Table of Contents

- Gathering Storm over Lujiang: China in the Shadow of Collapse

- Bandits or Survivors? The Making of Rebellion in a Broken Commandery

- Zhang Liao Before Lujiang: From Obscure Officer to Hardened Veteran

- The Mandate in the Ruins: Why Lujiang Mattered in 206

- First Footsteps into a Ravaged Land: Zhang Liao Enters Lujiang

- Mapping the Enemy: Intelligence, Fear, and Rumor in the Countryside

- The Arts of Persuasion and Terror: Zhang Liao’s Strategy Takes Shape

- Fire in the Hills: The Opening Campaign against the Bandit Strongholds

- Between Sword and Surrender: Negotiations at the Edge of Annihilation

- The Long Road to Pacification: Rebuilding Authority after the Battles

- Lives in the Crossfire: Peasants, Women, and the Cost of Order

- From Bandits to Soldiers: Amnesty, Recruitment, and Social Alchemy

- Politics Behind the Front: Cao Cao, Sun Quan, and the Strategic Value of Peace

- Memory, Myth, and the Records: How Historians Framed the Lujiang Campaign

- Echoes in Popular Imagination: Romance, Theater, and the Shadow of Fiction

- Assessing Zhang Liao’s Legacy: Governance through Courage and Calculation

- Conclusion

- FAQs

- External Resource

- Internal Link

Article Summary: In the year 206, amid the collapse of the Later Han dynasty, the campaign known as the zhang liao bandit suppression in Lujiang Commandery emerged as a pivotal moment in the struggle to restore order in war-torn central China. This article traces how Zhang Liao, a talented yet still-rising officer under Cao Cao, confronted a landscape ravaged by famine, civil war, and roving bands that blurred the line between criminality and desperate survival. Moving through the political, military, and emotional terrain of Lujiang, it follows his march into a devastated countryside, his use of strategy, negotiation, and force, and his harsh but calculated blend of punishment and clemency. The narrative explores the social cost of pacification, the transformation of former bandits into disciplined soldiers, and the quiet heroism and suffering of ordinary peasants caught in the middle. It also examines how court historians and later storytellers turned the zhang liao bandit suppression into a moral tale of just war and benevolent authority. Across these intertwined threads, the article reveals a complicated figure—at once warrior, governor, and symbol of a new political order—whose success in Lujiang helped shape later campaigns of the Three Kingdoms era. Yet behind the victory, it asks what price was paid, and by whom, for a fragile peace won with steel and fear.

Gathering Storm over Lujiang: China in the Shadow of Collapse

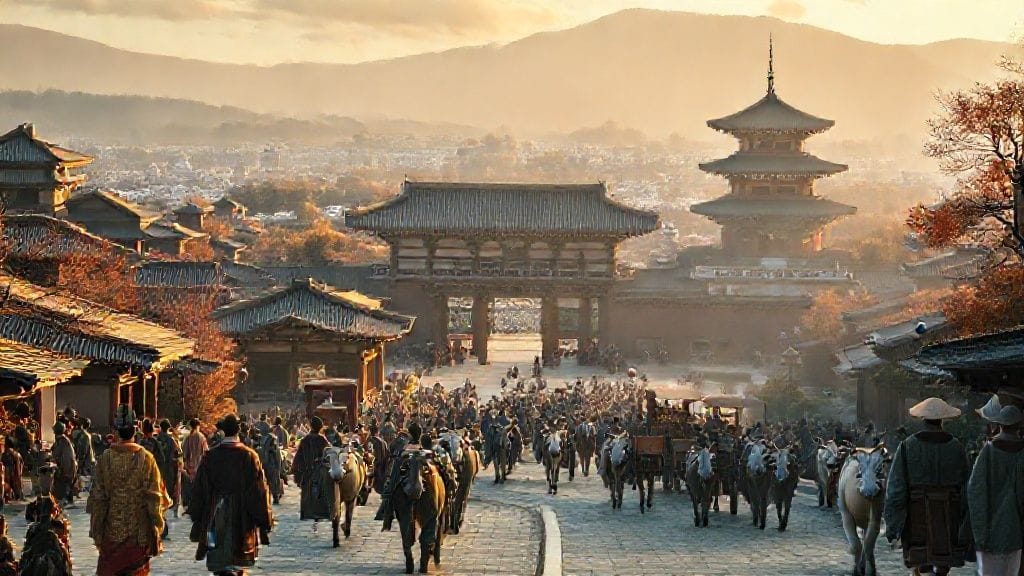

The story of Zhang Liao and his march into Lujiang Commandery in 206 unfolds against a China that had already passed its breaking point. The Later Han dynasty, once the lodestone of East Asian order, had been eaten hollow by decades of eunuch conspiracies, palace coups, and rural revolts. By the final years of the second century, it did not resemble the confident empire of earlier reigns; it looked instead like a slowly collapsing arch, every stone slipping just a little more each year.

Two events haunt the background like distant thunder. First, the Yellow Turban Rebellion of 184 shattered the illusion that the emperor could protect his people. Once-sedentary peasants rose in desperate waves, chanting for a “Great Peace” that never came, only brutal suppression and the scattering of armed survivors into hills and forests. Second, the warlord era that followed—marked by the rise of regional strongmen like Yuan Shao in the north and Sun Ce in the southeast—tore the imperial map into jagged pieces. In this fractured landscape, Lujiang Commandery, lying along the vital boundary between the Huai River basin and the lower Yangzi, became more than just an administrative unit; it was a contested frontier between rival visions of power.

By 206, the nominal emperor Xian still sat on the throne, but his authority was a thin veil stretched over the will of Cao Cao, the warlord who had seized control of the imperial court. Cao Cao presented himself as the protector of the Han, issuing edicts in the emperor’s name as he fought rival coalitions. Yet away from the corridors of Xu’s court, in places like Lujiang, imperial proclamations meant little. What mattered were harvests, taxes, and whether men with weapons would appear over the next hill.

