Table of Contents

- The Dawn of a New Republic: March 2, 1836, Washington-on-the-Brazos

- Setting the Stage: Texas Under Mexican Rule

- Rising Tensions: Anglo Settlers and Tejanos Unite

- The Spark of Rebellion: From Dissent to Declaration

- Gathered at Washington-on-the-Brazos: The Convention Begins

- Portraits of the Founding Fathers: Visionaries of Texas Independence

- Drafting the Declaration: Language of Freedom and Resolve

- The Political Landscape: Republic or Annexation?

- The Immediate Aftermath: Responses from Mexico and the United States

- The Lone Star Emblem: Symbols of a New Nation

- Blood and Sacrifice: The Alamo and Goliad as Backdrops

- Samuel Houston’s Rising Command: Military and Moral Leadership

- International Recognition: Challenges for a Nascent Republic

- The Struggle for Governance: Early Republic Institutions and Policies

- Economic Dreams and Realities: Land, Trade, and Expansion

- The Role of Slavery: Controversies Within the Republic’s Foundations

- Cultural Hybridization: Anglo and Tejano Identities Intertwined

- The Republic’s Short but Turbulent Existence (1836-1845)

- Annexation by the United States: Texas’ Complex Path

- Legacy and Memory: How Texas Remembers March 2, 1836

- Lessons from the Republic: Independence, Identity, and Power

- Conclusion: The Resonance of a Republic Declared

- FAQs: Understanding the Republic of Texas

- External Resource

- Internal Link

1. The Dawn of a New Republic: March 2, 1836, Washington-on-the-Brazos

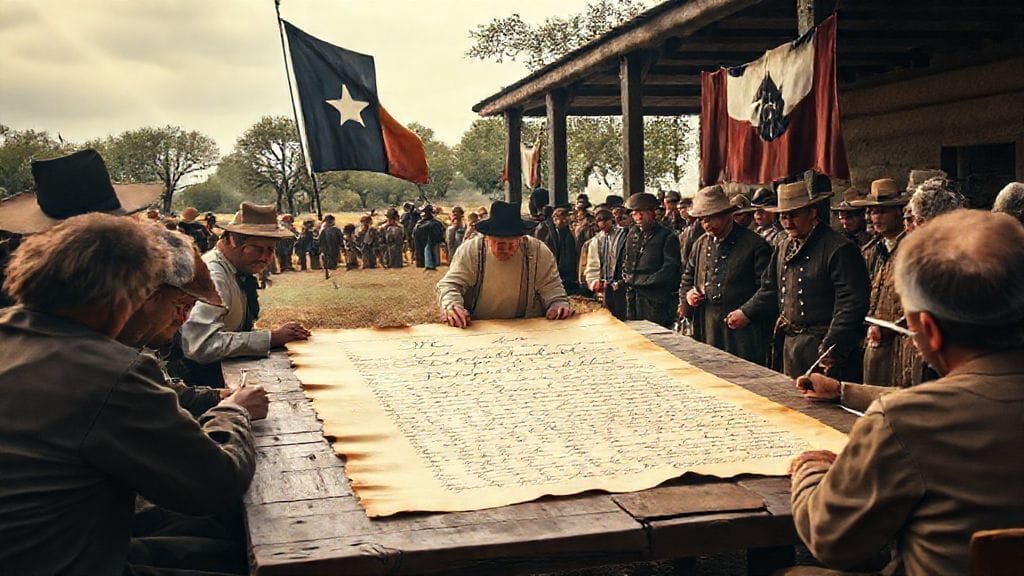

Morning mist still clung to the Brazos River when delegates convened under the hot Texas sun. Inside a modest wooden building, known simply as the “Old Three Hundred” gathering place, voices rose with a mixture of resolve and trembling hope. It was March 2, 1836, a date etched forever into the tapestry of Texan—and American—history. Here, amid the whispers of cotton fields and the echoes of horseback boots on dusty paths, the Republic of Texas was declared. A bold, audacious birth amidst uncertainty and turmoil.

