Table of Contents

- The Dawn of Hope: A Small Village in Gloucestershire, May 1796

- The Scourge of Smallpox: A Global Menace

- Edward Jenner: A Physician Ahead of His Time

- Seeds of Innovation: From Folk Wisdom to Scientific Method

- The Patient: James Phipps, A Child at the Heart of History

- The First Inoculation: May 14, 1796 – A Moment Charged with Promise

- Testing the Boundaries: The Second and Third Stages of Jenner’s Experiment

- The Risks and Skepticism: A Dangerous Gamble in Medical History

- The Mechanisms of Vaccination: Understanding Cowpox’s Protective Shield

- Early Reactions: Support, Doubt, and Controversy in the Medical Community

- The Spread of Vaccination: From Gloucestershire to the World

- The Human Toll: How Jenner’s Discovery Saved Millions

- Smallpox Eradication: A Victory Forged Over Centuries

- The Legacy of the Smallpox Vaccine: Foundations of Modern Immunology

- Ethical Reflections: Testing on Humans and Medical Progress

- Jenner’s Personal Struggles and Triumphs

- The Socio-Political Impact: Public Health, Trust, and Resistance

- Anecdotes from the Field: Stories of Vaccination’s Early Days

- Statistical Proof: Data and Demonstrations of Efficacy

- Beyond Smallpox: How Jenner’s Work Inspired Future Vaccines

- The Modern Perspective: Smallpox Eradication in the 20th Century

- Cultural Memory: How Jenner’s Vaccine Changed Society’s View of Disease

- Conclusion: The Triumph of Science and Humanity

- Frequently Asked Questions About the Smallpox Vaccine’s First Test

- External Resource

- Internal Link

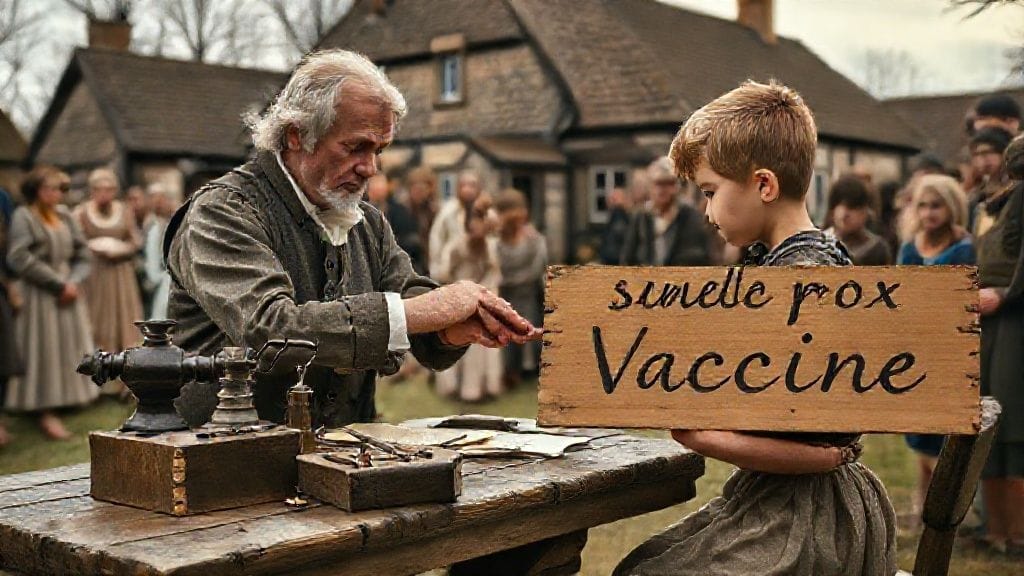

The Dawn of Hope: A Small Village in Gloucestershire, May 1796

The morning of May 14, 1796, dawned cool and crisp over the gentle hills of Gloucestershire, England. In the modest village of Berkeley, an unusual sense of anticipation stirred within the quiet walls of a local home. There, a young boy named James Phipps was about to become a pivotal figure in humanity’s battle against one of its oldest and deadliest foes: smallpox. Far from grandeur and scientific apparatus, a simple act of inoculation would set in motion a revolution that would alter the course of medicine and human survival forever. This was no ordinary day; it was the day of the world’s first smallpox vaccine test.