Across the countryside, displaced people drifted in loose waves, their households broken by conscription, banditry, or flight from battlefields that flickered across the map like brush fires. In this world, the term “bandit” concealed a mess of social realities: deserters, starving farmers, failed rebels, and opportunistic marauders all blended into the same shapeless threat. When later texts describe the zhang liao bandit suppression in Lujiang, they often use the language of moral order versus chaos. But on the ground, the line between order and chaos was fuzzy, wet with rain and blood.

It is in this fragile landscape—riven by warlords, exhausted by rebellion, and covered with bands of the desperate—that Zhang Liao’s name enters the story. His campaign in Lujiang would not only test his military acumen but also the capacity of any man, however resolute, to impose stability on a land that had forgotten what peace felt like.

Bandits or Survivors? The Making of Rebellion in a Broken Commandery

To understand why Lujiang Commandery became a center of unrest, it is necessary to unravel how a region slides from imperial routine into endemic violence. Lujiang, positioned along the lower reaches of the Huai River and stretching toward the Yangzi basin, was once a fertile, thoroughly integrated part of the Han bureaucracy, studded with market towns and irrigated fields. Under stable conditions, its granaries fed soldiers and civilians far beyond its borders.

Those stable conditions had vanished. Years of war had disjointed the basic rhythms of agricultural life. Draft levies pulled adult men from the fields to serve in faraway campaigns; some never returned, while others came back as hardened veterans who found their land confiscated or ruined. Floods and droughts, ever the specters of premodern farming, struck with new ferocity when no coherent authority remained to coordinate relief.

Officials were supposed to manage this chaos, but officials were human too. Some fled when armies approached. Others enriched themselves on emergency taxes, turning grain meant for relief into private wealth. Still others simply lost the ability to enforce their will beyond the walls of their walled towns. In the gaps between failed administration and raw survival, small groups took up arms. They raided storehouses, attacked local convoys, and ambushed tax caravans. At first, these might have been episodic acts of desperation, but by 206, they had hardened into bandit formations with leaders, scouts, and regional influence.

To call these people merely “bandits” is to accept the language of the center, the view of men like Cao Cao who needed enemies to justify their wars of consolidation. Yet the truth is more disturbing. Many so-called bandits were dislocated farmers whose local ties had been severed. Their violence grew from profound social fracture, not from innate criminality. When later court histories such as Sanguozhi (“Records of the Three Kingdoms”) describe these groups, they often emphasize their cruelty—burned villages, slaughtered officials—but they also, occasionally, hint at their grievances: unpaid soldiers, unavenged injustices, or villages left to starve.

By the time Cao Cao turned his attention to the region, Lujiang had become a patchwork of fortified hamlets and roving bands. Local magistrates held barely more influence than the strongest gang chiefs. Grain convoys had to travel with armed escorts, and unguarded travelers simply vanished on lonely roads. It was in this setting that the zhang liao bandit suppression campaign would unfold—not as a clean, one-sided sweep, but as a grim negotiation with a landscape where the empire’s official maps had ceased to match reality.

Zhang Liao Before Lujiang: From Obscure Officer to Hardened Veteran

When the chronicles first introduce Zhang Liao, he is not yet the legendary general immortalized in later tales, but a man of modest birth fighting to stay afloat in an unsteady world. Born in Mayi (in modern Shanxi), he grew up close to the frontier, a hard land where the distinctions between farmer, soldier, and raider were thinner than they appeared in the capital’s records. This background mattered. On the frontier, children learned early that the failure of authority could be fatal, and that survival often depended on swift decisions and a firm hand.

As the Han order faltered, Zhang Liao served under various masters, including the powerful Lü Bu, shifting from one overlord to another as warlords rose and fell. These changes did not necessarily reflect disloyalty; they reflected an era in which loyalty itself was constantly renegotiated. It was under Cao Cao, however, that Zhang Liao’s talents caught sustained attention. After Cao Cao defeated Lü Bu at Xiapi, he absorbed many of Lü Bu’s surviving officers. Among them, Zhang Liao stood out for both courage and discipline.

Before being dispatched toward Lujiang, Zhang Liao had already earned a reputation in several campaigns along the central plains. He was known for leading from the front, rallying troops in desperate moments, and maintaining order in his ranks even amid chaotic engagements. Importantly, he also showed an aptitude for dealing with surrendered enemies. Where some officers resorted to indiscriminate slaughter, he had a habit—at least in the recollection of friendly sources—of combining severity with pragmatic leniency, accepting new recruits and reshaping them into effective units.

By 206, Cao Cao needed such men desperately. His larger strategy involved not only defeating rival warlords but also knitting together a fractured social fabric. The zhang liao bandit suppression operation in Lujiang would test more than Zhang Liao’s skill on the battlefield; it would probe his ability to transform enemies into subjects. The very traits that would later make him famous for his defense of Hefei—resolute bravery, strategic patience, and a capacity to inspire terror and admiration in equal measure—were already present as he rode southward toward a land that scarcely remembered the routine of imperial peace.

The Mandate in the Ruins: Why Lujiang Mattered in 206

If Lujiang Commandery had been just another troubled province, it might have been left to languish in semi-anarchy. But geography turned it into a prize. Nestled between the Huai River corridor and the rising power centers around the lower Yangzi, Lujiang was a hinge, a door that could swing open toward either Cao Cao in the north or the emerging Sun clan regime in the southeast. Whoever could pacify and hold Lujiang would possess a forward base for projecting influence; whoever lost it would find their flank exposed.

For Cao Cao, fresh from consolidating the north and advancing his claims as protector of the Han court, the persistence of bandit regimes in Lujiang was intolerable on several levels. Politically, lawless pockets undermined his narrative as the restorer of order. Economically, the disruptions in Lujiang menaced trade routes and choked the supply of grain and tax revenues. Strategically, they offered convenient allies or hiding places for his rivals, especially the forces aligned under Sun Quan, who was beginning to stabilize his power in the lower Yangzi following the campaigns of his elder brother Sun Ce.

