Table of Contents

- A Young Senator Steps Onto Rome’s Grand Stage

- From Ashes of Vesuvius to the Marble Halls of Power

- Education, Patronage, and the Making of a Roman Advocate

- The Office of Quaestor: Gateway to the Roman Ruling Class

- Rome in 91 CE: An Empire at Once Triumphant and Uneasy

- First Day in the Curia: Ceremony, Anxiety, and Ambition

- Money, Grain, and Letters: The Everyday Work of a Quaestor

- Serving the Emperor: Loyalty, Fear, and the Politics of Survival

- Voices in Marble Corridors: Oratory and Reputation in the Senate

- Friends, Rivals, and Patrons: The Social Web Around Young Pliny

- Behind Closed Doors: Moral Choices in an Autocratic Age

- From Quaestor to Consul: How 91 CE Shaped a Career

- Letters as Windows: Reconstructing Pliny’s Quaestorship

- Wider Ripples: What Pliny’s Office Meant for the Roman People

- The Shadow of Domitian: Memory, Terror, and Later Justifications

- Pliny the Younger in Historians’ Eyes: Bias, Brilliance, and Blind Spots

- From Rome to Us: Why a Quaestor in 91 Still Matters Today

- Conclusion

- FAQs

- External Resource

- Internal Link

Article Summary: In the year 91 CE, pliny the younger quaestor entered the arena of Roman high politics at a moment when the Empire appeared solid yet was riddled with fear and suspicion. This article follows his journey from provincial youth to rising senator, unpacking the duties, loyalties, and compromises that defined a quaestor’s life under Emperor Domitian. It recreates the daily routines of finance, grain supply, and official correspondence, while tracing how oratory, patronage, and carefully managed friendships shaped Pliny’s ascent. Along the way, it explores the moral tension between service to an autocratic regime and fidelity to Roman ideals of liberty and virtue. Through narrative scenes, analysis of his surviving letters, and comparisons with other senators, we see how the young Pliny fashioned both a political career and a literary legacy. The story of pliny the younger quaestor reveals the hidden machinery of the Roman state, where junior magistrates quietly kept the empire running. It also invites us to question how later memory—especially in Pliny’s own polished letters—reframed those anxious early years in the Senate.

A Young Senator Steps Onto Rome’s Grand Stage

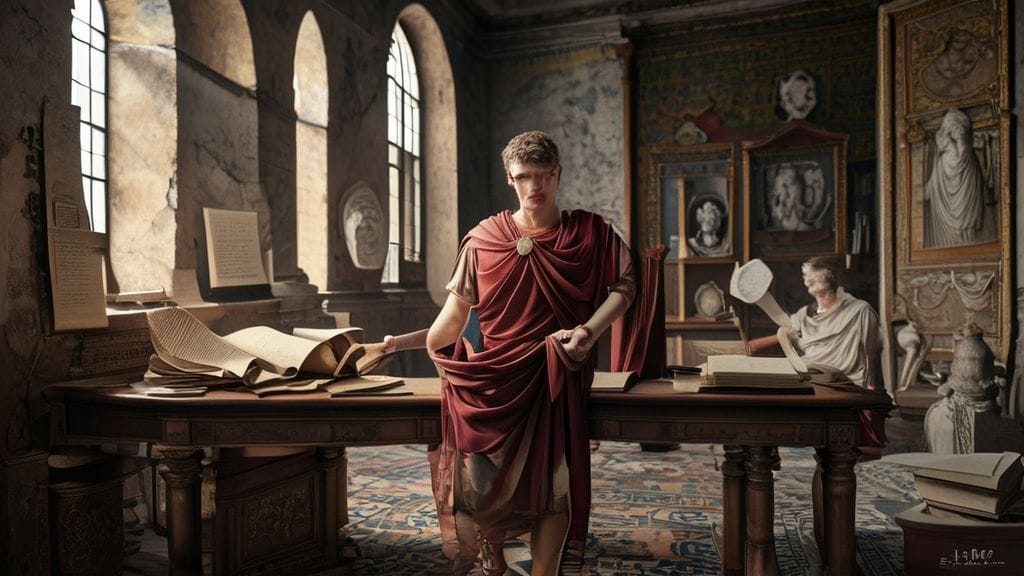

The year was 91 CE. In the heart of Rome, beneath the shadow of the Capitoline Hill, a thin, sharp-eyed man in his late twenties adjusted his toga with restless fingers. Before him loomed the Curia Julia, the Senate house, its bronze doors open like a mouth ready to swallow him. This was the day that pliny the younger quaestor would formally step into his first curial magistracy, the day that transformed him from a talented provincial advocate into a visible cog in the immense machinery of Roman power.

He was not the most famous man present—far from it. Aging consulars, battle-scarred generals, and priests of ancient cults filed past him with an air of practiced indifference. They had seen dozens of new quaestors come and go. For them, he was another name on the list, another young man to be tested, used, perhaps discarded. Yet for Pliny, every column, every whisper, every echo of sandals on the marble floor seemed magnified. The moment shimmered with possibility and danger.

To us, the word “quaestor” sounds technical, bureaucratic, even small. But in Rome’s intricate hierarchy, it was the gateway into the Senate itself—a rite of passage that would define the trajectory of a man’s life. For pliny the younger quaestor, nothing about this was small. It was the pivot between obscurity and remembrance, between the silent multitudes of citizens and the narrow, storied class that ruled them.

