Table of Contents

- The Dawn of Industrial Power: London, 1698

- Thomas Savery: The Man Behind the Machine

- Unquenchable Thirst for Innovation: Early Steam Technology

- Water, Mines, and Desperation: The Challenges of 17th-Century Mining

- Conception of the "Miner’s Friend": Inspiration and Design

- The Savery Steam Pump: How It Worked

- The Patent of 1698: A Legal Victory and a Symbol of Progress

- Early Trials and Tribulations: Practical Use and Limitations

- The Pump in Action: Transforming Coal Mines and Beyond

- Rivalry and Rival Innovations: Newcomers to the Steam Scene

- Society’s Reaction: From Skepticism to Awe

- Economic Ripples: The Pump’s Effect on Mining and Industry

- The Lineage of Steam Engines: Savery’s Place in History

- Quenching the Fires of Industry: Boiler Explosions and Safety Concerns

- Why Savery’s Pump Did Not Last: Technical and Practical Challenges

- Transition to New Steam Technologies: Newcomen’s Engine Emerges

- The Cultural Resonance: Steam Power and the Birth of the Industrial Revolution

- The Global Echoes: How Savery’s Invention Crossed the Seas

- Literature, Art, and Steam: The Machine as Muse

- The Legacy Preserved: Museums, Models, and Memories

- Conclusion: From a London Workshop to the Engines of Modernity

- FAQs: The Questions That Continue to Fascinate

- External Resource

- Internal Link

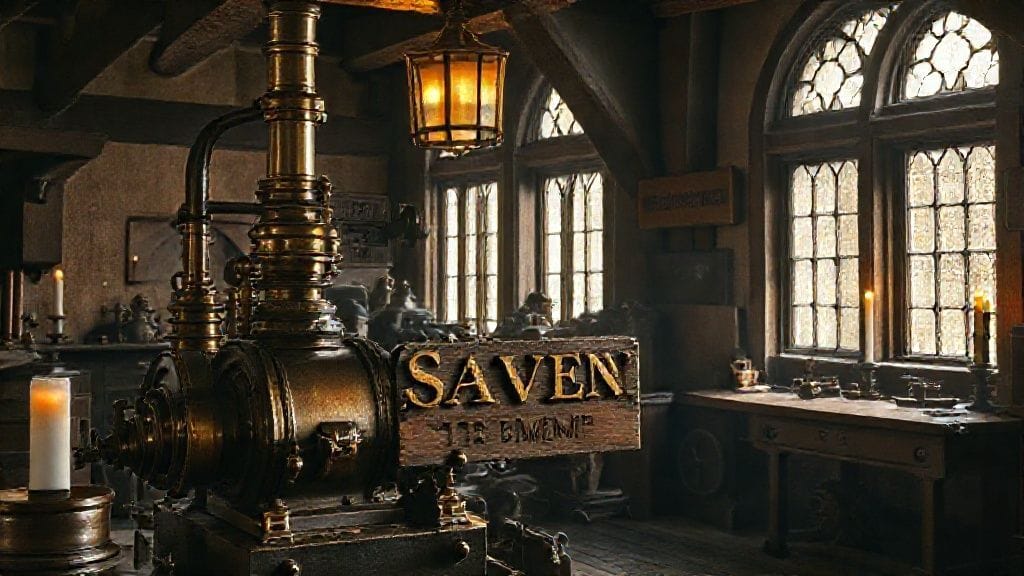

1. The Dawn of Industrial Power: London, 1698

On a cold January morning in 1698, the bustling streets of London whispered a secret of transformation. Amid the clamor of horse-drawn carriages and merchants haggling along the Thames, beneath the fog and soot, an invention quietly emerged that would power humanity into a new age. It was not yet a roaring giant of iron and fire but a curious contraption—a steam-driven pump, unlike anything seen before. Thomas Savery’s brainchild promised to wrest water from the depths of flooded mines, a problem plaguing English industry for centuries. As the first hiss and pulse of steam escaped the iron vessel, it was as if the city itself held its breath, unaware that the invention it bore would ignite the Industrial Revolution.

2. Thomas Savery: The Man Behind the Machine

To understand the Savery steam pump is to understand its creator—Thomas Savery. Born in Devon, England, in 1650, Savery was a military engineer turned inventor whose curiosity burned as fiercely as the coal that fueled his invention. Though not a master of metals or mechanics by the strictest measure, Savery’s genius lay in his unyielding determination to solve a practical problem: the dangerous, costly, and often deadly flooding of mines. Like many innovators, his life was a union of trial and error, tinkering and theory, until the moment his device emerged. A man navigating the crossroads of scientific revolution and burgeoning capitalism, Savery embodied the restless spirit of his time.

