Table of Contents

- The Final Days of a Great Emperor: Shah Jahan in Agra

- Setting the Stage: The Mughal Empire in the Mid-17th Century

- Shah Jahan’s Reign: Triumphs and Tribulations

- The Burden of Power: Health, Succession, and Shadows

- The Imperial Palace: A Prison and Sanctuary

- The Last Breath: Shah Jahan’s Death on January 22, 1666

- Agra’s Silent Mourning: Public and Court Reaction

- The Legacy of the Peacock Throne

- Aurangzeb’s Ascendancy: Fraternal Struggle and Succession Wars

- The Mausoleum as a Monument: Legacy in Stone

- Changing Tides: Mughal India After Shah Jahan

- The Cultural Flourish under Shah Jahan: Poetry, Architecture, and Art

- Political Intrigue and Familial Discord: Seeds of Decline?

- Shah Jahan in Historical Memory and Popular Imagination

- The Global Impact of Mughal India’s Golden Age

- Reflecting on Mortality: Kings and Time in the Mughal Era

- The Preservation of History: Sources and Mythologies

- A Sultan’s End and a New Era’s Dawn

- Conclusion: The End of an Epoch, The Beginning of Legends

- FAQs: Unraveling the Mysteries of Shah Jahan’s Death and Legacy

- External Resource

- Internal Link

The Final Days of a Great Emperor: Shah Jahan in Agra

The cold January air wrapped itself around the marble walls of the Red Fort in Agra, where the fading figure of Shah Jahan lay on his deathbed. The great emperor who had once commanded armies and commissioned the world’s most breathtaking monument—the Taj Mahal—faced the inexorable tide of mortality. His breath grew shallow, each inhale a labor, his mind drifting through the hallways of memory and empire. Outside, the city of Agra seemed frozen in time, shadows cast long and somber beneath the winter sun. It was January 22, 1666, a date that marked the silent fall of an era.

The death of Shah Jahan was not merely the passing of a man; it was the closing of a chapter in the grand and opulent story of Mughal India. It carried the weight of political intrigue, familial grief, and cultural transformation. The emperor who had ruled at the zenith of Mughal brilliance now became a figure of reflection and dramatic transition.

Setting the Stage: The Mughal Empire in the Mid-17th Century

To understand the significance of Shah Jahan’s death, one must first travel back into the complex fabric of 17th-century Mughal India. The empire, sprawling across much of the subcontinent, was a mosaic of cultures, languages, and religions, bound together by the iron hand of imperial order and the intricate dance of court politics.

Shah Jahan, born Prince Khurram in 1592, ascended to the throne in 1628 succeeding his father Jahangir. This period was marked by unprecedented architectural and artistic achievements but also underlying tensions—within the royal family, the court nobility, and the growing centrifugal forces in the provinces.

The emperor’s reign had been a paradox: military campaigns that expanded borders interlaced with internal strife, rich patronage of arts shadowed by ruthless suppression of dissent. By the mid-1660s, the empire faced the twin challenges of succession disputes and external pressures from the Deccan Sultanates and emerging European powers.

Shah Jahan’s Reign: Triumphs and Tribulations

Shah Jahan’s nearly four-decade reign was the epitome of Mughal opulence and power. His most famous legacy—the Taj Mahal—stands as both a testament to his love for his wife Mumtaz Mahal and a symbol of imperial grandeur.

Yet, beneath the elegant courts and monumental architecture lay a web of intrigue. The emperor was as much a visionary patron as he was a stern and occasionally ruthless ruler. His campaigns in the Deccan and against rebellious nobles demonstrated a will to maintain central authority, but they left the empire exhausted.

Sidelined by his own faltering health in his later years, Shah Jahan found himself enveloped in family conflicts, particularly with his sons vying for power. Aurangzeb, his third son, was increasingly assertive and ambitious.

The Burden of Power: Health, Succession, and Shadows

In the twilight of his life, Shah Jahan was a man burdened not just by age and illness but by the looming threat of dynastic conflict. His health deteriorated amid the relentless pressures of maintaining imperial authority and managing the ambitions of his four sons.

The power struggle had erupted violently in earlier years, with Aurangzeb imprisoning Shah Jahan in Agra’s Red Fort in 1658 after seizing the throne. The emperor spent his last days confined within familiar palatial walls, a prisoner in the very empire he built.

This paradoxical existence—both emperor and captive—shaped the atmosphere around his deathbed.