But this was only the beginning. Behind the stately rituals and the carved stone lies a more fragile story: of a man who had already witnessed catastrophe, who knew something of loss and fear, and who now had to learn how to survive in a court that smiled in public and condemned in private. To understand the weight of this first office, we must step back—to the shores of Campania, to a sky darkened by ash, and to a boy who watched an empire shaken by forces larger than any emperor.

From Ashes of Vesuvius to the Marble Halls of Power

Two decades before he donned the toga of a quaestor, Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus was simply a boy called “Secundus,” growing up amid the villas and vineyards along the Bay of Naples. His future seemed comfortable but not necessarily exceptional: the son of a well-connected equestrian family, orphaned early but adopted by his scholarly uncle, Pliny the Elder. That uncle’s house was his school, his refuge, and his window onto the wider world.

In 79 CE, when Pliny was about seventeen, the bay that framed his childhood turned into the stage of an apocalypse. Mount Vesuvius erupted, spewing fire and ash over Pompeii and Herculaneum. Pliny watched from Misenum as his uncle, commander of the fleet, sailed toward the catastrophe in a doomed attempt at rescue. Later, in his famous letters to Tacitus, he would reconstruct those hours with a historian’s attention and a nephew’s grief, describing “a cloud of unusual size and shape” that rose from the mountain like a pine tree.

The eruption was more than a natural disaster. It cracked open the illusion of Roman invincibility. An empire that claimed to govern the world could not stop its own earth from turning against it. For Pliny, the drama of that day—his uncle’s calm decision to risk his life, the chaos of fleeing crowds, the ash that rained like a toxic snow—etched into his mind the sense that life, however honored or powerful, could be cut short without warning.

When he later entered public life as pliny the younger quaestor, that memory would not have vanished. Beneath the marble floors of the Curia, beneath the rehearsed speeches and polished compliments, he carried the silent knowledge that fame and rank were brittle shields against fate. His uncle, a prolific scholar and naval commander, had perished on the beach; the mountain did not care about titles.

This experience helps us read his later career not merely as a ladder climbed but as a series of bets placed against uncertainty. If one cannot control volcanoes or emperors, perhaps one can control one’s own words—polishing letters and speeches that might endure after the speaker is dust. The path that brought him to quaestorship in 91 CE wound through rhetorical schools, law courts, the patronage of powerful men, and the expectations of a social order that demanded excellence and obedience in equal measure.

Education, Patronage, and the Making of a Roman Advocate

Before he could stand among senators, Pliny had to master the one art that opened doors in Rome: eloquence. The boy from Comum, brought into the orbit of Rome’s intellectual elite by his uncle, spent his formative years in the city’s rhetorical schools. In dim lecture halls, where wax tablets scratched and voices rose in practiced cadences, he learned to speak about everything and nothing: fictitious lawsuits, imagined tyrants, idealized heroes. These exercises were not games; they were drills in power.

Rome believed that the spoken word could move armies, sway juries, and topple reputations. Pliny’s teachers—men like Quintilian, whose Institutio Oratoria would later codify the art of rhetoric—pushed their students to combine memory, logic, and passion. A future senator had to know how to strike just the right note: bold without being reckless, flattering without seeming servile, indignant without overstepping the invisible boundaries of imperial tolerance.

Patronage was woven into every part of this education. As a youth, Pliny attached himself to influential figures, attending their morning levees, shadowing them in the Forum, applauding their speeches, and offering carefully phrased compliments. An approving glance, a small commission, a chance to speak in a lower court—these were the rungs of his ascent. When a patron recommended a young man for office, he was vouching not only for talent but for loyalty.

By the time pliny the younger quaestor presented his name for the cursus honorum, he was more than a promising lawyer. He was a known quantity: a man whose inheritance was confirmed, whose estates were in order, whose speeches had already stirred applause in the basilicas where judges sat. The city had watched him perform. Now the Empire would see what he could do with an official seal in his hand.

Yet behind the celebrations of office, one must imagine the quiet calculations. What did it mean to enter magistracy under Emperor Domitian, a ruler whose frown could end a career, whose whispers could end a life? To climb in such a world was to learn precisely where courage stopped and prudence began—and to pray that the line would not shift overnight.

The Office of Quaestor: Gateway to the Roman Ruling Class

To understand the significance of pliny the younger quaestor, we must first grasp what a quaestor actually was. In the early Republic, quaestors were primarily financial officers—men entrusted with the army’s pay chests, the state’s treasury, the arithmetic of conquest. By the time of the Empire, their role had diversified and, in some respects, diminished. Imperially appointed procurators handled much of the real financial muscle; emperors themselves, aided by freedmen and secretaries, steered large-scale revenues.

Yet the quaestorship remained symbolically crucial. It was the first formal step in the cursus honorum, the ladder of offices that led through praetorship to the consulate, the pinnacle of a senatorial career. To hold the quaestorship meant entry into the Senate and its laced-up, rule-bound fraternity. It meant a reserved seat in the theater, an official title, a place in Rome’s memory.

Quaestors could be assigned to various tasks. Some were attached to provincial governors, handling correspondence, finances, and logistics at the Empire’s edges. Others served in Rome itself, assisting the urban prefect or the city’s grain supply administration. Still others were “quaestors of the emperor,” involved in managing imperial finances, archives, or communications. Scholars debate the exact nature of Pliny’s post in 91 CE—whether he served in the city, in the imperial treasury, or in a more specialized capacity. His letters are tantalizingly vague, a silence that may itself be meaningful.

