposure to etch onto its pewter plate. But it marked something extraordinary: the harnessing of light to create a lasting imprint.

This harsh, blurred image opened doors to a new reality—a mechanical eye, precise and relentless, which did not rely on the frailties of human memory or interpretation. This new visual language would soon redefine how societies saw themselves, altering everything from portraits to journalism, from the sciences to the arts.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce: The Inventive Mind Behind the First Exposure

Niépce’s journey was one marked by persistence, curiosity, and a willingness to explore uncharted scientific terrains. Born in 1765, he was more than just an inventor—he was a poet of light. A man caught between the enlightenment ideals of reason and the Romantic desire to immortalize fleeting moments. His fascination with optics and chemistry drove him to experiment relentlessly, often in solitude and obscurity.

This is a tale not just of machines but dreams. Niépce’s meticulous developments in heliography—the process of capturing images through light-sensitive coatings—laid the foundation for the first permanent photograph. His story is also one of struggle: battling the technical limitations of his era, the skepticism of contemporaries, and even personal doubts. He never lived to see the full impact of his invention but planted the seed for a revolution.

The Alchemy of Light and Chemistry: Early Photographic Experiments

Before the first photograph’s successful exposure, the world was ripe with various attempts to physically capture an image. The camera obscura had been known for centuries, yet it was only an optical device projecting an ephemeral image onto a surface—not one that fixed the image permanently. The challenge was chemical: how to make light imprint upon a medium permanently, resisting the ravages of time.

Niépce’s early experiments utilized bitumen of Judea, a substance that hardened when exposed to light. Coating a pewter plate with this resin, he exposed it for around eight hours in the sun using a camera obscura setup. The areas exposed to the most light hardened, while the rest could be washed away, revealing an image etched in chemical relief.

This marriage of chemistry and optics was nothing short of alchemy for the time—the transformation of the intangible into the tangible, the invisible captured by a medium forever.

The View from the Window at Le Gras: Capturing Time itself

Imagine the scene: the worn stone window frames a slanted rooftop, a winding courtyard with trees and a barn in the distance. The light shifts slowly over the course of the long exposure, casting soft shadows that register as blurs in the delicate process. The pewter plate captures every nuance—the grain of the stone, the shape of the trees—but in a foggy, almost ghostly fashion.

This photograph, View from the Window at Le Gras, was more than an image. It was the first ever fixed exposure of a natural scene. The profound silence of the image contrasts sharply with the bustling life beyond the frame, forever frozen in an uncanny stillness.

The exposed plate took nearly a day in the sun to produce this image. Yet, what seems a technical limitation was a philosophical blessing: the resulting artifact embodies time’s passage, showing a slow dance of sunlight that human eyes cannot perceive in a glance.

The Technical Marvels and Challenges of the First Exposure

Niépce’s technique was a delicate balance of art and science, trial and error. The chemistry was unstable—bitumen was slow to harden and difficult to manage. The exposure times demanded patience and consistent sunlight, while the camera obscura itself had no focusing lens as we imagine today.

The plate’s preparation had to be immaculate. Niépce’s formula for the light-sensitive coating was a guarded secret, refined over years of painstaking experimentation. Moreover, developing the image took the positive and negative process out of the problem—Niépce’s method produced a sort of permanent relief on the plate but no direct negative that could be replicated.

The first photograph's grainy quality was not a flaw but a hallmark of the process's infancy. It speaks to a time when the world was only beginning to concede that the invisible forces of light could be mastered by human technique.

A World in Shadows: Pre-photography Visual Culture and Its Limits

It’s easy now to forget that before photography, humanity’s visual records depended on painting, drawing, and the written word. Portraiture was often reserved for the elite. Scenes of everyday life were curated through the subjective lens of artists, whose renderings inevitably bore personal interpretation, social ambitions, or patron preferences.

The camera obscura offered glimpses of reality but was limited to fleeting projections, ephemeral shadows lost once the viewer looked away. The idea of freezing a moment, preserving it with scientific exactitude, was a radical, almost heretical leap.

For centuries, artists struggled to capture “truth.” Now, with Niépce’s first exposure, a new standard was offered: mechanical fidelity, limited yet revolutionary, hinting at an objective vision of reality.

The Role of France in the Birth of Photography: A Cultural and Scientific Hub

Early 19th-century France was fertile ground for innovation. Political upheavals, shifts in social structure, and enlightenment ideals fostered a welcoming climate for experiments on the frontiers of knowledge and art. Scientific academies, salons, and the burgeoning middle class supported invention.

Intellectual circles mingled with artists and engineers, facilitating the cross-pollination that nurtured photography. Niépce’s region was a microcosm of this ferment, and the French government itself would later recognize the significance of the field.