Thus, the decision to send Zhang Liao to Lujiang was not merely a routine anti-bandit operation; it was a deliberate effort to demonstrate that Cao Cao’s authority could penetrate the most troubled corners of the realm. Success would transform Lujiang from a scar on the map into a banner of legitimacy. Failure would whisper that Cao Cao’s reach was shorter than his proclamations suggested.

Imperial documents, drafted in the name of Emperor Xian but guided by Cao Cao’s hand, framed the mission as the reestablishment of rightful governance. Local officials in adjacent commanderies were ordered to coordinate with Zhang Liao, to supply him with grain, and to recognize his authority in matters of pacification. Yet paper commands could only go so far. The men who actually rode under Zhang Liao’s banners had their own concerns: pay, loot, survival, and the hope—often fragile—that pacifying Lujiang might bring a measure of stability to their own wandering lives.

Behind the lofty rhetoric of restoring the Han, therefore, stood a simpler reality: a column of weary soldiers, horses clopping through fields scarred by neglect, officers hunched over rough maps, and scouts scanning the horizon for smoke from bandit camps. The zhang liao bandit suppression would be waged not in the halls of power, but in ravines, market streets, and damp rice paddies where imperial authority had become a rumor.

First Footsteps into a Ravaged Land: Zhang Liao Enters Lujiang

When Zhang Liao’s vanguard crossed into Lujiang’s administrative borders, they did not find a single, unified enemy waiting in neat formation. Instead, they encountered a landscape that seemed almost to shrink away from them. Villages were half-abandoned, their thatched roofs sagging and their wells fouled or choked with debris. Fields lay in uneven stages of neglect: some freshly burned from deliberate scorched-earth tactics, others overgrown with wild grass. At crossroads, signposts were hacked down, replaced by hastily carved markers pointing toward bandit strongholds or safe passes.

The army’s arrival was greeted less with open resistance than with silence. Doors remained barred; dogs barked without owners stepping outside. Peasants watched from the tree line, ready to vanish at the first sign that these new armed men were no better than the last ones. Zhang Liao’s first challenge was not to defeat a visible enemy, but to drag the contours of conflict out into the open.

He began with ritual and symbol, tools as important as spears. Proclamations were nailed to the gates of walled towns and posted at market squares—where markets still functioned. These edicts announced that anyone who had taken up arms in violation of the law but now surrendered would receive leniency. At the same time, they promised severe punishment for those who continued to prey upon the people. This dual promise formed the backbone of the zhang liao bandit suppression policy: mercy and terror, written in the same characters.

To give these promises weight, Zhang Liao needed visible acts. He ordered his officers to refrain from pillaging and executed several soldiers caught extorting villagers. These executions were public and deliberately theatrical. The message was intended for three audiences at once: local civilians, who needed to see that a different kind of authority had arrived; his own men, who had to learn that indiscipline would not be tolerated; and the bandits watching from the hills, who were meant to see that this was not just another warlord’s army seeking plunder.

Slowly, information began to flow. A herdsman guided scouts to a river ford where bandits had been seen crossing. A frightened innkeeper whispered the name of a local strongman who controlled a cluster of hamlets. A surrendered minor outlaw, spared death but forced to watch an execution up close, sketched crude maps of forest paths and hidden stockpiles. The contours of Lujiang’s crisis started to acquire shape in Zhang Liao’s mind. The campaign would not be a single decisive battle, but an unspooling sequence of raids, sieges, and tense negotiations, each one chipping away at the bandit networks that had become the region’s dark skeleton.

Mapping the Enemy: Intelligence, Fear, and Rumor in the Countryside

In a time before aerial scouts or telegraphs, information in Lujiang traveled on tired feet and nervous tongues. Zhang Liao understood that his greatest resource was not only the strength of his soldiers but also the knowledge locked inside terrified villagers and resentful minor chiefs. The zhang liao bandit suppression campaign thus became, from the outset, a battle for intelligence.

His officers spread through nearby settlements, not as marauding occupiers but as stern questioners. They called in village elders, scribes, and petty functionaries who had once reported to the now-limp Han bureaucracy. Under questioning, some spoke eagerly, hoping collaboration would earn protection. Others hesitated, haunted by past betrayals—what if the bandits returned and found their names on the lips of enemy messengers?

To break this paralysis, Zhang Liao resorted to a calculated pattern of incentives and visible consequences. Villages that cooperated received official seals promising reduced levies and temporary grain relief. Those that clearly sheltered bandits or supplied false information were made examples of, their leaders flogged or, in the most defiant cases, executed. These were cruel measures, yet they formed part of a grim arithmetic: each act of decisive punishment was meant to prevent longer cycles of violence.

Rumor, always slippery, became both hazard and tool. Stories circulated that Zhang Liao accepted entire bandit companies into his army if they surrendered early; other tales insisted he killed every captured leader and crucified them at crossroads. The truth lay somewhere between. He did execute certain chieftains whose crimes were particularly notorious, especially those who had massacred officials or claimed royal-sounding titles. But for lesser figures, he often chose pragmatic incorporation, enlisting their men into newly organized units after disarming and regrouping them under trusted officers.

Academic historians, drawing on works like Rafe de Crespigny’s prosopographical studies of the period, have noted how commanders like Zhang Liao relied deeply on local elites—not just gentry but also former rebels—to build a network of control that mirrored the empire’s old structures in rougher form. In Lujiang, this meant taking stock of who could be turned, who could be trusted, and who had to be destroyed. Every captured or surrendered bandit was a potential informant, but also a potential traitor. The campaign evolved into an intricate dance of promises and threats, with Zhang Liao at the center, trying to read faces and foresee betrayals before they took shape.