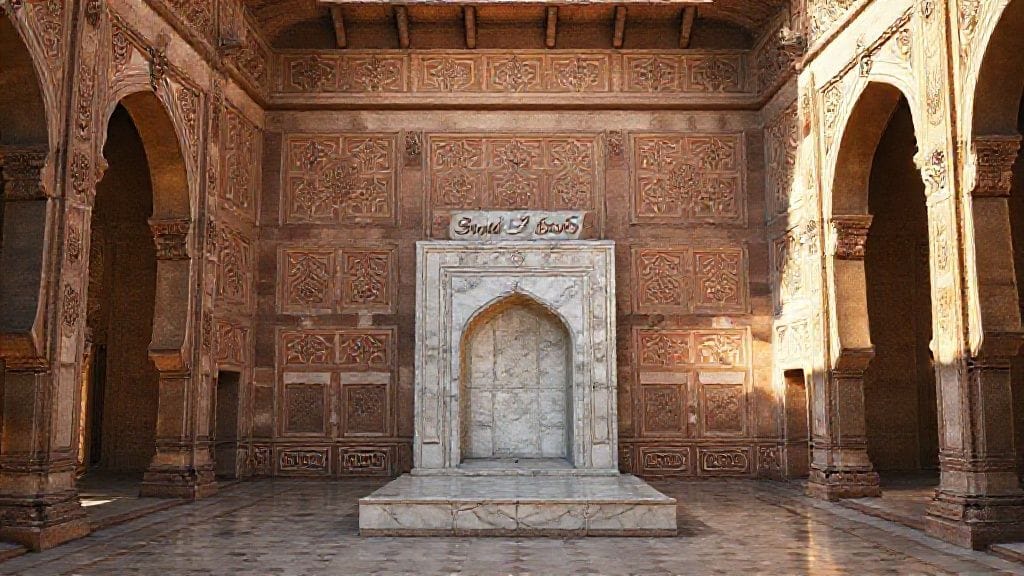

The Imperial Palace: A Prison and Sanctuary

The Red Fort in Agra, with its intricate gardens, domed pavilions, and ivory-white marble halls, was both a luxurious refuge and a gilded cage for Shah Jahan. Captured by his son Aurangzeb’s political machinations, the emperor’s imprisonment was cruel but dignified.

From behind the latticed windows of the Pearl Mosque (Moti Masjid), Shah Jahan gazed at the Taj Mahal, his beloved wife’s mausoleum, the monument that symbolized both his deepest love and the fragility of his reign.

In these final moments, the opulence of the Mughal court contrasted starkly with the somber reality of the dying ruler.

The Last Breath: Shah Jahan’s Death on January 22, 1666

As the dawn light pierced through the red sandstone corridors, Shah Jahan’s life ebbed quietly. His breathing slowed; his eyes closed to the world he helped shape. The court officials and eunuchs who surrounded him wept silently, aware that the empire’s heartbeat was forever altered.

His death was mourned with great solemnity, not just as the loss of a sovereign but as the extinguishing of a luminary whose vision had defined an age.

Yet his passing was only the prologue to further upheavals, as Aurangzeb’s reign would veer sharply away from his father’s legacy.

Agra’s Silent Mourning: Public and Court Reaction

News of Shah Jahan’s death spread across Agra and then reverberated through the Mughal territories. The public response was one of reverence mingled with apprehension. Processions and prayers filled the city as people grappled with the enormity of losing a ruler whose architectural masterpieces graced every horizon.

In the imperial court, while outward displays of loyalty prevailed, machinations simmered anew. Aurangzeb’s consolidation of power was absolute, but the empire’s soul seemed to mourn the passing of its golden age.

The Legacy of the Peacock Throne

Beyond the man himself, Shah Jahan’s reign is often epitomized by the legendary Peacock Throne—a dazzling symbol of imperial majesty encrusted with jewels that dazzled foreign envoys. Commissioned by Shah Jahan in the early 17th century, it embodied the wealth, artistry, and prestige of the Mughal court.

With the emperor’s death, the throne became a contested emblem, emblematic of both the empire’s splendour and its fragility in the face of internal conflict and external threats.

Aurangzeb’s Ascendancy: Fraternal Struggle and Succession Wars

The death of Shah Jahan sealed Aurangzeb’s position as emperor, a rule marked by stark contrasts with his father. Aurangzeb’s austere policies, religious conservatism, and military expansions shifted the trajectory of Mughal India dramatically.

The fraternal wars with his brothers—Dara Shikoh, Shah Shuja, and Murad Baksh—had drained the empire’s resources and left bitter scars. Aurangzeb’s iron-fisted rule ushered in both the heightening of imperial control and the seeds of decline.

The Mausoleum as a Monument: Legacy in Stone

Ever since its completion in 1653, the Taj Mahal was more than a tomb; it was a declaration of eternal love and power. Shah Jahan’s death transformed it into an even more poignant symbol—a final resting place as well as an architectural wonder.

Historians, poets, and travelers have marveled at this dolorous masterpiece that encapsulates the interplay of life, love, death, and memory in Mughal India.

Changing Tides: Mughal India After Shah Jahan

The post-Shah Jahan era was characterized by shifting allegiances, growing internal dissent, and the gradual encroachment of European colonial powers. The empire that had shone so brightly was beginning to flicker.

The death of an emperor who embodied the zenith of Mughal culture in many ways marked the acceleration of political and social changes that would transform the subcontinent in the centuries to come.

The Cultural Flourish under Shah Jahan: Poetry, Architecture, and Art

Though his death signaled an end, Shah Jahan’s reign was a golden age of Mughal culture. From the fusion of Persian and Indian motifs in buildings to the flourishing of miniature painting and Urdu poetry, this cultural efflorescence left a permanent imprint.

His patronage attracted some of the greatest artists and thinkers of his time, making the Mughal court a beacon of sophistication.