Moreover, France’s cultural prestige meant that the image of the photograph carried weight beyond the scientific community—it was a statement about progress, modernity, and the power of human ingenuity.

Niépce’s Partnership with Louis Daguerre: The Path Toward a Revolution

Niépce’s work was the crucial first step, but the revolution of photography was far from complete. In 1829, Niépce entered into a partnership with Louis Daguerre, a talented artist and scenographer fascinated by visual effects and optics.

Together, they sought to improve the sensitivity and clarity of images, reduce exposure times, and develop practical methods for image reproduction. Niépce’s untimely death in 1833 left Daguerre to carry the torch alone, culminating in the daguerreotype process announced in 1839.

This partnership bridged intimate innovators’ pursuits with public spectacle, bringing photography from an obscure workshop to the center of global attention. It underscored that invention is rarely solitary—progress is collective and often collaborative.

The Impact of the First Photograph on Art and Society

Once the notion emerged that images could be mechanically captured, the art world and society at large grappled with immense transformations. Portraiture became democratized—no longer the province of nobles or the wealthy, individuals from broader social strata could now fix their visages for posterity.

Artists reacted in varied ways: some perceived photography as a threat, others embraced it as a new tool. Throughout the 19th century, painters incorporated photographic principles into their work, challenging traditions of realism and perspective.

Society, for its part, was fascinated but wary. The photograph embodied a promise of truth, yet it raised existential questions about reality’s representation, memory’s reliability, and the essence of human expression.

The First Exposure’s Legacy in the Evolution of Camera Technology

Niépce’s achievement laid the foundation for rapid advances in camera design and photographic chemistry. Subsequent inventors developed faster, more portable apparatuses; sensitive materials replaced bitumen; emulsions and glass plates enhanced image clarity.

The camera evolved from a cumbersome scientific contraption to a cultural instrument, accessible to amateurs and professionals alike. These advancements over decades culminated in the explosion of photography as both a scientific necessity and a popular art form.

The lineage from View from the Window at Le Gras to today’s digital cameras is a testament to relentless human curiosity and technological refinement.

Photography as a New Language: Changing Perceptions of Reality

By making the invisible visible and preserving the momentary, photography introduced a new “language of reality.” It demanded reinterpretations of memory, history, and identity.

Suddenly, images became evidence—used by scientists to document phenomena, by historians to record events, by families to preserve memories, and by journalists to witness truth.

This language transcended words, powers, and borders. The camera’s mechanical eye saw what could not be altered or apologized for; reality was given a new voice—one shaped by photons and chemistry instead of letters and brushstrokes.

Early Reception: Skepticism, Wonder, and the Seeds of Enthusiasm

When Niépce’s first exposure emerged, it was met with a mixture of awe and skepticism. The scientific community marveled at the process’s ingenuity but questioned its practical applications. Artists debated its aesthetic merits, while conservative circles viewed it as a threat to tradition.

Yet enthusiasm grew rapidly, fueled by publications, exhibitions, and social networks. Photography clubs sprouted, societies debated the technology’s potential, and inventors tinkered. Controls over exposure, plate preparation, and chemical solutions sparked vibrant dialogues.

In less than two decades, the novelty of the first exposure ripened into an accessible culture of image-making with profound social implications.

The Global Ripple Effects: How the First Exposure Transformed Other Nations

Though born in France, the impact of Niépce’s initial photograph spread swiftly across Europe and beyond. England, the United States, and Germany became centers for photographic innovation, adapting and diverging according to local scientific traditions and cultural tastes.

Colonial enterprises used photography for documentary and ethnographic purposes, often with complex and problematic implications, reflecting power dynamics. Across continents, photography altered archives, news, science, and even warfare.

In the global embrace of photographic technology, the first exposure sowed seeds of a worldwide visual culture, linking diverse peoples through shared images.

Bridging Science and Art: The Photograph’s Dual Identity

Photography has always inhabited a unique space between art and science. Niépce’s first exposure exemplified this tension: a chemical experiment producing an image that is both methodologically scientific and profoundly aesthetic.

This duality challenged Victorian-era thinkers and continues to spark debate. Was photography mere replication or creative interpretation? Was its objectivity a strength or a deception? These questions defined early photography’s role in museums, laboratories, and studios.

Niépce’s legacy reminds us that art and science are not opposites but complementary forces enriching human understanding.

From Experiment to Industry: The Economic Consequences of Early Photography

The success of early photographs ushered in new industries—from camera manufacturing to photo printing, from portrait studios to illustrated newspapers.

Entrepreneurs saw opportunity, while artists and technicians created new professions. The economic implications were vast, affecting everything from consumer culture to communication modes.