3. Unquenchable Thirst for Innovation: Early Steam Technology

The 17th century was marked by an extraordinary thirst for discovering the secrets of nature and harnessing its power. Steam, though observed in natural geysers and rudimentary devices, had yet to be tamed. The science of thermodynamics was absent, and yet inventors such as Savery dared to use boiling water’s invisible energy to perform palpable work. Before his pump, early devices like the aeolipile by Hero of Alexandria had puzzled scholars for centuries but remained curiosities. Savery’s innovation shifted steam’s role from spectacle to tool, laying foundations that would later be built upon by engineers like Newcomen and Watt. Steam was no longer just vapor but a force.

4. Water, Mines, and Desperation: The Challenges of 17th-Century Mining

Mining was one of England’s economic pillars, especially for coal and metals essential to burgeoning industries and crafts. Yet, beneath the earth, an endless menace lurked—water. Mines flooded with liquid, stalling extraction and endangering lives. The traditional methods—hand pumps and buckets—were rudimentary and labor-intensive. Venturing deeper into the bowels of the earth made this problem worse. The flooding not only threatened individual miners but also strangled the supply lines for fuel and raw materials. The stakes were colossal, and every year of struggle drained profits and hope. The demand for an effective pump was urgent, perhaps desperate.

5. Conception of the "Miner’s Friend": Inspiration and Design

Savery’s solution was as elegant as it was revolutionary. Drawing from the expansive body of knowledge of the time—thermodynamics unknown but steam understood empirically—he conceived a pump that used steam pressure and vacuum to raise water. Dubbed the “Miner’s Friend,” the invention was essentially a closed vessel where water was driven upward by steam force and suction. It was unlike any pump before; it did not use a piston but an ingenious system of valves and chambers. Savery’s sketches reveal a mind bridging practicality and innovation, a design that could be manufactured with contemporary materials and craftsmanship. Yet, this simplicity masked complexity.

6. The Savery Steam Pump: How It Worked

At its core, the pump exploited the expansion of steam and subsequent condensation to generate suction and pressure. First, steam was introduced into the pump’s vessel, expelling water through an outlet pipe. Then, cold water cooled the steam inside, creating a vacuum that sucked water into the chamber from the mine. The steam was then reintroduced to force the water upwards. This cycle repeated, lifting water to higher ground. Remarkably, this process required no moving pistons or complex machinery, making it simpler and more reliable in theory than later engines. However, despite this, the device had inherent limitations, especially under high pressure, which would eventually limit its widespread success.

7. The Patent of 1698: A Legal Victory and a Symbol of Progress

On June 14, 1698, Thomas Savery was granted a patent by King William III—the patent number 1,533—in a ceremony that highlighted the economic and political significance of the invention. This event was not just a bureaucratic formality but a public acknowledgment that steam power was a national interest. The patent covered the use of “fire engines” for raising water and described the potential vast applications of such mechanisms beyond mines—firefighting and water supply for towns. This legal consecration propelled Savery into the limelight but also sparked a race among inventors and entrepreneurs eager to develop or improve the technology.

8. Early Trials and Tribulations: Practical Use and Limitations

Despite the excitement, the pump’s introduction to the field was met both with praise and frustration. It was successfully deployed in some shallow English coal mines, lifting water from depths of up to 32 meters—beyond which pressure limitations became hazardous. Engineers found it difficult to maintain the high-pressure boilers safely, and explosions sometimes occurred. Furthermore, the pump required a steady supply of fuel to boil the water, posing economic challenges. Still, mine owners willing to invest saw it as a gradual solution, in contrast with laborious manual methods. Early reports spoke of improved mine drainage and savings, yet the technology was not yet mature enough to replace all existing methods.

9. The Pump in Action: Transforming Coal Mines and Beyond

In practice, Savery’s pump made early inroads in coal mining regions around Newcastle and Cornwall, where water had been a persistent adversary. Though not infallible, it allowed miners to extend excavations previously impossible. With the ability to drain water more efficiently, coal extraction increased, providing more fuel to urban centers hungry for warmth and industry. It also opened doors to broader applications—some towns experimented with firefighting uses. This pioneering step paved the way for a conceptual shift—machines could now do what men and animals did laboriously. It was a hint of the mechanized future, even as the engine itself remained a niche tool.