Whatever the exact posting, the reality was this: a quaestor had enough power to matter, but not enough to defy. He signed documents, supervised subordinates, and oversaw public money, all under the watchful eyes of superiors who expected efficiency and discretion. If a quaestor performed well, he gained allies; if he offended or blundered, his career could stall at its very outset.

It’s astonishing, isn’t it, how much of history depends on these junior officials whose names we often never learn? Pliny is an exception because he wrote. Through him, the quiet, clerical face of Roman power comes into view: not only battles and decrees but ledgers, schedules, and the daily choreography of governance that kept the vast Empire from collapsing under its own weight.

Rome in 91 CE: An Empire at Once Triumphant and Uneasy

When pliny the younger quaestor took up his office, Rome outwardly glittered with triumph. Domitian had completed the Colosseum, adorned the city with statues and grand building projects, and presented himself as the stern but beneficent guardian of Roman order. The legions guarded the Rhine and Danube frontiers; the East was broadly quiet; the grain fleets still arrived from Africa and Egypt. To a casual observer, the Empire of 91 CE looked secure.

Yet behind the celebrations, a colder reality pulsed. Domitian had grown increasingly suspicious of the senatorial class. Accusations of treason, often vague and opportunistic, circulated in hushed tones. Informers—the hated delatores—prowled the city, ready to twist a careless joke or an ambiguous phrase into a charge of disloyalty. Trials for maiestas (treason) could lead to confiscation of property, exile, or forced suicide. The Senate, once the proud council of Rome’s masters, had learned to applaud when the emperor entered and fall silent when he frowned.

This climate shaped the world that greeted young Pliny. His first steps as a magistrate were taken on ground that felt firm but was riddled with cracks. Any official act, any speech in the Curia, any friendship he cultivated might one day be reinterpreted in a darker light. Historians like Tacitus, writing later under safer emperors, would paint Domitian’s reign as a time of “slavery,” when “we lost even the capacity for indignation.” Yet those words, though powerful, cannot fully capture the uncertain calculations of those who still had to live and work under that regime.

For a quaestor, the challenge was to be visible but not conspicuous, useful but not threatening. Domitian valued competence, and he rewarded loyal service with promotions and honors. Pliny, an efficient administrator and gifted orator, could hope to benefit—but only if he managed to appear deferential, measured, and impeccably orthodox in his public loyalty. One misjudged phrase in the Senate, one poorly handled financial case, might feed the emperor’s suspicions.

Walking into this atmosphere on that first official morning, Pliny would have felt the weight not just of tradition but of surveillance. Rome in 91 was a city where statues commemorated peace while whispers foretold danger. A young quaestor had to learn quickly how to read the room—and when to say less than he knew.

First Day in the Curia: Ceremony, Anxiety, and Ambition

Imagine the first day dawn: the sky over Rome lightening into a dusty gold, the streets slowly filling with clients, slaves, and senators’ litters. Pliny, rising perhaps before sunrise, would have been assisted by slaves in the elaborate process of dressing: tunic, then toga, that heavy swath of wool that required practice to wear with elegance. His household—freedmen, servants, perhaps relatives—would have watched with a mixture of pride and apprehension. Their fortunes, too, were tied to his steady ascent.

As he approached the Forum, the city’s voices gathered into a murmur. Vendors called out prices; litigants hurried toward the basilicas; petitioners awaited a chance glimpse of some patron. The Curia’s steps were scrubbed clean, its bronze doors burnished, the gilded ceiling inside glowing softly in the morning light. Within, clerks arranged wax tablets and scrolls; lictors inched into position, their bundled rods—a memory of republican severity—resting against muscled shoulders.

When pliny the younger quaestor crossed the threshold, he was enacting a script centuries old. New senators and magistrates had been entering that space since Julius Caesar rebuilt the Curia. Yet for each man, the ritual felt singular. He might have exchanged a nod with an older senator he knew from the courts, bowed respectfully to ex-consuls whose careers he envied, or offered a quick word of greeting to a fellow novice with whom he’d shared the grueling training of rhetorical schools.

The proceedings of such a day were formal: roll calls, oaths, announcements of assignments, possibly speeches marking the assumption of office. But beneath the protocol pulsed a river of unspoken emotions. Pliny’s pulse likely quickened when his name was read, when he stepped forward to swear loyalty to emperor and state, when he felt dozens of seasoned eyes rest upon him. A single misstep—stumbling in his toga, mispronouncing a formula, appearing hesitant—could become fodder for quiet mockery.

And yet, he was not without confidence. Years of advocacy had trained him to stand before hostile audiences. His uncle’s memory, his education, his growing reputation as a stylist—all these were invisible armor. As he took his oath, he may have silently promised himself that this was only the beginning, that one day he would speak here as consul, not as a minor magistrate. Ambition, in Rome, was not a vice but a duty, provided it bowed first to the emperor’s will.

Money, Grain, and Letters: The Everyday Work of a Quaestor

Once the ceremonies faded, the reality of office began. Pliny’s days as quaestor were less about grand speeches and more about tasks that, though prosaic, were vital to the Empire’s functioning. In an age before modern bureaucracy, the Roman state still required an army of literate, numerate men to keep its promises: soldiers had to be paid, temples maintained, city projects funded, grain weighed and distributed, and a thousand petitions answered.