France benefited greatly, but the forces of industrialization meant rapid expansion worldwide. The first exposure initiated a market for images that would ultimately reshape advertising, journalism, and entertainment.

The Human Dimension: Stories of Those Who Witnessed the Birth of Photography

Beyond inventions and theories, the human stories surrounding the first exposure bring the history to life. Niépce’s family, his small rural community, early collaborators—all lived on the cusp of a technological earthquake.

Letters reveal wonder and frustration; diaries capture astonishment at visiting studios; early subjects describe their portraits with affection and curiosity. For many, the photograph was an emotional artifact, a new way to connect with memory and identity.

These personal narratives remind us that technology is deeply human—born from feeling, creativity, and hope.

Ethical and Philosophical Reflections: What Did It Mean to Capture Reality?

Photography’s capacity to “take” a moment unleashed profound ethical and philosophical dilemmas. Did a photograph represent the truth, or a manipulation? What of privacy, consent, or historical bias?

Niépce’s first exposure, though innocent in intent, opened questions about image ownership and authenticity that resonate today—from deep fakes to digital manipulation.

Photography challenged humankind to reconsider what it means to witness, remember, and narrate existence.

The Enduring Mystery: Technical Debates About the Exact Methods Used

Despite extensive research, historians and scientists still debate some aspects of Niépce’s exact chemical formula and exposure technique. The original plate’s fragility complicates analysis; Niépce’s own notes are incomplete or coded.

This mystery is part of the photograph’s allure—combining a precise scientific breakthrough with a human enigma. Over two centuries later, new imaging techniques continue to reveal its hidden textures, breathing life back into the shadows of Le Gras.

The first exposures remain a fertile ground for wonder, bridging past and present through unanswered questions.

The Preservation and Rediscovery of Niépce’s First Photograph

For many decades, Niépce’s pioneering image was lost to history, overshadowed by daguerreotypes and later processes. Its eventual rediscovery in the 20th century enriched photographic scholarship and deepened appreciation for early inventors.

Preservation efforts are ongoing, involving fragile plates, archives, and digital restorations that unlock details invisible to the naked eye.

This rescue operation from oblivion reflects the broader cultural commitment to honor and understand our visual heritage.

Photography First Exposure and the Modern World: Continuities and Inspirations

Today, nearly 200 years later, the influence of Niépce’s first exposure resonates in every camera click, every image shared. From smartphones to satellites, photography fuels modern communication, creativity, and surveillance.

Yet, at its core, photography remains a dialogue with light, time, and perception—a legacy birthed in France’s quiet countryside on that fateful day.

Recognizing this origin deepens our respect for the image as more than pixels on a screen, but as an enduring human impulse to see, preserve, and share reality.

Conclusion

The first photographic exposure in France—Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s View from the Window at Le Gras—marks one of humanity’s most extraordinary moments. It is where light became a storyteller, chemistry a scribe, and a fleeting moment found immortality through hard science and passionate curiosity.

This image was imperfect and obscure, but therein lay its power: to chart a new territory at the intersection of art, science, and memory. It opened a door to a visual revolution that has reshaped how we see ourselves, each other, and the world. The first exposure is not just a technical milestone; it is a profound human achievement—an enduring reminder that, to capture light is to capture life itself.

FAQs

1. What exactly was the photography first exposure of 1826?

It was the first successful permanent photograph, created by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in France, capturing a view from his window at Le Gras using a heliographic process.

2. Why did the exposure take so long to capture?

Because the light-sensitive materials available then were very slow to react, Niépce’s process required approximately eight hours of sunlight to produce a lasting image.

3. How did Niépce’s invention influence later photographic techniques?

Niépce’s heliography introduced the principle of light sensitivity, inspiring Louis Daguerre and others who developed faster, more practical photographic methods like the daguerreotype.

4. Was the first photograph immediately appreciated worldwide?

No; the image was initially met with skepticism and limited awareness. Its significance grew over decades as technology advanced and photography spread.

5. What were some challenges in preserving Niépce’s first photograph?

The original plate was fragile and susceptible to damage, and it was nearly lost for a long period. Preservation involved careful handling and modern restoration techniques.

6. How did photography change society after its invention?

Photography democratized visual representation, became a tool for documentation, art, journalism, and science, fundamentally altering perceptions of reality and memory.

7. Did Niépce consider himself an artist or a scientist?

He was both—a poet of light and a meticulous experimenter—bridging the gap between creative imagination and rational inquiry.

8. What philosophical questions did the advent of photography raise?

It challenged ideas about objective truth, memory, identity, privacy, and how images should be interpreted or trusted.