10. Rivalry and Rival Innovations: Newcomers to the Steam Scene

Yet, the story was far from over. The limitations of Savery’s pump—particularly the dangers of high-pressure steam and its inefficiency—sparked other engineers to seek alternatives. Thomas Newcomen, around 1712, introduced the atmospheric engine, which borrowed from Savery’s principles but incorporated a piston and cylinder, vastly improving performance and safety. This rivalry was not mere competition but the engine of progress. Where Savery had laid the groundwork, Newcomen advanced, and later James Watt revolutionized steam power further in the 18th century. Each step represented a leap, building on the last invention’s successes and failures.

11. Society’s Reaction: From Skepticism to Awe

Initially, many viewed Savery’s pump with skepticism. Steam power was a mysterious and sometimes feared force. The idea of using “fire and vapor” to move water confounded traditional thinkers. Yet, the technology’s promise could not be ignored. Mining communities cautiously adopted it, and local newspapers began recounting its feats and failures. Craftsmen and engineers who once relied solely on muscle and manual tools now engaged with the language of valves and boilers. This transition signaled a broader cultural shift—towards embracing machines as partners in labor. It was a time of awe, debate, and tentative acceptance, mirroring the tensions of scientific revolution more broadly.

12. Economic Ripples: The Pump’s Effect on Mining and Industry

Economically, the pump was a modest but crucial catalyst. By enabling deeper mining, it indirectly increased coal availability, the cornerstone of countless industries and domestic life. Rising coal output fueled iron production, glassmaking, and heating, all pivotal for England’s emerging industrial fabric. The device also introduced new commercial dynamics—boiler and pump manufacturing, engineering services, and fuel supply chains grew in importance. Investors saw the potential in mechanization’s efficiencies. While Savery’s pump alone did not spark the Industrial Revolution, it became a symbol and foundation for the economic transformations soon to explode.

13. The Lineage of Steam Engines: Savery’s Place in History

Historians often view Savery’s steam pump as the seed from which the tremendous tree of industrial steam power grew. It represented the first real, working harnessing of steam for mechanized pumping. Though soon outpaced by later developments, Savery’s engine was a necessary precursor. Its design, patenting, and practical application established steam’s legitimacy as an industrial force. Without Savery, the atmospheric and later Watt steam engines might have arrived decades later, hindering the flow of coal and iron essential to mechanized industry. Thus, he remains an unsung pioneer—one foot in alchemy, the other in engineering.

14. Quenching the Fires of Industry: Boiler Explosions and Safety Concerns

Behind the idealism of invention lurked darker realities—Savery’s pump ran under high pressure, operating boilers that were prone to failure. Early 18th-century metallurgy and safety standards were primitive, making explosions commonplace and deadly. These disasters fostered fear and resistance among laborers and investors. Governments and private owners recognized that steam machines required regulation and skilled maintenance. The dangers underscored an essential lesson of industrialization: innovation is fraught with risk. Yet, these fires and failures sparked improvements in boiler construction, leading to more robust, safer technology by the century’s middle.

15. Why Savery’s Pump Did Not Last: Technical and Practical Challenges

Despite its groundbreaking nature, the pump was hampered by intrinsic flaws: its limited lifting capacity (about 32 feet), the dangers of high-pressure steam, and its inefficiency compared to later engines. It was incapable of pumping water from very deep mines or sustaining continuous operation without frequent maintenance. In addition, the lack of a piston meant lower precision and control. Consequently, mine owners often preferred Newcomen’s piston engine when available. The pump’s design was rapidly eclipsed, yet this swift obsolescence should not diminish its pioneering value. It was the first step in a progression that transformed the world.

16. Transition to New Steam Technologies: Newcomen’s Engine Emerges

By the early 18th century, Thomas Newcomen built upon Savery’s concepts, introducing a piston and cylinder where atmospheric pressure would fill roles Savery’s pump could not. His engine was safer and could drain mines at greater depths. This evolution was crucial, turning steam into a more versatile industrial tool. Newcomen’s engine became widespread in mining and beyond, operated for nearly a century. Eventually, James Watt’s improvements focusing on efficiency and rotation would transform it into the powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution. Savery’s pump was the dawn; Newcomen’s engine was the sunrise.

17. The Cultural Resonance: Steam Power and the Birth of the Industrial Revolution

Steam power quickly transcended mere utility to shape cultural and intellectual life. It appeared as a marvel in literature, symbolizing progress, human mastery over nature, and the tension between tradition and modernity. Artists, writers, and philosophers grappled with the implications of mechanization—the dawn of new human possibilities but also alienation and risk. The steam pump stood at the intersection of these debates, a potent emblem of the coming industrial world that would remap social structures, economies, and daily life. Its invention resonated beyond mining, touching every facet of early modern England’s psyche.