It is astonishing, isn’t it, how much of this war was fought in whispered conversations rather than on open battlefields? Yet without those whispers, no army, however disciplined, could have found its way through the thickets of fear and loyalty that held Lujiang in thrall.

The Arts of Persuasion and Terror: Zhang Liao’s Strategy Takes Shape

From these early encounters, Zhang Liao fashioned a strategy that blended moral theater with ruthless calculation. The zhang liao bandit suppression campaign hinged on three intertwined approaches: targeted annihilation of the most dangerous factions, staged clemency for those willing to submit, and a visible reconstruction of basic order in areas brought under control.

First, he identified the most powerful and ideologically dangerous bandit leaders—those who had adopted grandiose titles such as “General of the Righteous” or “King of the Huai Marshes.” Such men were more than thieves; they were potential nodes of political resistance, capable of aligning with Cao Cao’s rivals or even claiming to champion the common people against all warlords. Against these, Zhang Liao refused to compromise. He planned operations meant not only to kill them but to obliterate their reputations, leaving behind warnings rather than martyrs.

Second, he broadcast the possibility of surrender with ever-increasing clarity. Messengers were sent to minor strongholds with written guarantees of life in exchange for prompt obedience. Recalcitrant groups were given timetables—days or weeks—to come down from their hill forts and lay down arms. When some complied, he staged their submission as public events. Before assembled villagers and soldiers, leaders knelt, offered up their weapons, and received ritual pardons. Their followers, disarmed and counted, were either sent home or reorganized into closely supervised labor or militia units.

Third, Zhang Liao began to restore small but crucial elements of civilian life in pacified pockets: reopening markets, securing irrigation ditches, and ordering the repair of roads and bridges. To the modern reader, such acts may seem minor, but to exhausted peasants they signaled that a pattern of normal life might return. Each functioning market town became, in effect, a propaganda post. “When Zhang Liao’s flags appear,” people whispered, “the killing lessens, the roads clear.”

Of course, this perception was never universal. Some saw only the executions and forced levies that accompanied his presence. Yet compared with earlier waves of looters and opportunistic warbands, Zhang Liao’s regime of order, harsh though it was, offered a structured predictability. Punishments followed a coherence that people could learn; rewards, though limited, were real. This, in many ways, was the essence of early state-making during the age of warlords: turning raw coercion into a system that could be anticipated, navigated, and even, at times, trusted.

Fire in the Hills: The Opening Campaign against the Bandit Strongholds

Eventually, the time for whispers and proclamations passed. Some bandit leaders, emboldened by years of near-impunity or distrustful of any promises from a distant court, refused to submit. They retreated deeper into the hills and marshes, fortifying rough palisades and turning natural features into defensive networks. It was against these strongholds that the zhang liao bandit suppression campaign revealed its fiercest edge.

One of the earliest major confrontations occurred near a wooded ridge that dominates local chronicles under various names—“Wolf Hill,” “Bandit’s Crest,” or simply “the Ridge.” There, a coalition of several outlaw groups had dug in, confident that the steep slopes and tangled undergrowth would hinder any large-scale assault. They had stockpiled captured arrows, grain, and livestock, and built lookout posts commanding the approaches.

Zhang Liao did not simply charge. He sent forward small detachments under cover of darkness to probe the defenses, counting torches, mapping sentry routes, and noting where the hillside trails widened enough for formed ranks. Then, at dawn, he advanced with a deliberately visible force, drums beating in steady rhythm. As the defenders rushed to man their walls and release volleys of arrows, they discovered—too late—that their rear trails had been quietly blocked and their water sources cut off. A simultaneous flanking maneuver, led by veterans who had fought in the rough terrain of the north, seized a secondary knoll and began raining fire-tipped missiles into the bandit camp.

The battle that followed was brutal and close-quarters. Eyewitness-style accounts describe men grappling in the underbrush, fighting with short blades when longer spears became entangled in branches. Some bandits tried to break through the encirclement, only to be driven back by disciplined shield walls. Others, panicking as their fortifications caught fire, threw down their weapons and begged for mercy.

Zhang Liao’s response was coldly measured. Chieftains whose atrocities were well-known—those who had burned villages wholesale or executed captured officials—were dragged before the assembled captives. One by one, they were condemned, their crimes read aloud by an officer, and then executed by beheading. Their heads were mounted on pikes overlooking the burnt remains of the camp. Lower-ranking fighters, however, were sorted: some were released after swearing oaths and dispersed back to their home districts, while others were made to join labor battalions working on road repair and fortification building.

This pattern repeated across Lujiang: encirclement, shock assault, selective executions, and structured mercy. Each victory chipped away at the remaining resistance, and each mound of ashes left behind served as a somber warning. Yet it would be a mistake to imagine total submission. In the wake of these assaults, smaller, more agile bands melted deeper into the countryside. They continued to haunt the night roads, reminding everyone that even a successful campaign could not erase the pressures that had given rise to banditry in the first place.

Between Sword and Surrender: Negotiations at the Edge of Annihilation

As the campaign progressed into its middle stages, Zhang Liao faced an increasingly delicate problem. The very success of his operations had driven many bandit groups into a corner. Those who remained were either the most committed or the most desperate. Annihilating them entirely would require time, manpower, and more bloodshed—resources that Cao Cao, always juggling fronts, could not afford to sink indefinitely into one commandery.

Thus, persuasion returned to the forefront, now sharpened by the memory of destroyed strongholds. Envoys rode under flags of truce to secondary leaders, men who had not yet stained themselves with atrocities so infamous that no forgiveness was politically possible. These envoys carried a clear ultimatum: surrender now and live under strict but tolerable supervision, or face the kind of crushing assault that had consumed “Wolf Hill” and its coalition.