As pliny the younger quaestor, he may have risen early to review account tablets prepared by subordinate clerks—tallies of expenditures, revenues, and allocations. Rows of numerals, carefully inscribed in wax, represented more than ink or stylus marks; they were veteran stipends, contractor payments, subsidies to allied cities, or repairs to aqueducts. A careless error could spark rumors of embezzlement, invite an audit, or incur the wrath of superiors.

Some days would have been devoured by correspondence. Messengers arrived bearing reports from provincial governors, petitions from cities, complaints from private citizens. Letters had to be read, summarized, and answered in neat, clear Latin, sometimes in Pliny’s own hand but more often dictated to experienced secretaries. We know from his later letters how much pride he took in careful composition; one can easily imagine him, even as a quaestor, rephrasing a sentence to keep a tone respectful but firm, to grant a request without setting a dangerous precedent, or to deny a petition without making an unnecessary enemy.

If his assignment touched on the grain supply—a lifeline of the capital—he would have had to coordinate with administrators at the river port, warehouses, and distribution points. The people of Rome feared famine more than war; a disruption in the grain dole could trigger unrest, and an unrestful capital was every emperor’s nightmare. Behind the ritual language of edicts, real stomachs grumbled, real crowds swelled. Pliny’s signature on a tablet, ordering grain from one warehouse to another, might mean the difference between calm and anger in a crowded forum.

Then there were the audiences: minor officials, contractors, petitioners, and sometimes those with enough influence to demand a hearing. The quaestor’s office was a threshold space, where ordinary lives brushed against imperial structures. A veteran seeking overdue pay, a landlord contesting a tax, a provincial envoy pleading for funds to rebuild a burned temple—such people arrived with stories that never made it into marble inscriptions but formed the daily soundtrack of governance.

In all this, Pliny was learning not only administration but the art of balance: between generosity and frugality, firmness and flexibility, law and expediency. These were the skills that would later serve him as governor of Bithynia; but they were first tested here, in the modest yet consequential routines of his quaestorship.

Serving the Emperor: Loyalty, Fear, and the Politics of Survival

No matter how routine his days might appear, Pliny worked in the long shadow of Domitian. Officially, loyalty to the emperor was an unquestioned virtue. Public inscriptions hailed him as “Lord and God” (dominus et deus), and the Senate, cowed by years of purges and accusations, had learned to echo the language of adulation. A young magistrate like pliny the younger quaestor was expected to reflect that loyalty not only in ritual but in his everyday decisions.

Consider a simple case: a dispute over funds in a provincial city where the local elite were divided into factions. One faction might align itself more closely with imperial policy, the other less so. How Pliny handled the allocation of subsidies or the endorsement of a municipal decree could signal, however subtly, his sense of what would please the emperor. To disregard such calculations would be naïve; to appear nakedly opportunistic would be dangerous. The dance required finesse.

At the same time, rumors about Domitian’s growing paranoia circulated in private. Some senators had been executed or exiled under murky charges; others had lost property. Pliny, later in life, would present himself as a man who maintained his dignity under tyranny without becoming a hero or a collaborator. In one of his letters, he contrasts “honest senators, who kept their thoughts free even while their words were fettered,” with flatterers who rushed to outdo one another in servility. It is tempting to read his own early career through that lens, to imagine him as quietly resistant, but the truth is more complicated.

Every letter he wrote, every financial decision he approved, every public speech he delivered as quaestor had to thread the needle between honest administration and political self-preservation. If he had condemned the emperor outright, his career—and likely his life—would have ended; if he had fawned too obviously, he would later have had difficulty presenting himself as a man of principle in the safer climate of Trajan’s reign. Survival itself became a moral act, constantly renegotiated.

In this respect, Pliny was not unique but representative. The entire senatorial order lived with this double vision: outward conformity, inward judgment. His particular distinction lies in the fact that he later wrote about it, offering us tantalizing but crafted glimpses into how a Roman aristocrat retrospectively framed his youthful choices under a regime that was, by then, safely condemned.

Voices in Marble Corridors: Oratory and Reputation in the Senate

Although paperwork consumed much of his time, Pliny did not enter the quaestorship merely to shuffle tablets. For a man trained in rhetoric, public speaking remained the surest path to visibility and influence. The Senate was his theater, its marble benches his audience, its attendant scribes his chroniclers. Even as a junior magistrate, he had chances—carefully circumscribed but real—to speak.

He might rise to support a motion regarding public works, to offer an opinion on a financial matter, or to praise a deceased senator. Each intervention was an audition. Older statesmen watched to see whether the young man spoke clearly, argued logically, and observed the unwritten rules of deference. Did he know when to yield? Did he avoid dangerous topics? Did his compliments to the emperor ring with sincerity—or too much enthusiasm?

Pliny later took pride in several high-profile cases he argued in the Senate and in the courts, though most belong to his post-quaestorian years. Still, the foundations of that fame were laid during this period. His style—as we know from his surviving letters—was polished, intricate, and sometimes self-conscious, but contemporaries also found it moving. He writes about once being called back for an encore reading of a speech, a sign that his performance had truly impressed his peers.

At least one anecdote, preserved in his correspondence, shows how delicate the balance could be. Recounting his own experiences as an advocate, he notes how he sometimes chose to speak briefly, “so as not to give offense by overshadowing my elders,” while at other times he dared a fuller display when the situation demanded it. One can easily imagine the young quaestor weighing such considerations before rising from his bench: this is not the day to shine too brightly; that senator will resent me; that topic is too fraught.