Political Intrigue and Familial Discord: Seeds of Decline?

However, the brilliance of Shah Jahan’s empire masked its internal fragility. The rivalries among his sons were not mere personal vendettas but reflected deeper fissures within the imperial structure.

His confinement by Aurangzeb, combined with escalating military expenditures, signs of weakening provincial loyalty, and religious strife, hinted at the vulnerabilities beneath grandeur.

Shah Jahan in Historical Memory and Popular Imagination

Over centuries, Shah Jahan has been immortalized as the quintessential “Great Mughal” and romanticized as the embodied love behind the Taj Mahal. Folklore, ballads, and literature have kept his memory alive, blending fact and myth.

Yet historians continue to probe the complexities of his reign—the blend of tyranny and tenderness, ambition and artistry.

The Global Impact of Mughal India’s Golden Age

Shah Jahan’s death and reign belong not only to Indian history but to the global story of empire, culture, and exchange. The Mughal empire was a hub of global trade, artistic exchange, and diplomacy linking Europe, Central Asia, and the Indian Ocean.

The legacies of Mughal architecture and statecraft influenced other regions, while shifting European interests set the stage for colonial conquest.

Reflecting on Mortality: Kings and Time in the Mughal Era

Shah Jahan’s death invites a broader meditation on the nature of power and mortality. The emperor who defied time through stone was, in the end, just as mortal as the peasants and courtiers who lived under his rule.

His passing is a reminder of the ephemeral nature of glory and the enduring cycle of rise and fall in human affairs.

The Preservation of History: Sources and Mythologies

Our understanding of Shah Jahan’s death and reign comes from a rich array of sources—court chronicles, European traveler’s accounts, Persian poetry, and architectural testimonies.

Yet these sources are filtered through political agendas and cultural lenses that historians must read with care to reconstruct a nuanced picture.

A Sultan’s End and a New Era’s Dawn

The death of Shah Jahan closed one chapter and opened another. Aurangzeb’s long reign would eventually weaken the empire, but the echoes of Shah Jahan’s grandeur would continue to inspire.

In death, as in life, Shah Jahan remains a figure of grandeur and tragedy—a monarch whose vision helped shape the tapestry of Indian history.

Conclusion

The death of Shah Jahan on that cold January day in 1666 was more than the quiet passing of a ruler; it was the symbolic closing of the Mughal empire’s most illustrious chapter. From his youthful ascension to his twilight years imprisoned within his own fort, Shah Jahan’s life mirrored the whirlwind of passion, power, artistry, and struggle that defined his era.

His magnificent constructions, especially the Taj Mahal, stand as eternal reminders of an empire’s zenith—where love intertwined with statecraft, where beauty was a tool of power, and where history was etched into marble. Yet, that grandeur was accompanied by family betrayals, wars of succession, and the slow unraveling of an empire that had ruled with almost divine authority.

His death marked the end of a golden age and the dawn of a more austere and turbulent period under Aurangzeb’s long shadow. But the human story of Shah Jahan endures—his dreams and despairs, his beauty and brutality—and through this, we glimpse the complex souls behind the empires that shaped our world.

FAQs

Q1: What caused Shah Jahan’s death?

A1: Shah Jahan died of natural causes after a period of declining health at the age of 74. By then, he was already imprisoned by his son Aurangzeb and spent his final years confined within Agra’s Red Fort.

Q2: How did Shah Jahan’s death affect Mughal succession?

A2: His death solidified Aurangzeb’s position as Mughal emperor, following a violent struggle among Shah Jahan’s sons. Aurangzeb’s ascendance led to major shifts in policy and the empire’s later decline.

Q3: Did Shah Jahan witness the completion of the Taj Mahal?

A3: Yes, the Taj Mahal was completed in 1653, well before Shah Jahan’s death. He reportedly spent his imprisonment gazing upon it, reflecting on his lost love and reign.

Q4: What was Shah Jahan’s relationship with his sons?

A4: It was fraught with rivalry and tragedy. Despite being a devoted father, political ambitions drove his sons Aurangzeb and Dara Shikoh into fratricidal conflict, eventually leading to Shah Jahan’s imprisonment.

Q5: How is Shah Jahan remembered in India today?

A5: Shah Jahan is celebrated as a patron of the arts and architecture, especially as the creator of the Taj Mahal. However, historians acknowledge the complexity of his reign, noting both achievements and the seeds of decline.

Q6: What impact did Shah Jahan’s death have on Mughal art and culture?

A6: While Shah Jahan’s death marked the end of a cultural golden age, his patronage ensured a lasting legacy in architecture, poetry, and art that continued to influence Mughal and Indian culture.

Q7: How reliable are the historical accounts of Shah Jahan’s final years?

A7: Accounts vary, often shaped by political biases of the time and later historians. Mughal court chronicles tend to emphasize his piety and grandeur, while European travelers provide external perspectives.

Q8: What role did the city of Agra play in Shah Jahan’s death?

A8: Agra was the imperial capital and site of his imprisonment and death. The city was deeply entwined with his reign, housing iconic palaces, the Red Fort, and the Taj Mahal.