One such negotiation centered on a leader known in some regional records as Zhao Fan, a former minor official who had turned to banditry after being accused—rightly or wrongly—of embezzlement by a corrupt superior. Zhao had gathered around him a following of similarly disillusioned retainers and villagers. His camp was disciplined, closer to a small army than a rabble. Zhang Liao immediately recognized the danger and the opportunity: left unchecked, Zhao Fan could align with more ambitious warlords; brought into the fold, he could stabilize an entire district.

The parley that followed took place in a cleared field between hills, watched anxiously by both sides’ archers. Accounts suggest that Zhang Liao rode forward in full armor but with his helm unstrapped, a sign of readiness but also vulnerability. Words were exchanged, grievances aired. Zhao Fan reportedly accused the Han court of abandoning its people and demanded guarantees that his men would not be scattered and starved if they surrendered.

Zhang Liao’s answer, as recorded in later retellings, was blunt: “The empire is broken because men of talent fight only for themselves. If you claim to care for the people, lay down your spear and come stand where judgment reaches you too.” It was, of course, a deeply political statement, one that positioned Zhao Fan’s concerns within Cao Cao’s broader claim to be rebuilding a just order. Yet it also acknowledged, however theatrically, the moral ambiguity of the age.

In the end, Zhao Fan surrendered. His officers disarmed, their banners were lowered, and they marched into Zhang Liao’s camp to be registered and evaluated. Some were later integrated into garrison units, others sent back to administer their home villages under watchful eyes. The incident became a template for further surrenders, reinforcing the dual message at the heart of the zhang liao bandit suppression effort: resistance invited annihilation; submission, though humiliating, could be survivable.

But behind the scenes, not all negotiations ended so cleanly. Some leaders feigned surrender only to slip away in the night, taking advantage of any leniency. Others split their forces, sending decoy groups to yield while they maintained hard-core followers in hidden ravines. Every time such a betrayal occurred, Zhang Liao’s willingness to offer mercy was tested. Yet he persisted in the same balancing act, convinced—as many state-builders before and after him—that a peace built solely on corpses would collapse as soon as his army marched away.

The Long Road to Pacification: Rebuilding Authority after the Battles

Military victories alone could not secure Lujiang. Once the major bandit concentrations were broken and the most dangerous leaders dead or co-opted, Zhang Liao faced the slower, in some ways more daunting task of stitching together a functioning commandery administration. This work, often overshadowed in martial narratives, was the true test of whether the zhang liao bandit suppression campaign had achieved its purpose.

First came the reconstitution of local offices. Many magistrate positions stood empty, their previous occupants killed, fled, or too compromised to be trusted. Zhang Liao, acting under Cao Cao’s appointment powers, recommended new candidates—some drawn from surviving gentry families, others promoted from scribes or even reformed bandit officers who demonstrated administrative skill. It was a gamble; any new official could prove corrupt or disloyal. But an empty post, he knew, was worse than a risky appointee. Without someone to gather taxes, organize corvée labor, and handle disputes, the old vacuum would return.

Next came the question of taxation and relief. Fields lay in varying states of ruin. In some districts, wartime neglect had allowed weeds to choke irrigation ditches; in others, repeated raiding had left farm tools broken or stolen. Zhang Liao recommended temporary tax remissions for the hardest-hit areas, hoping to encourage planting rather than flight. Grain captured from bandit storehouses was redistributed in carefully measured quantities—enough to bridge immediate hunger, not so much as to foster dependency or attract thieves.

Roads and river crossings, vital for both commerce and control, were prioritized. Under armed supervision, mixed groups of soldiers, conscripted peasants, and former bandits repaired bridges, cleared fallen trees, and rebuilt modest ferries. Each restored route was both a symbol and a practical instrument of renewed authority. When merchants began to move cautiously again—leading donkeys, pushing carts, plying river junks—the murmur of small trade returned to the soundscape of Lujiang.

Yet danger remained. Low-level predation did not vanish; it merely changed form. Petty theft, small ambushes, and localized extortion persisted at the margins, reminding everyone that the peace was thin. Zhang Liao responded by stationing small garrisons at strategic points: town gates, ferry landings, grain depots. These garrisons, typically led by officers he had personally vetted, carried the dual responsibility of defense and deterrence. Their presence deterred most would-be raiders, though it could not erase hardship.

In letters back to Cao Cao’s court, which later historians paraphrase, Zhang Liao emphasized both progress and fragility. Lujiang, he argued, was on a path toward stability, but it needed time and continued support to consolidate its fragile gains. In a China where fronts shifted constantly, time was a luxury rarely granted. The measure of his achievement lies in the fact that, for a while at least, Lujiang did not relapse into full-scale rebellion once his army shifted to new assignments.

Lives in the Crossfire: Peasants, Women, and the Cost of Order

Statistics of pacification—numbers of bandits killed, surrendered, resettled—tell only part of the story. Beneath those numbers lay countless lives bent or broken by the violence that had wracked Lujiang long before Zhang Liao arrived. To see the full human dimensions of the zhang liao bandit suppression, one must shift the gaze from general to villager, from battlefield to household.

Consider the peasants who had weathered successive storms: first the levy collectors, then the warbands, then the bandits, and finally Zhang Liao’s disciplined but hungry troops. For them, each new column of armed men meant risk. Even a well-ordered army demanded supplies. Even principled officers were tempted to requisition more than they could pay for. Some villages, crippled by repeated “emergency contributions,” simply lacked enough grain to survive the next winter. For families already on the edge, the arrival of Zhang Liao’s forces did not feel like liberation; it felt like yet another set of mouths to feed under duress.

Women bore their own share of burdens. Bandits and soldiers alike could become predators. Rape, forced marriages, and the sale of women and children as slaves or concubines formed a cruel undercurrent to the official narrative of conquest and pacification. Sources tend to fall silent here, constrained by the moral language of their time and by the priorities of male chroniclers. Yet in the margins of accounts, one sees traces: references to “restoring kidnapped families,” to “recovering abducted women,” or to “punishing those who violated the sanctity of households.” Each euphemism covers many unrecorded nights of terror.