Through these calculated performances, his reputation slowly took shape. A good speech could echo through Rome faster than any official decree. In baths, dinner parties, and porticoes, people would murmur, “Have you heard the young Pliny speak?” For a class that lived by honor and rumor, such whispers were worth more than gold.

Friends, Rivals, and Patrons: The Social Web Around Young Pliny

Politics in Rome did not happen in isolation; it flowed through a dense web of friendships, rivalries, and reciprocal obligations. Pliny, far from being a solitary moralist, was deeply enmeshed in this network. As pliny the younger quaestor, he spent as much time cultivating relationships as he did reviewing accounts.

Morning salutations—the daily ritual in which clients and lower-status friends visited a superior’s home—were crucial. Pliny appeared both as a client, visiting older patrons, and as a minor patron in his own right, receiving those who sought his ear. At banquets, he listened more than he spoke, noting who aligned with whom, who laughed too loudly at dangerous jokes, who fell silent at the mention of certain names. A misplaced word over wine might reverberate in the Curia days later.

He also formed genuine friendships. His later letters reveal warm attachments to figures like Tacitus and Suetonius, and he likely forged their earliest bonds in this period. They shared not only political concerns but literary ones—criticizing each other’s drafts, trading allusions, and reading new works of history or poetry. In such circles, the boundaries between personal affection and political alliance blurred.

Rivals, too, emerged. Some men envied his eloquence, others his rising favor with certain patrons. A sharp remark in the Senate, a clever turn of phrase that won the house’s laughter at another’s expense, could cement a lasting enmity. In a system where later elections depended on peer support, such animosities mattered. Pliny had to learn when to wield his wit and when to sheath it.

These relationships were tested whenever the emperor moved against a member of their circle. If a senator fell under suspicion, did you visit his house? Did you defend him in the Senate? Did you remain conspicuously absent? Each choice signaled something about your character—and your sense of self-preservation. In one of his letters, Pliny later praised a friend who continued to show kindness to those in disgrace, even at personal risk. The compliment, veiled as it is, suggests the moral tightrope he and his peers walked in these years.

Behind Closed Doors: Moral Choices in an Autocratic Age

For all the public rituals of office, some of the most significant moments of Pliny’s quaestorship played out in private. Late at night, candles guttering in his study, he might review a difficult case or draft a speech that would tread close to sensitive ground. A slave quietly holding a lamp, scribes waiting with stylus and wax—this was the intimate workshop where he tried to reconcile conscience and career.

Imagine a scenario: a provincial city petitions for relief from crushing tax arrears, claiming poor harvests and local corruption. The law might allow for limited concessions, but Domitian’s administration, keen on revenue, prefers a harder line. Pliny must draft a report. Does he highlight the city’s suffering, risking the appearance of softness? Or does he emphasize the need to maintain standards, aligning himself with imperial priorities but perhaps condemning thousands to further hardship?

Such decisions rarely appear in inscriptions or formal histories; yet they constituted the moral core of administration. In a later letter, Pliny describes his own ideal official as a man who balances rigor with humanity, who is “neither harsh nor lax, but in all things guided by reason.” The formula sounds neat on paper. In practice, the pressures of hierarchy, expectation, and fear could twist “reason” into something more self-serving.

We know that Pliny took pride in his integrity. Writing under the more benign rule of Trajan, he portrayed himself as one who had managed to stay clean in a dirty time. Modern historians, however, urge caution. As Miriam Griffin once noted in a study of Roman aristocrats under the emperors, self-portraiture in such texts is “a negotiation with memory as much as with truth.” Pliny wanted his readers—especially younger men embarking on their own careers—to see him as a model of measured virtue.

Yet even if his later self-presentation is polished, the dilemmas he hints at ring true. To serve under Domitian was to navigate not clear moral lines but shifting grays. The young quaestor, poring over drafts in the half-light, must often have wondered whether he would one day have to account—to others or to himself—for the choices he was making now.

From Quaestor to Consul: How 91 CE Shaped a Career

The year 91 was not an isolated chapter but the opening volume of Pliny’s political life. The skills, alliances, and reputations he forged as quaestor would echo through his later offices. After the quaestorship came more posts: tribune of the plebs, praetor, and eventually, under the emperors Nerva and Trajan, the prestigious suffect consulate. By then, pliny the younger quaestor had long since become Pliny the Younger, consul and governor, a man whose name could command attention in the Senate and whose letters reached the emperor’s desk.

How did that first step influence all that followed? For one thing, it proved that he could handle responsibility under pressure. Efficient management of finances or correspondence, coupled with competent senatorial performances, marked him as reliable. Older senators and imperial advisors took note. One does not entrust a province to a man who bungled his earliest post.

Secondly, it situated him within specific political and familial networks. The same men he assisted or impressed as quaestor might later advocate for his candidacy in higher elections. The contracting firms, city councils, and provincial communities that benefited from his decisions would remember him when he later requested support or information. Rome’s power was personal, and the quaestorship gave Pliny his first chance to weave his own web.

Finally, it gave him raw material for the literary persona he would one day craft. The statesman who wrote to Tacitus, describing his uncle’s death at Vesuvius, or who corresponded with Emperor Trajan about Christians in Bithynia, was also the former pliny the younger quaestor who had learned early on how words could stabilize an Empire—or unsettle it. His habit of writing carefully observed letters about public life must have roots in these formative years, when every small decision seemed to tremble with larger implications.