The Scourge of Smallpox: A Global Menace

For centuries, smallpox had been a relentless reaper, its pustules and fever wreaking havoc across continents. It did not discriminate, reducing emperors, peasants, and children alike to suffering and often death. The virus—variola major—spread rapidly, with mortality rates up to 30%, and left survivors scarred and blinded. Europe in the 18th century was obsessed and terrified by its annual outbreaks. Traditional methods of "variolation"—deliberate infection with smallpox material to induce immunity—brought some protection but also carried serious dangers, including death itself.

The stage was set for a breakthrough that could unmoor this atrocity from human fate. Scientific progress stumbled against centuries of superstition and risk. Yet hope flickered within the youthful enthusiasm and methodical mind of an English country doctor.

Edward Jenner: A Physician Ahead of His Time

Edward Jenner, son of a local vicar and raised amid the rural landscapes of Gloucestershire, emerged as an unlikely hero. His curiosity was fueled not only by books but by keen observation. Jenner had taken note of a peculiar folk belief: milkmaids who had caught cowpox, a mild disease contracted from cows, seemed immune to smallpox. Was there truth in this local wisdom, long dismissed by learned men?

By 1796, Jenner was deeply absorbed with the idea that cowpox could be a safer alternative to variolation. Educated but practical, he was a man convinced that observation must meet experimentation—a scientist of the Enlightenment spirit working in England’s agrarian heartland. The challenge was not only scientific but political and societal, fraught with skepticism and ethical quandaries.

Seeds of Innovation: From Folk Wisdom to Scientific Method

The idea was simple, yet bold: introduce the cowpox virus into a human to induce immunity, avoiding the deadly effects of smallpox. Jenner did not undertake this lightly. Prior to testing on James Phipps, the son of his gardener, Jenner considered safety and the implications of exposing a child to disease.

This was no mere trial but a calculated gamble, stepping into uncharted territory where science and humanity intersected. While Jenner had no concept of immunology as we understand it today, his methodical application of testing, observation, and documentation set new standards for medical research.

The Patient: James Phipps, A Child at the Heart of History

James Phipps was an unassuming child, unaware of the monumental role he would play. At just eight years old, he was selected for Jenner’s experiment — a decision that would spark debate for centuries over medical ethics but whose outcome would prove undeniably pivotal.

On May 14, Jenner took material from a cowpox sore on the hand of Sarah Nelmes, a milkmaid known to have contracted cowpox. With gentle precision, Jenner inoculated Phipps by scratching the boy’s arm and inserting the cowpox fluid. What followed was a careful vigil, watching for any signs of illness or protection—a wait as much charged with anxiety as hope.

The First Inoculation: May 14, 1796 – A Moment Charged with Promise

The days following the first inoculation saw young James Phipps develop a mild fever and localized inflammation—a far cry from the ravages of smallpox. Jenner documented every symptom meticulously, his heartbeat for a breakthrough palpable in each note.

But the true challenge lay ahead: could this cowpox “injection” protect Phipps from the real smallpox virus? Months later, Jenner would expose the boy to material from a fresh smallpox pustule. Against all expectation and fear, James Phipps remained healthy and unscarred. The world’s first successful vaccination, or “vaccine” derived from “vacca,” the Latin for cow, had been achieved.

Testing the Boundaries: The Second and Third Stages of Jenner’s Experiment

Jenner’s journey did not end with one success. He repeated the procedure on other subjects, typically children or young adults, carefully documenting reactions and protective effects. The method, though simple, became increasingly sophisticated as Jenner reinforced the concept of induced immunity.

Each new inoculation, however, invited both hope and heightened risk. The stakes could not have been higher—lives hung in the balance, and Jenner’s reputation was intertwined with these outcomes. Word spread slowly; each clinical case added weight to this humble beginning, gradually weaning the medical world from the old and dangerous variolation.

The Risks and Skepticism: A Dangerous Gamble in Medical History

The smallpox vaccine’s first test was as perilous as it was revolutionary. Jenner risked accusations of quackery, charges of recklessness, and the very real possibility of causing harm. Medical orthodoxy was deeply entrenched, and some contemporaries viewed Jenner’s method with suspicion—was this cowpox material truly safer?