When Zhang Liao enforced strict discipline on his soldiers—executing plunderers, outlawing unauthorized seizures—he was not only securing order for its own sake; he was also, however imperfectly, trying to curb this tide of abuse. To the extent that he succeeded, women and children in pacified zones gained a measure of safety. But no system could rewind time for those already harmed. The scars of the bandit years remained visible in broken families, missing relatives, and fields now tended by widows and orphans.

There were, too, the ambiguous figures: peasants who had joined bandit bands out of desperation and now faced the consequences of surrender or defeat. Some returned home, only to be eyed with suspicion by neighbors who wondered whether they might revert to robbery if crops failed again. Others were resettled in new districts, stripped of their old identities, forced to build new kinships from scratch.

The social world of Lujiang after 206 thus bore the imprint of both devastation and reconstruction. Every measure of stability Zhang Liao achieved rested upon sacrifices that many individuals had not chosen but had endured. Behind the relatively clean lines of military and administrative history lies a crowded canvas of private grief, modest hopes, and the slow, painful work of putting lives back together in the shadow of imperial politics.

From Bandits to Soldiers: Amnesty, Recruitment, and Social Alchemy

One of the most striking aspects of the zhang liao bandit suppression lies in what followed the battles: the deliberate, methodical transformation of former enemies into pillars of the new order. In an age short on manpower and long on conflicts, it was a luxury to kill every opponent. Cao Cao, like many pragmatic rulers, preferred to recycle human resources when possible. Zhang Liao became one of his most skilled practitioners of this harsh alchemy.

Amnesties were the gateway. After major surrenders, Zhang Liao’s staff compiled lists of captured men, noting their origins, prior occupations, and degree of involvement in known atrocities. Those judged less culpable were offered the chance to join new military units or to engage in corvée projects for a determined period in exchange for eventual freedom. It was hardly a gentle system, but compared to the alternative—mass execution—it offered a path, however narrow, back into legitimate society.

The new units were structured to dilute old loyalties. Former bandits were mixed with long-serving regular troops and placed under officers whose loyalty to Cao Cao was beyond doubt. Training emphasized not only drill but also discipline, with repeated warnings about the consequences of desertion or relapse into robbery. Some accounts suggest that Zhang Liao personally inspected these formations, speaking to them not just as prisoners but as potential comrades-in-arms. In doing so, he tried to reshape their sense of identity—from outlaws seeing the state as an enemy to soldiers seeing themselves as instruments of a renewed order.

Such social transmutation did not always succeed. There were desertions, mutinies, and quiet defections back into the hills. Yet enough men stayed that the balance of power in Lujiang shifted decisively. In later campaigns under Cao Cao and afterwards, veterans originally drawn from Lujiang’s bandit ranks fought as regular troops, their origins blurred by time and by the anonymity of military hierarchies.

Historians like Mark Edward Lewis, analyzing similar patterns across the late Han and early Three Kingdoms, have emphasized how the line between “bandit” and “soldier” was often a matter of context rather than essential nature. Zhang Liao’s efforts in Lujiang exemplify this reality. With the right combination of sticks and carrots—threat of execution, promise of survival, and the stability of regular pay—men who had once robbed travelers along forest paths marched instead in organized ranks under imperial banners.

This process, however, did not merely flip a moral switch. It carried risks. Integrating large numbers of former outlaws into the army could import bandit habits into the very institution meant to suppress them. That is why Zhang Liao’s stress on discipline and visible justice mattered so much. His reputation for strict fairness, burnished during the campaign, became a key ingredient in making these fragile new units function. Where a weaker commander might have lost control, he managed, at least for a crucial span of years, to harness violent energies instead of merely scattering them.

Politics Behind the Front: Cao Cao, Sun Quan, and the Strategic Value of Peace

While Zhang Liao labored in Lujiang, the broader chessboard of Chinese politics continued to shift. Far to the north, Cao Cao maneuvered against residual threats from Yuan Shao’s fractured coalition. To the southeast, Sun Quan consolidated power along the lower Yangzi, building on the territorial foundation laid by his brother Sun Ce. In this volatile environment, Lujiang was more than a troubled backwater; it was a contested frontier whose fate could tip the balance between rival power blocs.

Cao Cao’s strategy, as reconstructed by modern scholars drawing on texts like Sanguozhi and Pei Songzhi’s commentary, combined relentless military campaigns with a keen eye for legitimacy. He framed his moves as efforts to “rescue” the emperor and “restore” the Han, using these moral claims to justify both harsh internal measures and expansionist campaigns. The successful zhang liao bandit suppression fed directly into this narrative. Each pacified commandery, each restored tax registry, could be presented as proof that he, not his rivals, was the true guardian of civilization.

Sun Quan and his advisers were not blind to these dynamics. Lujiang lay adjacent to regions Sun’s forces hoped to influence or one day absorb. An unpacified Lujiang, full of bandit refuges, posed both threat and opportunity: threat, because uncontrolled brigands could raid into Sun’s territories; opportunity, because dissatisfied groups might be encouraged to ally with the southeast regime against Cao Cao. Once Zhang Liao’s campaign began to show results, that option narrowed. The more firmly Lujiang was tied into Cao Cao’s administrative system, the less room remained for Sun Quan to wield it as a bargaining chip.

This is why Zhang Liao’s later prominence as a commander stationed near the frontiers with Sun Quan’s domain—most famously at Hefei—makes historical sense. His success in Lujiang demonstrated not only tactical skill but also an ability to manage borderland societies where allegiance was fluid. He had proven he could handle hybrid threats: part military, part social, part political. For Cao Cao, such a man was invaluable at the edges where his authority frayed and rival powers pressed in.

Thus, while peasants in Lujiang might have experienced the campaign as a grinding struggle between bandit terror and military discipline, at the macro level it served as a move in a larger game. A stabilized Lujiang was a quieter southern flank for Cao Cao, freeing attention and troops for other theaters. It also denied Sun Quan a chaotic hinterland from which to draw proxies. In this way, the smoke rising from burned bandit camps in 206 formed faint but real lines in the strategic map that would culminate, only a few years later, in great clashes such as the Battle of Red Cliffs.