18. The Global Echoes: How Savery’s Invention Crossed the Seas

Though initially an English invention, the ideas embodied in Savery’s steam pump quickly traveled. European engineers studied it; American colonies saw its utility for mining and water supply. Eventually, as steam technology matured, it became a pillar of global industrial infrastructure—from British factories to American railroads. The pump’s direct design spread less than its conceptual breakthrough—the harnessing of steam for practical labor. It thus catalyzed a worldwide technological shift, a thread weaving through the fabric of early industrial connectivity, commerce, and empire.

19. Literature, Art, and Steam: The Machine as Muse

Steam power, beginning with inventions like Savery’s pump, inspired countless artistic expressions. From metaphoric poems portraying steam as Prometheus’s fire to engravings showing smoky factories and gleaming engines, the machine became a symbol of human ambition and anxiety. Contemporary journals and academic treatises dissected the invention’s novelty, sometimes with poetic flourish. This fusion of art and technology underscored the deep hold steam had on the collective imagination—celebrated for progress, lamented for disruption, and forever admired for its power.

20. The Legacy Preserved: Museums, Models, and Memories

Today, remnants of Savery’s steam pump survive in museums and preserved papers. Models built by engineers and historians allow us a tangible interaction with his invention. Exhibitions in London, Newcastle, and beyond commemorate this humble engine’s role in setting industrial history in motion. Savery’s name, once overshadowed by Newcomen and Watt, is reemerging as historians rediscover the importance of his contribution. In a world increasingly conscious of heritage, the pump is a testament to human ingenuity and persistence.

21. Conclusion: From a London Workshop to the Engines of Modernity

When Thomas Savery released his steam pump onto the laboring world in 1698, he unwittingly opened a door to the future. It was not yet the grand, iron heart of industry, but a delicate step into uncharted territory. His invention faced technical and practical limits, dangers and doubts, yet it laid the groundwork for a centuries-long transformation. The Industrial Revolution, fueled by steam, forever altered economies, societies, and cultures—beginning in a London workshop with Savery’s “Miner’s Friend.” His legacy is a reminder that every revolution begins with a simple, brave idea, steam rising slowly from a humble iron vessel.

Conclusion

In retrospect, the invention of the Savery steam pump stands as a monumental milestone in the annals of industrial history. It bridged centuries of mechanical ignorance and heralded a new era where steam, an invisible and mysterious force, found practical mastery to serve human needs. Although its technology soon gave way to improvements and superior engines, Savery’s pump was the spark in Britain’s—and the world's—journey toward industrial modernity. Beyond mechanics, it stimulated society to think differently about work, power, and progress. The rattling hiss of steam in 1698 was not just noise—it was the sound of an epoch being born.

FAQs

Q1: What motivated Thomas Savery to invent his steam pump?

A1: Savery was driven by the urgent challenge of water flooding in mines, which caused financial losses and hazards to miners. His military engineering background and interest in practical solutions fueled his invention.

Q2: How did Savery’s steam pump differ from earlier steam devices?

A2: Unlike earlier devices that demonstrated steam’s properties without practical use, Savery’s pump applied steam pressure and vacuum cycles to pump water, making it the first functional steam-powered machine for industrial work.

Q3: Why was the pump called the “Miner’s Friend”?

A3: Because it was designed specifically to remove water from flooded mines, greatly assisting miners by reducing the need for manual extraction and enabling deeper mining operations.

Q4: What were the main limitations of Savery’s steam pump?

A4: The pump was limited in lifting height (about 32 feet), relied on high-pressure steam which posed safety risks, and lacked a piston mechanism, making it less efficient for deep or continuous pumping.

Q5: How did the invention influence future steam engines?

A5: Savery’s device demonstrated the practical use of steam pressure and vacuum in machinery, inspiring inventors like Newcomen and Watt to develop more efficient and safer steam engines.

Q6: What was the social reaction to the pump’s introduction?

A6: Society responded with a mix of skepticism, fear due to boiler explosions, and admiration for the technological breakthrough. It signaled changing attitudes toward mechanization and industrial labor.

Q7: Did Savery’s steam pump have uses beyond mining?

A7: Yes, Savery proposed applications such as firefighting and water supply for towns, though its practical use was mostly limited to mining due to technical constraints.

Q8: Where can one learn more about the Savery steam pump?

A8: The Savery steam pump is documented extensively through patents, engineering histories, and museum displays. Online platforms like Wikipedia and History Sphere offer detailed resources.