Moreover, ethical questions arise when we consider the use of children like James Phipps for experimental inoculation. Jenner’s risk, however, was balanced by the absence of any alternative interventions and the terrifying toll of smallpox itself.

The Mechanisms of Vaccination: Understanding Cowpox’s Protective Shield

What made this vaccine work? The answer lay in the biological kinship between cowpox and smallpox viruses. Both belonged to the orthopoxvirus genus, and exposure to the relatively mild cowpox virus trained the body’s immune system to recognize and combat smallpox.

Though Jenner lacked microscopes powerful enough to visualize viruses or a concept of antibodies, his empirical findings anticipated modern immunology. The vaccine introduced a non-lethal infection that primed immune defenses—a tonic against the scourge.

Early Reactions: Support, Doubt, and Controversy in the Medical Community

The response to Jenner’s discovery was mixed and at times contentious. While many physicians and scientists embraced the vaccine's promise, others remained wary or hostile to its adoption. Entrenched medical traditions and fears of the unknown slowed early acceptance.

The vaccine faced not only medical but also religious and social resistance. Accusations flew: some priests sermonized that vaccination was unnatural or impious. Nevertheless, the evidence was mounting, and advocates like Jenner tirelessly published and demonstrated results.

The Spread of Vaccination: From Gloucestershire to the World

Jenner's discovery exploded beyond the borders of Gloucestershire. Within a decade, vaccination programs spread throughout Britain, Europe, and across oceans to the New World and colonies. Medical societies and governments recognized the urgent imperative to combat smallpox.

Notable figures, including Napoleon Bonaparte, championed vaccination, contributing to mass inoculation drives. Jenner became a celebrated figure, honored internationally for an intervention that would become a pillar of public health.

The Human Toll: How Jenner’s Discovery Saved Millions

Smallpox claimed hundreds of millions of lives over centuries. The impact of Jenner’s vaccine was revolutionary: mortality plummeted in vaccinated populations, disfigurement and blindness declined, and whole communities found reprieve. Public health improved dramatically.

Children who otherwise would have perished grew into adulthood. The scarred visage of smallpox retreated, replaced gradually with new hope. The vaccine became the foundation for saving countless lives, a beacon where death once loomed.

Smallpox Eradication: A Victory Forged Over Centuries

It took more than Jenner’s initial test to defeat smallpox, but he set humanity on a course that would culminate in the World Health Organization’s declaration of eradication in 1980—the first disease eradicated by human endeavor.

Global vaccination campaigns sped the end of smallpox, a testament to the enduring power of Jenner’s smallpox vaccine test and the subsequent adoption of vaccination as a societal duty.

The Legacy of the Smallpox Vaccine: Foundations of Modern Immunology

Jenner’s success seeded the science of vaccines and immunology as we know it today. His empirical model of experimentation, documentation, and mass inoculation influenced generations of scientists.

The principle of vaccination became a guiding light in the development of vaccines against polio, measles, influenza, and more. Jenner’s innovation underscored the profound human capacity to harness nature against disease.

Ethical Reflections: Testing on Humans and Medical Progress

Today, the ethics surrounding Jenner’s pioneering tests raise poignant questions. Was it acceptable to experiment on a child? How did understanding of consent differ in the 18th century?

These debates contextualize the evolution of medical ethics, informed consent, and human subject protections. Jenner’s work sits at the intersection of necessity and morality, reminding us that progress often walks a delicate line.

Jenner’s Personal Struggles and Triumphs

Behind the breakthrough lay Jenner’s personal story: a man passionate, dedicated, and imperfect. His perseverance in face of criticism, his quiet dignity amid fame, and his ceaseless commitment reflect the human dimension of scientific discovery.

Jenner’s life was entwined with the fate of his discovery—marked by honor but also by the solitude of a visionary ahead of his time.

The Socio-Political Impact: Public Health, Trust, and Resistance

Vaccination reshaped the relationship between states and citizens. Public health policies took form, governments began orchestrating campaigns, and the concept of herd immunity emerged.

Yet distrust lingered. Anti-vaccination sentiments did not start in the 21st century; Jenner’s era saw protests, pamphlets, and resistance rooted in fear and misinformation. Understanding this past is crucial for addressing vaccination today.