Looking back from the vantage point of his later success, Pliny could trace a clear narrative: from promising youth to honored elder, each office a step on a rational, almost inevitable path. Reality, as always, was messier. The quaestorship was both an achievement and a gamble. A misstep, a shift in imperial favor, a single political storm could have stranded him there, another minor magistrate lost to history.

Letters as Windows: Reconstructing Pliny’s Quaestorship

One of the reasons we can speak so vividly about pliny the younger quaestor is that Pliny himself left us a rich collection of letters. Carefully edited and published in his lifetime, the Epistulae are a unique blend of personal reflection, anecdote, and self-fashioning. They include descriptions of his uncle’s death at Vesuvius, his life on his estates, his legal cases, his governorship in Bithynia, and his friendships with leading intellectuals of the age.

Yet when it comes to the specifics of his quaestorship, the letters are frustratingly sparing. He mentions the office, notes it in his cursus honorum, but rarely details particular cases from that year. Historians must, therefore, read between the lines. The bureaucratic expertise he later displays—his familiarity with provincial finances in Bithynia, for instance—strongly suggests hands-on experience in earlier posts. The administrative calm with which he discusses complex local disputes in his letters to Trajan did not spring from nowhere; it was forged in places like Rome’s treasury offices and senatorial committees.

In one of his letters (Book 1, Letter 5), Pliny describes advising a friend on whether to pursue a senatorial career, weighing the honor and danger. His tone carries the weariness of someone who has seen the inside of the machine, not merely its shining exterior. In another, he reflects on the satisfaction of overseeing public works done well and the embarrassment of those that fall short. These glimpses, though tied to later events, echo backward into his quaestorian year, giving us a sense of the attitudes he must have formed then.

Modern scholars, from Ronald Syme to more recent historians of Roman administration, use such evidence cautiously. They triangulate Pliny’s general comments on officeholding with other sources, such as inscriptions, laws, and the writings of contemporaries like Tacitus and Suetonius. A fragmented inscription might confirm the duties of a particular kind of quaestor; a passing remark in Suetonius might illuminate Domitian’s treatment of lower magistrates. Piece by piece, the mosaic fills in around the clearer portrait Pliny paints of himself.

In this way, the letters serve as both window and mirror. They let us peer into Pliny’s world but also reflect his desire to appear in a certain light: dignified, humane, competent, and, above all, worthy of remembrance. When he mentions his early offices, we can sense the older man nodding approvingly at his younger self, editing the past into a tidy prologue to later glory.

Wider Ripples: What Pliny’s Office Meant for the Roman People

It might be tempting to see the story of pliny the younger quaestor as purely aristocratic drama—a tale of careers and reputations trading places in marbled halls. But the consequences of his actions, and of others like him, radiated far beyond the Senate. The decisions made in his office touched lives in far-flung provinces, in crowded tenements, and in quiet country villas.

Consider the veteran waiting in a provincial town for news that his promised pension had been approved, or the citizen in Rome queuing for grain at a distribution point, or the city council in North Africa petitioning for help to repair a crumbling harbor. Their fates were bound, in part, to whether a quaestor had organized finances efficiently, whether correspondence was answered promptly, whether the bureaucratic arteries of empire were clogged or clear.

When a quaestor delayed a payment or misjudged a tax remission, the effects could be immediate: a shortage of coin in a border garrison, a municipal treasury pushed into insolvency, a merchant forced into ruin. When, by contrast, he acted swiftly and fairly, minor crises might be averted before they ever reached Rome’s ears. The empire’s apparent stability rested on these countless small acts of competence—or incompetence.

Pliny’s later writings reveal that he understood this interconnectedness. As governor of Bithynia, he worried about the finances of small towns, the cost of public baths, the mismanagement of building funds. That sensitivity, one suspects, was born in his early exposure to the dry but consequential world of accounts and petitions. Even if he did not fully grasp, at twenty-eight or twenty-nine, how his quaestorian decisions reverberated, he was surely aware that he was handling more than mere numbers.

Thus, the story of his quaestorship is not only about one man’s ascent but about the invisible infrastructure of imperial rule. Rome’s power did not simply flow from legions and emperors; it depended on men like Pliny, sitting in modest offices, translating the vast, abstract idea of empire into daily, concrete choices that made life bearable—or unbearable—for millions.

The Shadow of Domitian: Memory, Terror, and Later Justifications

Domitian’s reign ended in 96 CE with his assassination in a palace conspiracy. The Senate, which had so long applauded him, suddenly found its voice. He was condemned in a formal damnatio memoriae; his name was erased from inscriptions, his statues pulled down. Under the new emperor Nerva and, more decisively, under Trajan, the political climate shifted. Men who had survived Domitian’s suspicions now had to recast their pasts in a moral key that fit the new age.

It was in this context that Pliny published his letters and delivered the Panegyricus, an elaborate speech of praise for Trajan that sharply contrasts the new emperor’s virtues with Domitian’s vices. In that speech and in the letters, pliny the younger quaestor of 91 becomes part of a larger narrative: the story of honorable senators enduring a time of “slavery” who now rejoice in “liberty” restored. He emphasizes restraint, dignity, and the quiet preservation of inner freedom amid outward conformity.