This was not merely a political act; it was a declaration steeped in courage—a pledge to self-determination echoing the revolutions of the past but born in the raw, untamed lands of the American Southwest. The men present—Anglo settlers, Tejanos, and visionaries—acted not just as founders of a new political entity but as torchbearers of a promise: freedom from Mexican rule, a new destiny carved by the will of the people.

2. Setting the Stage: Texas Under Mexican Rule

To understand the weight of this moment, one must step back a decade or two. Texas, then part of Mexico, was a sprawling frontier, a land of promise and peril. The region had once belonged to Spain, then transferred to Mexican control after independence in 1821. Mexican authorities, eager to populate and stabilize the region, had invited Anglo-American settlers, granting land contracts and some measure of autonomy. Stephen F. Austin was the most prominent empresario whose colony drew hundreds of settlers.

But the relationship between these settlers and the Mexican government grew strained. Mexico’s attempts to enforce national laws—especially those concerning customs, taxes, and slavery—stoked a simmering resentment. Political upheavals in Mexico City, where centralists clashed with federalists, only added to the chaos. Texans, largely Anglo and Protestant, found themselves disenfranchised under increasingly authoritarian Mexican presidents like Antonio López de Santa Anna.

3. Rising Tensions: Anglo Settlers and Tejanos Unite

The growing discord was not just between Mexican officials and Anglo settlers, but also involved Tejanos—Mexican Texans who shared cultural ties to both communities. Their loyalties were complex, often torn between loyalty to the Mexican republic and a desire for greater local autonomy.

Both groups faced increasing pressure. The Mexican government abolished the federalist constitution of 1824, imposing a centralist constitution in 1835 that stripped Texas of its local rights. Trade restrictions, military occupation, and a crackdown on dissent inflamed passions that had been quietly smoldering.

Amid this turmoil, a unique alliance formed among settlers and Tejanos alike. This coalition sought not annihilation of Mexico but restoration of constitutional federalism, and finally, the right to self-government when negotiations failed.

4. The Spark of Rebellion: From Dissent to Declaration

The clashes began in earnest in 1835, with skirmishes at Gonzales—famously remembered for the “Come and Take It” cannon stand—and McKenzie’s conflicts. Texan leaders convened in several early meetings, balancing between loyalty to Mexico and the practical necessity of armed resistance.

As Mexican forces under Santa Anna marched to enforce his direct rule, many Texan leaders realized that compromise was no longer an option. The phrase “independence or death” entered the political lexicon with grave seriousness.

The march to Washington-on-the-Brazos for a constitutional convention was, in essence, a march toward sovereignty—a declaration that the old political order must yield to a new era.

5. Gathered at Washington-on-the-Brazos: The Convention Begins

About fifty delegates—farmers, lawyers, and businessmen—gathered in a wooden structure that is today memorialized as the birthplace of Texas independence. Not all were unanimous in outright independence; some favored continued resistance within a Mexican federalist framework.

Sam Houston, a towering figure of American frontier experience, and David G. Burnet were among the most prominent delegates, alongside draft authors such as George C. Childress.

The atmosphere buzzed with debate and tension. Outside, news filtered in of battles like the Alamo, which had sharpened the urgency of their task. The convention’s delegates moved quickly but carefully. The creation of a Declaration of Independence, a constitution, and the election of interim leaders all demanded attention.

6. Portraits of the Founding Fathers: Visionaries of Texas Independence

The individuals who composed this convention were far from homogeneous. Many were immigrants from states like Tennessee, Louisiana, and Kentucky; others were born in Mexico but loyal to the Texan cause.

George C. Childress, often considered the primary author of the Declaration, combined patriotism with legal acuity. Sam Houston, the seasoned soldier and politician, offered strategic direction and unflinching leadership. David G. Burnet became the interim president of the fledgling republic.

Their backgrounds, ideologies, and personalities mixed into a potent blend of determination and pragmatism, each understanding that the stakes were existential.