Anecdotes from the Field: Stories of Vaccination’s Early Days

Stories abound: from rural villages where entire communities embraced Jenner’s method with relief, to urban centers where skepticism clung fiercely. Tales of healed children, healed families, and long lines outside vaccination centers illustrate the human face behind statistics.

One striking tale recounts a farmer who, after receiving Jenner’s vaccine, survived a dreadful outbreak that claimed his neighbors—testimony to the vaccine’s power.

Statistical Proof: Data and Demonstrations of Efficacy

Jenner’s detailed notes and experiments were some of the earliest examples of clinical trial data. He documented nearly perfect protection in vaccinated subjects, a remarkable outcome at a time when controlled experiments were rare.

Later statisticians would analyze morbidity and mortality data, confirming the vaccine’s efficacy and setting the stage for evidence-based medicine.

Beyond Smallpox: How Jenner’s Work Inspired Future Vaccines

The ripples of Jenner’s experiment spread widely. Louis Pasteur, in the 19th century, built upon vaccination principles to combat rabies and anthrax. The entire field of vaccinology owes its roots to the modest inoculation in Gloucestershire.

From this first test emerged a new era of preventive medicine, reshaping human longevity and health worldwide.

The Modern Perspective: Smallpox Eradication in the 20th Century

The final conquest of smallpox relied on mass vaccination campaigns, global cooperation, and surveillance. Launched in the mid-20th century, these efforts culminated in the eradication declaration—a victory unthinkable not long ago.

This modern achievement frames Jenner’s first test not just as a scientific milestone but as a foundational step in a global health movement.

Cultural Memory: How Jenner’s Vaccine Changed Society’s View of Disease

Before Jenner, disease was often seen as an inevitable curse or divine will. After the vaccine’s success, perspectives shifted toward human agency and science.

Vaccination became a symbol of progress and hope, reflected in literature, art, and politics. Jenner’s work inspired a cultural transformation toward trust in medicine, grounded in evidence and innovation.

Conclusion

The smallpox vaccine test in Gloucestershire on that fateful day in May 1796 was more than a medical experiment. It was a beacon of hope, a testament to human courage, ingenuity, and the unyielding drive to overcome disease. Edward Jenner’s pioneering act, carried out in a humble village on a young boy’s arm, opened the door to a new era in human health—a proof that science can indeed triumph over nature’s deadliest threats.

This legacy reminds us how courage and patience converge to change the world, teaching future generations that even in the face of fear and uncertainty, progress is possible. Smallpox is gone, but the story of its conquest remains a powerful narrative of humanity’s resilience.

FAQs

1. What exactly was the smallpox vaccine test conducted by Edward Jenner in 1796?

It was the first deliberate inoculation of a human with cowpox virus to induce protection against smallpox, performed on James Phipps, proving that cowpox conferred immunity without causing the deadly effects of smallpox.

2. Why was smallpox such a feared disease before Jenner’s vaccine?

Smallpox was highly contagious and deadly, with mortality rates around 30%. Survivors were often left scarred or blind, and epidemics decimated populations worldwide.

3. How did Jenner come up with the idea to use cowpox in vaccination?

Jenner observed that milkmaids who contracted cowpox did not catch smallpox, suggesting a protective effect. This folk knowledge inspired his scientific testing.

4. What were the main risks associated with Jenner’s first vaccine test?

There was uncertainty whether cowpox inoculation was safe and effective; exposing a child to infectious material could cause severe illness. Jenner risked clinical failure and social backlash.

5. How did the smallpox vaccine impact global health?

The vaccine drastically reduced smallpox cases worldwide, eventually enabling complete eradication in 1980, saving millions of lives and changing public health forever.

6. Was Jenner’s use of James Phipps ethically acceptable at the time?

Medical ethics were not as codified as today; while some saw it as risky, it was generally accepted in the context of pressing public health needs, though modern reflections highlight consent issues.

7. How did society react to Jenner’s discovery initially?

Reactions were mixed—while many welcomed it as a miracle, some were skeptical or fearful, and religious and cultural resistance persisted.

8. In what ways did Jenner’s work influence future vaccine development?

Jenner’s approach established principles of vaccination, experimentation, and immunity, inspiring figures like Pasteur and shaping modern immunology.