One cited passage—often noted by historians—has Pliny recalling how under Domitian “we did not dare even to think freely.” The hyperbole is deliberate; it casts the previous regime in the darkest possible light, thereby making Trajan’s sunshine all the brighter. But it also serves another function: it justifies the compromises Pliny and his peers made. If the age was one of terror, then survival, even with concessions, can be framed as a kind of courage.

Modern scholars are divided on how harshly to judge such self-fashioning. Some see in Pliny a typical aristocrat adept at shifting with the political winds. Others credit him with genuine moral reflection and a sincere desire to live up to the ideals he articulates. The truth, as usual, is somewhere in between. What is certain is that his memory of his quaestorship, like his memory of everything under Domitian, was filtered through the need to make sense of a dangerous youth from the safety of a more benign old age.

This tension makes Pliny a compelling, if sometimes elusive, witness. He reveals much, but always at a calculated angle. His portrayal of himself as a young magistrate under tyranny has shaped how generations have imagined the senatorial experience under Domitian. Yet behind his polished sentences, we can still sometimes glimpse the uncertain, ambitious, anxious young man he once was.

Pliny the Younger in Historians’ Eyes: Bias, Brilliance, and Blind Spots

Because of his letters, Pliny has long enjoyed a privileged place in the study of the early Empire. He appears in textbooks as a model of Roman gentlemanliness, his words quoted in translation: his description of Vesuvius, his accounts of villas and country life, his correspondence with Trajan about Christians. Yet when we zoom in on the figure of pliny the younger quaestor, historians have to grapple with the limits and biases of his testimony.

On the one hand, his insider’s perspective is invaluable. Few other sources offer such intimate glimpses of senatorial life under Domitian, Nerva, and Trajan. His careful Latin, his eye for detail, and his willingness to discuss administrative minutiae give us unique access to the mechanics of Roman governance. It is largely thanks to Pliny that we can imagine what it felt like to balance rhetoric, law, and imperial expectation in the corridors of power.

On the other hand, his social position and personal aims narrow his vision. As a wealthy senator, he largely ignores the experiences of slaves, the urban poor, and non-elite provincials, except when they intersect with his interests. His perspective on Domitian is colored by the need to flatter Trajan; his depictions of his own conduct are shaded by the desire to appear consistently virtuous. As the historian Fergus Millar once noted about such aristocratic sources, “we see Rome from above, and never from below.”

Yet even these blind spots are instructive. They remind us that history, especially when written from within the ruling class, is always a negotiation between memory, image, and fact. Pliny’s silence about certain aspects of his quaestorship—particular cases, specific confrontations—may indicate not that nothing happened, but that some things were best forgotten, or at least left unmentioned in a public collection of letters.

Still, despite these limitations, Pliny’s voice has endured because it captures something universal: the anxiety of serving a powerful system, the desire to be both successful and good, the need to make sense of one’s youth from the vantage point of later years. In the end, we read him not just for data about quaestorial duties but for the human drama that underlies every entry in a Roman fasti of magistrates.

From Rome to Us: Why a Quaestor in 91 Still Matters Today

At first glance, the story of pliny the younger quaestor in 91 CE might seem remote. The marble Curia has long since fallen silent; the Empire whose finances he helped manage is a chapter in textbooks; the volcano that shaped his youth now erupts only sporadically. And yet, his experience resonates with questions that still haunt modern societies.

What does it mean to serve a state that does good and harm in uneven measure? How does a conscientious official navigate systems that reward loyalty more than honesty, stability more than justice? When does accommodation become complicity? Pliny’s careful balancing act under Domitian—loyal but not obsequious, cautious but not paralyzed—mirrors dilemmas faced by civil servants, judges, and administrators in many times and places.

His faith in the power of writing also speaks across the centuries. By preserving his letters, he sought to shape how posterity would judge him and his age. We, too, live in a world where records—official and personal—will survive in ways we can scarcely imagine. The young people who enter public service today may one day look back, like Pliny, and try to arrange their memories into a narrative that justifies their choices.

Finally, his story reminds us that history is often made not only by emperors and generals but by the quieter hands that sign documents, balance accounts, and interpret laws. The empire of Domitian did not endure because of statues or slogans; it endured, for a time, because men like Pliny showed up every day, read their tablets, made decisions, and kept the wheels turning. When those wheels finally slowed and the Empire crumbled centuries later, it was, in part, because the class of administrators and magistrates that once sustained it had changed, faltered, or disappeared.

To trace the year 91 CE through Pliny’s eyes is to see how much rests on the shoulders of the almost-anonymous: the junior officials, the early-career bureaucrats, the aspiring orators. It is to realize that today’s “quaestors”—whatever their modern titles—stand in a long lineage of people whose seemingly modest work quietly shapes the fate of states and societies.

Conclusion

The figure who entered the Curia in 91 CE as pliny the younger quaestor was at once typical and singular. Typical, because he followed a familiar path of education, patronage, and office through which Rome’s senatorial class replenished itself. Singular, because he would later become one of the few such men to leave behind a literary record so vivid that we can still almost hear his voice. Through his experience, we have followed the thread of a young aristocrat’s life as it wound through danger, opportunity, and moral ambiguity in the age of Domitian.

We have watched him learn the craft of administration: balancing accounts, answering petitions, and managing the unglamorous but essential tasks that sustained an empire. We have seen him navigate a political landscape where praise for the emperor was compulsory, yet overzealous flattery could prove as risky as quiet dissent. We have glimpsed the private moments—real or imagined—when he pondered the gap between his ideals and the compromises his career demanded.