7. Drafting the Declaration: Language of Freedom and Resolve

Modeled partly on the American Declaration of Independence, the Texas Declaration was a document of striking clarity and passion. Carefully stating abuses by the Mexican government, it justified the choice of independence as a last resort.

Childress’ words highlighted grievances against Santa Anna’s dictatorship, including the dissolution of constitutional rights, the imposition of military rule, and the denial of due process.

The text resonated not only with legal principles but with the deep personal sacrifices the Texians were ready to endure. This was a birth cry for a new republic grounded in liberty and rule of law.

8. The Political Landscape: Republic or Annexation?

Even as independence was declared, questions loomed over what this new republic might become. Annexation by the United States was a persistent hope among many settlers, who looked southward for security and economic opportunity.

However, the prospect of annexation carried risks: potential war with Mexico, political controversies over slavery, and the fragile position of Texas as a territory with ambiguous boundaries.

The chosen path was to establish a sovereign republic, pending future decisions. Mexico would not recognize this independence, setting the stage for prolonged conflict.

9. The Immediate Aftermath: Responses from Mexico and the United States

Mexico’s reaction was swift and uncompromising. Santa Anna mobilized a massive force determined to crush the rebellion. This led to brutal confrontations: the Alamo siege, Goliad massacre, and the Battle of San Jacinto.

The United States government, meanwhile, adopted caution. Supporting Texan settlers informally and morally, it hesitated to ignite tensions with Mexico openly, caught between expansionist impulses and diplomatic restraint.

10. The Lone Star Emblem: Symbols of a New Nation

The symbolism of Texas independence quickly took hold. The Lone Star flag became an emblem of uniqueness, defiance, and hope.

This visual identity helped unify a diverse populace, providing not just rallying imagery but a statement of distinctiveness from the old governing powers.

11. Blood and Sacrifice: The Alamo and Goliad as Backdrops

While political leaders declared independence, the price of freedom was paid in blood. The heroic, ill-fated defense of the Alamo embodied the tragic determination of the Texian cause.

The massacre at Goliad, where surrendered Texan soldiers were executed by Mexican forces, further inflamed the struggle and deepened the resolve of the Republic’s defenders.

These events are inseparable from the declaration itself—reminders of the cost of liberty.

12. Samuel Houston’s Rising Command: Military and Moral Leadership

Sam Houston’s leadership transcended the battlefield. A man of complex background—former governor, soldier, and frontiersman—he became the symbol of Texan resilience and strategic sense.

His leadership culminated at the Battle of San Jacinto (April 21, 1836), where Texan forces routed Santa Anna’s army, securing effective independence.

Houston’s role was pivotal: he embodied the republic’s hopes, blending military strategy with political sensibility.

13. International Recognition: Challenges for a Nascent Republic

Despite the victory, international recognition was elusive. England and France watched cautiously, considering commercial interests but wary of Mexican reprisals.

The young republic had to navigate diplomacy carefully while consolidating governance and defending borders.

14. The Struggle for Governance: Early Republic Institutions and Policies

Newly declared, the Republic of Texas faced daunting tasks: creating legal systems, establishing a capital (initially Houston, later Austin), and managing relations with native tribes.

Political factions vied for influence, balancing expansionist dreams with pragmatic governance.

15. Economic Dreams and Realities: Land, Trade, and Expansion

Texas’ vast lands promised opportunity but also demanded infrastructure and investment. Trade opportunities beckoned, especially with the United States and Europe, but instability posed hurdles.

Land grants fueled immigration and speculation, sowing seeds for future growth and conflict.

16. The Role of Slavery: Controversies Within the Republic’s Foundations

A shadow lay beneath the young republic—slavery. Most Anglo settlers brought enslaved workers with them; the republic legalized slavery, aligning Texas with southern U.S. interests.

This contentious issue complicated negotiations with the U.S., Mexico, and indigenous peoples, shaping social and political fault lines.

17. Cultural Hybridization: Anglo and Tejano Identities Intertwined

Texas was a cultural crossroads. Anglo settlers and Tejanos shared the land, music, and sometimes faith—but conflicts ran deep.