Memory, Myth, and the Records: How Historians Framed the Lujiang Campaign

Our understanding of Zhang Liao’s campaign in Lujiang is mediated through layers of narrative, each shaped by its own political and moral agendas. The earliest substantive accounts appear in Chen Shou’s third-century Sanguozhi, compiled after the Three Kingdoms period had run its course. Chen wrote under the Western Jin dynasty, which had reunified much of China by conquering the states that traced their origins to Cao Cao, Sun Quan, and Liu Bei. His work sought not only to document but also to make sense of a generation of fragmentation.

In Sanguozhi, Zhang Liao emerges as one of Cao Cao’s most capable generals, praised for courage and intelligence. The Lujiang episode is treated as a key stepping stone in his career: a demonstration that he could handle complex operations, manage surrenders, and impose order in chaos. Yet Chen Shou does not dwell excessively on the human cost; his narrative voice is concise, focused on offices held and achievements counted. Only in later commentaries—most famously those by Pei Songzhi in the fifth century—do we find additional anecdotes and alternative accounts, some of which hint at rougher edges and contested interpretations.

Pei Songzhi, often cited in modern translations and studies, gathered additional material from now-lost works, inserting them as expansive notes. Through him, we hear occasional dissenting voices or elaborations on terse original entries. Some of these emphasize the ferocity of Zhang Liao’s campaigns; others highlight his fairness and capacity for clemency. The result is a composite image, half-statue, half-shadow.

Modern historians, consulting not only Sanguozhi but also administrative texts and comparative studies of bandit suppression, have tried to situate the Lujiang campaign within broader patterns of late Han statecraft. Works like Rafe de Crespigny’s A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (Brill) and Mark Edward Lewis’s The Early Chinese Empires (Harvard University Press) approach figures like Zhang Liao not as isolated heroes, but as functionaries in a larger process: the violent but creative reconfiguration of imperial structures under warlord rule.

In these treatments, the zhang liao bandit suppression is both an event and a case study. It illustrates how fractured authority was reassembled, how categories like “bandit,” “rebel,” and “official” could shift depending on who held power. It also serves as an example of how memory works: how later states and historians chose to remember such campaigns as stories of restoration rather than of conquest, emphasizing the virtues of men like Zhang Liao while softening the brutalities that ordinary people endured.

Echoes in Popular Imagination: Romance, Theater, and the Shadow of Fiction

While official histories laid the foundation for Zhang Liao’s reputation, it was later popular culture that burnished him into near-myth. The Ming-dynasty novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo Yanyi), attributed to Luo Guanzhong, turned the era’s tangled wars into a sweeping epic. There, Zhang Liao appears as a formidable general, most famously in episodes like the defense of Hefei, where he leads a daring sortie against Sun Quan’s forces. The Lujiang campaign, by contrast, slips toward the background, overshadowed by more theatrical set-piece battles.

This selective focus reflects the priorities of storytelling. Readers and theater audiences thrill to dramatic duels and bold cavalry charges; painstaking pacification work is harder to dramatize. Yet even in its relative absence, the logic of the zhang liao bandit suppression lingers in these tales. The Zhang Liao who strides out before Sun Quan’s army at Hefei, commanding both fear and respect, is the same man who once walked among the ruins of Lujiang’s villages, weighing life and death for kneeling bandit chiefs.

Local operas and storytelling traditions in some regions of Anhui and Jiangsu, where Lujiang’s historical footprint lies, occasionally preserve snippets of memory more closely tied to the bandit-suppression period. Ballads speak of “the general who hung thieves at the crossroads” or “the stern guest from the north who stayed the soldiers’ hands,” reflecting a complex mixture of fear and gratitude. In these songs, Zhang Liao can appear alternately as avenging demon and as proto-Confucian guardian of the peasants, a duality that speaks to the ambiguous experience of imperial rule in frontier zones.

Popular imagination also reshaped the bandits themselves. In some folk tales, particular chieftains become tragic heroes, men “forced” into rebellion by corrupt officials, who nonetheless meet their end under Zhang Liao’s relentless pursuit. These stories blur moral lines even further, inviting listeners to sympathize with both sides in different moments. In doing so, they preserve something of the raw emotional texture of Lujiang’s crisis: a world in which no one chose the era they were born into, but everyone had to choose, again and again, how to survive within it.

Thus, even where the specifics of the 206 campaign fade, its emotional imprint persists. Zhang Liao’s persona in fiction—a general at once fierce and strangely upright—owes much to how his actions in places like Lujiang were remembered, retold, and eventually woven into the long tapestry of Three Kingdoms legend.

Assessing Zhang Liao’s Legacy: Governance through Courage and Calculation

Looking back from a distance of nearly two millennia, it is tempting to flatten Zhang Liao into a single archetype: the loyal general, the iron disciplinarian, the brilliant tactician. Yet the Lujiang campaign, seen in full, resists such simplification. It reveals a man operating within, and sometimes pushing against, the constraints of a collapsing empire and a violently reorganizing political order.

On one level, the zhang liao bandit suppression stands as a clear military and administrative success. A region that had descended into chronic lawlessness was, within a few years, largely brought back under structured control. Major bandit formations were destroyed or converted, trade routes reopened, and basic official functions restored. From the perspective of Cao Cao’s state-building project, this was exactly the kind of outcome needed to transform provisional dominance into sustainable rule.

On another level, the campaign exposes the moral cost of such achievements. Executions, coerced labor, forced recruitment, and heavy-handed discipline were integral to Zhang Liao’s methods. Even his mercies—amnesties, leniency for lesser offenders—served strategic ends. Mercy was a tool, not an abstract virtue. Does this diminish his reputation? Or does it simply anchor him more firmly in the rough realities of his age, where any hope of wide-scale stability demanded hard, sometimes brutal choices?