In the end, Pliny’s quaestorship was not the most dramatic year of Roman history, but it was a crucible for a man whose later actions and writings would help define our image of his age. The story of that year illuminates both the fragility of individual conscience under autocracy and the durable importance of seemingly minor offices in the functioning of great states. His letters, though shaped by hindsight and self-presentation, grant us a rare intimacy with the inner life of a Roman magistrate, neither hero nor villain, but something more complex and recognizably human.

To study pliny the younger quaestor is to be reminded that history’s grandeur often rests on mundane routines, that moral choices are frequently made in ledger columns and draft replies, and that the past lives on most powerfully when those who inhabited it found the courage—and the vanity—to write. Across nearly two millennia, that young man in his heavy toga still walks into the Curia, his heart racing, his future unwritten, carrying with him both the weight of Rome and the fragile hope of his own remembrance.

FAQs

- Who was Pliny the Younger when he became quaestor in 91 CE?

Pliny the Younger was a well-educated member of the Roman senatorial class, originally from Comum in northern Italy and adopted by his learned uncle, Pliny the Elder. By 91 CE he had already gained a reputation as a skilled advocate and literary man in Rome. His appointment as quaestor marked his formal entry into the senatorial magistracies and the beginning of his official political career. - What exactly did a quaestor do in the Roman Empire?

A quaestor was a junior magistrate responsible primarily for financial and administrative tasks. These included managing public funds, overseeing payments and receipts, handling parts of the grain supply or treasury, and conducting official correspondence. The role varied depending on the specific assignment—some quaestors served in Rome itself, others with provincial governors—but in every case it was the first recognized step on the cursus honorum, the traditional ladder of offices. - How did serving as quaestor influence Pliny’s later career?

Pliny’s quaestorship gave him practical experience in administration, exposed him to the workings of the Senate, and helped him build crucial relationships with powerful patrons and colleagues. His efficiency and discretion in this early role likely contributed to his later promotions, including the praetorship, the consulship, and his governorship of Bithynia. The skills he displayed—especially in finance and correspondence—are clearly reflected in his later letters to Emperor Trajan about provincial governance. - What was the political climate in Rome when Pliny was quaestor?

In 91 CE, Rome was ruled by Emperor Domitian, whose regime combined outward prosperity with increasing suspicion of the senatorial class. Accusations of treason, the presence of informers, and occasional purges created a climate of fear and caution. Senators and magistrates like Pliny had to navigate this environment carefully, publicly expressing loyalty to the emperor while privately worrying about sudden changes in fortune. - Do Pliny’s letters describe his quaestorship in detail?

Pliny’s surviving letters occasionally mention his quaestorship but do not give a detailed account of his day-to-day duties in that year. Historians reconstruct his early administrative experience by reading his later comments on officeholding and administration in conjunction with other sources, such as inscriptions and legal texts. Still, his letters provide invaluable context about the expectations, pressures, and moral dilemmas faced by Roman magistrates of his rank. - Why is Pliny the Younger important as a historical source?

Pliny the Younger is crucial because his letters offer a rare, first-person perspective on Roman political, social, and cultural life in the late first and early second centuries CE. He comments on everything from natural disasters and legal trials to villa architecture and literary debates. His position as a senator and magistrate allows historians to see the inner workings of Roman administration from the viewpoint of an educated insider. - How did Pliny later portray his service under Emperor Domitian?

Writing under the safer regimes of Nerva and Trajan, Pliny depicted Domitian’s reign as a time of repression and fear. He presented himself and like-minded senators as men who preserved inner integrity while outwardly conforming to necessity. In his Panegyricus in honor of Trajan, he contrasted the new emperor’s virtues with Domitian’s vices, thereby recasting his own earlier service as honorable endurance under an oppressive ruler. - What can Pliny’s quaestorship teach us about everyday governance in the Roman Empire?

Pliny’s early office illustrates how much of the Empire’s stability depended on mid-level administrators and magistrates handling finances, petitions, and logistics. Although emperors and generals dominate the headlines of ancient history, it was officials like Pliny who ensured soldiers were paid, cities received funds, and grain reached the capital. His career underscores the central role of capable bureaucracy in maintaining a vast imperial system. - Did Pliny face moral dilemmas as a young magistrate?

Although he does not give case-by-case confessions, Pliny’s later reflections strongly suggest that he and his peers faced real moral dilemmas under Domitian. They had to decide how far to go in satisfying imperial expectations, when to speak up in defense of others, and when to remain silent. His letters hint at the tension between ideal Roman virtues—justice, moderation, courage—and the practical need to safeguard one’s family, property, and future. - Why should modern readers care about Pliny’s year as quaestor?

Pliny’s quaestorship offers a window into how individuals navigate power structures that are larger than themselves—a theme that remains deeply relevant. His struggles to balance ambition and integrity, to serve a state that could be both beneficial and oppressive, and to shape his legacy through writing echo in the dilemmas faced by officials and professionals today. Studying his early office helps us understand not only the Roman Empire, but also the enduring human challenges of public service.

External Resource

Internal Link

Other Resources

- Encyclopaedia Britannica – general search for the exact subject

- Google Scholar – academic search for the exact subject

- Internet Archive – digital library search for the exact subject