The republic’s identity reflected both convergence and division, a story less told but integral to understanding its complexity.

18. The Republic’s Short but Turbulent Existence (1836-1845)

For nearly a decade, the Republic of Texas existed as a sovereign nation, despite continuous challenges: raids on frontiers, diplomatic limbo, and internal political strife.

From establishing a navy to funding its army, the republic fought for survival and recognition in an often hostile environment.

19. Annexation by the United States: Texas’ Complex Path

In 1845, Texas agreed to join the United States, a controversial and geopolitically explosive step.

This annexation contributed directly to the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), reshaping North America and sparking debates about slavery and expansion.

20. Legacy and Memory: How Texas Remembers March 2, 1836

Every year, Texans mark March 2 as Texas Independence Day with pride and ceremony. Monuments, reenactments, and stories sustain the memory.

This date remains a powerful symbol of identity, independence, and the frontier spirit.

21. Lessons from the Republic: Independence, Identity, and Power

The story of Texas’s independence speaks to universal themes: the quest for self-determination, the complexities of cultural conflict, and the fragile nature of young nations.

It reminds us how ideals clash with realities, and how courage can alter destinies.

Conclusion

The declaration of the Republic of Texas on March 2, 1836, stands as a defining moment where determination met destiny amidst an unforgiving frontier landscape. Men and women, settlers and natives, Mexicans and immigrants alike lived a story of resistance, hope, sacrifice, and vision. Their bold assertion of independence was as much about forging a new political order as about grasping a dream of liberty in a world that often refused it.

Though the republic itself lasted less than a decade, its impact reverberates through history—not only in the Lone Star State but across the narratives of freedom, conflict, and identity worldwide. That wooden hall at Washington-on-the-Brazos, alive with debate and courage, remains an eternal symbol: when people claim their right to self-rule, the course of history bends, sometimes violently, but always irrevocably.

FAQs

Q1: Why did the settlers in Texas want to declare independence from Mexico?

A1: The settlers were frustrated by Mexico’s move toward centralism, the abolition of local rights, restrictions on immigration, and especially the outlawing of slavery, which many settlers depended upon for their agricultural economy. The lack of political representation and increasing military presence further fueled the desire for independence.

Q2: Who were the key figures at the Convention of Washington-on-the-Brazos?

A2: George C. Childress was the principal author of the Declaration of Independence; Sam Houston was the military leader who later became the Republic’s president; David G. Burnet served as the interim president during the early days of the republic.

Q3: What role did Tejanos play in the Texas Revolution?

A3: Tejanos comprised Mexican Texans who often supported the independence movement, seeking protections for their own political rights and local governance. Their involvement was crucial in bridging cultural divides and lending legitimacy to the revolt against Santa Anna.

Q4: How did the United States react to the Republic of Texas’ declaration of independence?

A4: The U.S. government remained cautious initially due to diplomatic concerns over relations with Mexico and the contentious issue of slavery. However, many Americans sympathized with the republic, and informal support flowed. Eventually, the U.S. annexed Texas in 1845.

Q5: What were the consequences of Texas’ independence for Mexico?

A5: Mexico refused to recognize Texas’ secession and attempted to regain control by military means, leading to the Texas Revolution’s violent battles. This ultimately culminated in Mexico’s wider conflict with the U.S. during the Mexican-American War after Texas’ annexation.

Q6: How is March 2, 1836, commemorated today in Texas?

A6: It is celebrated as Texas Independence Day with ceremonies, parades, educational events, and historical reenactments that honor the bravery and vision of those who declared the republic.

Q7: Did the Republic of Texas have its own government and institutions?

A7: Yes, the Republic established a constitution, elected officials, a legal system, and even maintained an army and navy to defend its sovereignty until it was annexed by the United States.

Q8: What role did slavery play in the Republic of Texas?

A8: Slavery was legally sanctioned in the Republic of Texas, reflecting the social and economic practices of many settlers. This fact complicated its relationship with Mexico, which had abolished slavery, and was a significant issue in its later annexation to the U.S.