Compared with some of his contemporaries, Zhang Liao stands out for the consistency of his discipline and the relative restraint of his troops. This is not to romanticize him, but to note differences in degree. In a world where armies often treated conquered regions as fair game, his insistence on punishing his own soldiers for unauthorized plunder mattered. It helped make his promises of protection credible to civilians and his offers of amnesty plausible to bandits. In this sense, Zhang Liao governed not only through fear but also through a reputational capital built on predictable enforcement of rules—harsh rules, but rules nonetheless.

His legacy in Lujiang also illustrates how individual agency intersected with structural forces. Without Zhang Liao’s particular combination of toughness and pragmatism, the campaign might have degenerated into an endless cycle of slaughter and rebellion. Yet no individual, however capable, could by themselves alter the deeper currents: population displacement, environmental stress, and the centrifugal pull of multiple warlord regimes. The partial, precarious peace he forged was as durable as the political order that sustained it—and that order itself would change, fragmenting into the full-blown Three Kingdoms period after Cao Cao’s death.

Still, when later historians and storytellers searched for figures who embodied the possibility of order in a time of chaos, Zhang Liao’s name returned again and again. The memory of his work in Lujiang, though often overshadowed by more glamorous battles, underpinned this reputation. In the smoky aftermath of burned bandit camps and the hesitant reopening of markets, one can glimpse the outlines of a legacy built not solely on brilliant charges but on the grim, necessary work of making a shattered society governable again.

Conclusion

The campaign in Lujiang Commandery in 206—a moment we now conveniently summarize as the zhang liao bandit suppression—was never simply a matter of “good general defeats bad bandits.” It was born from a world in free fall, where the authority of the Han had withered and millions navigated the dangerous space between loyalty and survival. Zhang Liao entered that world as an instrument of a new power, carrying Cao Cao’s mandate to restore order with both sword and statute.

Through a combination of targeted violence, calculated mercy, and administrative reconstruction, he succeeded in turning a region of chronic unrest into a functioning, if fragile, part of a reconstituted polity. Along the way, he reshaped lives: executing hardened offenders; offering lesser bandits a ladder back to legitimacy; imposing discipline on his own forces; and giving exhausted peasants, for a time, something like predictable governance. Yet every success carried a shadow. The peace he created was steeped in sacrifice, and it could not undo the years of suffering that had driven so many to the hills in the first place.

In the broader sweep of history, Lujiang’s pacification helped secure Cao Cao’s southern flank and contributed to the strategic configurations that would define the early Three Kingdoms. In the more intimate scale of memory, it fed into the image of Zhang Liao as a commander who mixed daring with integrity, inspiring both fear and respect. Later chronicles and novels, from Sanguozhi to Romance of the Three Kingdoms, reworked his story into various moral and dramatic shapes, but the core remained: here was a man who, in an age of chaos, managed, however imperfectly, to bend violence toward the creation of a new order.

To study his campaign in Lujiang is to confront uncomfortable truths about how states are built and maintained—truths that echo far beyond one commandery, one year, or one general’s career. Order and justice, we are reminded, have often emerged not from pristine ideals alone but from choices made in mud, smoke, and fear. Zhang Liao’s story does not absolve those choices, but it does make them legible, inviting us to look more closely at the human costs and fragile hopes that lie between the lines of even the most triumphant historical reports.

FAQs

- Who was Zhang Liao, and why is he significant?

Zhang Liao was a prominent general of the late Han and early Three Kingdoms period, most closely associated with the warlord Cao Cao. He is renowned for his military skill, strict discipline, and key roles in campaigns such as the pacification of Lujiang Commandery in 206 and the later defense of Hefei against Sun Quan’s forces. - What was the main goal of Zhang Liao’s campaign in Lujiang Commandery in 206?

The primary goal was to suppress widespread bandit activity that had turned Lujiang into a zone of chronic instability, threatening trade, taxation, and political control. By breaking, co-opting, or reorganizing bandit groups and restoring basic administration, Zhang Liao sought to reintegrate the commandery into Cao Cao’s growing realm. - Were the “bandits” in Lujiang simply criminals?

Not entirely. While some were predatory raiders, many were displaced peasants, deserters, or former rebels driven to armed resistance by war, famine, and administrative breakdown. The category “bandit” in this era covered a spectrum of social and political realities, from opportunistic thieves to quasi-military factions with local support. - How did Zhang Liao balance mercy and punishment during the campaign?

He pursued a dual strategy: executing or annihilating the most dangerous and notorious leaders while offering amnesty and incorporation to lesser participants who surrendered promptly. This approach used visible terror to deter resistance and carefully staged clemency to encourage defections and rebuild manpower. - What were the long-term effects of the Lujiang pacification?

In the short to medium term, Lujiang became more stable, with reopened trade routes, reconstituted local offices, and reduced large-scale banditry. Strategically, this bolstered Cao Cao’s southern frontier and limited opportunities for rival powers like Sun Quan. Socially, the region remained marked by loss and dislocation, but it gained a degree of predictable governance absent for years. - How do we know about the zhang liao bandit suppression campaign today?

Our main sources are early medieval Chinese histories, especially Chen Shou’s Sanguozhi and its later commentary by Pei Songzhi, supplemented by modern scholarly analysis. These texts, combined with comparative studies of late Han banditry and warlord rule, allow historians to reconstruct the outlines of the campaign and its broader significance. - Is Zhang Liao’s role in Lujiang portrayed in popular works like Romance of the Three Kingdoms?

Romance of the Three Kingdoms focuses more on Zhang Liao’s later exploits, particularly at Hefei, and gives relatively less narrative space to Lujiang. However, his characterization in the novel—as a brave, disciplined, and formidable general—is deeply informed by the reputation he built in campaigns like the pacification of Lujiang.